This is a limited time preview of members only content. For information on memberships at Western Mining History, see our memberships page.

By Eliot Lord

From Volume 12 of The New England Magazine, published in 1895

There are few American school-boys who cannot tell the story of the chance discovery of the glittering specks in the sluice-way which made a golden image of the great West. The gold of California revealed itself unsought; it was a gift from the open hand of Fortune. But the silver of the great West was held fast in a clinched hand; it was painfully sought and painfully gained. The story of its discovery is known to few even in barest outline. Yet it forms one of the most memorable scenes in the drama of industry.

In the days of the Argonauts of ‘49, two brothers joined the swarm that braved the dragon danger in every form for the fleece of the new El Dorado. They were the sons of a Universalist clergyman of Reading, Pennsylvania. Ethan Allen Grosh was twenty-four years old, and his brother, Hosea Ballou Grosh, twenty-two, when they sailed from Philadelphia with a company of gold-hunters, on the twenty-eighth of February, 1849. They were closely alike in body and mind. Both were a trifle under middle height, with well-knit, compact figures. Their faces were fresh-colored and somewhat freckled, their eyes light blue, and their hair light brown. Light curling beards covered their faces with a rather straggling growth. There was nothing in their appearance to mark them; but the stuff of which heroes are made outside of romance has often no surface show.

Their chances of success seemed uncommonly bright. Others were young, strong and hardy like them, but few of their companions were so observant, industrious and temperate. They were students and knew something at least of elementary chemistry and mineralogy; their pluck was unfailing; they were light-hearted in face of every discouragement; their bearing was modest, simple and sincere; they were honorable in all things; they were ready to help any who needed help. So they won general goodwill and respect, though they were somewhat reserved in disposition and confided in few intimate friends. The companion who knew them best has written of them that “they were in truth religious, not apt to talk about it, not wedded to any special dogma, but filled with that genuine religion of the heart which is the salt of the earth, and which keeps whoever possesses it, as it kept them, fearless, earnest and pure.”

The ship which bore them was bound for Tampico, Mexico. On the way a storm struck it, driving it many leagues back and out of its course. At the height of the storm a bolt of lightning shivered a mast. For hours there was deadly peril of foundering, but the shattered ship bore up stubbornly, and after a month at sea reached port in safety with its freight of Argonauts. No omen and no danger weighed down the buoyant hearts of the brothers.

After landing came the vexation and perils of the journey across Mexico. The route was misjudged. The roads were bad, and in places there were no roads. The travelers plodded along painfully. The tropic sun glared on them. Water failed them; what little they could find was usually nauseous and foul. The country in sight was barren and almost treeless. Provisions were poor and grudgingly sold at extortionate prices, if supplied at all. The natives watched the march with unconcealed ill-will, and barely refrained from attack. Pestiferous insects worried them day and night, and insults were nearly as thick as the fleas. Their horses and mules, inflamed by thirst and hunger, were continually straying away and often were scattered by malicious stampedes. With the catalogue of plagues came malarial fever and dysentery to prostrate more than one-half of the party, and among them the young adventurer, Hosea Grosh.

This was tough enough to turn the stomach of any Mark Tapley; but this was not all. As a final buffet, the contractor who had agreed to transport them to California and had been paid in advance sent word that he could do no more, when the party was still eighty miles from the west Mexican coast. Luckily for him not even their curses could reach him. The wretched Argonauts could not turn back if they would. To linger longer where they were was to die. There was nothing to do but to press on. It was a wasted and sickly remnant that straggled into San Blas after ninety days of tramping through Mexico.

The Grosh brothers were almost penniless, like the greater part of their companions; so they were left behind by the first steamer that touched at San Blas on its way to the Golden Gate. It was the cup of Tantalus to the gold seekers who stood on shore and watched its lingering trail of smoke. But they were not wholly without resource, for they had the hard-used teams of the defaulting contractor. The Grosh boys succeeded in selling their share of the mules and horses and pawning the wagons and harness for a steerage passage on the bark Olga, which sailed from San Blas on the twelfth of July.

