The great body of miners had contented themselves with the small but certain returns from the bed of the cañon and the creek delta at its lower end, but there was one noteworthy exception to this general practice. Two young Americans, Ethan Allen and Hosea Ballou Grosh, made a persistent and well-planned effort to trace the metal-bearing ledges of the district.

The story of their work is a memorable scene in the drama of mining industry. Never was the strange allotment of the favors of fortune more vividly set forth than in their fate as contrasted with the blundering luck of the ignorant prospectors who followed in their foot steps.

They were brothers, sons of a Universalist clergyman, living in 1849 in Reading, Pa. Allen Grosh, the elder of the two, was born in 1824 (November 11th), and his brother in 1826 (August 3d), at Marietta, Pa. The news of the discovery of gold in California stirred their minds with the same impulse which was given to thousands like them, and they joined a party which set out for the Pacific coast, sailing from Philadelphia on the 28th of February, 1849, for Tampico, Mexico.

A storm which struck their vessel before reaching port, driving it back on its course, and a bolt of lightning which shivered a mast, might have seemed an ominous outset to their expedition, but the spirits of the two young men were too buoyant and self-reliant to be weighed down by presages of evil.

Reaching Tampico at length, on the 26th of March, they crossed overland to San Blas, enduring with invincible good humor and patience the bitter discomforts of the overland journey, scarcity of water, a burning sun, "a barren country with few trees and these almost leafless, stampedes and straying of mules and horses, poor provisions, insults of all kinds day and night, bad roads and in places no roads, and attacks of malarious fever and dysentery.

The contractor who had undertaken to provide their transportation to California, and had been paid in advance, declared his inability to fulfill his agreement while the company were still 80 miles from the west Mexican coast, but nevertheless, the party struggled on, reaching San Blas upon the 23d of June.

Like most of their companions, the Grosh brothers had not thought it necessary to bring a surplus to a land of gold after prepaying their passage, and were left behind accordingly by the steamship which touched at San Blas on its way up the coast shortly after their arrival.

Nothing discouraged, they contrived to obtain a steerage passage on the bark Olga, which sailed from San Blas on the 12th of July, by selling their share of the mules and horses, taken by the concession of the defaulting contractor, and pawning the wagons and harness as security for the balance of the passage-money. On the 30th of August the barque entered San Francisco Bay, but Hosea Grosh was still so ill with dysentery and malarial fever, contracted on the passage through Mexico, that it was several weeks before he was able to do any work.

During his sickness his brother cared for him most tenderly and patiently, although he had chased, naturally, at the extraordinary delays of the journey and longed to set off with the parties departing daily for the gold-fields. When Hosea regained his health it was necessary to provide an outfit, and the brothers were not able to begin work as prospectors until the summer of the year following (1850), in El Dorado County, California.

Their chances of success, based on personal fitness for their undertaking, were unusually fair. Others were young, strong, and hardy, like them, but few of their fellow workers were so observant, industrious, and temperate. They had studied and reflected more than most men of their age, and knew something at least of elementary chemistry and mineralogy. Always cheerful, hopeful amid all discouragements, honorable in small things as in great, they gained the respect of all their companions, though they were somewhat reserved in disposition and confided in few intimate friends.

The miner who knew them best has written of them that they were “in truth religious, not apt to talk about it, not wedded to any special dogma, but filled with that genuine religion of the heart which is the salt of the earth, and which keeps whoever possesses it, as it kept them, fearless, earnest, and pure."

Their first season at the mines was moderately profitable. They saved $2,000 above their expenses, but afterwards spent all their savings to no purpose in diverting the current of a river from its bed in order to wash the sands of its old channel.

In 1853, after two years of generally unremunerative work, they crossed the Sierra Nevadas for the first time, and joined the parties of miners at work along the line of Gold Cañon. Here they made only a bare living until the autumn of 1854, when they returned to California in order to prospect for gold-bearing quartz-veins at Little Sugar Loaf, in El Dorado County.

Their bad luck continued. On the 31st of March, 1856, they wrote to their father: "Ever since our return from Utah we have been trying to get a couple of hundred dollars together for the purpose of making a careful examination of a silver lead in Gold Cañon. *** Native silver is found in Gold Cañon; it resembles thin sheet-lead broken very fine, and lead the miners suppose it to be. *** We found silver ore at the forks of the cañon. A large quartz vein shows itself in this situation."

