The Slate Creek district is located in Whatcom County, Washington. The following overview is part of the 1969 publication Mines and Minerals of Whatcom County, Washington by the Washington Department of Natural Resources, Division of Mines & Geology.

The Slate Creek mining district is in the eastern part of Whatcom County and extends from longitude 121° eastward to the Whatcom-Okanogan County line. The Canadian border is the northern boundary for the district, and the Skagit County line forms the southern boundary. (About 20 percent of the Slate Creek mining district is in Skagit County, but that part is not discussed in this report.) The entire district is in the Mount Baker National Forest, and the greater part of it is in the North Cascade Primitive Area. Prior to 1893 the district was known as the Ruby Creek and Canyon Creek mining districts.

Mining History

Although placer mining had been carried on in the Slate Creek district since the 1870's, the main rush to the district did not take place until 1894-the year following the discovery of the Eureka lode by A. M. Barron. Upon the discovery of free-milling gold ore at the surface, trails were opened into the district from the Skagit River on the west and from the Methow River on the east in Okanogan County. Prospectors rushed into the district, and the mining camp of Vera Cruz sprang up near the site of the new gold discovery.

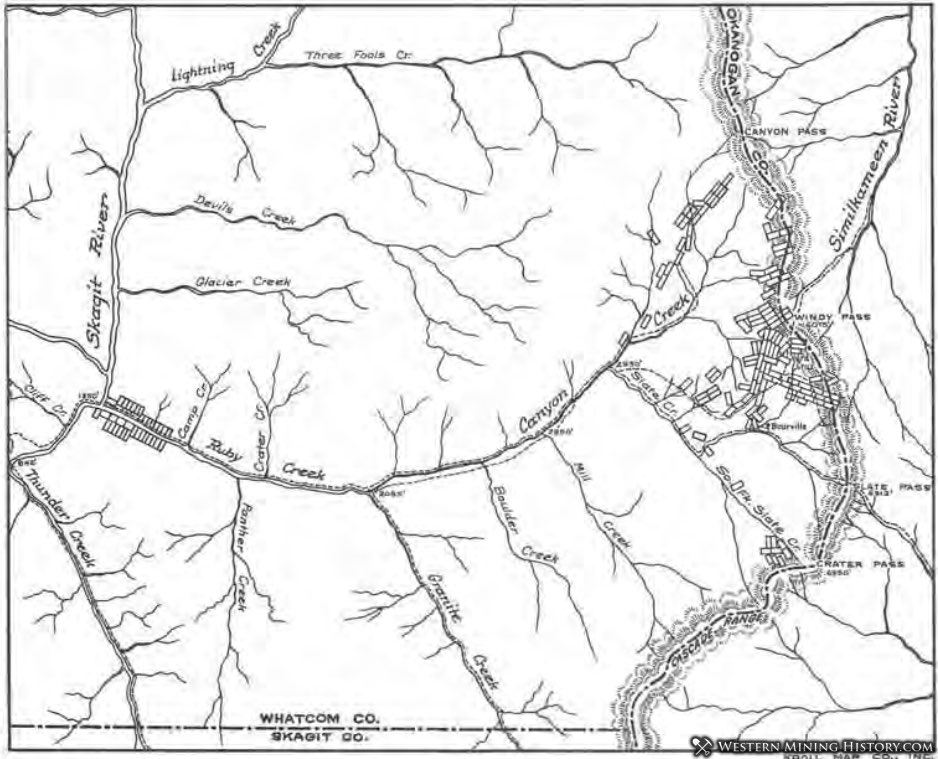

In 1896 a stamp mill was erected on the west bank of Bonita Creek, and by means of a surface tramway the ore was conveyed from the mine high on the mountainside to the mill at creek level. During 2 years' operation, $120,000 in gold was produced from the "Glory Hole" on the Eureka claim, but operations ceased when the gold values declined. By 1898 most of the area, which was then known as Eureka Gulch, had been staked and adits were being driven on many quartz veins. A map of the mining district as it was in 1899 is shown in Figure 37.

