The following text is from the piublication Mining Districts of Nevada by the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology.

By the time the Comstock was discovered north of the Carson River in the western part of what was to become Nevada, the district-type of organization had been used enough in California to prove its worth in protecting and legalizing mining claims and transfers. Nevada, then part of Utah territory and, like California, recently ceded to the United States by Mexico, had neither national nor territorial laws governing mineral claims.

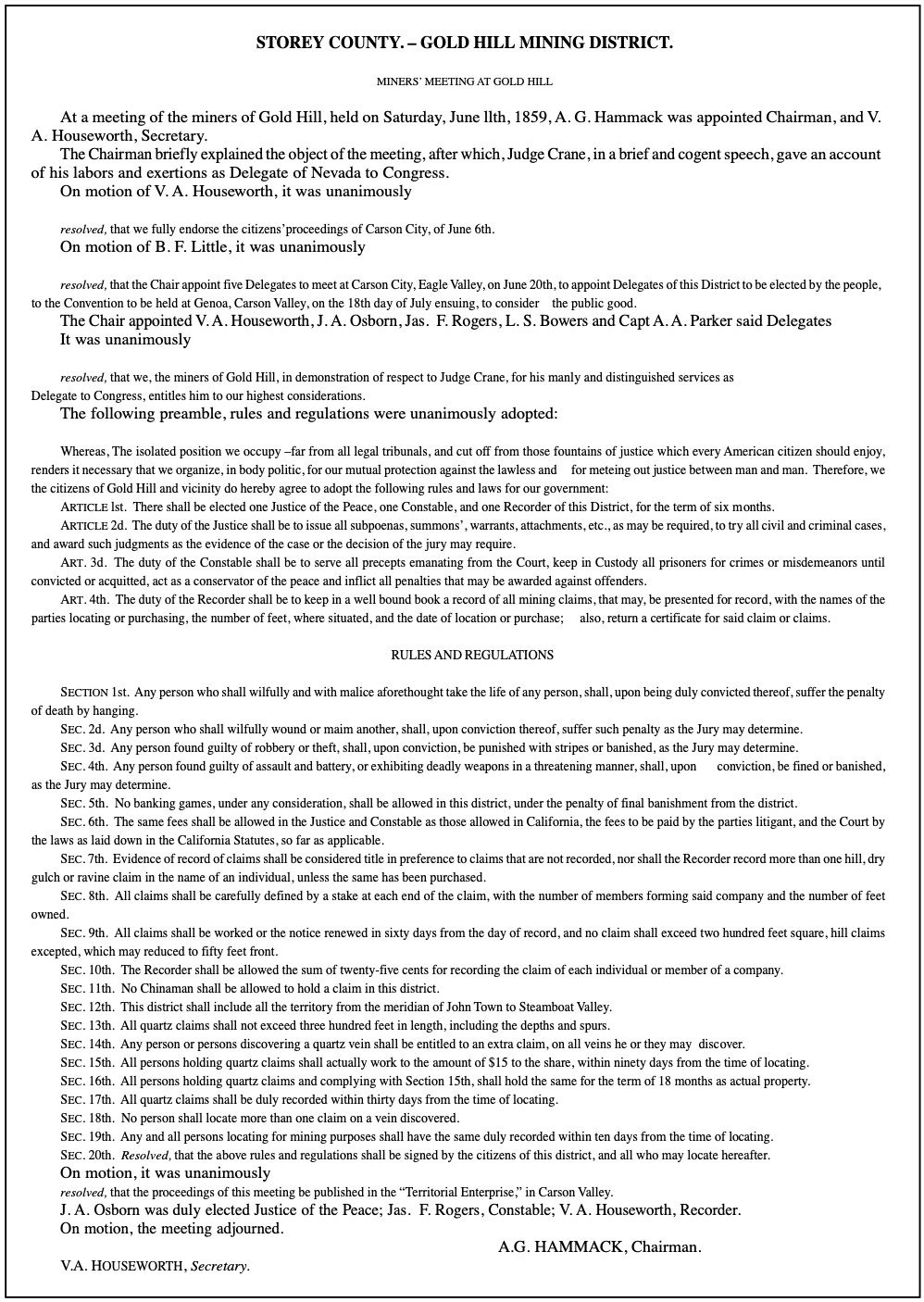

Following examples set on the Mother Lode, Comstock miners proceeded with the organization of a California-style district and, in January 1858, established the Columbia quartz district, taking in all of the Comstock lode, as the first mining district in Carson County, Utah Territory. The Columbia district quickly passed from the scene, however, as mining became focused around the small towns of Gold Hill, Virginia [City], and Silver City and the local miners broke away and formed their own districts. Figure 1 is the record of proceedings of the miners’ meeting held at Gold Hill on June 11, 1859 when the Gold Hill district’s rules and regulations were formulated.