It was a motley crowd that swarmed over the ship. A Babel of tongues prattled of gold from morning to night:-

“Gold! and gold! and gold without end! Gold to lay by, and gold to spend, Gold to give, and gold to lend, And reversions of gold in future.”

Even in sleep they babbled in visions of gold. All day long the fortune-hunters strained their eyes for a glimpse of the gilded shore, while a light wind fanned them slowly along the coast. Scarce one of them had ever handled a pick or a pan in actual washing or mining. Few of them had the faintest conception of the blank face of a placer and the baffling bars that lay in the way of the smallest pinch of gold dust. They would scarcely stoop for a nugget as small as a hen's egg. Their fancies were of a land of fairy tale, on whose winsome face were strewn gleaming lumps of virgin gold for the first comer to pick up if he could stagger away with his burden. The only preparation to which they bent was the cutting and sewing of sacks to fill as Aladdin did. There is no strain of fancy in this reminiscence. It is the black-and-white sketch of a looker-on.

Among the few whose wits were not overlaid with gold were the Grosh brothers. Hosea lay sick in his berth in the steerage, watched over by Allen with the wakeful care of a mother. They had a cheerful word and smile for all comers, and were kindly noticed by some; but the crowd was so carried away with its gold fever that it had only a passing look for the sick man and his watcher. It was a tedious passage, with light, baffling winds: but on the thirtieth of August the Olga reached the Golden Gate and dropped anchor off the shore of the half-crazed town of San Francisco. The brothers went ashore in the rush with the rest; but Hosea was still so sick that Allen put by all thought of a dash for the gold fields. While the other adventurers on the Olga, crew and all, streamed off to the placers, he stayed behind with his brother, turning his hand to anything that came up, till Hosea was able to take the field.

It was not till the summer of the following year that the brothers had paid the debts incurred by Hosea's long sickness, and at last reached the gold fields in El Dorado County. Here they worked for a season with moderate success. They cleared two thousand dollars above their expenses, but spent all their savings in diverting the current of a river in order to wash the sands of its old channel. Their money and time were wasted, for the bed proved almost barren. So in 1853 they concluded to try their luck on the other side of the Sierras, and joined the little body of placer washers on a creek flowing into the Carson River from the west.

Close by this creek the main stream of migration was flowing along the overland trail to California. The Carson in summer was the merest ribbon of water, with brinks of green, but it was lovely in the sight of all who came to it out of the scorching sand and stunted brush of the desert. The flagging cattle sniffed the water afar off and used to break away for it wildly, rushing breast deep into the current and plunging their heads half under, while they gulped down its sweet water. Men too would throw themselves in with the cattle and drink like them, slaking the thirst of throats parched and crusted with alkali. This valley was the last halting-place in front of the towering wall of the Sierra Nevada, the last bar in the way of the glittering fields of the El Dorado of fancy.