The Mammoth vein, which is about a mile southeast of the Eureka lode, also proved to be rich in gold, and a stamp mill was built on the property. From 1898 to 1901 about $397,000 in gold was produced from this mine. By 1900 the gold rush had subsided and most properties were abandoned. Many prospectors left the area for the Alaskan gold rush of 1898, and others were discouraged when it became apparent that the free-milling gold ore gave way to base metals at depth. Others were discouraged when mining experts said that the ore was too low in grade for treatment and that it would be impossible to follow the veins for any distance because of their faulted nature.

However, optimism still prevailed at several properties, and stamp mills were constructed at the Goat, North American, Minnesota, and Anacortes mines. Amalgamation was the principal means of recovering gold, and only the richest gold ores could be worked profitably. At several mills the ores were treated by unskilled millmen, and therefore in some instances the gold recovery was less than 50 percent. Trails were still the only means of access, and all equipment and supplies were packed to the mines on horses. However, from Ventura, which was at the confluence of the Methow River and Lost River, a narrow-gauge (26 inches wide) wagon road led as far west as Harts Pass; around 1903 the road was widened to 36 inches and was extended to Barron.

Around 1900 the mining camp of Barron, named after A. M. Barron, who had discovered the Eureka lode, was established on Bonita Creek downstream from the Eureka mill, but a few years later the town-site was relocated a short distance east of Bonita Creek near its junction with Slate Creek. The settlement consisted of a store and a tavern that supplied the basic needs of several hundred prospectors, whose tents dotted the landscape. A miner's wages were then $2.50 for a 10-hour day. It was near here that the second Mammoth mill was built in 1905, the remains of which are still visible from the Slate Creek road.

Also in 1905, the Chancellor Mining Co. built a powerplant at the confluence of Slate and Canyon Creeks. Electricity generated by the plant was used by the Bonita Gold Mining Co., which was mining and milling ore from the Eureka lode. Mining was also undertaken at the Tacoma, Goat, Indiana, and Illinois mines, and at mines in Allen Basin; all mines were within a few miles of Barron. Seven miles west of Barron, near the confluence of Canyon and Mill Creeks, the North American Mining Co. built a stamp mill in 1907; and at the Minnesota mine, on Canyon Creek a short distance downstream from Mill Creek, another stamp mill was built in 1908 by the Seattle-St. Louis Mining Co.

In 1915 new interest was shown in the area when it was rumored that a railroad was to be built up the Methow River to serve the district. In 1916 the financing for the Methow Valley Railroad began, but the project was soon abandoned. It was about this time that C. R. McLean, H. J. Ballard, and C. R. Ballard located the Azurite group of claims near the head-waters of Mill Creek. The Azurite Copper Co. was formed, mainly with the backing of eastern money, and exploration work was started on the claims.

In 1925 the company was reorganized as the Azurite Gold Co. Work at the claims was expensive, because mining supplies had to be packed on horses 24 miles from the Methow River at a cost of $100 per ton. The company constructed a narrow-gauge road to the mine in 1930. After 18 inches had been cut off the axles of trucks, they were able to negotiate the steep mountain road. A small smelter was erected at the property, but it proved to be inefficient. However, a few tons of copper matte from smelting operations was shipped to the Tacoma smelter in 1933.

In 1932 a religious group moved into the district and established a colony in the vicinity of the Tacoma and Mammoth mines. Several sturdy log buildings were erected by the group, who had hoped to build a sawmill and operate the mines. However, after much difficulty, the squatters were persuaded by the legal claim owners and officials of the Forest Service that they were trespassing. By 1934 the last of the group had left the district.