Several articles clearly show California’s influence on the new Nevada industry, and also demonstrate the custom of intertwining of civil and mining matters in mining district regulations.

The Comstock is credited with the first official “mining district” formed in Nevada, but the first organization for mining, probably similar to a mining district in all but name, was formed in southern Nevada in 1856. On July 29 of that year, a group of 15 Mormon missionaries formed an association to work the Potosi lead mine in the Potosi (Goodsprings) district. Although the venture failed and the southern Nevada discovery was eclipsed by Comstock excitement, Potosi may well have been the first mining district in Nevada.

Mining may have taken place as early as 1849 at the Desert Queen mine, west of the Forty Mile Desert section of the emigrant trail. There is, however, no record of a mining district being formed at that early date.

The spread of mining districts outward from the Comstock after 1859 is commonly compared with “ripples spreading from the drop of a stone in a pool of water.” Numerous districts were formed in the mountains of western Nevada, first flanking the Comstock then skipping to discoveries to the southeast along the California border, then spreading as well from other discoveries made at points such as Reese River and Buena Vista in the central part of the state. Following the now common practice, miners in each of the new districts called meetings and set down the rules they would thereafter follow within their local area.

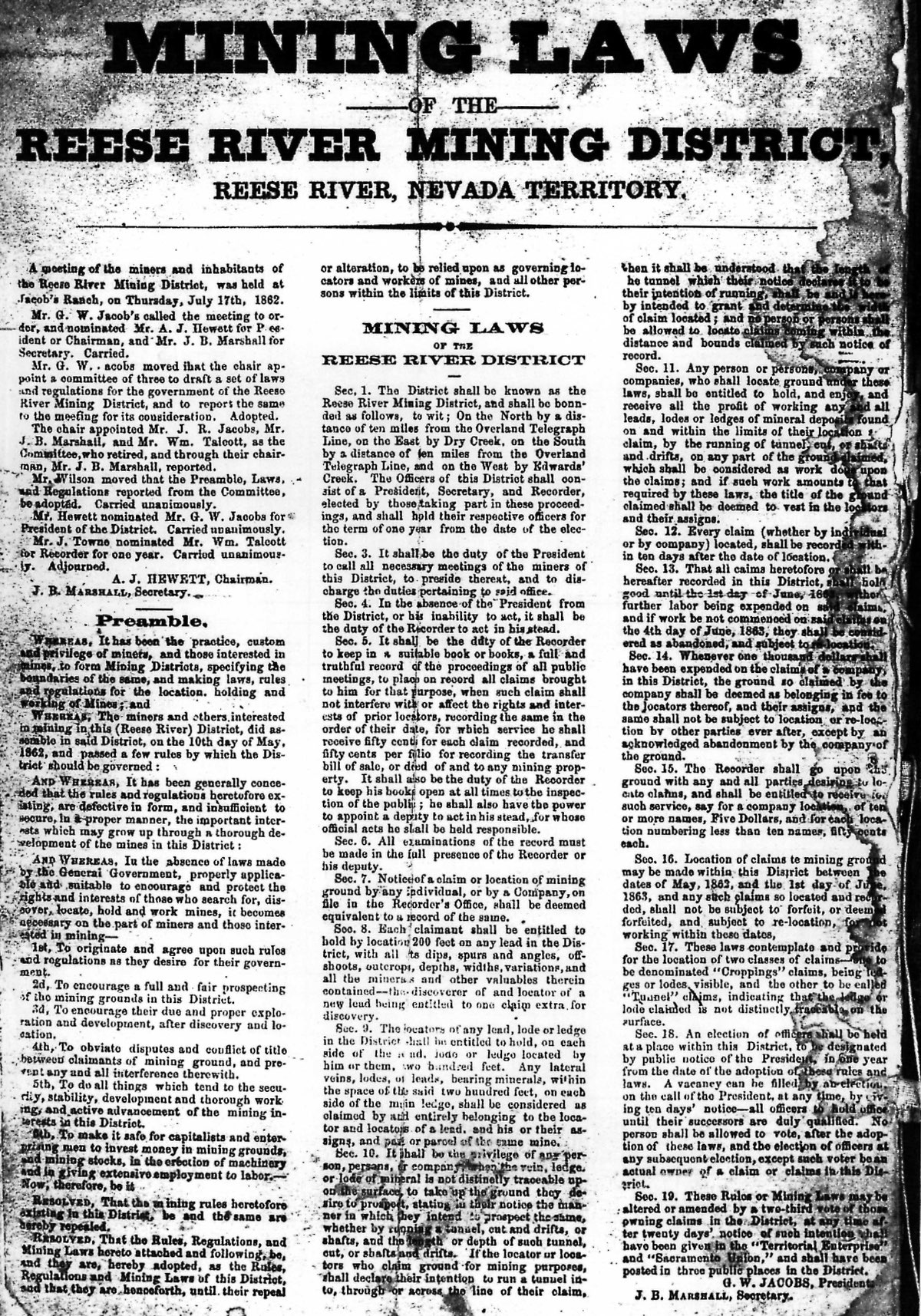

Figure 2 shows the format devised by miners in the Reese River mining district of Lander County in 1862. In contrast to the earlier Comstock rules (fig. 1) these now addressed only mining matters. In 1866, the Nevada State Legislature enacted legislation setting up a statutory procedure for establishing a mining district and electing a mining district recorder. The act, in addition to the provision relating to mining districts, covered rules for the location of mining claims, for performing assessment work, and for establishing recorder’s fees (Laws of Nevada, Second Session, Chapter LXL, approved February 27, 1866).

This act, however, contained provisions in direct conflict with mining legislation enacted by the U.S. Congress in 1866, and the Nevada statute was repealed the following year (Shamberger, 1974, p. 63). Although subsequent acts of the Nevada State Legislature mentioned mining districts and mining district recorders (for example, Laws of Nevada, Ninth Session, 1879, Chapter LXXII, Twelfth Session, 1885, Chapter XXI, and Twenty-Third Session, 1907, Chapter XCI), no provision for the creation of a mining district was ever again enacted (Shamberger, 1974, p. 63). The 1879 legislation did, however, provide that, if a county seat were located within a mining district, the county recorder would be the mining district recorder.

Since the last pieces of legislation mentioned have never been repealed, it seems possible that even today in a new mining district distant from a county seat, miners could get together, name and describe a new mining district, and elect a mining district recorder.

By 1867, when the first Nevada State Mineralogist’s Report was issued, mining was active in 114 separate districts within the state. In the first listing of western mining districts compiled by the U.S. Geological Survey, Nevada was credited with 182 districts, and Lincoln, in his comprehensive study of Nevada mining districts in 1923, described about 309 districts. Schilling (1976) listed 344 districts on his map, Metal Mining Districts of Nevada, and the present study identifies 526 districts and areas within the state boundaries.