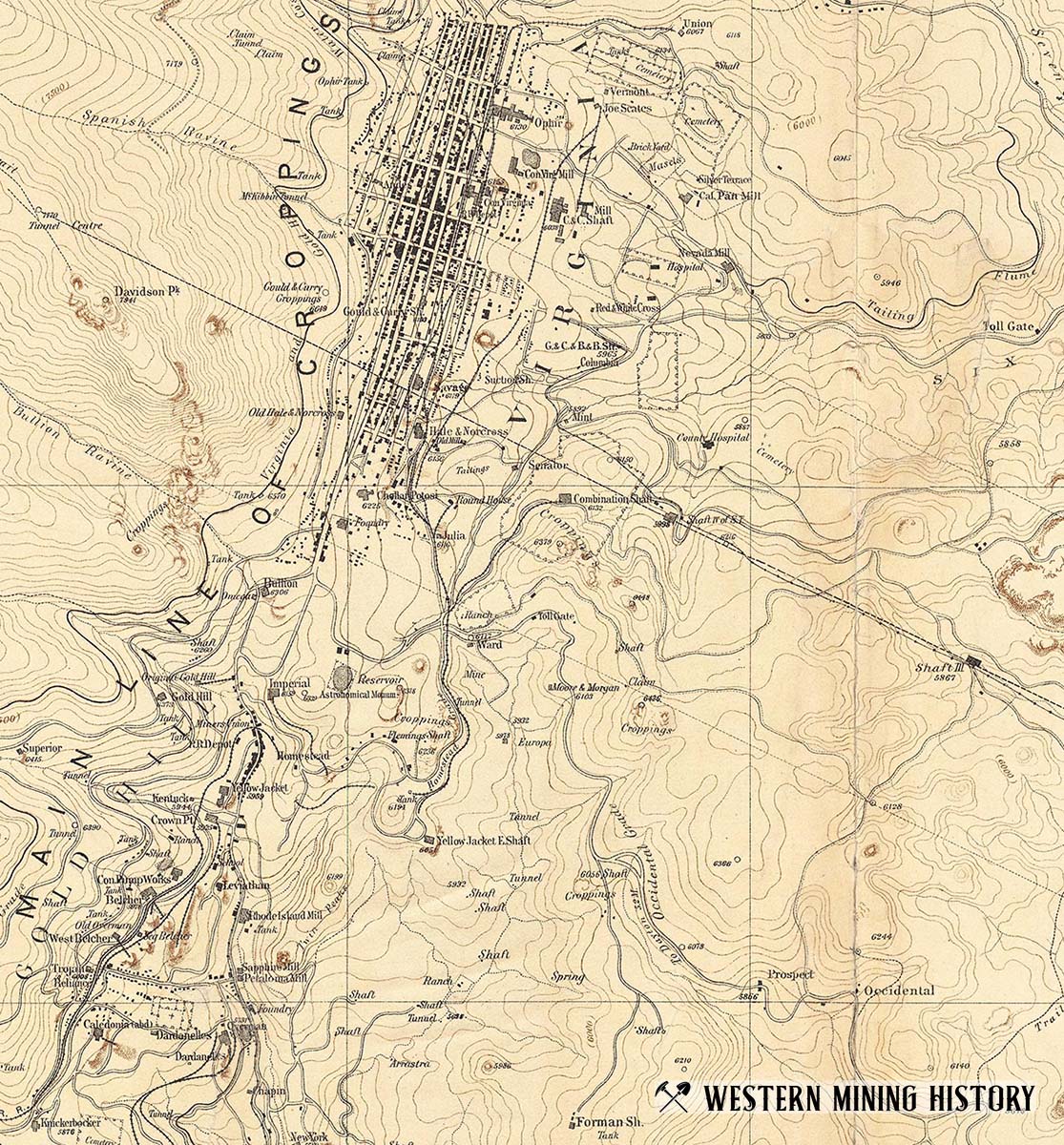

It is not strange that the gold hunters, who reached this oasis with minds fixed on the golden prospect beyond, had no eyes for the possible riches of the desert behind them. As they moved up the valley they looked up at the green and snow-tipped heights on their right in wonder and delight, but the barren fringe of hills on the left drew only a careless glance. There was a sprinkling of pine and cedar on it in patches, but for the most part a thin and ragged coat of sagebrush was the only cover of the ugly naked rocks that threw back the rays of the sun from their streaked, reddish brown faces. That repelling ridge was the last place to which a novice would turn for a deposit of treasure. But under that miser's cloak was hidden the mammoth store of silver ore renowned today as the Comstock Lode.

The first of the pioneer trains that entered the valley in the spring of the year 1850 was a company of Mormons, led by Thomas Orr. On the fifteenth of May it halted for a few hours at noon on the edge of a little creek that ran into the Carson from the bordering range on the east. While the women of the party were preparing the noon meal, one of the young men, William Prouse, washed a few panfuls of the creek sand, and showed his companions a trace of gold. The showing was not rich enough to divert any serious attention from the Californian goal, but the party was detained some days in the valley by the snow that blocked the passes of the mountains. While so waiting, John Orr, son of the leader, strolled up the creek with a companion. They reached a point where the walls of the cañon drew closely together and the creek ran between in little cascades. Here Orr pried off a fragment of rock with his butcher's knife from a crevice under the fall, and uncovered a little nugget of gold about as large as a walnut.