They went to Utah for the second time in September, 1866, staying at Gold Cañon until the end of October. In a letter dated November 3, 1856, they wrote: "We found two veins of silver at the forks of Gold Cañon. *** One of these veins is a perfect monster." And again, November 22: "We have hopes almost amounting to certainty of veins crossing the cañon at two other points."

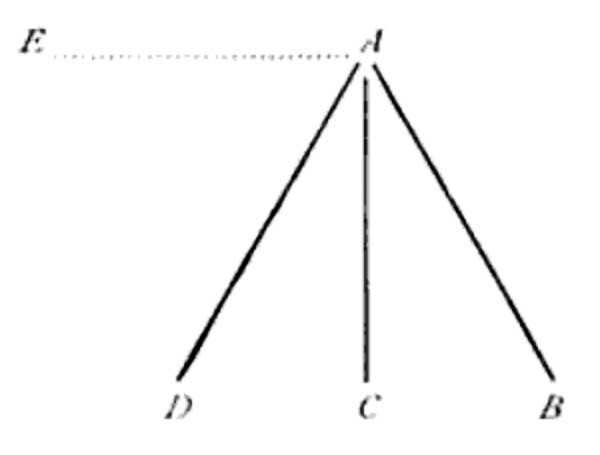

Returning from El Dorado County, where they had passed the winter of 1856-'57 in prospecting for quartz lodes without success, they revisited Gold Cañon in the spring of 1857. On the 8th of June, 1857, Allen wrote: "We struck the vein (in Gold Cañon) without difficulty, but find some in tracing it. We have followed two shoots down the hill, have a third traced positively, and feel pretty sure that there is a fourth. The two shoots we have traced give strong evidence of big surface veins. The following is a diagram of the set of veins:

"A seems to be the center from which all seem to radiate; B we have traced by boulders; C we have struck the end of; D the same; E is uncertain, though the evidence of its existence is tolerably strong; BAC may be the true vein and the shoots; DAE may be superficial spurs. We have pounded up some of each variety of rock and set it to work by the Mexican process."

"The rock of the vein looks beautiful, is very soft, and will work remarkably easy. The show of metallic silver produced by exploding it in damp gunpowder is very promising. This is the only test that we have yet applied. The rock is iron, and its colors are violet-blue, indigo-blue, blue-black, and greenish-black. It differs very much from that in the Frank vein, the vein we discovered last fall. The Frank vein will require considerable capital to start. The rock is very hard and the vein very much split up. The present vein lies very compact as far as we have examined it; not a leaf of foreign rock in it."

August 16, 1857, Allen wrote again from Gold Cañon: "Our first assay was one-half ounce of rock; the result was $3,500 of silver to the ton, by hurried assay, which was altogether too much of a good thing. *** We assayed a small quantity of rock by cupellation from another vein. The result was $200 per ton. We have several other veins which are as yet untouched. We are very sanguine of ultimate success."

During the summer of 1857, as during the previous years, the brothers supported themselves by washing the cañon sands for gold while prospecting industriously for veins of silver ore. They made no attempt to develop any of their discoveries, except by examining the intervals between jutting boulders in order to trace the lines of surface croppings, for they had no money and knew that it was impossible to open a vein properly without capital.

Their claims were fairly productive, but several hundred yards distant from the cañon creek, so that they were obliged to transport the dirt in sacks to the water, and this labor consumed so much working time, which they were anxious to devote to their search for silver, that they washed only enough sand to pay for their food.

Placer washing was merely a needful drudgery. The search for hidden veins of ore has an indescribable fascination, which beguiles and holds fast the most stolid of men. The Grosh brothers, ardent and ambitious, grudged themselves the necessary food and rest, and would fain have spent every moment in rock chipping and assaying.

Their brightening prospects of success goaded them to impossible exertions; for as soon as they should succeed in determining the existence and course of a rich ore-bearing ledge, they were promised the money requisite to develop it by George Brown, a cattle-trader of Carson Valley.

The "black rock," which assayed $3,500 to the ton, “presented so many difficulties," wrote Alien, September 11, 1857, "that we lost our patience, and, relying on Brown, we dropped everything, determined to master it. The very day we had determined it we heard the first news of his murder."

Fortune had again disappointed them, but the brothers did not lose heart. Mrs. L. M. Dettenrieder, who had faith in the men and their work, promised to assist them with money which she had saved, and they planned also to secure the help of some enterprising capitalist in California.

Whether they would have succeeded in this endeavor, and whether their seven years of persistent toil would have been crowned with reward, can never be known.