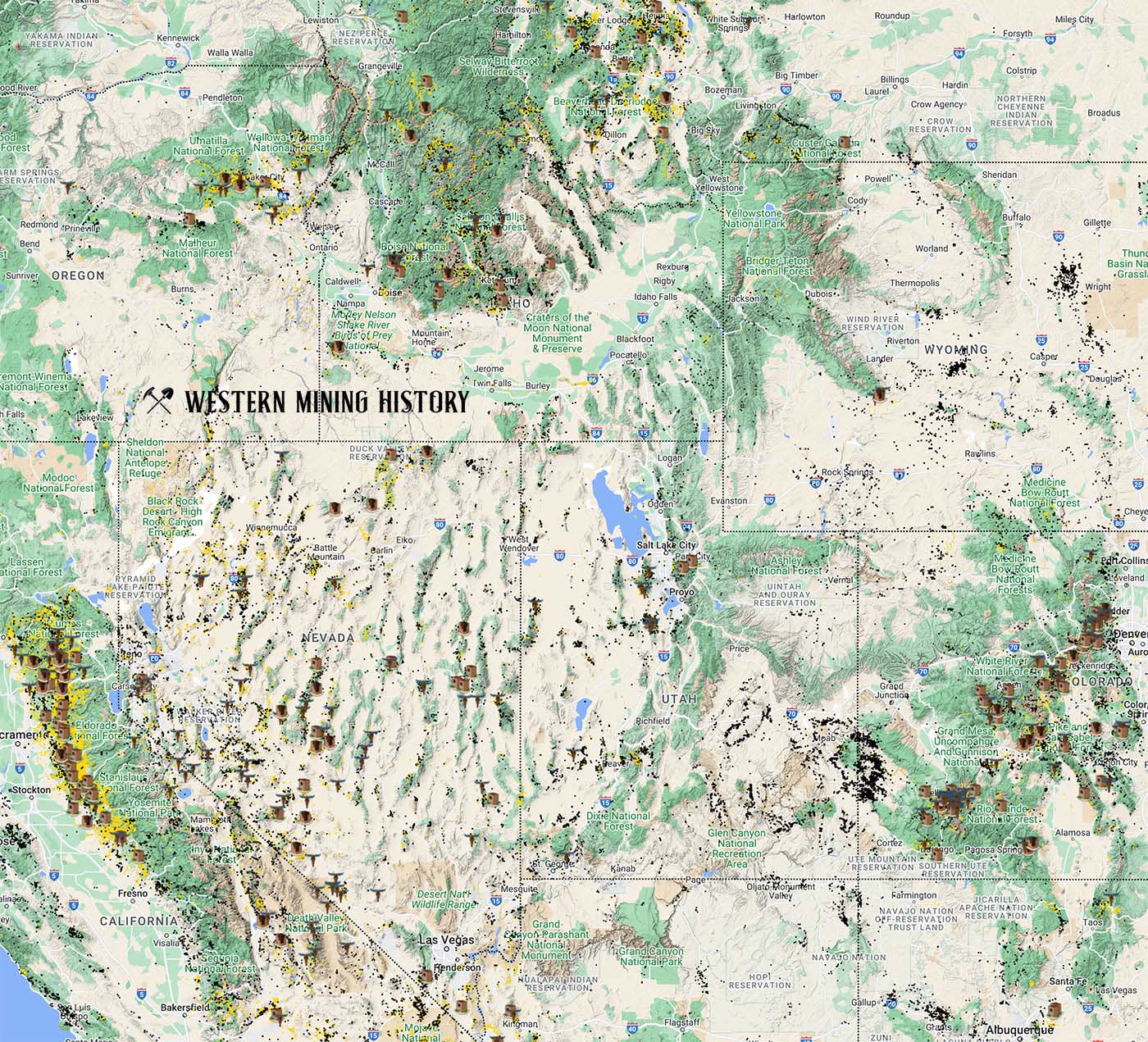

The image above illustrates the incredible scale of the mining regions of the western United States. Yellow dots are gold mines, black dots are non-gold mines. Map icons show the distribution of historic mining towns. An interactive version of this map is available here.