These variations in number, however, do not entirely represent increases in districts over time but also reflect major changes in the definition and concept of the mining district. Early reporters such as Stretch (1867) and Angel (1881) tended to report only districts “organized” in the fashion of the time preceding adoption of the Mining Law of 1872. Lincoln (1923) and Schilling (1976), however, did not restrict themselves to organized districts, a concept that had largely fallen into disuse well before the time of Lincoln’s work.

The notable increase in numbers of Nevada districts between 1976 and this study reflects, first of all, the inclusion of many obscure and minor districts that were overlooked by earlier workers. Of equal importance, however, the increase also represents the inclusion of many localities where prospecting or mining is known to have occurred or where concentrations of specific types of mineral occurrences are known to exist, but which were never included within an organized mining district.

Many writers, including Bailey and Phoenix (1944), Lawrence (1963), Garside (1973), Johnson (1977), and Kleinhampl and Ziony (1984), used terms such as “mining area” or just “area” to describe these localities. Many of these localities, with continued use, have now come to be called mining districts and are listed as districts in this report. The present study also includes nonmetallic (industrial) mineral districts, a category included by Lincoln but not by Schilling.

Mining district names present a problem that, in some cases, defies a clear solution. Some indication of the magnitude of this problem can be seen from the numerous alternate names listed for many of the current Nevada mining districts (see plate 1). Many of the early mining districts, formed following local mineral discoveries, quickly fell into disuse when the mineral showings failed to develop into worthwhile ventures. Meanwhile, miners continued to form new districts with new names, sometimes incorporating parts of several older districts in the new ones. Even names of historic, established districts change as new mines are found and become prominent.Evidence of continuing name change can be seen in several districts at the present time. In Elko County, for example, the name for the district surrounding the town of Midas, historically known as Gold Circle, appears to be evolving, through local usage, to Midas. In the Independence Mountains of northern Elko County, the old Burns Basin district, surrounding some small antimony prospects, has been engulfed by the huge Independence Mountains district that includes the extensive disseminated gold deposits developed there. A similar change may be also be underway in the active gold belt of northern Eureka County and southwestern Elko County, where the Old Bootstrap, Lynn, Maggie Creek, Carlin, and Railroad districts are being grouped into a new super district known as the Carlin trend.

This huge new area is a far cry from the concept of a mining district as created by the ’49ers in California but is an example of what may be the modern concept of a mining district-an area encompassing mineral deposits that are geologically similar or are genetically related.