This was the first fragment of precious quartz taken from the first of the silver districts of the West; but Orr had not the faintest idea of the importance of his discovery, and kept the nugget simply as a pretty memento of his overland trip to California. When the first flurry of wild fancy had passed, some attention was paid to the humble little placer on the line of this creek; and in the early summer a few hundred workers were some-times strung out along the banks of the stream, dwindling in the fall of the year to a bare handful of washers as the creek shrunk to a thread.

It was to this summer colony that the Grosh brothers came in the year 1853, when they crossed the Sierras. None of the miners at work on the creek had troubled their heads by any speculation over the fountainhead of the gold dust which they washed from the sands. But the Grosh brothers knew that placer dust was only the surface crumbling from the ore that lay somewhere in veins in the hill range above. The gold of the placer only lifted their eyes to the hills in search of the veins.

Placer washing is a dull drudgery; but in the search for hidden veins of ore there is a continual fascination that tempts and masters the most stolid of men. There is something distinctive and great in the fever that burns in the veins of a prospector. It is not sodden avarice; it is not the curbed passion of a gambler at cards; it is the luring of fancy, the zest of the hunter, the thirst for discovery blending with grosser impulses in varying measure. No dangers daunt, no labors tire the men on the trail of the rock-bound bonanzas.

The Gold Cañon miners toiled in the usual way, with long-toms and rockers, washing the sand from the various bars and, when the richest placers were exhausted, carrying sacks and buckets of earth from the neighboring ravines to the nearest spring or to the creek itself. At nightfall they would return to their huts, cook their simple suppers of bacon and potatoes, with bread and tea, smoke a pipe or two, and then wrap themselves up in their blankets to sleep until daybreak. In summer most of the huts were merely heaps of brush rather inferior to the Pah Ute lodges. The winter cabins were usually of rough stones plastered with mud and covered with canvas, boards or sticks overlaid with earth. Sometimes holes were made in the walls for ventilation, but generally the cracks and open doorways were sufficient. Glass windows were an unthought of luxury. Some of the better cabins had simple iron stoves and funnels, but the majority of the miners were content with stone fireplaces and rude cranes.

A nondescript ball was sometimes given at one of the stations, but few of the miners succeeded in varying the staple amusements of gambling and drinking. On Sundays they rested—that is, “washed their clothes and cleaned up their cabins.” Some of them were fairly expert hunters, and used to supply their friends at times with a steak of antelope or mountain sheep shot on the neighboring hills. The ravines of the range were covered with a thick growth of small cedars, pines and underbrush, affording covert for deer and hares, game quite abundant till the Indians and miners thinned their numbers. Except when a supply of fresh meat was so obtained, the miners contented themselves with bacon or salt beef, purchased at the stations. Potatoes, almost the sole vegetable in demand, were purchased of ranchmen in the valleys.

While the others were plodding along day by day, the Grosh brothers devoted all the time they could spare from the narrow earning of bread to the search for ore veins. The gold dust of the creek was noticeably lighter than the dust of the California placers, and brought a dollar or two less per ounce. This vexed the miners at large, but they thought no more of it; while to the Grosh brothers it was the starting hint of the probable existence of silver-bearing quartz veins with the usual mixture of gold.

Up to that day there had been no determined search for silver in the country west of the Missouri. The Sonora Exploring and Mining Company, whose headquarters were in Tubac, had sent out a few explorers across the border, and some discoveries of veins were reported, but no effort was made to claim or develop them. The Grosh brothers were unquestionably the first persistent prospectors for silver in the great western field of North America. Let us follow their search.

