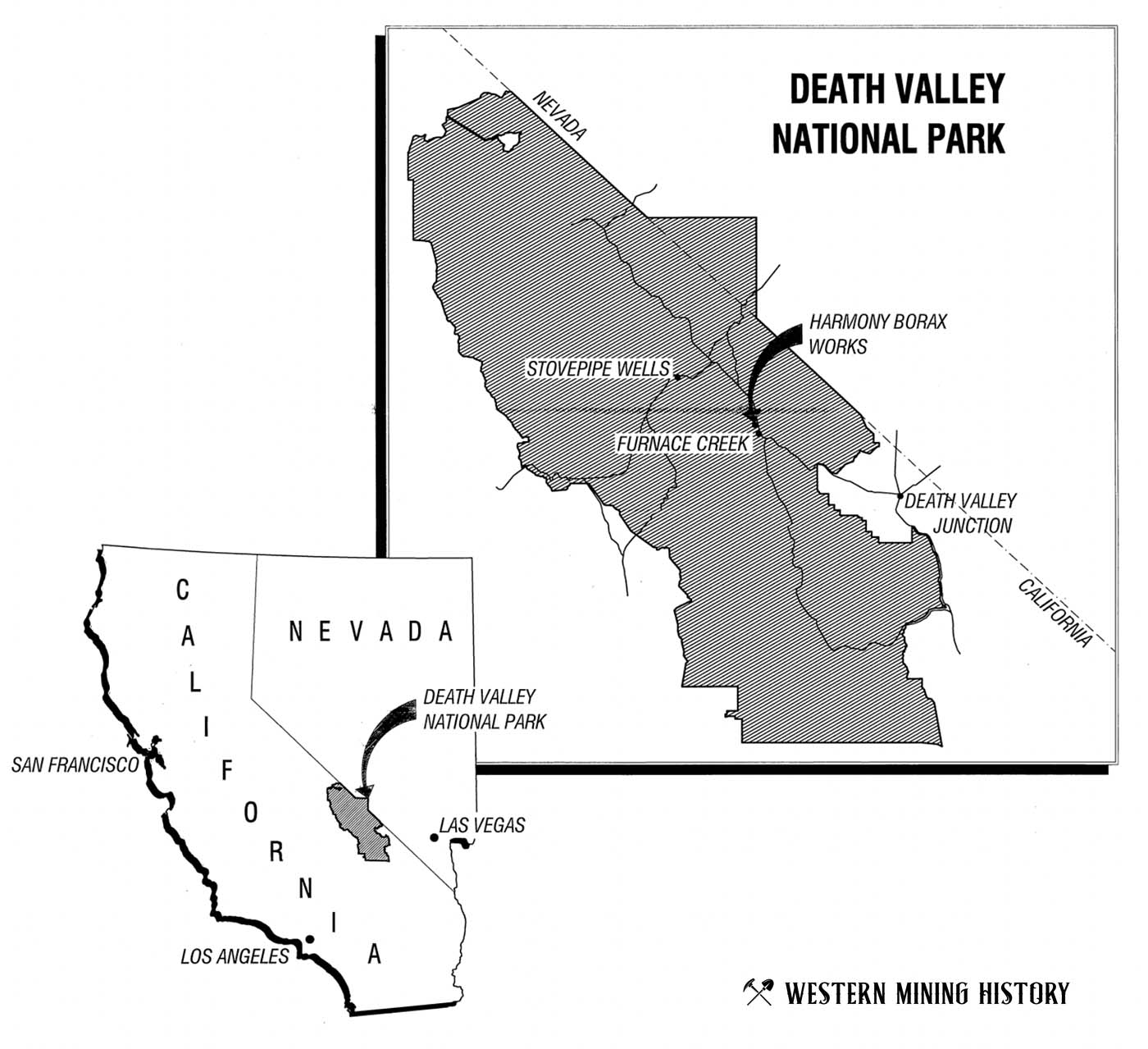

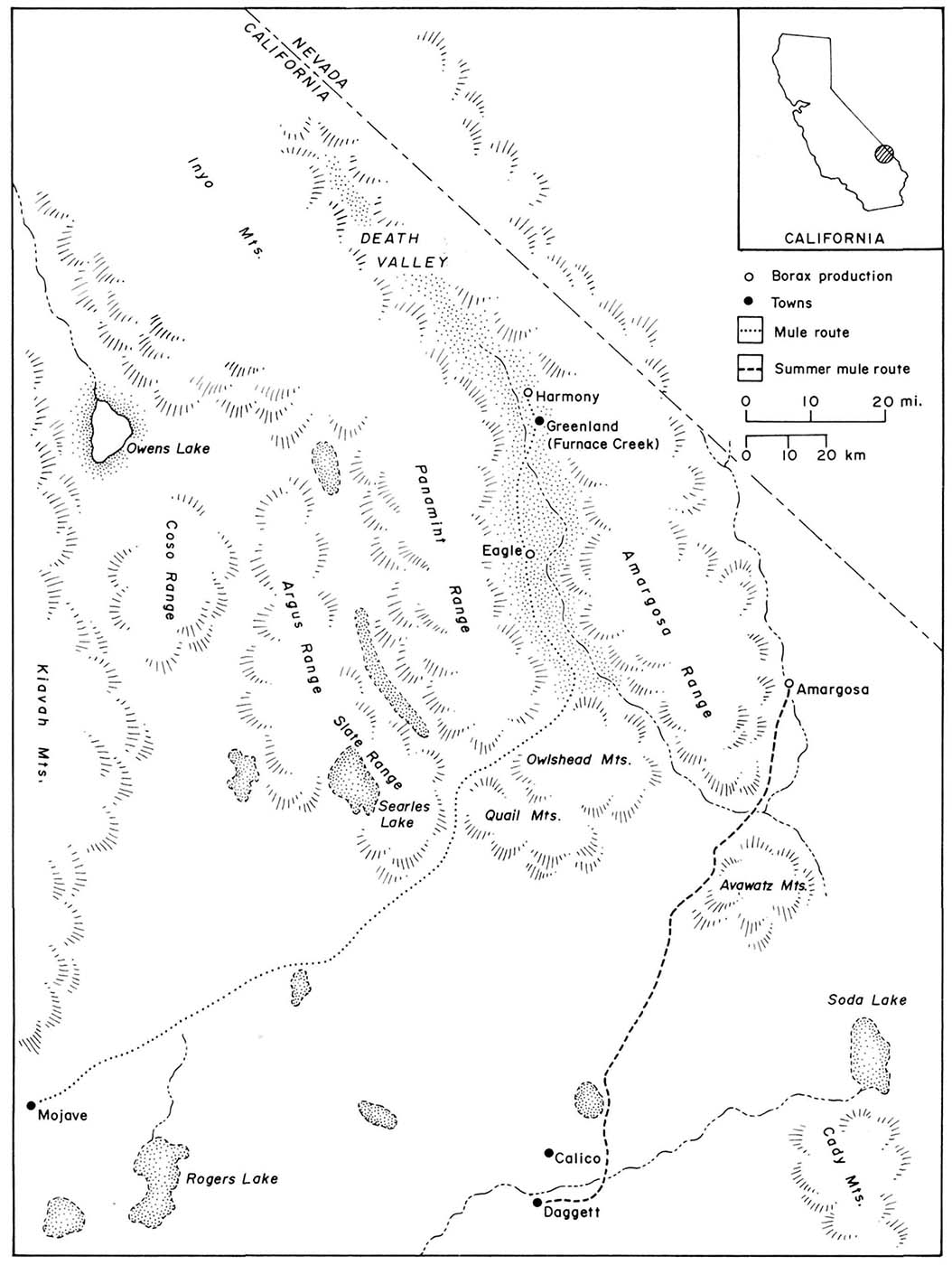

Borax was discovered at the ironically named Greenland section of Death Valley in 1881. Harmony Borax Works was processing borax by 1884 and was instrumental in the opening of Death Valley to commercial ventures.

Greenland became known as Furnace Creek Ranch – which now serves as the national park headquarters and is the hub of activity for the park.

Harmony Borax works ceased operations over 130 years ago, but the remains of the plant have been preserved and are on display near the park headquarters.

The historical marker at the site gives a brief synopsis of the borax works’ history.