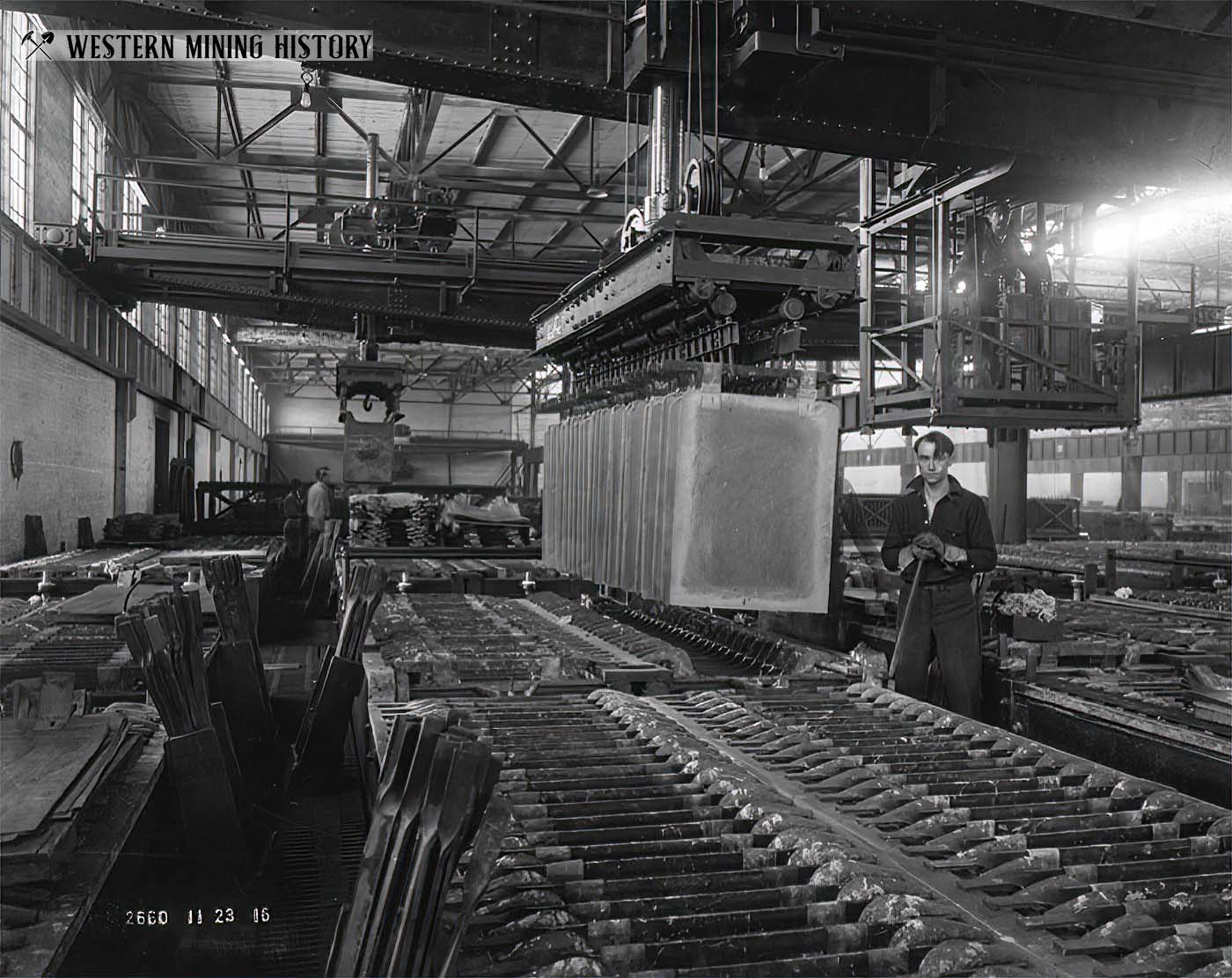

The Great Falls Reduction Department

Processing ore from the great mines of Butte, Montana required significant industrial capacity spread over a large area of the state. With over 30 photos, this article takes a detailed look at the massive facility known as the Great Falls Reduction Department, where copper and zinc were refined into finished products. Continue Reading

