The Central Eureka Mine is a gold mine located in Amador county, California at an elevation of 1,611 feet.

About the MRDS Data:

All mine locations were obtained from the USGS Mineral Resources Data System. The locations and other information in this database have not been verified for accuracy. It should be assumed that all mines are on private property.

Mine Info

Elevation: 1,611 Feet (491 Meters)

Commodity: Gold

Lat, Long: 38.38294, -120.79690

Map: View on Google Maps

Central Eureka Mine MRDS details

Site Name

Primary: Central Eureka Mine

Secondary: Summit Mine

Commodity

Primary: Gold

Secondary: Silver

Location

State: California

County: Amador

District: Sutter Creek

Land Status

Land ownership: Private

Note: the land ownership field only identifies whether the area the mine is in is generally on public lands like Forest Service or BLM land, or if it is in an area that is generally private property. It does not definitively identify property status, nor does it indicate claim status or whether an area is open to prospecting. Always respect private property.

Administrative Organization: Amador County Planning Dept.

Holdings

Not available

Workings

Not available

Ownership

Not available

Production

Not available

Deposit

Record Type: Site

Operation Category: Past Producer

Deposit Type: Hydrothermal vein

Operation Type: Underground

Discovery Year: 1855

Years of Production:

Organization:

Significant: Y

Deposit Size: M

Physiography

Not available

Mineral Deposit Model

Model Name: Low-sulfide Au-quartz vein

Orebody

Form: Tabular, pinch and swell

Structure

Type: R

Description: Bear Mountains Fault zone, Melones Fault zone

Type: L

Description: Melones Fault zone

Alterations

Alteration Type: L

Alteration Text: Wall rocks hydrothermally altered, having been partially to completely converted to ankerite, sericite, quartz, pyrite, arsenopyrite, chlorite, and albite. Locally, greenstone bodies adjacent to the quartz veins contain enough disseminated auriferous pyrite in large enough bodies to constitute low-grade ore.

Rocks

Name: Greenstone

Role: Host

Age Type: Host Rock

Age Young: Late Jurassic

Name: Slate

Role: Host

Description: black

Age Type: Host Rock

Age Young: Late Jurassic

Analytical Data

Not available

Materials

Ore: Gold

Ore: Pyrite

Ore: Arsenopyrite

Gangue: Slate

Comments

Comment (Workings): The Central Eureka Mine was accessed through the main Central Eureka shaft, a 3-compartment shaft (2 skipways and 1 manway). This shaft struck the hanging wall, or contact, vein at 500 feet and followed it to about 2000 feet where the shaft passed into footwall slate and then continued to a total depth of 4855 feet. After acquisition of the Old Eureka Mine in 1924, the mine also utilized the Old Eureka shaft which was 3500 feet deep with an 11 x 5 foot inclined winze sunk from the 3500 to 4150 feet for working the lower levels at 3700', 3800', 3900', and 4150 feet. Ore was hoisted up the Central Eureka shaft while the haulage of men, supplies, timber, and waste was confined to the Old Eureka shaft (Carlson and Clark, 1954). The Central Eureka shaft was 1800 feet south of the Old Eureka shaft. Each had an average incline of 65?-75? east. Additionally, the 2700-foot inclined South Eureka shaft, on an adjoining property, was maintained for ventilation and pumping. Levels In the Central Eureka shaft were turned at intervals of about 100 to 200 feet depending on conditions. The deepest level was 4855 feet. From 1919 to 1930, the mine was deepened from 3500 feet to the bottom with levels at 2900, 3100, 3400 3500'. 3600', 3760', 3900', 4100', 4250',4400', 4550', 4700', and 4855 feet (Logan 1934). During this time, the South Eureka Mine was under option and was prospected on the 3350', 3900', and 4100' levels. The 3900 foot level was run south 1180 feet from the shaft, extending some distance into the South Eureka, and a crosscut was run 740 feet east in the slate from this level through several vein formations and gouge seams, without finding ore (Logan, 1934). The 4100 foot level was also extended into South Eureka ground (Logan, 1934). Between 1935 and 1938, the Central Eureka Mining Company also ran exploration drifts north from the 2100 and 2500-foot levels of the Old Eureka Workings into the adjoining Lincoln Consolidated Mine property. A total of 2467 feet of drifting and crosscutting was completed on both levels without finding any commercial ore (Carlson and Clark, 1954). Illustrations of some of the Central Eureka Mine workings are given by Spiers (1931) and Zimmerman (1983). Due to the heavy ground conditions, the cut and fill method of stoping was used. Ore was extracted by square set stoping for support in conjunction with waste filling. Ore was removed in horizontal cuts across stope faces up to 30 feet wide and 100 feet long. Timbers were placed in position as soon as room was available and no opening over 2 sets (16 feet) in height was made without filling with waste (Spiers, 1931). Originally waste rock was used for backfilling, but in 1946 sand from spent tailings was used to fill the stoped out areas. Ore from the lower stopes was loaded into mine cars, trammed to the transfer chutes, and hoisted up the 3500 winze to the main haulage way on the 3500-foot level. Electric locomotives transported ore cars 3000 feet south to the Central Eureka shaft where a double drum steam hoist brought the ore to the surface in 3-ton skips.