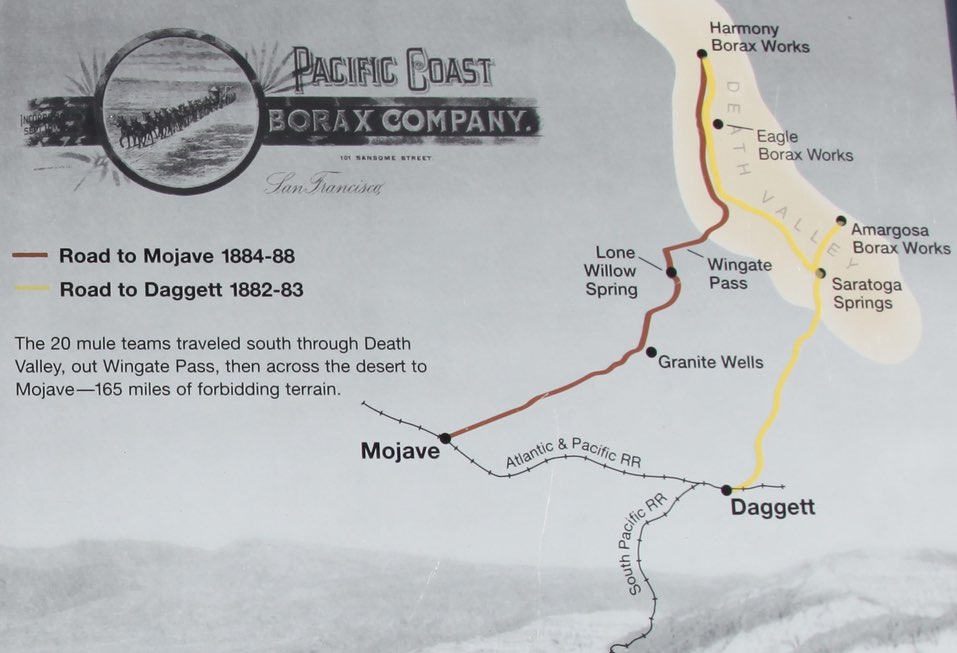

On the marsh near this point borax was discovered in 1881 by Aaron Winters who later sold his holdings to W.T. Coleman of San Francisco. In 1882 Coleman built the Harmony Borax Works and commissioned his superintendent J.W.S. Perry to design wagons and locate a suitable route to Mojave.

The work of gathering the ore (called “cottonball”) was done by Chinese workmen. From this point process borax was transported 165 miles by twenty mule team to the railroad until 1889.

Harmony Borax Works

The text in this section is from the interpretive signs at the Harmony site.

San Francisco businessman William T. Coleman built this plant to refine “cottonball” borax found on the nearby salt flats. The high cost of transportation made it necessary to refine the borax here rather than carry both borax and waste to the railroad, 165 miles across the desert.

Borax

Borates – salt minerals – were deposited in ancient lake beds that uplifted and eroded into the yellow Furnace Creek badlands. Water dissolved the borates and carried them to the Death Valley Floor, where they recrystallized as borax.

Borax – blacksmiths used it, as have potters, dairy farmers, housewives, meat packers, and even morticians. For centuries humans have exploited borax for many important uses.

Refining Borax

Workers refined borax by separating the mineral from unwanted mud and salts, a simple but time-consuming process.

Workers heated water in the boiling tanks, using an adjacent steam boiler. Winching ore carts up the incline, they dumped the ore into the boiling tanks. Workers added carbonated soda. The borax dissolved, and the lime and mud settled out.

They drew off the borax liquid into the cooling vats, where it crystallized on hanging metal rods. Lifting the rods out, they chipped off the now refined crystallized borax. To produce “concentrated” borax, they repeated the process.

