-

4. BENCH PLACERS

Bench placers are usually remnants of deposits formed during an earlier stage of stream development and left behind as the stream cuts downward. The abandoned segments, particularly those on the hillsides, are commonly referred to as "bench" gravels. Frequently there are two or more sets of benches in which case the miners refer to them as "high" benches and "low" benches. In California and elsewhere, most bench deposits were quickly found by the early miners who proceeded to work the richer bedrock streaks by primitive forms of underground mining. At the time these were referred to as "hill diggings." Following the development of hydraulic mining in the 1850's, many of the larger bench deposits were worked by hydraulicking and the smaller ones by ground sluicing. During the depression years of the 1930's, much of the so-called "sniper" milling was carried out on remnants of bench gravels and it should be noted that these hard-working individuals seldom recovered more than 25 or 30 cents per day. -

5. FLOOD GOLD DEPOSITS

As a rule, finely-divided gold travels long distances under flood conditions. This gold which can best be referred to by the miners' term of "flood gold", consists mostly of minute particles so small that it may take 1,000 to 5,000 colors to be worth 1 cent. With few exceptions such gold has proven economically unimportant. The mineral examiner should recognize the true nature of flood gold deposits so that he can guard against being misled by their seemingly-rich surface concentrations. -

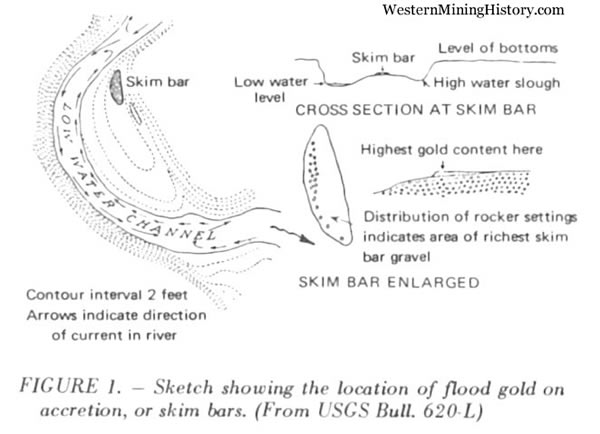

As a stream sweeps around a curve, the water is subject to tangential forces which cause a relative increase in velocity along the outer radius of the curve with a corresponsing decrease along the inside radius. The bottom layer of water is retarded by friction and as a result, it has a tendency to flow sideways along the bottom toward the inner bank. This, in turn, causes sand and small gravel to accumulate in the form of an accretion bar along the inside bank of the curve and where flood-borne particles of gold are being carried down the stream, some will be deposited near the upper point of such bars, as shown in Figure 1.

The foregoing is an oversimplification of a complex stream process but the fact is, in streams draining a gold-bearing region, seemingly rich deposits of fine-size gold may be concentrated near the upper point of the inside bars, between the high and low water marks. Good surface showings of fine-size gold are not uncommon and although they may appear to be valuable, experience has shown that in most cases the gravel a few inches beneath these surface concentrations is nearly worthless.

In many gold-producing areas, particularly in parts of South America, river bars have been skimmed by natives year after year from time immemorial. These are not permanently exhausted because floods deposit a new supply of gold and the renewal will continue indefinitely.

The best-known flood gold occurrences in the United States are found along a 400-mile stretch of the Snake River in western Wyoming and southern Idaho. Here they are called "skim bars" (Hill, 1916) and have been intermittently worked since about 1860. See Figure 1. They were first exploited by transient miners employing rockers and simple sluicing operations and, by cleaning up the richer spots, a few did fairly well. It was inevitable that some would proceed to install dredges or other large washing plants and launch ambitious mining schemes on the strength of surface showings. Needless to say, following the exhaustion of superficial pay streaks, most of these large-scale mining schemes proved unprofitable. The foregoing is pointed out because flood gold concentrations are still to be found and without doubt, new mining ventures will be proposed and attempted from time to time, particularly by advocates of suction dredges. The mineral examiner should learn to recognize flood gold deposits and equally important, he should be fully aware of their pitfalls. -

6. DESERT PLACERS

Desert placers in the Southwest occur under widely varying conditions but taken as a whole, they are so different from normal stream placers as to deserve a special classification. When dealing with the usual desert placer the mineral examiner must learn to disregard some of the rules of stream deposition, or at least, he must learn to apply them with caution. Desert placers are found in arid regions where erosion and transportation of debris depends largely on fast-rising streams that rush down gullies and dry washes following summer cloudbursts. During intervening periods, varying amounts of sand, gravel or side-hill detritus is carried in from the sides by lighter, intermittent rain wash which is sufficient to move material into the washes but not carry it further. When the next heavy rain comes, a torrential flow may sweep up all of the accumulated detrital fill, or only part of it, depending on intensity and duration of the storm and depth of fill. It should be obvious that the intermittent flows provide scant opportunity for effective sorting of the gravels or concentration of gold. Under such condtions the movement and concentration of placer gold will be extremely erratic. Moreover, where the entire bedload is not moved, any gold concentration resulting from a sudden water flow will be found at the bottom of the temporary channel existing at that time. This may be well above bedrock.

Desert miners have learned from experience that gold enrichments are sometimes found resting on caliche layers, particularly those near the ground surface, but such surface or near-surface concentrations are commonly small, residual-type accumulations of gold left behind where lighter material has been removed by rain wash and wind action. In other words, such enrichments result from the removal of valueless material rather than from the concentration of gold by normal stream processes. It should be stressed that in some desert placers the only economically minable ground is related to superficial concentrations and, at best, the chance of finding pay gravel is to a great extent fortuitous and largely dependent on careful prospecting.

Descriptions of many desert placer areas in the Southwest can be found in a number of publications among which are those published by the Arizona Bureau of Mines (Wilson and Fansett, 1961), the University of Nevada (Vanderburg, 1936) and the California Division of Mines (Haley, 1923, pp. 154-160).