Comment (Geology): Ore Genesis Several mechanisms have been suggested as the source of the Mother Lode gold deposits. The most widespread belief is that plutonic activity magmatically differentiated vein constituents or provided the heat to circulate meteoric fluids or to metamorphose the country rocks to liberate the vein constituents. Knopf (1929) proposed that carbon dioxide, sulfur, arsenic, gold, and other constituents were emitted from a crystallizing magma but the components were carried by meteoric water in a circulation system driven by plutonic heat. Most theories suggest that gold deposits formed at temperatures of 300 to 350 degrees centigrade with a possible magmatic or metamorphic origin. Zimmerman (1983) proposed that the Mother Lode veins were generated by and localized near a major late Nevadan shear zone, the mechanism of ore genesis being the shearing and redistribution of mass within a major fault zone. He suggested that the early reverse faults had strike slip component, which is evident in the correlation of expected strike-slip dilatant zones with the geometries and steeply raking attitudes of the ore shoots. Fault movement and shearing would cause recrystallization of the rocks within the fault zone, releasing the more mobile elements including gold and most of the other vein constituents. Moreover, the heat generated by shearing would contribute to the metamorphism of the rocks in the fault zone and cause fluid circulation in the fault zone. Mineral laden auriferous fluids generated by this shearing channeled into the fault fracture system into dilatant zones, which represented avenues of increased flow and lower strain. LOCAL GEOLOGY The Mother Lode belt at the Central Eureka Mine is about 1600 feet wide and composed mostly of Mariposa Formation black slate. In the footwall, however, are several beds of andesite altered to greenstone. The rocks dip east at a slightly steeper angle than they do elsewhere on the Mother Lode. Mineralized zones in the Central Eureka and Old Eureka mines consisted chiefly of quartz veins, quartz-ankerite-albite rock, ribbon or banded structures of intercalated quartz and crushed slate paralleling the vein walls. Gold occurred as free-milling gold in quartz, or intergrown with disseminated sulfides. The principal sulfides were pyrite and arsenopyrite with sphalerite, chalcopyrite, and galena present in minor amounts. At least eight separate veins were encountered in the Central Eureka Mine (Zimmerman, 1983). However, only 2 veins accounted for the majority of the mine's production.

Comment (Commodity): Commodity Info: Quartz ores ranged from $3 -$4 a ton up to $70 a ton

Comment (Commodity): Ore Materials: Free-milling ribboned quartz and slate seams and mineralized greenstone ?gray ore?. Gray ore contained a few percent auriferous sulfides, principally pyrite and arsenopyrite.

