Camp Bird District (aka Imogene Basin District)

The Camp Bird Mine is considered by some as its own district. Hill (1912) used this name for the Imogene Basin District. Vanderwilt (1947) named the Camp Bird the most famous mine of the Sneffels District. He pointed out that, while the main feature of the Camp Bird Mine was its gold, the mill was redesigned in 1942 to recover zinc for the war effort. An additional reference is Dunn (2003).

Ransome (1901) discussed the Camp Bird Mine in his section on the lodes of Canyon Creek. He described the large Camp Bird vein as crossing the head of the Imogene Basin at N80W, with a dip averaging 70o S. It was traced into the Marshall Basin to the west and possibly is equivalent to the Pandora lode in the Telluride Quadrangle.

Eberhart (1969) relates a tale of Thomas Walsh, who made his fortune on the Camp Bird Mine. It was discovered, maybe by Walsh himself or by a prospector Walsh hired, in 1896 by recognizing rich ore on the dumps of the Ura and Gertrude Claims. Walsh subsequently purchased most of the claims in the basin and ended up making the Camp Bird the largest producer of gold outside Cripple Creek.

The mine itself is truly famous. Rosemeyer (1990) featured the history and minerals of the mine in Rocks and Minerals Magazine.

Ransome (1901) describes the vein as occurring in an andesite breccia of the San Juan Formation. It is mostly massive quartz (Moore, 2004), ranging from 5 to 10 feet thick with numerous ore shoots in and around it. The richest gold-bearing zone averaged 1.4 oz. gold and 2 oz. silver per ton.

Engineer Mountain District

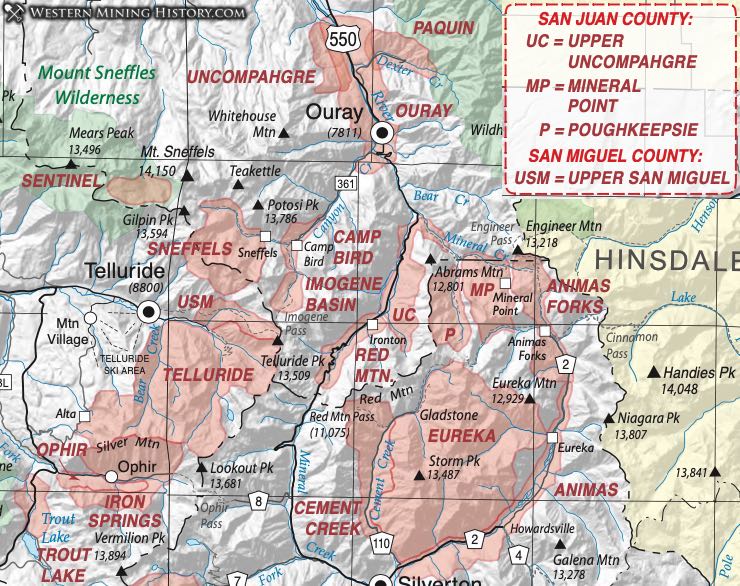

The Engineer Mountain District lies where Ouray, San Juan and Hinsdale Counties meet and is surrounded by several other districts - the Poughkeepsie, the Mineral Point, the Galena, and the Eureka. It was recognized as a separate district by Moore (2004). Mindat.org includes the Engineer Mountain area in the Ouray District. Burbank and Luedke (1969) appear to include the Engineer Mountain area in the Eureka District while King and Allsman (1950) include the area within the Mineral Point District.

Moore (Ibid) defines the area as bounded by Mineral Creek on the south, extending north of Engineer Mountain "about a mile" and as far east as Henson Creek in Hinsdale County. Thus, he defines it as including mines in all three counties in the headwaters of the Animas, Uncompahgre, and Lake Fork Rivers.

Mindat.org includes the Bismuth and Uncle Sam Mines, but they appear in no other sources. The Bismuth Mine was a former Au-Ag mine located 1.7 km (1.0 mile) northwest of Engineer Mountain. The Uncle Sam Mine was a former Au-Zn-Ag-Pb-Cu mine located 0.5 km (0.3 mile) southeast of Engineer Mountain, on National Forest land. Hon et al. (1986) list the Frank Hough, Polar Star, Palmetto, Engineer and Wyoming mines.

The geology and mineralization are the same as in the other districts listed above, as part of the vein complex of the Silverton Caldera.

Poughkeepsie District

Another of the several historical districts grouped together around the Silverton Caldera is the Poughkeepsie (or Poughkeepsie Gulch) District. The Poughkeepsie District spans the county line and actually much of its area is in San Juan County. Mindat.org (2015) lists the Poughkeepsie Gulch District as being in the Red Mountain District in San Juan County.