In 1934 the price of gold rose from $20.67 per ounce to $35 and, as would be expected, there was renewed interest in the gold possibilities of the district. The American Smelting and Refining Co. acquired a 25- year lease on the Azurite mine and began extensive development work as well as construction of a 100-ton cyanide plant. The narrow-gauge road to Barron was rebuilt in 1935 by the Forest Service to accommodate conventional vehicles, and on Bonita Creek a new mill was constructed by the New Light Gold Mining Co. to treat gold ore from the Eureka lode (Fig. 44, on p. 116-117). The Azurite mill was put into operation in 1936 and operated continually until 1939; during this time the mine produced $972,000 in gold.

About 1.25 miles west of the Azurite mine, on a tributary to Granite Creek, the Gold Hill Operating Co. began development on several promising lead-silver veins. At the Eureka lode, mining and milling was undertaken on a small scale.

In 1942, Government War Order L-208 closed all gold mining operations in the United States; this order marked the end of major gold milling operations in the Slate Creek mining district.

In 1946, after the end of World War II, gold mining restrictions were lifted. In 1947, Western Gold Mining, Inc., which had acquired the Eureka property in 1940, mined and milled several hundred tons of gold ore from the Eureka lode, mainly for test purposes. However, full-scale mining operations were not resumed. At the Golden Arrow mine, on the Tacoma claim, small-scale mining operations were undertaken and shipments of gold-silver ore were made to the Tacoma smelter in 1951, 1952, and 1953. These shipments of ore were probably the last to be made from the district. At present (1966), the most active mining company in the district is Western Gold Mining, Inc. Although it is not in production, development and exploration work is carried out on its claims, which contain the original Eureka lode. A 120-ton gold mill is kept in a state of readiness for the day operations can be resumed.

In all, 2,812 claims were staked in the Slate Creek mining district from 1894 to 1937. The breakdown for the number of claims in different parts of the district is as follows: Slate Creek, 1,628; Canyon Creek, 405; Ruby Creek, 455; Mill Creek, 245; Granite Creek, 68; and Panther Creek, 11. Of these claims, 52 were granted patents, but the two major gold producers of the district, the Azurite and the Eureka, were never patented. Although most prospectors did not realize much in the way of monetary reward for their efforts, to them goes the credit for building most of the trails and roads that made the area accessible. Only at a much later date did the Forest Service begin to main- tain the trails and roads.

Placer mining has been carried on in the district since the late 1870's, but the operations have been small and sporadic. Credit for the discovery of placer gold is given to a man named Rowley. At Rowley Chasm on Ruby Creek-about three-quarters of a mile downstream from Boulder Creek-Rowley discovered coarse gold nuggets in the south bank of Ruby Creek. As a result of his discovery, over $100,000 in gold was supposed to have been recovered by Rowley and other prospectors. At that time, access to the area was from Fort Hope, in British Columbia. From Fort Hope a trail led down the Sumallo River to the Skagit River, from which point an Indian trail extended to the mouth of Ruby Creek.

Because of the inaccessibility of the area, only the rich bars were worked and then abandoned. In June 1891, Henry Benke and Hilmar Jacobson made discoveries of placer gold on Slate Creek "about 6 miles up from Canyon Creek." This discovery was followed by a general rush of prospectors to Ruby and Slate Creeks that resulted in the staking of many placer claims. Around 1895 the Old Discovery claims were being worked near the site of Rowley's original discovery and the Ruby Hydraulic Gold Mining Co. began operations on the Scougale claims at the mouth of Ruby Creek. Placer operations on Ruby, Slate, and Canyon Creeks continued on a small scale until around 1914. By that time only two placer deposits were still operating; the most active operation was that of the Granite Creek Mining Co., whose operations were on Slate Creek.

It was not until the depression years of the 1930's that operations began once again in the district. By 1939 at least five placer mines were in operation on Ruby Creek, but production was insignificant. The total production in 1939, as reported by sales to the U.S. Mint, was only 22 ounces. Although placer mining ceased in 1941, a few individuals still pan gold along Ruby, Canyon, and Slate Creeks during summer months.