Comment (Commodity): Gangue Materials: Slate, greenstone

Comment (Identification): The Central Eureka Mine is situated in the most productive part of the Sierra Nevada Mother Lode belt, the 10-mile portion that lies between the towns of Plymouth and Jackson in Amador County. The Central Eureka Mine was one of the three largest mines on the Mother Lode (Central Eureka, Argonaut, and Kennedy mines). While the mine is technically in the smaller Sutter Creek district, the uniform nature of gold mineralization with neighboring districts has caused some authors to consolidate the smaller neighboring districts into Jackson - Plymouth district (Clark, 1970), which, in sum, was the most productive district of the Mother Lode belt with an estimated total production of about $180 million (Clark, 1970). Prior to 1924, the Central Eureka Mine (formerly the Summit Mine) was operated independently, having produced about $8.3 million by that time. Following a decline in its ore values and increasing costs, the Central Eureka Mining Company purchased the adjoining Old Eureka Mine Company in 1924 and consolidated it with the Central Eureka Mine. Between 1924 and 1930, the Central Eureka Mining continued to mine both properties. From 1930 until its closure in the 1950s, all produced ore came from the former Old Eureka mine workings. In total, the consolidated Central Eureka Mine is credited with producing $36 million (Clark, 1970).

Comment (Location): Location selected for latitude and longitude is the Central Eureka Mine shaft symbol on the USGS 7.5 minute Amador City quadrangle.

Comment (Workings): In its final years of operation, ore was run through a jaw crusher, 30-stamp mill of 9 tons per hour capacity, jig classifier, conditioner, and flotation cells. The gold and concentrate from the jig was delivered to two Knudsen bowls, an amalgam barrel, retorted, and sent to the U.S. Mint in San Francisco. The gold and concentrate slimes, as well as the slimes from the flotation cells were tabled and sent to a Dorr thickener, after which the gold concentrates were delivered to a 12-foot hydro-separator. The products from the separator went to a cyanide plant or were reground in a pebble mill and sent to another Knudsen bowl. The fines from the bowl were sent to the amalgam barrel while the slimes were run over a corduroy table and recirculated through the hydro-separator. Mill recovery averaged 95% with approximately 70% of the gold recovered by amalgamation and 30% recovered through concentrates. The mill sand discharge was delivered to settling tanks where one pound of aluminum sulfate was added to each ton of discharge to aid in settling. Thirty percent of the discharge was discarded on the tailings pond, while the remaining 70% of the sand was mixed with water and pumped down the Old Eureka shaft for backfilling. This process could deliver up to 30 tons of sand per hour for use as backfill (Carlson and Clark, 1954).

Comment (Development): Most of the important lode gold deposits in Amador County Mother lode were discovered in the 1850s while rich Tertiary placer deposits were being worked. While many of the neighboring mines were very profitable by 1875, the Central Eureka Mine (and nearby Argonaut, Kennedy, Bunker Hill, Fremont-Gover, and Lincoln Consolidated mines) did not become a major producers until the 1880s and 1890s. The Central Eureka Mine was located in 1855 as the Summit Mine. Eleven years later, a shaft was sunk to a depth of 550 feet and about 1000 tons of ore worth $30,000 was produced from a depth of 165 feet. However, the bottom workings failed to find additional ore. A second shaft, the Central Eureka shaft, was sunk to a depth of 700 feet but also failed to find ore. By 1875 mining ceased and the mine machinery was dismantled and sold. In 1893, the Summit property was sold for $6,000 and incorporated under the name of the Central Eureka Mining Company. Since 1893, with the exception of several minor shutdowns, operations remained relatively continuous until its final closure in either 1951 or 1953. A 10-stamp mill was built in 1900, but production started before this, the ore being crushed at that nearby Zeila mill. The Central Eureka shaft was deepened from 700 to 2500 feet by 1907. The mine operated profitably until 1907, paying large dividends. The operations during this period were on the hanging wall vein between 1000 to 2500 feet inclined depth. The mine closed down for one year in 1907, but it was reopened in 1908. For the next ten years, the mine operated at a loss. Ore values declined to between $3 - $4 per ton, and numerous assessments were levied on the shareholders. By 1914, the shaft had reached 2825 feet. By 1916, only a few short, low-grade ore shoots had been found, the plant was getting old, and the shaft was falling into disrepair (Logan 1927). Also, due to the converging of the end lines in the direction of the dip, the length of holdings along the hanging wall vein was shortening on each successive level. The retiring directors concluded the mine was exhausted and recommended the mine be closed (Logan, 1934). However, the incoming board of directors decided to go forward. An evaluation of the property recommended that the east and west parts of the property be explored since the former work had been confined to the central part of the lode. By early 1919, the 3500-foot level had been reached and a crosscut on this level revealed a good ore shoot. In a winze below the 3500-foot level, a sublevel was turned and run both ways in good ore (Logan, 1934). By this time, while the stockholders were facing their 48th assessment, the mine entered a bonanza period. During the following 11 years, the mine was very productive with each year resulting in dividends to shareholders. In 1924, the adjoining Old Eureka Mine (comprising the Amador, Maxwell, Alpha, and Railroad claims and 136 acres of adjoining land) was purchased, a new steel head frame was built, and many other upgrades and improvements were made (Logan, 1934). The Old Eureka Mine was first opened in 1852. In 1886, after reaching a depth of about 2000 feet, and having produced about $16,000,000, it was idled for a period of 30 years. In 1916, the property was purchased for $500,000. The Old Eureka shaft was reopened and extended it to a depth of 3500 feet inclined distance (3212 feet vertically), and several new levels were driven without finding commercial ore in paying quantities. Work on the Old Eureka was again discontinued in 1921 (Spiers, 1931) until reactivated by the Central Eureka Mining Company.