Henderson (1926) does not mention the district in his list, but describes development in Poughkeepsie Gulch in his narrative. Vanderwilt (1947) includes the district in a descriptive section by Burbank and appears to account the district in San Juan County. Therein, Burbank describes the district as adjoining the Mineral Point and Upper Uncompahgre District at the headwaters of the Uncompahgre and Animas Rivers, thus surrounding the main stem of the Uncompahgre River, extending into San Juan County nearly to Hurricane Peak.

Moore (2004) describes the extent of the district from the confluence of the Uncompahgre River with Red Mountain Creek, up the main branch of Poughkeepsie Gulch south to Hurricane Peak in San Juan County to include the area around Lake Como.

The geology of the area is characterized by a basement of tightly-folded Precambrian quartzite and slate seen in the canyon of the Uncompahgre River. West of the river some Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimentary rocks occur between the Precambrian and the overlying Tertiary volcanics. In Poughkeepsie Gulch most of those volcanics are latite and rhyolite flows, tuffs and breccias of the Silverton volcanic series underlain with varying thicknesses of the San Juan tuff.

Mineralization occurs in swarms of veins extending out of the Silverton Caldera. Burbank (1947) describes three types of deposits: fissure and cavity fillings, breccia chimneys and dikes, and replacement deposits. Most of the productive veins are in rocks of the Silverton series, although some occur in the San Juan Tuff and the Precambrian quartzite beneath.

Output described by Vanderwilt and Burbank (1947) and Hazen (1949) occurring from 1874 to 1941 is estimated at $2M of silver, gold, lead, copper and zinc. Most of that came before 1900 and from 12-15 of the largest mines. Of note is the Old Lout Mine, described in some detail by Burbank and Luedke (1969). Most of the mines went inactive after 1900. The exception is the Mountain Monarch which continued producing as late as 1946. All the authors feel that much ore remains. Because of the difficult mining conditions, most activity ceased after the high-grade material was depleted.

Eberhart (1969) talks of the tough of Poughkeepsie, 76 miles south of Ouray and twelve miles up Cement Creek from Silverton. At one time, the town boasted 250 residents (summer residents, at least) along with stores, restaurants, saloons and a post office. Henderson (Ibid) describes the completion of a road up Cement Creek from Silverton in 1879 to the head of the Poughkeepsie Gulch. Activity was already on- going in the Gulch at claims including the Old Lout, the Poughkeepsie, Alabama, Red Roger, Saxon, Alaska, Bonanza, and others.

Red Mountain District

The Red Mountain District was recognized by Henderson (1926), who noted that the district over lapped the Sneffels and Uncompaghre (Ouray) Districts. Vanderwilt (1947) also recognized the district and Burbank included a description in the classic 1947 volume on Mineral Resources of Colorado. Dunn (2003) points out that the Red Mountain was one of the original six districts defined in 1882 for Ouray County, of which the Mount Sneffels (Sneffels) and Uncompahgre (Ouray) are still in Ouray County (while the other three lie in later-established counties.)

Moore (2004) defines the geography of the district. He says it extends across the county line to the headwaters of Mineral Creek in San Juan County (over Red Mountain Pass). Its extends from the northern end of Ironton Park south to the three Red Mountains (#1, #2, and #3) and Mount Abram and west to the divide above Red Mountain Creek. The mineralization is the same as - and continuous with - those of the Telluride and Sneffels Districts.

The area lies on the northwest rim of the Silverton caldera in a marginal zone of ring faults. Some older rocks of the Ouray and Leadville limestones and the Hermosa Formation crop out in the Ironton Basin, but further south they are mainly the Silverton volcanic series with the San Juan tuff on the west side of the district. The most productive mines lie in a zone about a mile wide and four miles long.

Most of the districts production came from chimney-like ore bodies in or near breccia pipes and volcanic plugs, filling open spaces and caves or replacing altered wall rock (Burbank, 1941; 1947). Burbank describes some nearly solid copper-silver sulfide bodies. Copper is more abundant than is typical in the area (and in fact in Colorado), and many veins contained massive bodies of lead and zinc sulfides.

The district was being thoroughly explored by the 1870s. The earliest discovery in the area was in San Juan County in 1881. Production declined significantly by 1900, with later bursts of activity during the two world wars. During the district's heyday some of the large mines spawned development of vibrant (but short-lived) settlements such as Red Mountain Town, Guston, Old Congress Town and Ironton. Eberhart's classic book on Colorado Mining Camps (1969) contains some stories about those early towns.

Sneffels District (aka Mount Sneffels District; includes Imogene Basin District, Camp Bird District)

The area of the Sneffels District is on the northwest edge of the Silverton caldera. The geology and geographic location of the district generates confusion with district names. The districts of Imogene Basin, Camp Bird and Telluride are often associated with Sneffels District, not to mention the alternate name of Mount Sneffels District.