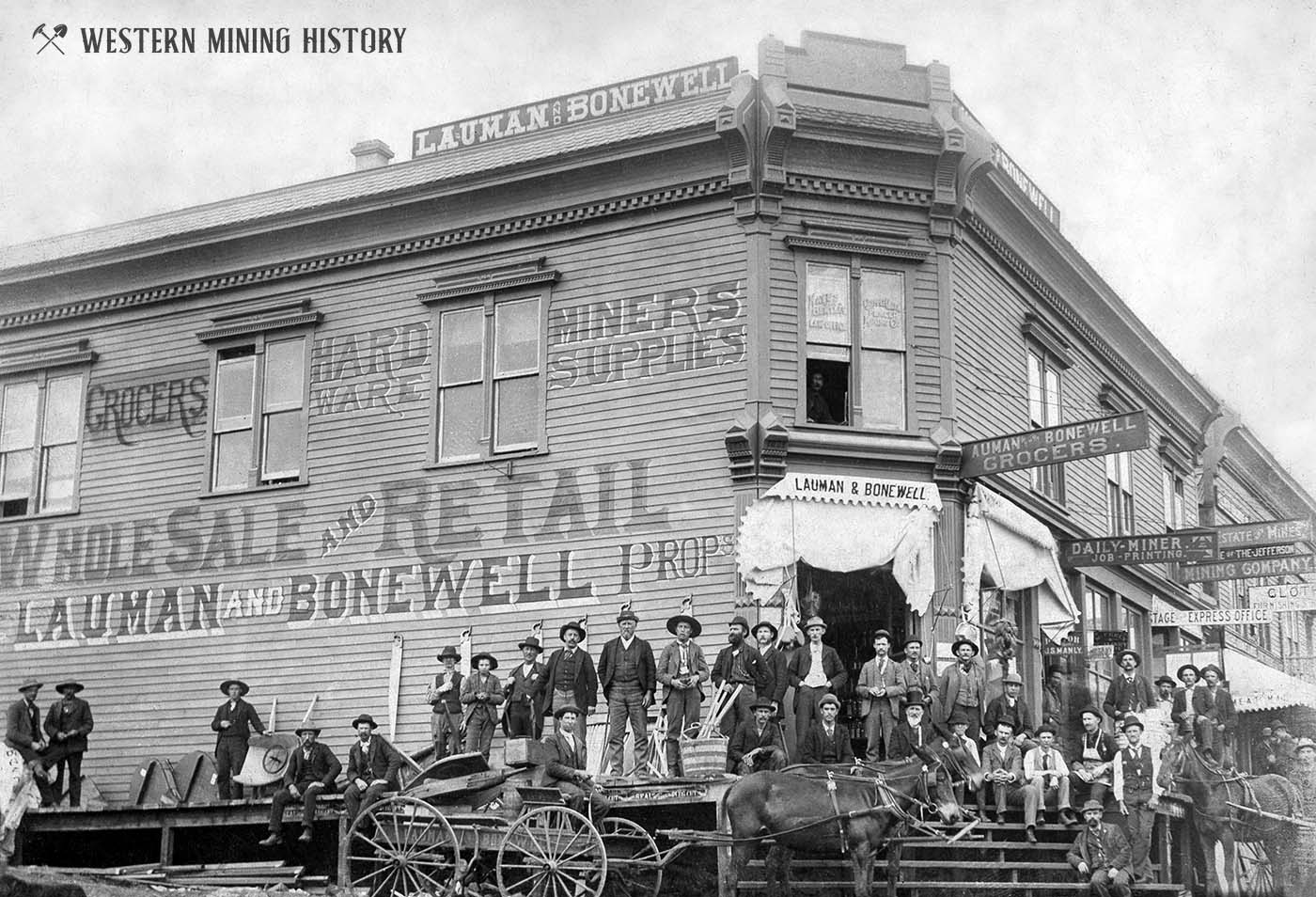

Bandits and Badmen: Crime in the Cripple Creek District

Within a few years of the 1890 gold discovery at Cripple Creek, the area had transformed into one of the world's fastest growing gold districts. Thieves, bandits and buncos were attracted to the towns of new district by the hundreds, and Cripple Creek became known for its lawlessness. Continue Reading