Comment (Geology): REGIONAL GEOLOGY The Central Eurake Mine is located within the Sierra Nevada foothills, where bedrock consists of north trending tectonostratigraphic belts of metamorphosed sedimentary, volcanic, and intrusive rocks that range in age from late Paleozoic to Mesozoic. Locally, the Mesozoic rocks are capped by erosional remnants of Eocene auriferous gravels and once extensive volcanic rocks of Tertiary age. The structural belts, which extend about 235 miles along the western side of the Sierra, are flanked to the east by the Sierra Nevada Batholith and to the west by sedimentary rocks of the Cretaceous and Jurassic Great Valley sequence. In Amador County, the structural belts are internally bounded by the Melones and Bear Mountains fault zones. Schweickert and others (1999) provide one interpretive overview of the regional geology of this part of the Sierra Nevada. Gold deposits in the Plymouth - Jackson district occur within the north and northwest trending mile-wide Mother Lode Belt, which is dominated by gray to black slate of the Upper Jurassic Mariposa Formation and associated greenstone and amphibolite schist bodies assigned to its Brower Creek Volcanics member. In Amador County, the Mother Lode Belt approximately parallels Highway 49 southeastward from Plymouth through the town of Jackson. The geology of this segment has been mapped by Zimmerman (1983) and Duffield and Sharp (1975). The lode gold deposits along this stretch are responsible for most of the gold production in the county, which has been reported to be 7.68 million ounces (Koschman and Bergendahl, 1968). Clark (1970) placed the value of this production at $180 million. The Amador County portion of the belt was one of the most productive gold mining areas in the United States, and the Plymouth - Jackson district in Amador County was the most productive part of the belt. The Mariposa Formation contains a distal turbidite, hemipelagic sequence of black slate, amphibolite, schist, and fine-grained tuffaceous rocks, and volcanic intrusive rocks. The thickness of the Mariposa Formation is difficult to ascertain due to structural complexities, but is estimated to be about 2,600 feet thick at the Cosumnes River. Massive greenstone of the Upper Jurassic Logtown Ridge Formation lies west of the Mother Lode Belt. The contact between the Logtown Ridge and Mariposa Formation is generally gradational (Zimmerman, 1983). The Logtown Ridge Formation consists of over 9,000 feet of volcanic and volcanic-sedimentary rocks of island arc affinity. These rocks are mostly basaltic and include flows, breccias, and a variety of layered pyroclastic rocks. Metasedimentary rocks, chiefly graphitic schist, metachert, and amphibolite schist of the Calaveras Complex (Carboniferous to Triassic) are to the east. Mother Lode Gold Quartz Veins Mother Lode-type veins fill voids created within faults and fracture zones. The Mother Lode Belt consists of a vein system ranging from a few hundred feet to a mile or more in width. The vein system consists of a fault zone containing several parallel veins separated by hundreds of feet of highly altered country rock containing small quartz veins and occasional bodies of low-grade ore. Veins are generally enclosed within numerous discontinuous fault fissures within Mariposa Formation slate, associated greenstone, amphibolite schist, or along lithologic contacts. Mineralized fault gouge is abundant.