Twenty Mule Teams

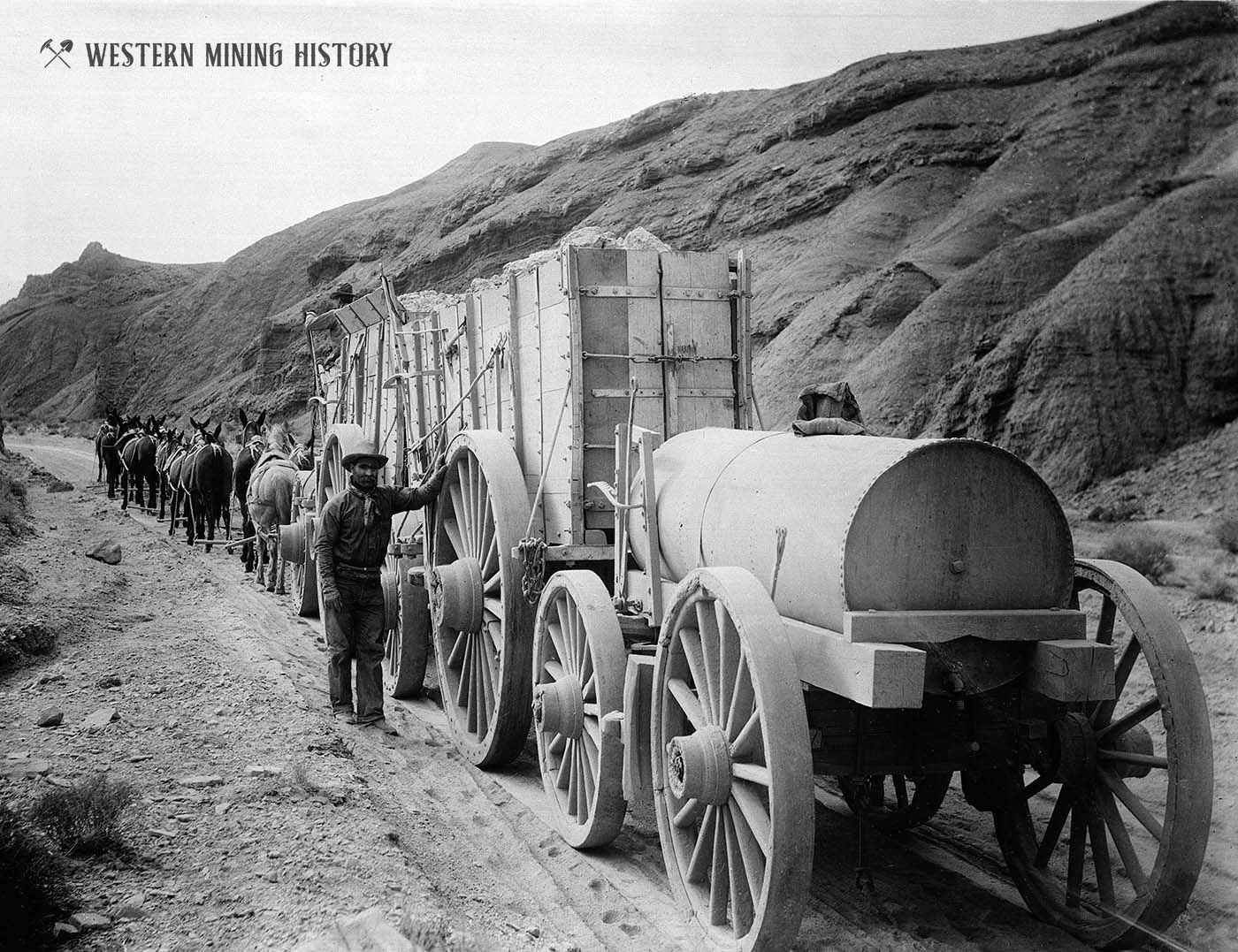

For more than a century the 20 Mule Team has been a symbol of the borax industry – on product labels, in history books, and on television. The status is well-earned; mule teams helped solve the most difficult task that faced Death Valley borax operators – getting the product to market.

The mule teams pulled loads weighing up to 36 tons, including 1,200 gallons of drinking water. The rear wagon wheels were seven feet high, and the entire unit with mules was more than 100 feet long.

Related: The Twenty Mule Teams of Death Valley

Living at Harmony

Crude shelters and tents once dotted the flat below the borax works. Chinese workers slept and at there; other employees lived at what is now Furnace Creek Ranch.

The financial problems of owner William T. Coleman and borax discoveries in other parts of California forced the Harmony operation to close in 1888 after five years of operation.

Full History of Harmony Borax Works

This longer history of the Harmony Borax Works is from a 1977 report by the National Parks Service.

Borax Production at Harmony

As already noted, Aaron Winters sold his borax claims near Furnace Creek to W. T. Coleman, along with the water rights to Texas Springs. By late 1881, the Death Valley Salt and Borax Mining District was formed. Surveyors were sent to the area to stake out the numerous claims being filed by interested parties. F. M. Smith’s name also appears on claims in the Furnace Creek area, indicating that he and Coleman were business partners during this early stage of borax development in Death Valley.

In late 1882, Coleman established a plant just north of Furnace Creek, near the marsh in which Aaron Winters had gathered his cottonball borax. The refinery was named the Harmony Borax Works. The same problems of high temperatures that had affected the Daunet plant near Bennett Well also afflicted Coleman’s operation at Harmony.

To compensate for this condition, Coleman purchased a borax claim near Resting Springs, just east of Death Valley. He was thus able to maintain production throughout the year by shifting his operation in the summer months to these Amargosa deposits.

The two areas were evidently developed by separate Coleman companies–Harmony Borax Mining Company and Meridian Borax Company–both incorporated in 1884.

Establishment

There is some question as to exactly when borax production began at the Harmony works. In 1883, Henry Hanks, the California State Mineralogist at the time, reported that the mining company had already located their grounds and settlement at the mouth of Furnace Creek.

The actual processing facility was being established on a nearby ridge, along with artesian wells. Evidently Coleman had set up the Amargosa works first, since Hanks reported the presence of 80 crystallizing vats there, which were about to commence production.

It is likely, then, that Harmony went into operation shortly after the summer of 1883. By May 1884, according to the San Francisco Mining and Scientific Press, the plant was producing “three tons of refined borax per day, besides shipping a great quantity in a crude state.” The company holdings consisted of the land and works at Harmony, a supporting ranch at Greenland, and included the borate fields surrounding Furnace Creek.