In the autumn of 1854 the creek ran dry, and not even a bare living could be obtained from its placers. So the brothers recrossed the Sierras to California to prospect for gold quartz veins at Little Sugarloaf in El Dorado County. On the thirty-first of March, 1856, they wrote to their father in Pennsylvania: “Ever since our return from Utah we have been trying to get a couple of hundred dollars together for the purpose of making a careful examination of a silver-lead in Gold Cañon…. Native silver is found in Gold Cañon; it resembles sheet lead broken very fine, and lead the miners suppose it to be.... We found silver ore at the forks of the cañon. A large quartz vein shows itself in this situation.”

In September of the same year they had saved up the money needed, and crossed the mountains again to follow up their prospecting in Gold Cañon till the end of October. Then they returned to El Dorado County to renew their search for gold quartz veins. In a letter written on the third of November of this year they told of their success. “We found two veins of silver at the forks of Gold Cañon. . . . One of these veins is a perfect monster.” Again on the twenty-second of the same month they wrote: “We have hopes almost amounting to certainty of veins crossing the cañon at two other points.”Their winter prospecting in El Dorado County was fruitless, and in the spring of the following year, they went back to Gold Cañon, determined to develop their discoveries sufficiently to interest men of capital in their enterprise. On the eighth of June Allen Grosh wrote to his father: “We struck the vein [in Gold Cañon] without difficulty, but find some in tracing it. We have followed two shoots down the hill, have a third traced positively, and feel pretty sure that there is a fourth. The two shoots we have traced give strong evidence of big surface veins."

“We pounded up some of each variety of rock and set it to work by the Mexican process.... The rock of the vein looks beautiful, is very soft, and will work remarkably easy. The show of metallic silver produced by exploding it in damp gunpowder is very promising. This is the only test that we have yet applied. The rock is iron, and its colors are violet blue, indigo blue, blue black, and greenish black. It differs very much from that in the Frank vein, the vein we discovered last fall. The Frank vein will require considerable capital to start. The rock is very hard and the vein very much split up. The present vein lies very compact, so far as we have examined it; not a leaf of foreign rock in it.”

August 16, 1857, Allen wrote again from Gold Cañon: “Our first assay was one-half ounce of rock; the result was $3,500 of silver to the ton by hurried assay, which was altogether too much of a good thing. We assayed a small quantity of rock by cupellation from another vein. The result was $200 per ton. We have several other veins which are as yet untouched. We are very sanguine of ultimate success.”

It seemed indeed as if their patience and pluck through these weary years were at last to be crowned by signal success. They had kept their discoveries discreetly to themselves, and the miners at work on the creek paid only a flitting attention to the silent prospectors on the hills above them. But their keen search and unflagging industry had been marked by George Brown, a cattle trader of Carson Valley, and he had promised to put in the money needed to open up their silver quartz veins as soon as their location and prospective value were fairly determined.

On the very day when the brothers had reached their goal and Allen had sent off his letter, the news came to them of the murder of Brown by the Indians. The wife of one of the miners in the cañon, Mrs. L. M. Dittenrieder, went up to the cabin of the brothers on the hillside to tell them of the loss of their friend. It was a stroke from a clear sky, but the brothers bore it manfully and resolved to press on unaided until they could secure the help they sought. As Mrs. Dittenrieder stood at the door of their cabin, Allen pointed out to her, as she told me, the general location of one of his ledges on the eastern slope of the largest mountain of the range, later named Mount Davidson. She was an honest, straightforward woman, and there is no ground for impeaching her evidence. If she was not mistaken, there can be no doubt that the brothers had struck their picks on the crest of the heart of the great Comstock Lode, the biggest bonanza of modern silver mining. She had faith in them and the will to help them, but she could do little to carry them on.

Relying on Brown's assistance, they had dropped everything, as Allen said, in order to master the problem of the ledges. They worked on indomitably for three days longer, when they were called to face the bitterness of a parting which each dreaded more than death. Hosea was hard at work, when his foot slipped, and he struck the point of his pick into his ankle, inflicting a deep and painful wound. Allen carried him on his back to their cabin and laid him tenderly on his rude bed. He succeeded in stanching the flow of blood, and applied the best dressing to the wound which he could make. There was no surgeon or physician in all western Utah at the time, and no possibility of help except from the homely prescriptions of the miners. Allen hung over his brother day and night, and the rough men in the cañon gave all the help in their power, but the wound was past their healing. Gangrene set in, and after nearly two weeks of suffering borne with unwavering fortitude Hosea died. In his last conscious hour he raised his head a little to kiss his brother farewell. When he was too faint to speak, his lingering look told his forgetfulness of self and his deathless love.