Comment (Development): Below the 4500-foot level, the ground turned out to be so badly broken that shaft and drift maintenance and other underground repairs were costing more than breaking the ore. Nonetheless, the veins continued to be developed deeper and deeper until the Central Eureka bottomed at 4855 feet. Together with a declining gold content in the ore, these conditions led to a substantial operating loss in 1930. The lower workings of the Central Eureka were abandoned and all pipes, rails, pumps, and other equipment from the deeper levels and the tracks in the shaft below 3900 feet were taken up. Having produced $8,321,925 in gold and paid out $1,263,973 in dividends, this ended all mining operations on the original Central Eureka Mine claims. After 1930, all ore produced by the Central Eureka Mining Company came from the Old Eureka Mine workings (Carlson and Clark, 1954). Development of the Old Eureka workings proved to be quite profitable, and by 1939, the Central Eureka Mine was the best paying mine on the Mother Lode. In 1930, a partnership took an option on the Central Eureka mine tailings between 1932 and 1938, and a total of 880,000 tons of tailings were treated. Assays varied from $1.50 - $3.00 per ton, with recovery of about 70%. The tailings were hydraulically sluiced to a classifier. Both sands and slimes were then treated with 3 pounds of coal tar per ton to prevent precipitation from the carbonaceous content. The sands were treated in leaching vats. The slimes were directed to an agitator, thickener, and filters. Sand and slime residues were discarded. Cyanide precipitates were acid treated, roasted, and melted in to gold bars. As were all gold mines in the district, the Central Eureka Mine was shut down in 1942, but in anticipation of its reopening, it was kept in working order during WWII. Mining was resumed in 1946 but little ore was produced until 1948. In 1951, 39,440 tons of ore yielded a little more than $500,000, but because of greatly increased costs, the Central Eureka was permanently shut down in the early 1950s. Various reports place its final year of operation as 1951 or 1953. It was the last active major gold mine on the Mother Lode with a total production of approximately $36 million (Carlson and Clark, 1954).

Comment (Deposit): The Central Eureka Mine produced from typical Mother Lode-type low-sulfide mesothermal gold-quartz veins. The producing veins are part of a single NNW-SSE striking, steeply dipping vein system that extends southward through the town of Sutter Creek to the Central Eureka mine, and from which the nearby prolific Kennedy, Argonaut, and Lincoln Consolidated mines produced. While several veins were encountered in the mine, the principal veins included the main hanging wall or contact vein which occupied the main fault zone, and footwall veins embedded in Mariposa Formation slate. The thickness of the ore mined usually ranged between 1 and 12 feet with ore shoots assaying from less than $3 per ton to $70 per ton. Mineralization consisted chiefly of ribbon or banded structures of intercalated quartz and crushed slate paralleling the vein walls. Gold occurred as free-milling gold in quartz, or intergrown with disseminated sulfides. The principal sulfides were pyrite and arsenopyrite with sphalerite, chalcopyrite, and galena present in minor amounts. Lower-grade altered greenstone wall-rock ore ("gray ore) was also present.