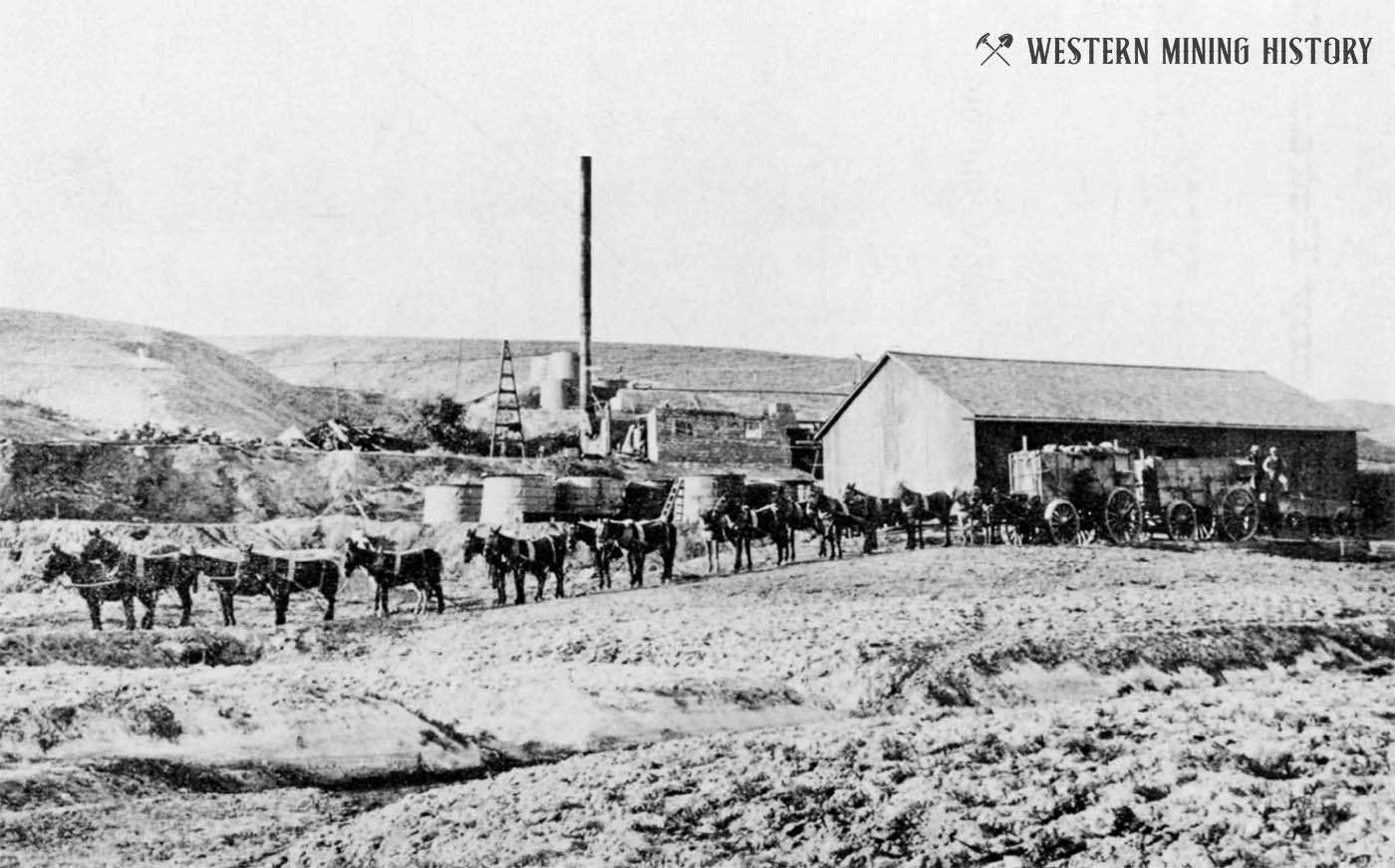

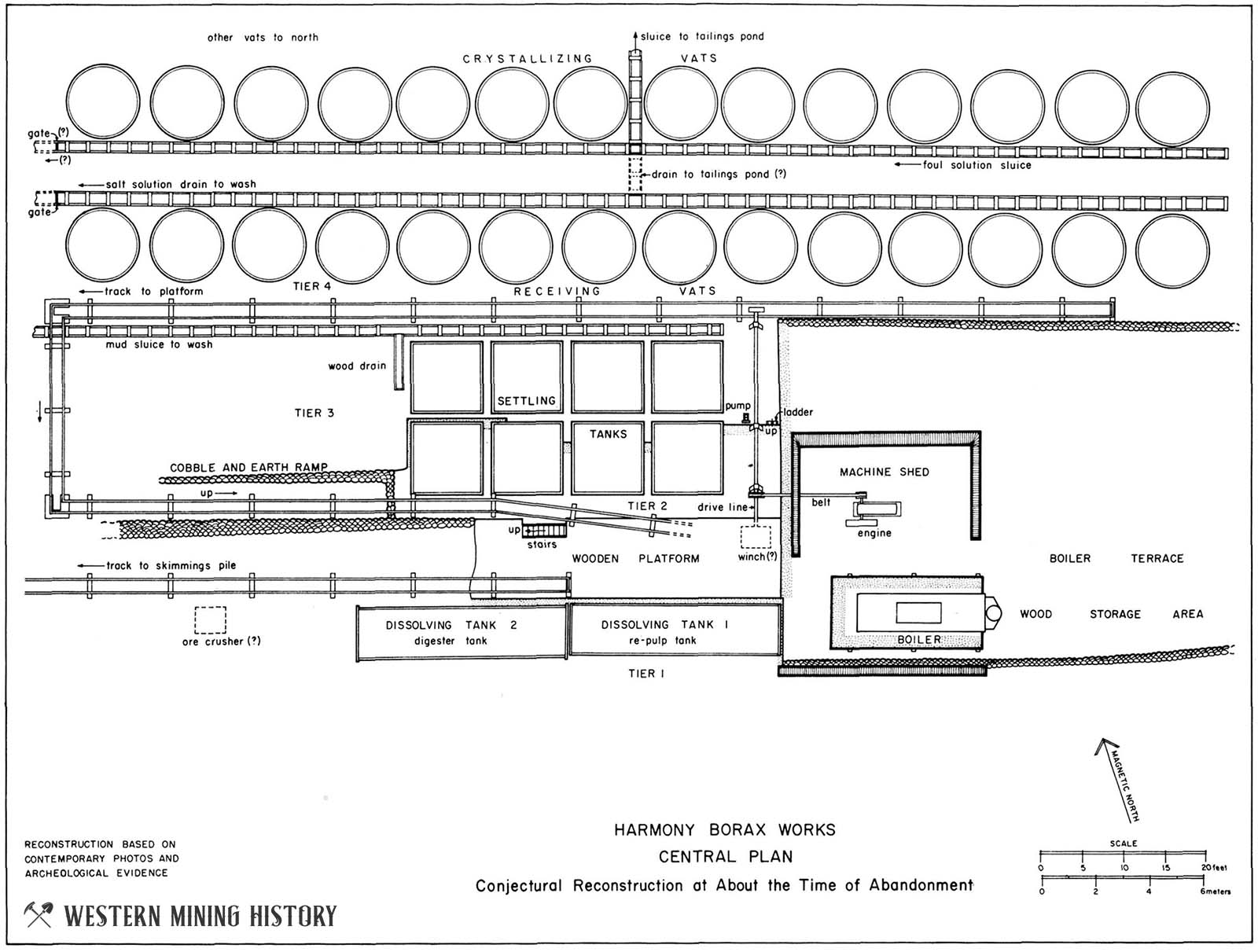

Harmony was established as a larger and more complex operation than the previous Death Valley venture at Eagle. Only fragments of documentary evidence remain on the physical plan of the site.

Coleman, or his field representatives, set up the manufacturing facility on a hillside near Furnace Creek. This positioning allowed for gravity flow, whenever possible, of water and solutions during processing. Overland piping connected water storage tanks on the top of the hill to Texas Spring, some three or more miles away.

A graded service road climbed up the hill from the salt marsh on the west and down to the wash on the east, thus allowing for a continuous flow of wagons carrying the unprocessed borax ore to the plant.

The plant itself was constructed on a series of four terraces, or levels of varying heights, each supported by cut sandstone, cobble rubble, or wood plank retaining walls. Adjacent to the service road, on the uppermost tier of the plant, were placed two large rectangular dissolving tanks of iron. Fronting the end-to-end tanks on the north were wooden platforms.

East of the dissolving tanks, on a slightly lower level, an adobe structure was built to house the boiler and to act as a machine room. An opening between the two sections allowed for natural air ventilation. At least two different roofing systems covered this structure and the dissolving tanks at various times, as seen in photographs of the site.

Wood to fuel the boiler was stored in the area east of the adobe structure. The west side of the plant was reserved as a skimmings pile. Here, grass and other debris mixed in with the raw ores was disposed of.