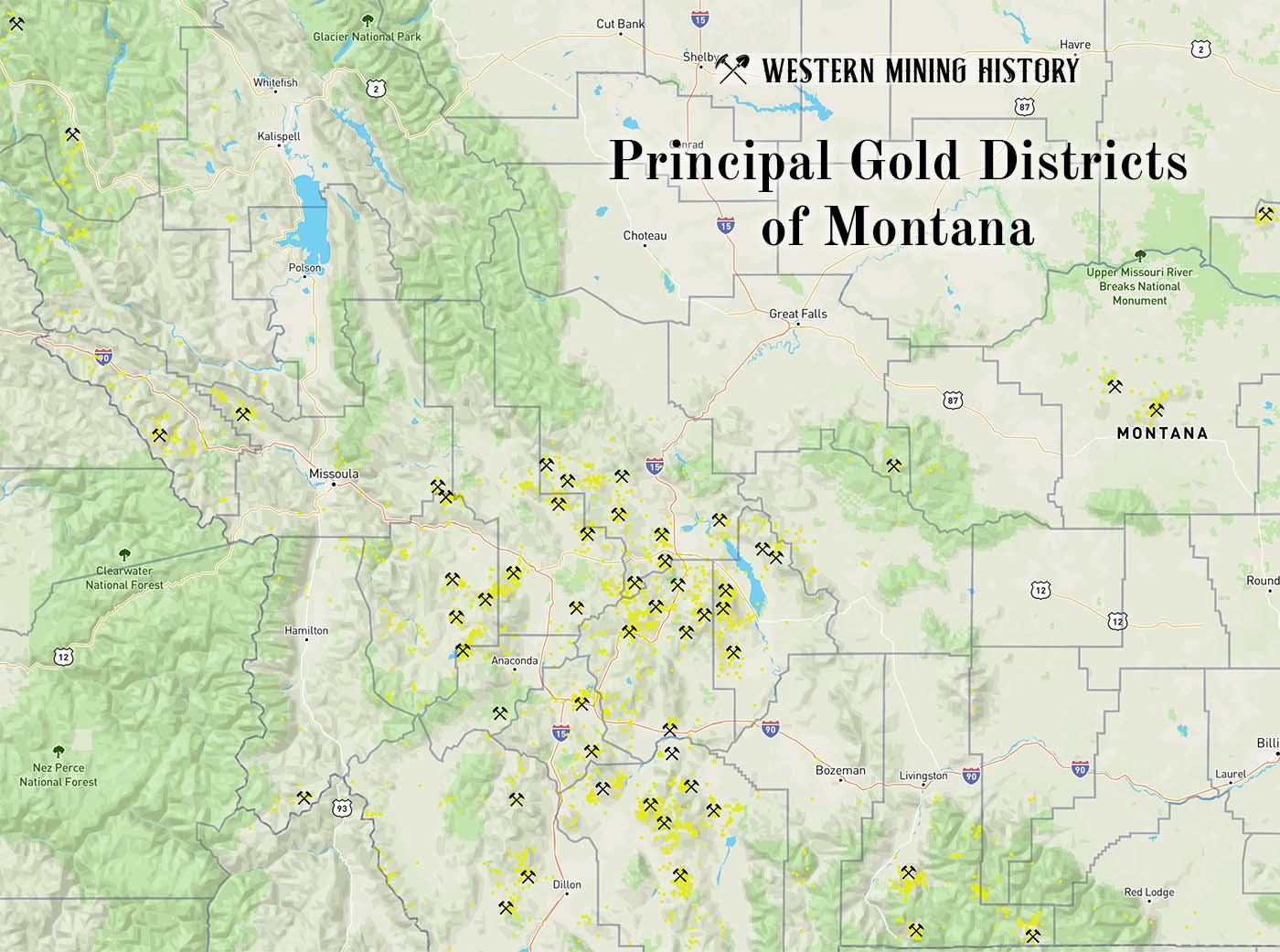

Principal Gold Districts of Montana

In Montana, 54 mining districts have each have produced more than 10,000 ounces of gold. The largest producers are Butte, Helena, Marysville, and Virginia City, each having produced more than one million ounces. Twenty seven other districts are each credited with between 100,000 and one million ounces of gold production. Continue Reading

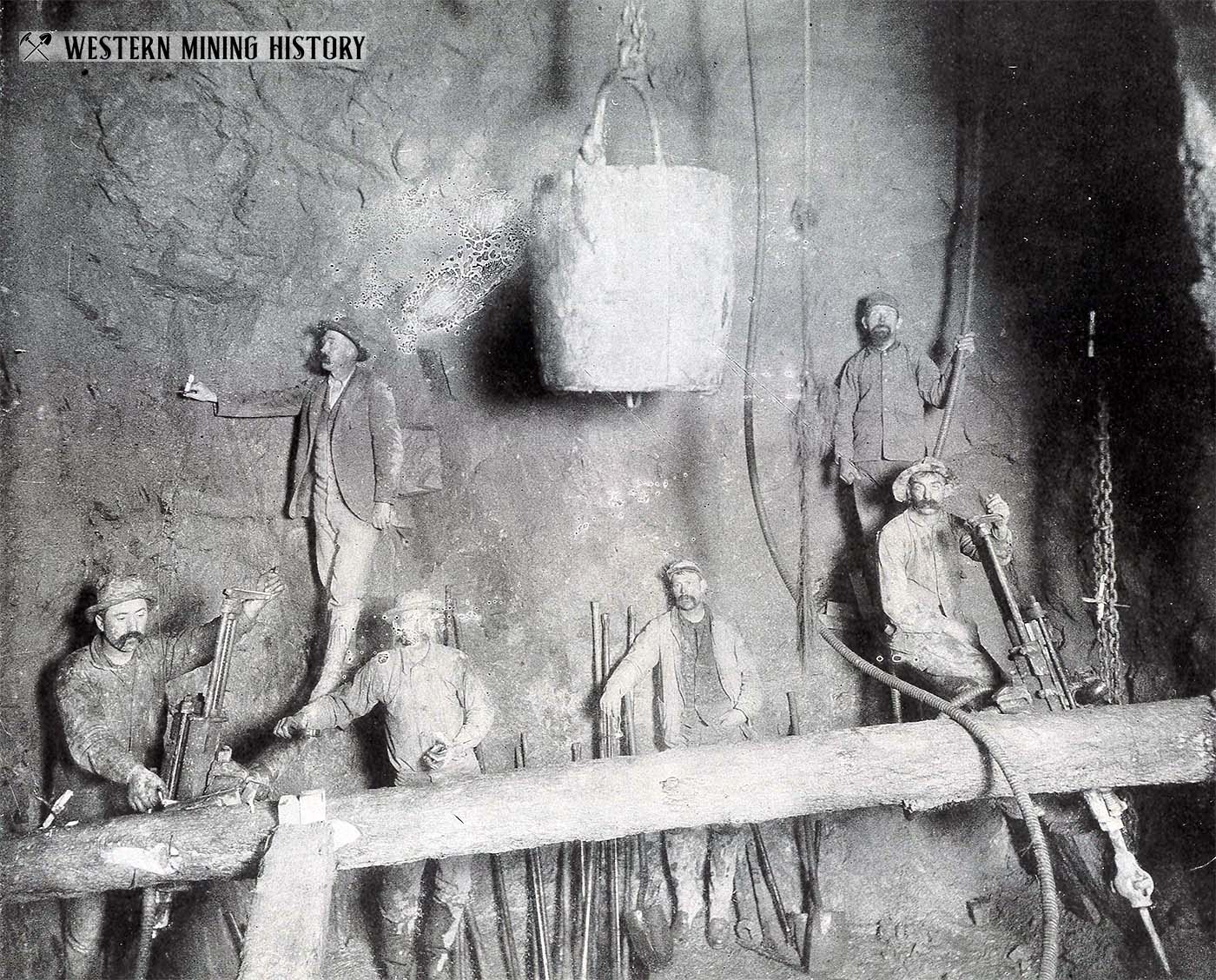

Gathering Gold: The Mines of Bobtail Hill

"Gathering Gold - An Illustrated Treatise on Modern Methods of Operating Gold Mines and Marketing Their Product" by General Frank Hall gives a fascinating look at the mines of Bobtail Hill at Blackhawk, Colorado around 1900. Continue Reading