Comment (Geology): Hanging wall or Contact vein The principal vein worked in the early workings was the so-called hanging wall, or contact, vein, which occupied the main fault plane fracture zone. The vein is not straight in strike but rolls in a series of long swells, and gouge is always found on the footwall side. Long, lenticular masses of quartz within the vein form the ore shoots. Some ore shoots in this vein reportedly averaged about $70 per ton. In the upper workings, this vein consisted of a simple single fissure cutting in strike and dip the black slates and greenstone wall rocks (Storms, 1900). Above the 1000-foot level, this vein was enclosed in slate walls. Below 1000 feet, the hanging wall slate turned to greenstone. The ore shoot on this vein extended from near the 1000-foot level to the 2540-foot level and ranged from 1-12 feet thick, with its greatest stope length about the 1500-foot level. Several short, narrow ore shoots were found at a depth of about 1000 feet, and these increased in length and width until they merged to form one large ore shoot at 1850 feet (Logan, 1934). The exact tonnage from this shoot is unknown but was probably about 300,000 tons, which was worked between 1896 and 1907, averaging about $7.16 per ton (Logan, 1934). At a depth of 3300 feet, ore shoots within this vein became too low grade to mine profitably and mining of the Contact vein ceased at a depth of 3350 feet. The average yield between 1908-1919 was only $3-$4 a ton, and the size of the ore bodies, even at this grade, kept decreasing. Between the 2540 and 3425-foot levels, most of the rock milled did not pay expenses and what ore was encountered soon gave out (Logan, 1934). Low-grade mineralization of the greenstone wall rock was common upon nearing veins and ore shoots. Mineralization was generally in the form of disseminated sulfides, chiefly pyrite and arsenopyrite. In some cases mineralization was sufficient to form low-grade but profitable ore bodies. Footwall vein On the 3500-foot level, a new ore-bearing vein was discovered in the foot wall. From 30 to 70 feet of intervening Mariposa slate separate the two veins (Spiers, 1931). The footwall vein ore shoot on the 3760-3900 foot levels was 340 feet long and averaged 9-10 feet wide, filled with quartz ribbon rock and gouge. On the 3500-foot level, ore was in two shoots, a north and a south shoot, separated by 160 feet of low-grade filling. During the year ending April 22, 1920, a total of 34,705 tons of ore were milled from the 3500', 3600', and 3700' levels with an average assay value $13.15 with a recovery rate of 94.31% (Logan, 1921). About one quarter of the ore came from the 3500-foot level south shoot, but this shoot was spotty and apparently faulted between the 3500 and 3700 foot levels. Ore from the north shoot averaged over $20 per ton (Logan, 1921). The most important and productive level of the mine was the 4550-foot inclined level in the footwall vein. At this level a spur vein striking N 25? W joins the footwall vein. This spur vein provided good ore and was stoped for 165 feet from its junction with the main vein, which it joined about the center of the main footwall ore shoot which measured 425 feet long. Ores from these levels assayed $10 -$14 per ton.

Comment (Geology): Mineralization is characterized by steeply dipping massive gold-bearing tabular quartz veins striking north to northwest and dipping between 50 to 80? east. Veins are discontinuous along both strike and dip, with maximum observed unbroken dimensions of 6,500 feet in either direction (Zimmerman, 1983), but individual veins more commonly range from structures 3,000 feet long and 10 to 50 feet wide to tiny veinlets. In rare instances, veins are known to reach as much as 200 feet thick (Keystone Vein). Veins may be parallel, linked, convergent, or en echelon, and commonly pinch and swell. Few can be traced more than a few thousand feet. At their terminations, veins pass into stringer zones composed of numerous thin quartz veinlets or into gouge filled fissures (Knopf, 1929). Ores consist of hydrothermally deposited minerals and altered wall-rock inclusions. Gold occurs as free gold in quartz and as auriferous pyrite and arsenopyrite. Quartz is the dominant mineral component in the veins, comprising 80-90% or more with ankerite, arsenopyrite, pyrite, albite, calcite, dolomite, sericite, apatite, chlorite, sphalerite, galena, and chalcopyrite in lesser amounts of a few percent or less. Cumulative sulfides generally range 1% - 3% of the rock (Carlson and Clark, 1954; Zimmerman, 1983). Ore grade material is not evenly distributed throughout the veins, but was localized in ore shoots, which tend to occur at vein intersections, at intersections of veins and shear zones, or at points where the veins abruptly change strike or dip (Moore, 1968). Ore shoots generally display pipe-like geometries raking steeply in the veins at 60-90%. Horizontal dimensions of the ore shoots are commonly 200-500 feet, but pitch lengths were often much greater, and often nearly vertical. Pockets of high grade ore are relatively abundant. Single masses of gold containing over 2,000 ounces and single pockets containing more than 20,000 ounces have been found. Silver is subordinate. Gold fineness averages 800. While most of the Mother Lode ore shoots mined have been less than 300 feet in strike length, many have extended down dip for many thousands of feet. In the deeper mines, mining continued to almost 6,000 feet on the dip of the vein with no evidence of bottoming. Cessation of operations in the deep Kennedy (5912') and Argonaut (5570') mines was caused by increasing costs at the greater depths rather than an absence of ore. Milling ore was generally low to moderate in grade (1/7 to 1/3 ounce per ton). Alteration Wall rocks have invariably been hydrothermally altered, having been partially to completely converted to ankerite, sericite, quartz, pyrite, arsenopyrite, chlorite, and albite with traces of rutile and leucoxene (Knopf, 1929). The mineralization is usually adjacent to the veins in ground that has been fractured and contains small stringers and lenses of quartz.. Locally, greenstone bodies (altered volcanic rocks) adjacent to the quartz veins contain enough disseminated auriferous pyrite in large enough bodies to constitute what has been called "gray ore". Altered slate wallrock commonly contains pyrite, arsenopyrite, quartz, chlorite, and sericite with or without ankerite (Zimmerman, 1983). Large bodies of mineralized schist also form low-grade ore bodies throughout the Mother Lode. This ore consists of amphibolite schist which has been subjected to the same processes of alteration, replacement, and deposition that formed the greenstone gray ores. The altered schist consists mainly of ankerite, sericite, chlorite, quartz, and albite. Gold is associated with the pyrite and other sulfides that are present. Pyrite comprises about 8 percent of the rock. The average grade of mineralized schist is about 0.1 oz per ton (Moore, 1968).