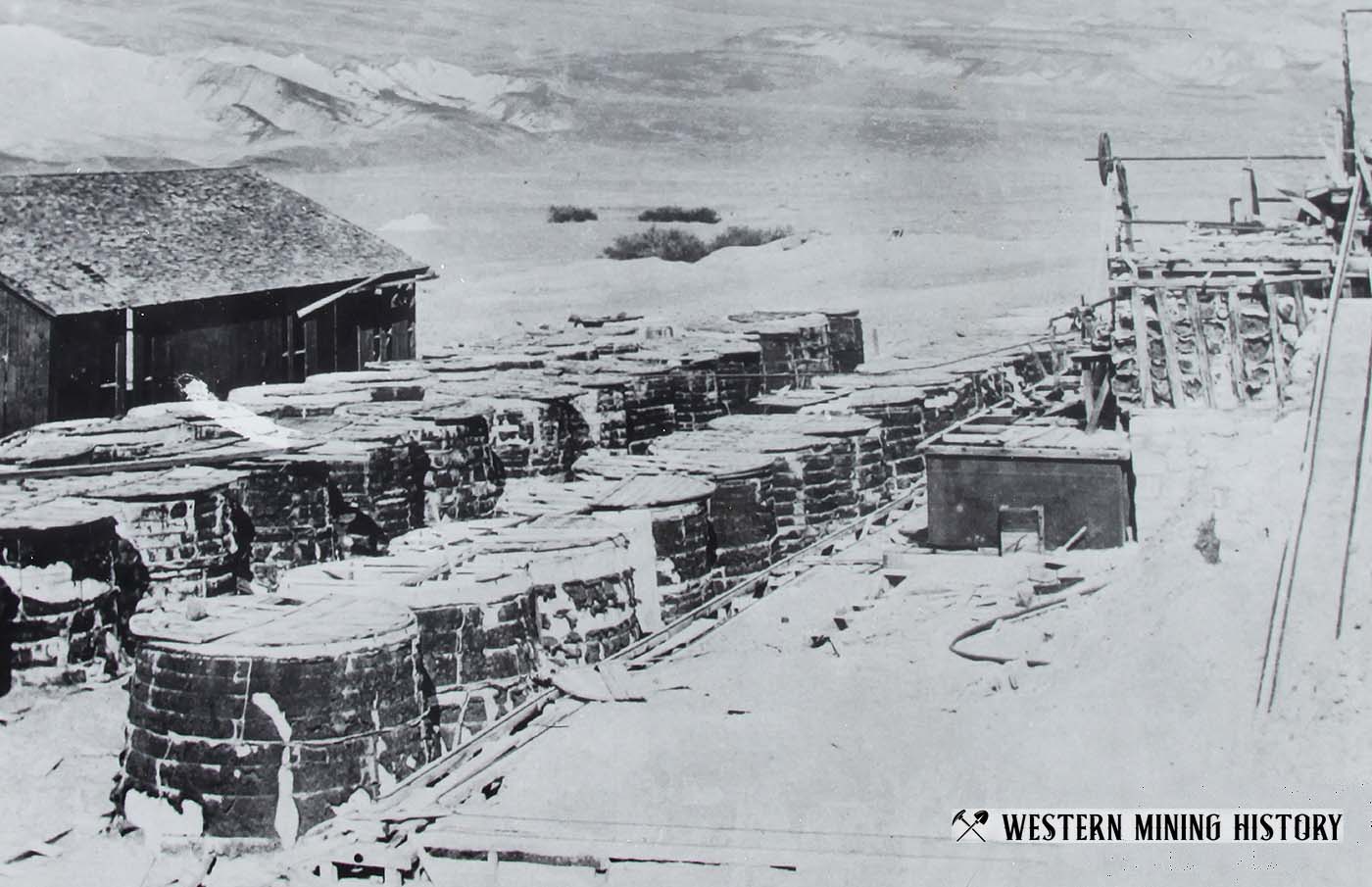

The next two levels down the hill contained square metal tanks housed in wood. Near these tanks and the dissolving tanks above were rail tracks for ore cars. The bottom level of the plant contained several long rows of crystallizing vats, with truncated cone shapes, and a wooden barn-like structure for storage.

According to the San Francisco Mining and Scientific Press, Harmony had 57 crystallizing vats, each holding 1800 gallons, and eight “receiving” tanks, with a capacity of 2000 gallons each. Three large earthen reservoirs were formed just across the wash to the north, to hold waste solutions.

A small town was established just to the north of the plant. Here the company supposedly housed employees and support facilities in adobe and wood structures, of which two adobe walled ruins remain today. Only a single photograph, dated 1892, shows what the settlement looked like, but even this is unclear.

A cluster of seven buildings can be seen, which probably consisted of an office, living quarters, and cooking and dining facilities for the men who worked at Harmony. Evidently only two of these buildings were constructed of adobe bricks. Two other structures are partially visible in an 1885 photograph. Both are constructed of wood planking, and possibly represent the blacksmith shop and a cooking and dining facility.

As Spears tells us, the Coleman company followed the example of other Death Valley settlers, and established a ranch at the mouth of Furnace Creek to support the borax operation. The name “Greenland” was given to the agricultural community. Eventually, with extensive irrigation, an oasis of sorts was formed in this otherwise barren region.

A half-acre pond was created by conducting the creek, with ditches and pipes, to a level stretch of ground. Irrigation ditches watered some 30 acres of land on which alfalfa, vegetables, melons, fruit trees, and natural grasses were cultivated. Spears also noted the presence of an adobe house with a wide veranda.

