Gold dust was discovered in the Carson Valley as early as 1848 by Mormons traveling to the gold fields of California. However, with seemingly better prospects on the other side of the Sierra, and with supplies dwindling after the long desert crossing from Salt Lake City, nobody stayed to work these placers until at least 1850. By 1851 a small and remote mining colony had formed and was known as the "Gold Cañon Placer Mining Colony", located roughly where the town of Dayton still is today.

The remote and isolated colony was an unusual mix of prospectors and Mormon settlers, and was loosely governed by Mormon law. It was the miners of Gold Cañon that would eventually discover Comstock Lode. Life at this settlement was detailed in the 1883 publication "Comstock Mining and Miners" by Eliot Lord, and the following text is part of that account.

The organization of the early western mining communities was a simple autonomy, and the little colony scattered along the line of this ravine was a model of its kind. The authority of the national government was merely a name. Until September, 1850, the Gold Creek placer was on an unorganized portion of the national domain, and it lay beyond the undescribed circle over which the Mormon governor and priest ruled as caliph, though nominally within the limits of the independent State of Deseret.

The miners acknowleged no magistrate or arbiter, and the placer was apportioned according to a rude notion of equity, or prior occupation, or tacit consent.

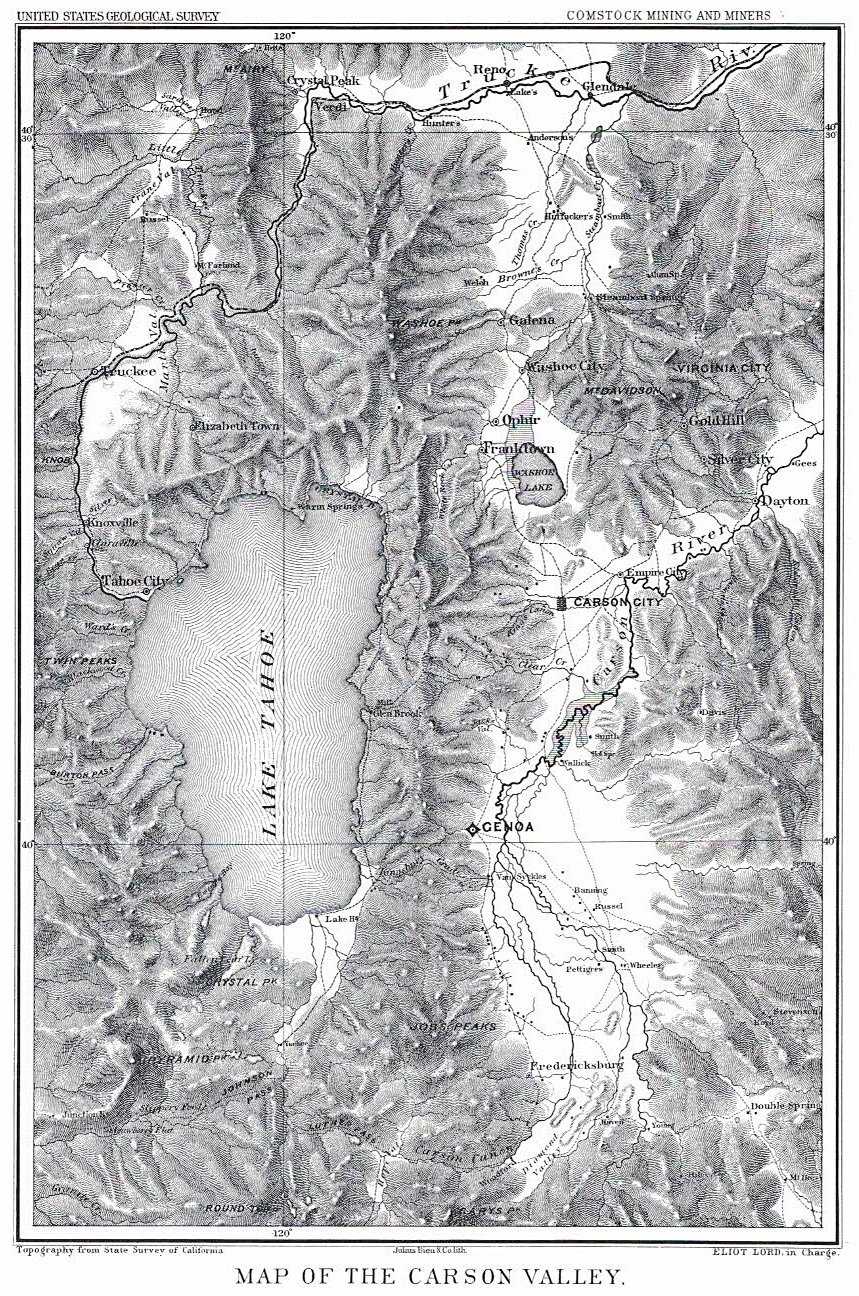

Additions were made to the colony from time to time, and parties set out on exploring expeditions to the headwaters of the Humboldt River and Goose Creek, to the Walker River, 30 miles east of Carson Valley, and to the Truckee River, 40 miles north. Reports were brought back of rich surface diggings, but the majority of the miners preferred to remain at Gold Cañon. The gravel was worked with rockers and long toms, and yielded from $5 to $10 per day to the man on the average, nearly 200 being at work during the autumn of 1851.

Attracted by the opportunities of trading with the overland emigrants and by the fertility of the land along the banks of the Carson River, John Reese and other Mormon pioneers took up little farms and ranches in the valley during the spring of 1851, and found a ready market for their crops and cattle.

Their relations with the miners were at first friendly, although they had some cause to regard the placer workers as a camp of Ishmaelites; for when provisions were scanty, in the winter of 1852-3, the miners held a little meeting and concluded to supply their wants by the inexpensive method of a foray.

Accordingly, a party made a sally from their camp and waylaid two trains moving from Salt Lake to Genoa, a little settlement which had grown up since May, 1851, about the farm of John Reese. The bold stand taken by the train men saved their bacon, for the assailants did not expect to meet with armed resistance and retired ingloriously.