Comment (Economic Factors): Clark (1970) credited the Consolidated Central Eureka Mine (Central Eureka and Old Eureka mines) with a total production of $36 million. Logan (1934) attributed $8.3 million of this amount to the original Central Eureka Mine before its consolidation with the Old Eureka mine and the cessation of work in the Central Eureka workings. The grade of ore in the Central Eureka Mine ranged from less than $4 to over $20, but in general the Mother Lode mines are characterized by low-grade ores.

References

Reference (Deposit): Carlson, D.W., and Clark, W.H., 1954, Mines and mineral resources of Amador County, California: California Division of Mines and Geology, 50th Report of the State Mineralogist, p. 173-177.

Reference (Deposit): Schweickert, R.A., Hanson, R.E., and Girty, G.H., 1999, Accretionary tectonics of the Western Sierra Nevada Metamorphic Belt in Wagner, D.L. and Graham, S.A., editors, Geologic field trips in northern California: California Division of Mines and Geology Special Publication 119, p. 33-79.

Reference (Deposit): Spiers, J., 1931, Mining methods and costs at the Central Eureka Mine, Amador County, California: Bureau of Mines Information Circular 6512, 13 pp.

Reference (Deposit): Storms, W.H., 1900, The Mother Lode region of California: California Mining Bureau Bulletin 18, p 64-65.

Reference (Deposit): Tucker, W.B., 1914, Amador County, Central Eureka (Summit) Mine: California State Mining Bureau, 14th Annual Report of the State Mineralogist, p. 24.

Reference (Deposit): Zimmerman, J.E., 1983, The Geology and structural evolution of a portion of the Mother Lode Belt, Amador County, California: unpublished M.S. thesis, University of Arizona, 138 p.

Reference (Deposit): Additional information on the Central Eureka Mine is available in file no. 322-5941 (CGS Mineral Reources Files, Sacrament)o.

Reference (Deposit): Clark, W. B., 1970, Gold districts of California: California Divisions of Mines and Geology Bulletin 193, p. 69-77.

Reference (Deposit): Duffield, W.A. and Sharp, R.V., 1975, Geology of the Sierra foothills melange and adjacent areas, Amador County, California: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 827, 30 p.

Reference (Deposit): Logan, C.A., 1921, Amador County, Central Eureka Mine: California State Mining Bureau, 17th Report of the State Mineralogist, p. 409-410.

Reference (Deposit): Logan, C.A., 1927, Amador County, Central Eureka Mine: California State Mining Bureau, 23rd Report of the State Mineralogist, p. 158-165.

Reference (Deposit): Logan, C.A., 1934, Mother Lode gold belt of California: California Division of Mines Bulletin 108, p. 74-80.