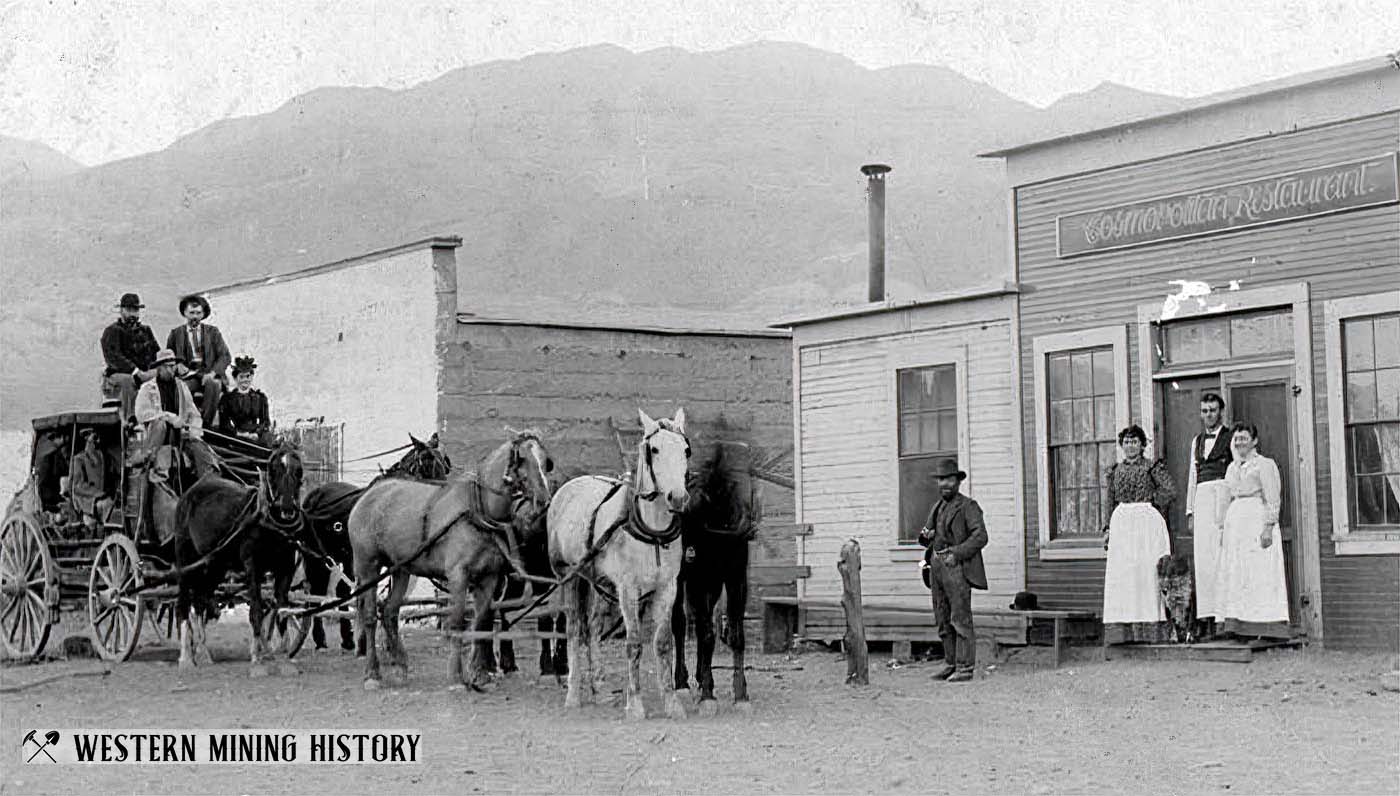

Featured Mining Town: Darwin, California

Darwin, California was the site of an important silver rush in the mid 1870s. The high grade surface ores were exhausted in a couple years and the district quickly declined, but eventually large scale mining of lower grade ore revived the town, which became the Death Valley region's most permanent settlement. Continue Reading

