3. SAMPLING METHODS

-

a. Existing exposures: During the early stage of a placer investigation a quick answer may be needed to determine if a significant expenditure of time or money is justified for further investigation. At this stage, practical considerations may limit initial testing to a few samples taken from existing exposures such as creek or dry wash banks, road cuts, old mining pits, etc. These can be informative if properly used.

Existing exposures are usually tested by panning, particularly where the exposure is small. In most cases the bedrock will not be exposed and the distribution of available sample points will be far from ideal and, in either event, it should be obvious that extreme care is needed when evaluating the sample results. On the other hand, the only preparation needed may he the cleaning away of sloughed or weathered material to expose fresh surfaces and, because of this, the use of existing exposures offers a cheap, fast method for preliminary testing.

By themselves, small samples obtained from existing exposures can seldom be expected to indicate the actual value of the ground. They may, however, prove or disprove the presence of gold and, if correctly interpreted, they can indicate the range of values to be expected. Nevertheless, many reports intended to prove or disprove the actual value of placer lands are based on a few pan-size samples taken from existing exposures and offered at face value. Such reports and sample data must always be viewed critically and accepted with reservation until proved valid. The very offering of this type of data, without qualification, may be good reason to question the expertness or intent of the vendor.

In brief, samples from existing exposures taken in conjunction with a placer investigation can, if properly evaluated, provide valid, useful data. But, for the inexperienced or the unwary sampler, existing exposures offer an inviting and sometimes unrecognized trap.

b. Hand-dug excavations: Hand-dug excavations in the form of pits, trenches or small shafts are generally suited to dry, shallow ground. They are most effectively used to depths of about 7 feet which is the depth from which material can readily be thrown with a shovel. Where practicable, they may provide the best means for sampling a placer. They generally do not require such close supervision as drilling nor do they require the high cost, specialized equipment or highly trained personnel needed for placer drilling. An extra bonus is offered by hand-dug excavations in cases where they remain open for some time, permitting resampling at a later date. In the case of dredge prospects, the principal point in favor of pits or shafts, where applicable, is the fact that they provide a much better idea of boulder content and gravel sizes than do small-diameter drill holes. Boulders are always an important factor in dredging operations.

The simple equipment needed for hand-dug sample pits or shafts is a particular advantage in remote areas or where only a limited amount of sampling is anticipated. A few strategically located pits or shafts may show that the ground is entirely unfit for mining or that it will not warrant the expense of drilling. On the other hand, if they return good prospects and the ground is subsequently drilled, the expense of preliminary hand work will be but a small part of the overall cost. Successful mining companies learned long ago to approach placer prospects cautiously and to make a few diagnostic tests before putting their money in an expensive sampling program. In many cases hand-dug excavations adapt well to this need.

The use of hand-dug shafts for general placer sampling was common practice at the turn of the century when labor was cheap and experienced shaft men were readily available but, today, because of the high cost of labor and a scarcity of experienced men, they are seldom used on a wide scale. But they may still be used to advantage in special situations; for example, by prospectors who expect to find good bedrock values in ground too deep for effective use of pits or trenches. In such cases one or more shafts will usually be put down to test the gravels lying on bedrock. This approach is common where the owner or a promoter's main concern is to convince someone that the property should be more thoroughly prospected by drilling or other means. Hand-dug shafts are commonly used to check selected churn drill holes and in many cases they are essential to correct interpretation of the overall drilling results. This is taken up in the section dealing with sampling by means of churn drills.

Most engineers agree that where feasible all of the material taken from a test pit or shaft should be washed. If the ground stands well and the walls of the excavation are cut square and parallel, it is an easy matter to determine the in-place volume of material removed and to directly compute its value after washing. An excellent description of a sampling program employing this procedure is found in an article by Sawyer (1932, pp. 381-383). The use of hand-dug shafts to prospect ground worked by the Wyandotte Gold Dredging Company of California has been described by Magee (1937, p. 186). Where an excavation cannot be measured accurately, it will be necessary to weigh the sample material or to measure its loose volume in a box or other container. In either case the indicated gold value will have to be converted to in-place or "bank" value by use of suitable conversion factors.

Where it is not practicable to wash all material, a good approximation of the ground's worth may be made by washing several pans per foot of depth as the excavation advances. But, this method is always risky unless the man in charge is completely impartial in his selection of material for panning and unless he is a trained placer sampler capable of applying experience-based judgement to the findings.