The natural line of separation between the peace-loving, stolid Mormon farmers and the reckless, bustling placer miners was drawn more deeply by such acts as this. Besides, the cañon workers had little occasion to mingle with the people of the valley. A station house was built at the foot of the ravine in the winter of 1853-4, where provisions, liquor, clothes, and all needed supplies could be obtained, and a combined store, saloon, and bowling-alley was erected shortly afterwards at Maiden Bar, one and a quarter miles farther up the cañon."

In the autumn, after the summer heat was passed, the creek swelled even before any snow had fallen and the seepage from the hills increased. Then miners began to flock to the placer from California and to work in the bed of the cañon and the neighboring ravines. As the water sources grew dry in May or June the placer was then generally abandoned, and only a few miners remained along the slender line of the creek. Whether the colony was large or small, however, miners and farmers stood aloof from each other, though without any positive antipathy.

By act of Congress, approved September 9, 1850, the territory of Utah had been established, but the Carson Valley settlers had been left without any district judge or magistrate until the formation of the county of Tooele, (March 2, 1852), embracing a tract so extensive that the settlers on its western border found the county organization of but little use.

The increasing importance of the valley settlements and their complaint of the lack of all legally constituted authority finally induced the legislative assembly of Utah to pass an act, approved January 17, 1854, organizing the county of Carson and defining its boundaries, north by Deseret County, east by the 118th parallel of latitude, south by the boundary line of Utah Territory, and west by California.

By the same act, the territorial governor, Brigham Young, was “authorized to appoint a probate judge for the county when he shall deem it expedient, and this judge, upon his appointment, shall proceed to organize the county by dividing it into precincts and causing elections to be held by law to fill the various county and precinct offices." Orson Hyde, a prominent Mormon elder, was accordingly assigned to the charge of the county as probate judge, and set out with a small escort from Salt Lake (May 17, 1855) for the valley of the Carson

By act of the Utah assembly, approved February 4, 1862, the probate judge, besides discharging the ordinary functions of his office, was empowered to exercise original jurisdiction in both civil and criminal cases. He was also constituted chairman of the county commissioners, and was intrusted with the arduous duty of conservator of the peace throughout the county. There was a provision for an appeal, under bonds, from his decisions to the supreme Court of the territory," but practically Hyde, as probate judge, was the ruling magistrate of the district, though the miners showed no regard for his commission. But in the valley his arrival was heartily welcomed.