Burbank (1947) points out that the general San Miguel "mining area" (quotes mine) encompasses some 250 square miles in Ouray, San Miguel and San Juan counties around the headwaters of the San Miguel, Uncompahgre and Animas Rivers. Within that area is the Sneffels District.

Henderson (1926) called the Sneffels District Mount Sneffels and located it in T43N, R8W, but extending south into sections 1 and 2 of T42N R8W. (That southern extension would project into the Red Mountain District of our map.) Vanderwilt (1947) refers to it as the Imogene Basin District. In that same volume, Burbank points out that the Sneffels and the Telluride Districts are one and the same, with the name changing at the Continental Divide.

Burbank, in his 1943 report on the Uncompahgre District, speaks of the Sneffels with the Telluride District as one, as does Moore (2003). Fisher (1990) breaks out the Camp Bird as sort of a sub-district, but also combines the Sneffels-Telluride into one.

Mindat.org is less definitive. The website lists the Mount Sneffels District, but also lists the Sneffels as the Red Mountain District (inconsistent with this report) and Mount Sneffels, but includes the Camp Bird Mine within that district (as we do.) Both Sneffels and Camp Bird are listed under the Ouray District.

The stratigraphic section of the area contains rocks as old as the Pennsylvanian Hermosa Formation, deposited prior to the Uncompahgre uplift, lying on Middle and Late Proterozoic quartzites (Fisher, Ibid). Unconformable above that Paleozoic-Mesozoic sequence is the Tertiary Telluride conglomerate and some 1000 meters of flows, tuffs, breccias and mudflows. At the base of the volcanic-related sequence is the San Juan tuff - 700 meters of intermediate-composition volcanics and volcaniclastic sediments, mudflows, lava flows and flow breccias of 30-35Ma age. Structure is dominated by northwest-trending dikes, fissures, and veins radiating from the Silverton Caldera.

Moore (Ibid) recognized several stages of mineralization - early quartz veins with base-metal sulfides, quartz or quartz-carbonate veins with gold and silver, and late barren veins. Most of the mines occur in the San Juan tuff, although a few are found in the units directly above or below that unit.

Burbank (1947) discussed the Liberty Bell Mine (in the Telluride District) and the Camp Bird. The latter was operated from 1896 to 1916 for gold and silver, then again from 1926 with the recovery of lead. Zinc recovery began in 1942. He points out the interesting situation with the Treasury Tunnel. That structure extended beneath the continental divide from Ouray County to the Black Bear Mine in San Miguel County. Production was attributed to San Miguel County, although the portal and the mill were both in Ouray County. Lead, copper and zinc were recovered primarily from veins in the tuff. Bastin (1923) adds considerable information on mineralization in the combined Sneffels-Telluride Districts.

The Camp Bird is commonly treated as a special case (e.g. Moore, Ibid), and is discussed in detail in Spurr (1925). The entry on mindat.org for the Camp Bird Mine is notable for an extensive list of references, which will not all be included here. The mine has produced intermittently since 1896 and was reportedly under further development in 2015. The story of the mine's discovery and the development of the settlement is found in Eberhart (1969).

Upper Uncompahgre District

The Upper Uncompahgre District is not listed in Henderson (1926), but is considered by Vanderwilt (1947) to be synonymous with the Uncompahgre District. Within Vanderwilt's volume is a description by Burbank of the Uncompahgre and Ouray Districts. Dunn (2003) lists the district separately as adjoining the Mineral Point and Poughkeepsie Districts, including the headwaters of both the Uncompahgre and Animas Rivers in Ouray and San Juan Counties. Mindat.org (2015) does not list the Upper Uncompahgre, but puts it in the Eureka District (of San Juan County).

Moore (2004) provides a significant amount of information, as provided here. First, he describes the district's location in detail as "the area around Bear Creek Falls to the north end of Ironton Park, including the canyon of the Uncompahgre to the junction of Red Mountain Creek and continuing up the canyon along Red Mountain Creek. The western flank of Mt Abram and the drainages into Red Mountain Creek from Hayden Mountain north of Ironton Park form the southern part of the district."

Summarized by Moore (2004), the geology of the district consists of tightly-folded Precambrian quartzite and slate in the canyon of the Uncompahgre with a wedge of Paleozoic and Mesozoic sediments on top below volcanics. The mountain slopes are primarily San Juan Tuff (up to 2,500 feet thick), thinning toward Poughkeepsie Gulch. In that tuff lie the most productive veins, according to Burbank (1947). Ore deposits occur as fissure and cavity fillings, breccia-chimney and breccia-dike deposits and some replacement deposits.

Kelley (1946) points out that the radial faults of the Silverton Caldera do not occur here. The ore veins of the Dunmore, Columbus, Thistledown, Chapman and Ores&Metals are fissure veins in tension fractures. Additional references include: Hazen (1949), Irving (1905), and King and Allsman (1950).