Allen had borne every trial that had come to him without a whimper of failing heart; but the loss of his brother almost broke him down. A few days after his brother's death, he wrote to his father. He described Hosea's accident, illness, death and burial in that remote cañon of Utah, and then continued: “In the first burst of my sorrow I complained bitterly of the dispensation which deprived me of what I held most dear of all the world, and I thought it most hard that he should be called away just as we had fair hopes of realizing what we had labored for so hard for so many years. But when I reflected how well an up-right life had prepared him for the next and what a debt of gratitude I owe to God in blessing me for so many years with so dear a companion, I became calm and bowed my head in resignation.”

On September 11 he wrote again: “I feel very lonely and miss Hosea very much - so much that I am strongly tempted to abandon everything and leave the country forever, cowardly as such a course would be. But I shall go on. It is my duty, and I cannot bear to give anything up until I bring it to a conclusion. By Hosea's death you fall heir to his share in the enterprise. We have so far four veins. Three of these promise much.”

Allen Grosh had rare stuff in him. Duty was not merely his guiding star; he lived and moved and had his being in it. Heart-sick as he was, and anxious to press his discoveries, he would not stir a foot from the cañon until he had earned enough by patient ground-washing on his placer claim to pay every dollar of debt incurred by the expenses of his brother's sickness and burial. The sanguine prospector who would do what he did is one of a million. Though working from dawn to nightfall, he did not succeed in paying off all debts and getting together what he required for his return to California until the middle of November.

Every day increased the hazard of the crossing of the Sierras; but he put duty before danger as well as before fortune. He was not able to start till the twentieth of November, when he set out from Carson Valley with only one companion, a young Canadian prospector, Richard M. Bucke. The sky was clear when they started, but it clouded over as they climbed the eastern slope before they reached Lake Tahoe near the head of the Truckee River. A gathering storm in the Sierras is a fearful threat. Black death by hunger and cold hangs in the air. There is no escape by running forward or backward. Light courier pieces fly over the sky; then comes a surge of sullen masses overflowing the sun, till all the sky is a shroud and every peak a pillar of cloud. Pines shudder and moan in the fitful gusts that lead a witch dance with feathery flakes until the storm breaks with a continual roar of thunder and wind and hail and paralyzing flashes. Less thrilling but still more deadly is the storm in which there is no ray of light, when the snow is blinding, when the wind makes breathing a pain and palsies the flow of the blood, when the strongest men grope and stagger along until they break down in the snow and die, unless they can contrive some shelter and rest.

It was such a storm that swooped down on the two prospectors in Squaw Valley. They were driven to the cover of the tree, where they scraped a hole in the snow and painfully built a fire. This saved them from perishing with cold, but they were trapped in the snow. The storm raged for days and kept them crouching over their fire. They ate the food they took with them, and hunger began to gripe them. When the storm began to break away, they tried to push on over the trail, but it was so buried in snow that they could not trace it or follow it when they did find it.. Then they knew that they stood face to face with death in the snow. To stay where they were was the lingering death of starvation. It was no easier or safer to struggle back than to struggle on.

The only faint chance was to break their way out of the trap. They were nerved and strengthened by desperation. The little burro that carried their outfit could not scramble through the drifts, and must have been left behind in any event, but the starving men had no other resource for food. So they killed him and roasted as much of his flesh as they could carry through the snow. Then they set off to make their way somehow over the range. They scrambled along as best they could, always waist deep in snow, and sometimes across drifts many feet deep, dragging themselves on by bush tops and branches and jutting rocks. After gaining a few yards, they would sink down panting in the snow, until they had breath to renew the struggle. Only men climbing for life could have so strained on. It seemed a miracle of fortune to these crawling, floundering men. when they reached the summit at last.