A somewhat similar procedure but one in which the personal factor is in part eliminated may be carried out as follows: Carefully deepen the pit or shaft in uniform, measured drops of say one foot at a time. Just prior to each deepening, carefully remove a sample by digging below the bottom of the pit or shaft to a depth exactly equalling the distance the bottom is to be dropped during the next deepening step. The minimum-size sample that can be conveniently taken in this manner will be one having a 12" x 12" cross section but if many rocks are present it may be somewhat larger. A sheet-iron caisson 18 or 24 inches in diameter by about 12 inches long can be used to advantage when the bottom sample must be taken from wet or ravelling ground. This type of sample may be taken from the center of the pit or shaft bottom or from any suitable Dlace but once started, its location should remain fixed. By following this procedure, a progressive sample can be obtained from undisturbed material ahead of the main excavation.

Where the excavation walls stand reasonably well, a sample can be obtained by cutting a vertical channel up one side of the pit or shaft. The excavated sample material can be allowed to fall on a canvas placed at the bottom of the pit or it may be caught in a bucket or box held close to the point of cutting. Where conditions permit taking a true channel, the sample volume can be determined by direct measurement but in any case it is best to weigh each sample as a check.

The first step in channel sampling is to clear away all foreign material from the ground surface above the place to be sampled. Next, thoroughly clean the sample area by scaling down the face to be cut. Following this, remove any loose material from the bottom of the pit where it might interfere with the sampling operation and, finally, check the bottom for bedrock. A piece of heavy canvas or a tarp is then spread at the bottom of the face to be sampled and this is positioned to catch all material falling from the sample cut. Starting at the bottom, a uniform rectangular channel is cut upward to the top of the prospect pit or in some cases, to the top of a particular formation or sample increment. When starting a sample, the cuttings are usually allowed to fall on the canvas but when sufficient room becomes available, it is best to catch them in a suitable box or metal container held close to the point of cutting. As the sample channel advances upward, the cuttings are periodically transferred to one or more sample sacks which should be kept in the sampler's possession or under surveillance throughout the sampling operation. In most situations an ordinary prospect pick will be found satisfactory for cutting channel-type placer samples.

How large should the channel cut be? There is no simple answer because like other aspects of placer sampling there may be special factors to consider in each case. Speaking generally, however, it will be found that experienced placer samplers usually select a size somewhere between 3" x 6" and 12" x 12" in cross section but, contrary to popular belief, there is no minimum or optimum size which by itself will insure an adequate sample.

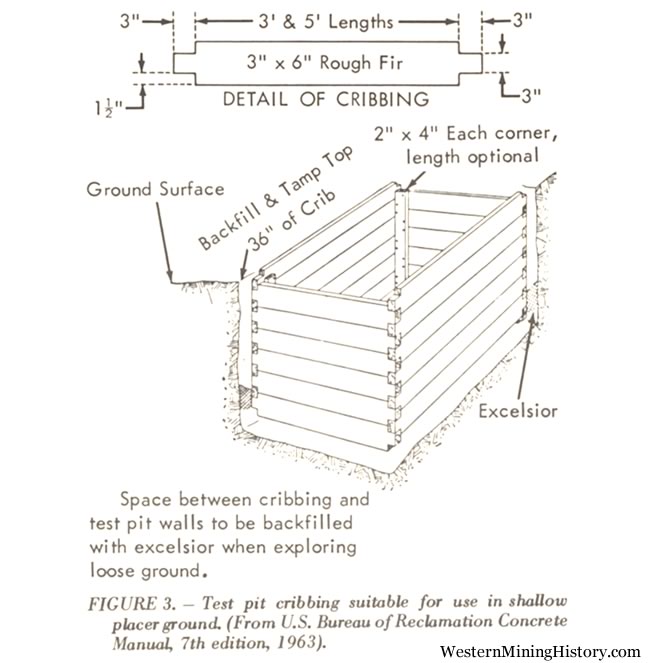

In ground where the water level is several feet below the surface, it is sometimes possible to sink pits or small shafts to bedrock using only buckets or a small pump to remove the water. These wet excavations are usually difficult to keep squared up but. in any case, some form of ground support may be needed to eliminate the working hazard and to minimize sampling errors which result when inflowing water carries values into the pit. A simple, easily-framed style of cribbing suitable for most shallow work is shown in Figure 3.

In loose, water-logged ground it may be impracticable to sink prospect shafts without the use of telescoping steel caissons. Certain problems and special procedures associated with caisson work have been discussed by Steel (1915, pp. 66-68) and Dohney (1942, pp. 48-49),

At first glance the use of hand-dug pits or shafts would seem to be an effective inexpensive way of prospecting shallow placers but this approach is too expensive for general use today, where a high dollar value must be placed on time. Nevertheless, hand-dug excavations intelligently used can serve a useful purpose in that, under favorable conditions, a few well located pits or shafts may indicate the value of a prospect before any great expenditure of money is made.