The next problem to be faced was getting the end product to Mojave and the railroad station. A road more than 160 miles long had to be constructed, using sledgehammers as grading tools. Water, naturally, was scarce on this long haul and, in some instances, watering places such as wells, springs, and water-tank wagons were more than 50 miles apart.

Operation

After the facilities at Harmony and Greenland had been established, it was necessary for production to get underway. While the boracic acid content of ulexite was slightly lower than that of some other borates, certain operational advantages were present. The process of extracting commercial borax from such borate ore was not complex, but it was time consuming.

Basically, the cottonball borate was scooped and shoveled off the ground, allowed to dry, and hauled to the plant by wagon or cart. Here it was crushed and dumped into large open water-filled tanks. As the water was heated by steam coils from a boiler, the mixture stirred by hand, the borax dissolved.

According to an 1892 account, carbonate of soda was mixed with the cottonball borax at this first step, apparently as a flux to get rid of such impurities as lime. Fuel for this operation was obtained in the neighborhood, while water usually came from springs or artesian wells.

The borax solution then, in some similar operations, went through various settling and receiving (mixing) stages. The solution, now of proper strength, was poured off into vats, commonly made of galvanized iron, where the water cooled and the borax crystallized either on the sides of the vats, or on plates or rods suspended in these containers.

In May, the vats were covered with layers of thick felt for insulation against the heat. Workers played a hose of water on the felt to lower the temperature by evaporation.

The borax remained in the crystallizing vats for from 10 to 14 days. The Engineering and Mining Journal for 1892 indicates that “if the crystals are dirty or impure, resolution and recrystallization may be necessary.” The residue water was generally recycled through the process.

The crystallized borax was removed from the vats, broken into chunks, and sacked immediately or stored in a building where it was later bagged for shipment to the railhead. Waste solutions were piped into earthen reservoirs where they could evaporate and be re-harvested.

To reach the railhead at Mojave, Coleman hitched 20-mule teams to huge borax wagons with a payload, in tandem, of over 20 tons. The teams usually consisted of two “wheeler” horses and 18 mules, and were handled by two men. Each of the five rigs pulled two large high-wheeled borax wagons and a water tank wagon, and could average about 15 to 20 miles a day.

The round trip usually took a little more than three weeks. Supposedly, 2.5 million pounds of borax were hauled from Death Valley each year by this method.

On the average, 40 men were employed at Harmony. Teams were coming and going all the time, and the settlers in Death Valley made the works a center of operations. Spears reported that the men at Harmony had the best food obtainable, and were housed “as men are in all mining camps.”

Workers with a variety of skills were employed by borax processing plants. Included were engineers, blacksmiths, teamsters, coopers, boilermen, watchmen, and common laborers. Pay ranged from $5.00 per day for blacksmiths to $1.25 per day for laborers, and included room and board, except for Chinese workers.

At Harmony a number of ethnic groups participated in the operation. Chinese workmen were responsible for gathering the raw ores from the ground surface and transporting them to the plant. Some sources state that local Paiute Indians supplied the mesquite and brush to fuel the boiler. Anglos made up the remainder of the work and managerial force.

Decline

In 1888, after only five years of activity, the Harmony Borax Works permanently closed down operations. This failure may be attributed to a fall in the market price of borax, along with the financial collapse of Coleman’s complex business interests, which led to his entire corporate holdings going into receivership.

In 1887, such quantities of borax were being imported from Italy that a drastic drop occurred in the value of borax. At the time, Coleman was extending his borax holdings in Death Valley and elsewhere. To finance his increasingly large and diversified interests, he had borrowed heavily. Coleman could not cover his loans when several banks unexpectedly called in his notes.

Coleman’s organization was sold in 1889 to Francis M. Smith, who consolidated his holdings into the Pacific Coast Borax Company. No effort was made to resume borax processing at Harmony, since Smith preferred to concentrate his attention on richer borate deposits in the Calico Mountains. Harmony and Amargosa were only to be held as reserves. The site was subsequently abandoned.

History of Borax Mining in California

Borax mining in Southern California’s Mojave Desert was made famous by the twenty-mule team wagon trains that were used to transport borax across the desert. This article takes a look at the history of borax mining in California.

Keane Wonder Mine

The Keane Wonder Mine was the site of one of Death Valley’s few permanent settlements. The ruins of the mine have been preserved within the boundaries of the National Park.

Wildrose Charcoal Kilns

Death Valley’s Wildrose Charcoal Kilns were built in 1877. Each kiln would be loaded with as much as 35 cords of wood and then lighted. The fire would burn for up to 8 days, and then need another 5 days to cool before the kiln could be unloaded.