It was the noon of the twenty-ninth of November, nine days after their start from the Carson Valley. The sky was clear, but the wind that swept the peaks on that bright day was deadly. No living creature could face it or bear it long. The gasping men reached the cover of the trees on the western slope in the nick of time, chilled to the heart. Their matches were wet and spoiled in the struggle through the snow, but after repeated trials they lighted a fire by a flash of powder from their guns and warmed themselves. A ray of hope cheered them to renew their struggle for life, but it was soon overcast. Another storm broke upon them. They had made rude snow-shoes by their fireside, but the snow was so soft that they could not use them. They tried to keep moving in spite of the storm, for delay was deadly, but they could not see a hundred yards before them, and soon lost their bearings completely. They were forced to come to a standstill, and tried to light a fire for the night. But their powder was damp and their gun was so wet and rusty that it could not be fired. Then they burrowed holes in the snow and lay under cover that night of the second of December.

The next morning they crawled out of their holes, and were able to struggle along, but they had eaten their last mouthful of food in their burrows. Their lives hung on the chance of reaching help before they were too weak to move. They toiled on painfully and slowly till they reached the middle fork of the American River, and then followed its course as closely as they could. Day followed day, and with every passing hour they grew fainter with hunger and weariness. But they could not find any inhabited cabin or even a muddy creek with a sign of miners at work. Both had fought for life with marvelous endurance and spirit, but their strength was almost gone, and they felt that they were doomed men.

The morning of the fifth of December came, the third day since they had tasted food, but there was no sign of promise to the starving men. They no longer felt hungry, but they had a horrible sinking feeling in the pit of the stomach,” which Bucke still remembers with a shudder. He was the stronger of the two, but Allen, as he writes, was “least inclined to give up.” “I was heart-sick that day, and proposed that we should lie down and die, but Allen would not listen to me. He said, 'No, we will keep going as long as we can.” There was no strain that could break that heart, but it was stayed by duty and not by hope. “That night,” says Bucke, “we made our bed in silence and lay down.”

The starving boy had strange visions. As he lay on his bed of snow, he sniffed the steam from a prince's kitchen, and saw before him a banquet table, on which he feasted to his heart's content. But in the morning he knew it was a dream and he was dying for the want of a bit of bread. The two fainting men were barely able to crawl along. “We went,” says Bucke, “almost as much on our hands and knees as on our feet.” Hope was dead, but they resolved to crawl on while they could move hand or foot. They were not afraid to die, but the thought of loved ones at home waiting vainly for them and brooding over the horrors of their clouded fate nerved them to drag their weak limbs through the snow. From break of day till noon they had crawled less than a mile. Their eyes were closing with overmastering faintness, when they heard the bark of a dog and saw a thin wreath of smoke in the air.

They had reached a little miners' outpost called, strangely enough, “The Last Chance.” They cried out faintly, and their call was heard. Rescue came, but it was too late. The kindly miners carried the two sinking men into their cabin and cared for them as well as they could. It was found that their feet were badly frozen and they could neither eat nor sleep.

Allen Grosh died on the twelfth day after reaching camp. Only a few months before he had written to his father: “Hosea and I had lived so much together, with and for each other, that it was our earnest desire that we might pass out of the world as we had passed through it, hand in hand.” This was their fortune. In death they were not divided.

Bucke's life was saved, but one of his feet was rudely amputated at the ankle joint, and a portion of the other cut off. He hobbled on crutches to the door of a friend in San Francisco, who arranged for his return home to Canada. He went to Europe a few years later to pursue studies of medicine, and became an expert of distinction in his specialty. He is now the superintendent of the Asylum for the Insane at London, in the Province of Ontario, Canada.

He had some general idea of the silver vein locations at Gold Cañon, but he knew nothing definitely of the extent of the discovery. No one except George Brown, the cattle trader, had been taken fully into the confidence of the brothers, and he died before them. The papers of Allen Grosh, which defined and recorded the claims, were lost in the terrible crossing of the Sierras. The secret of the bonanza was buried with the discoverers.