The life of the simple people whom he there governed was not unlike that of the peasants of Acadie. They labored only to supply their humble wants. Even tempered as their draught oxen, and matching them also in slowness of thought and of action, they built their rude cabins of logs thatched with shakes, tilled their fields along the river banks, gathered their little crops, and troubled their minds about nothing except seed time and harvest. They looked up to Hyde as their spiritual as well as temporal director and received with unquestioning faith his inspired teaching.

The harvest of 1855 was a meagre one, but the chosen people of Carson were fed by miraculous bounty. Hyde described this special providence in a letter to the Placer American, announcing that "honey dew had fallen so bountifully on the small cottonwood along the river banks that the citizens were washing the leaves and boiling the syrup into sugar," and interpreted the prodigy by adding: “The people depended on their wheat to get groceries, but when the wheat failed, sugar fell from heaven."

A Gentile physician and naturalist, who noted the same phenomenon, wrote to the Sacramento Union that this blessed manna was the "product of secerning tubules opening on the posterior part of the insect termed aphides or plant lice, of the family Hemipterae." The miners laughed at the sugar from heaven, but the pious faith of the Utah peasants remained unshaken.

Their peaceful life was disturbed somewhat by the entry of a rough unruly set of ranchmen into Washoe Valley and upon lands lying along the Truckee River, who disputed the possession of the grazing pastures with the Mormons and the cattle-owning Indians; but the early settlers held their ground, in most instances, until they were commanded to gather up all their movable possessions, abandon their homes, and repair to Salt Lake City by a ukase of Brigham Young-issued when the safety of his church and people were menaced, as he averred, by the presence of the little army of United States troops under General Albert Sidney Johnson.

The message reached the valley by express at nightfall, September 5, 1857. There was no thought of disregarding the summons or of questioning its necessity. At the bidding of their leader they would have entered the jaws of death with dull obedience, a temper midway between the unreasoning docility of sheep and the masterful sense of duty which drew on the Six Hundred at Balaclava.

Accordingly, on the 26th of September, 1837, the Mormons of the valley, about 450 men, women, and children, all told, abandoned their farms and formed in a well-ordered procession, marshaled by captains of tens and hundreds, driving their cattle before them and carrying their household goods to the city across the desert.

The Probate Judge, Orson Hyde, had gone to Salt Lake in the autumn preceding, leaving Carson Valley November 6, 1856. Shortly after his arrival at Salt Lake City, December 9, 1856, Carson County was attached to Great Salt Lake County for election, revenue, and judicial purposes, by act of the territorial legislature, approved January 14, 1857, and the probate and county court records were delivered over to the order of the probate court of Great Salt Lake County.

The determining cause of this action is said by the authorized spokesman of the church to have been the disturbed condition of Western Utah at the time; but, perhaps, a more sufficient reason may be found in the distance of the Carson settlement from the Mormon metropolis, the expenses of maintaining a separate county organization, and the unwillingness of the judge assigned to the district to cross a desert to hold his court.

The miners at Gold Cañon knew of the departure of the Mormon settlers and the loss of their judicial privileges, but regretted neither. They had never mingled sociably with the Mormons of the valley, and only a few of the departing settlers had attempted to join them in mining on the cañon. No cases were submitted to Judge Styles, and when application was once made to Orson Hyde to adjust a dispute he sensibly remarked that he "didn't propose to mix himself up with any Gentile messes."

The miners, left to their own devices, contrived to live together amicably as a rule. Disputes were settled informally by reference to associates and friends, or each contestant named an arbitrator, and the two referees so chosen selected a few associates to sit with them in judgment upon the case.