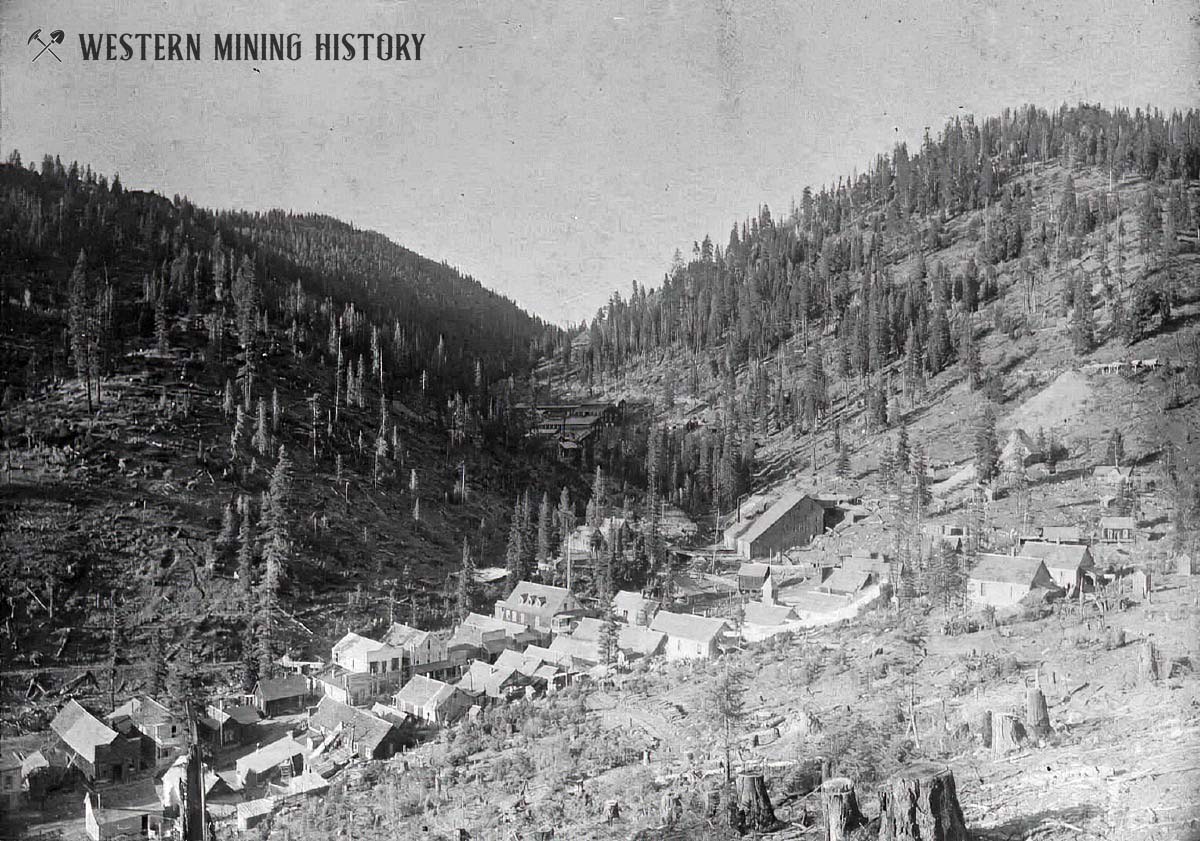

Featured Mining Town: Bourne, Oregon

Bourne, Oregon was settled in 1888 to support the rich gold mines that surrounded the town. During the 1890s this was a typical western mining town, however by 1905 Bourne became the center of an elaborate mining stock scheme that spanned a decade and bilked investors worldwide out of millions of dollars. Continue Reading