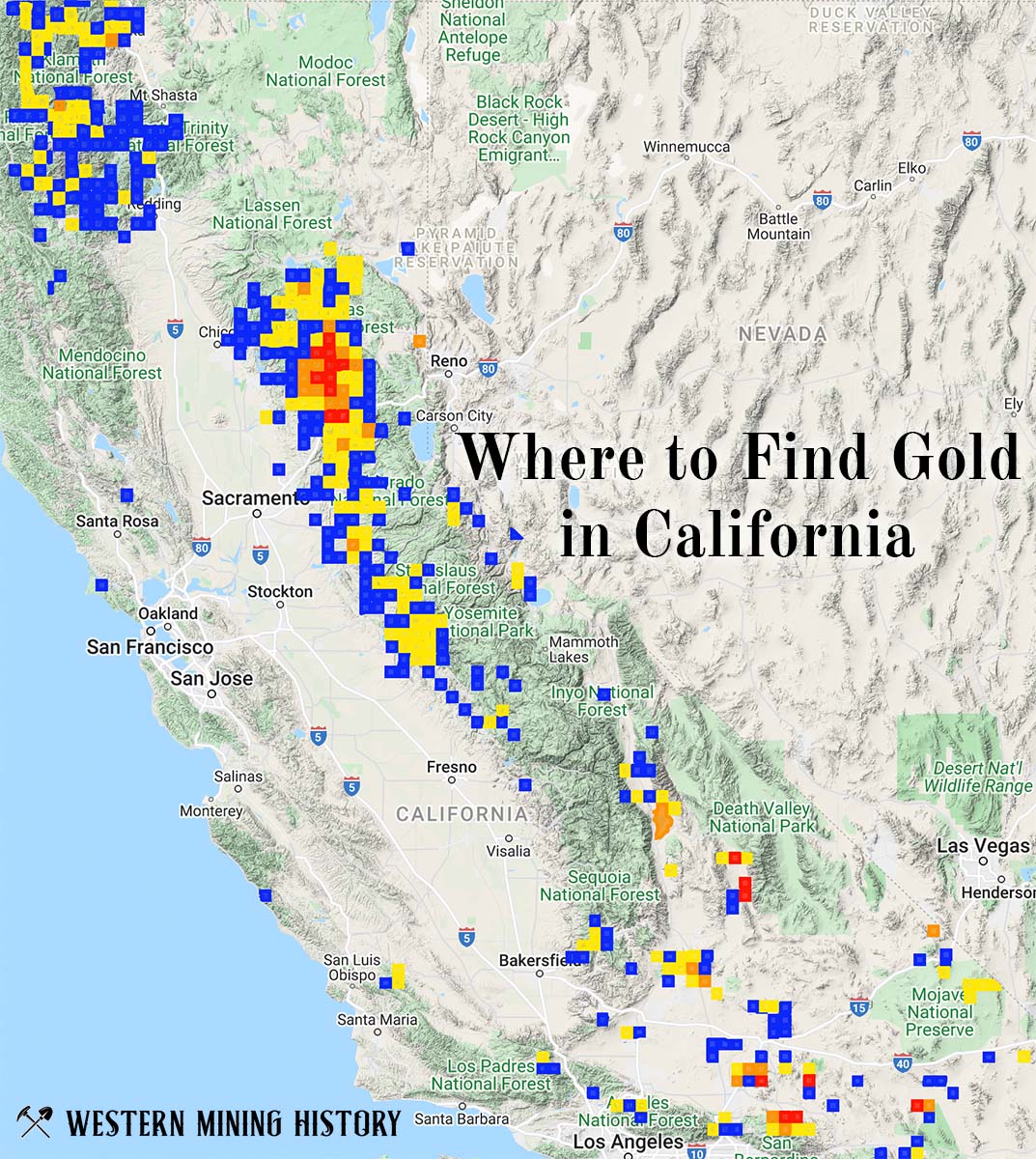

California Gold

"Where to Find Gold in California" looks at the density of modern placer mining claims along with historical gold mining locations and mining district descriptions to determine areas of high gold discovery potential in California. Read more: Where to Find Gold in California.