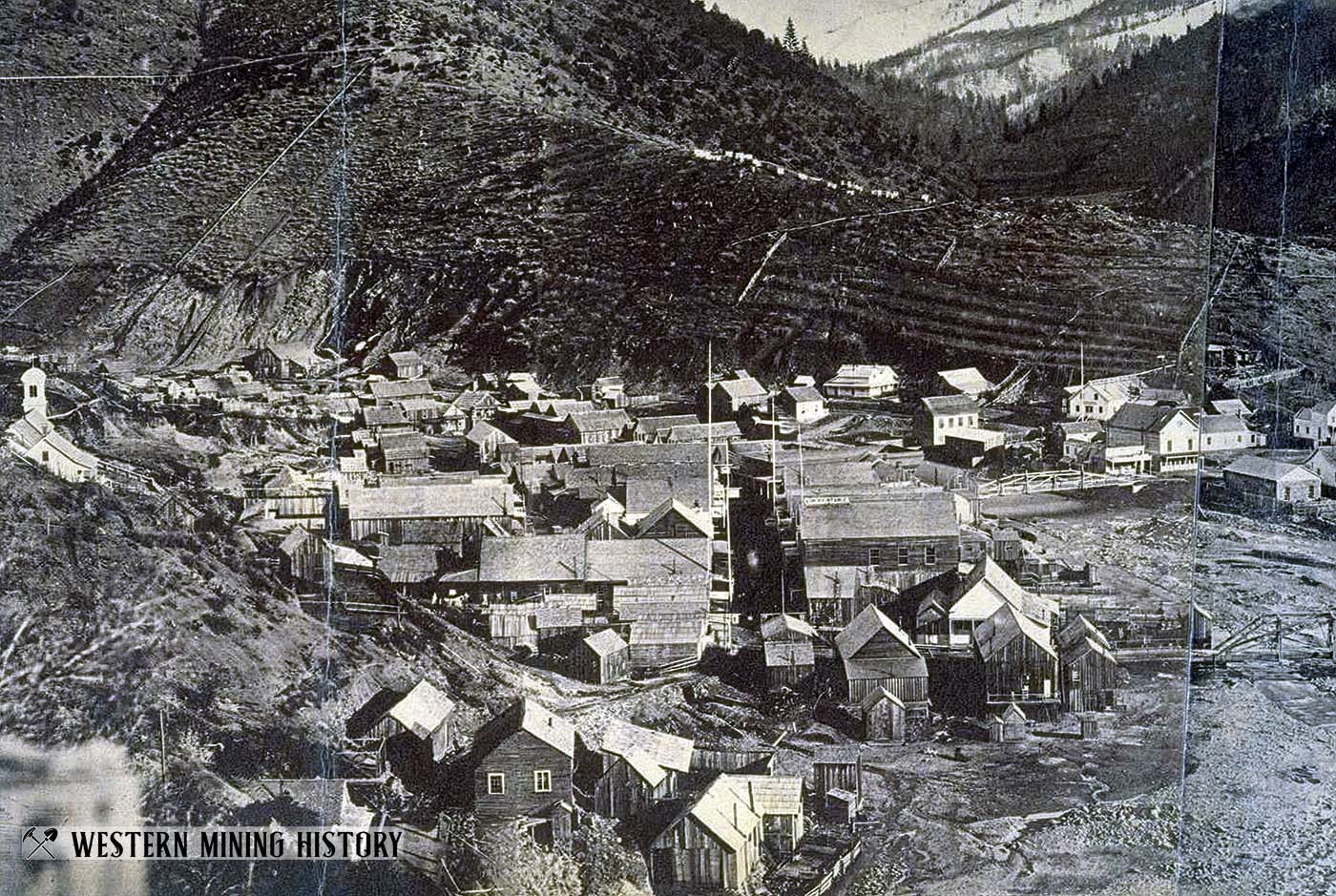

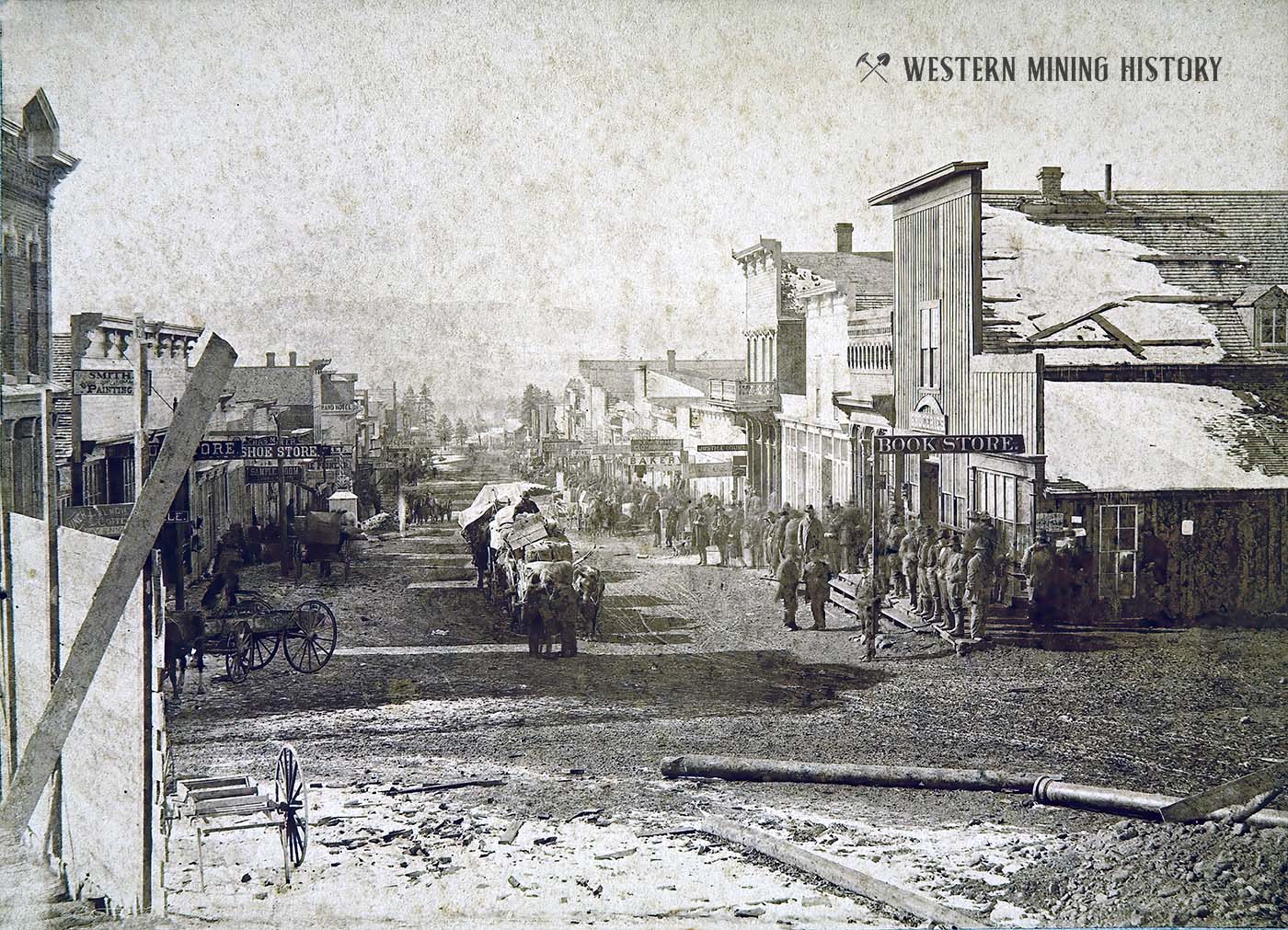

Featured Mining Town: Downieville, California

Downieville, California was settled at the convergence of the North Yuba and Downie rivers. Originally known as The Forks, the town was the site of some of the richest placer gold diggings ever discovered. Continue Reading

Featured Mining Town: Pioche, Nevada

Pioche, Nevada was the site of a significant silver rush in the early 1870s. Located at an extremely isolated region hundreds of miles from the nearest rail link, Pioche nonetheless became one of the of the largest towns in the Nevada. This was also one of the most lawless and violent mining camps in the West, notorious for frequent acts of murder and armed conflicts over the mines of Treasure Hill. Continue Reading

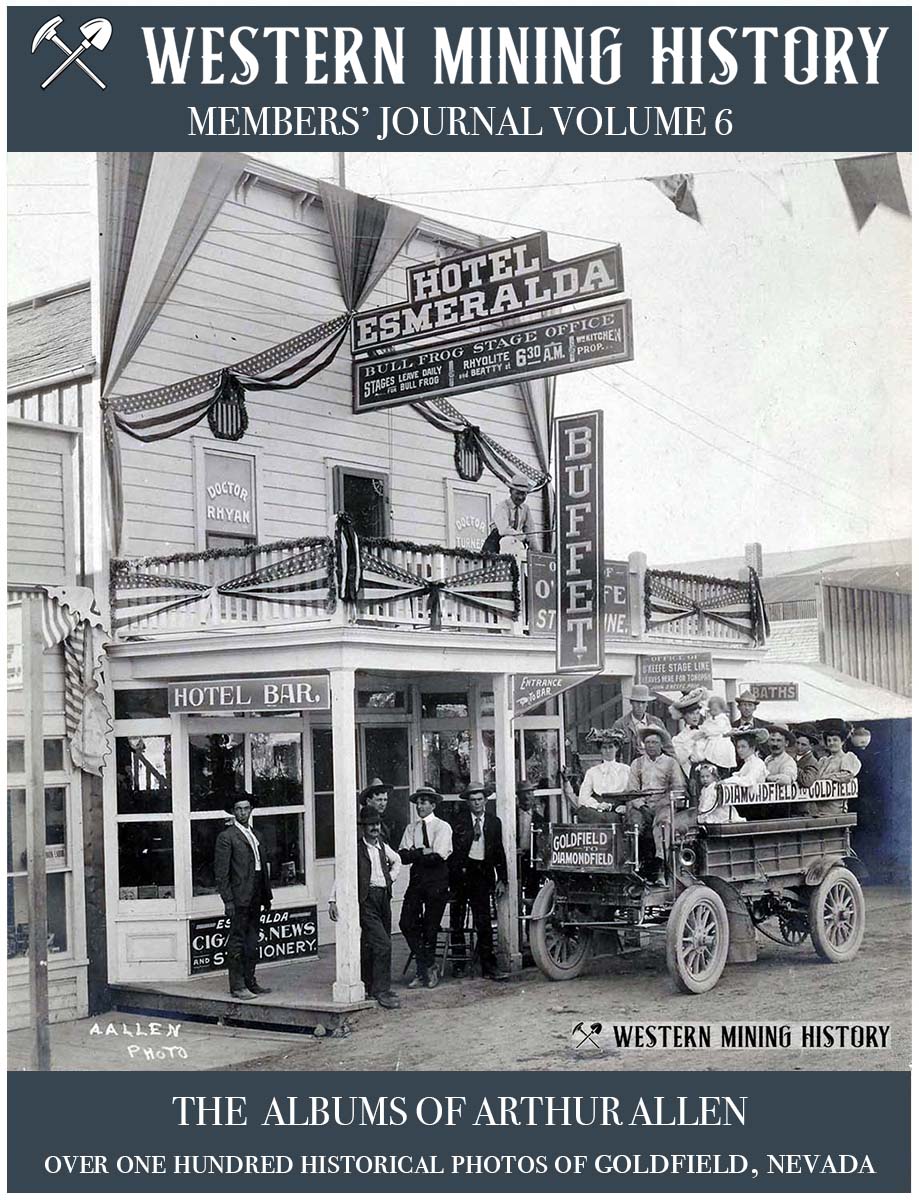

Goldfield, Nevada: The Arthur Allen Albums

Photographer Arthur Allen captured many important scenes from Goldfield, Nevada's peak years - from the budding camp that was just a collection of tents in the fall of 1903, to the thriving community that was described as "The World's Greatest Gold Camp", and was Nevada's largest city by the middle of the decade. "Goldfield, Nevada: The Arthur Allen Albums" presents over 100 photos of the city, the mines, and cultural events that occurred during Goldfield's boom years. Continue Reading

Featured Mining Town: Leadville, Colorado

Leadville, Colorado was one of the world's greatest mining cities. The camp grew to be a fabulous city in the clouds built on a mountain of silver. Continue Reading