The Volcano District is a gold mine located in Amador county, California at an elevation of 2,057 feet.

About the MRDS Data:

All mine locations were obtained from the USGS Mineral Resources Data System. The locations and other information in this database have not been verified for accuracy. It should be assumed that all mines are on private property.

Mine Info

Elevation: 2,057 Feet (627 Meters)

Commodity: Gold

Lat, Long: 38.44261, -120.63028

Map: View on Google Maps

Volcano District MRDS details

Site Name

Primary: Volcano District

Commodity

Primary: Gold

Location

State: California

County: Amador

District: Volcano

Land Status

Land ownership: Private

Note: the land ownership field only identifies whether the area the mine is in is generally on public lands like Forest Service or BLM land, or if it is in an area that is generally private property. It does not definitively identify property status, nor does it indicate claim status or whether an area is open to prospecting. Always respect private property.

Administrative Organization: Amador County Planning dept.

Holdings

Not available

Workings

Not available

Ownership

Not available

Production

Not available

Deposit

Record Type: District

Operation Category: Past Producer

Deposit Type: Stream Placer

Operation Type: Surface

Discovery Year: 1848

Years of Production:

Organization:

Significant: Y

Physiography

Not available

Mineral Deposit Model

Model Name: Placer Au-PGE

Orebody

Form: Irregular, lens

Structure

Type: R

Description: Calaveras-Shoofly thrust fault, Melones Fault zone

Alterations

Alteration Type: L

Alteration Text: NA

Rocks

Name: Sand and Gravel

Role: Host

Age Type: Host Rock

Age Young: Tertiary

Analytical Data

Not available

Materials

Ore: Gold

Gangue: Quartz

Comments

Comment (Identification): The Volcano district is centered around the old community of Volcano in western Amador County, California. It was the center of early hydraulic mining in Amador County. The placers consisted of Tertiary gravels deposited largely by the ancestral Mokelumne River. Some placer deposits in the north part of the district are though to been deposited by the ancestral Consumnes River (Clark, 1970). The district includes mostly hydraulic and drift mines but a few narrow gold quartz veins were also mined in the district (Clark, 1970). Very little information is available about the specific Volcano district mining operations or production statistics. Koschmann and Bergendahl (1968) estimated that the district produced no more than 100,000 ounces of gold before 1932.

Comment (Location): Location selected for latitude and longitude is the intersection of Volcano Road and Rams Horn Grade Road in the town of Volcano on the USGS 7.5 minute West Point quadrangle.

Comment (Workings): There are no available records regarding specific mining operations in the Volcano district, with little more than references to extensive hydraulic mining operations. Hydraulic mining allowed the bulk processing of large volumes of low yield gravels that would otherwise prove unprofitable by other methods of mining. Hydraulic mining involved directing a powerful stream of high pressure water through large monitors (nozzles) at the base of a gravel bank, undercutting it and allowing it to collapse. Large gravel banks several hundred feet high were mined in this manner, but larger banks were often mined in two or more benches. Often, adits were driven into the exposed face and crosscuts parallel to the face were loaded with dynamite to help break down the exposure. The loosened gravels were then washed through long sluice boxes lined with riffles or over devices to mechanically trap the gold. Mercury was added to amalgamate the finer gold. The remaining debris was indiscriminately dumped in the nearest available stream or river. One of hydraulic mining's highest costs was in the ditches, flumes and reservoirs needed to supply sufficient volumes of water at high pressure. A mine usually needed its own system of ditches and flumes to deliver water from distant and higher reservoirs or rivers as well as dams, pipes and tunnels. Another costly undertaking was finding an outlet for the debris. As the gravels were washed lower and lower in the ancient channel beds, it was often necessary to drive a tunnel through the bedrock channel rim to drain the workings into a nearby valley. Hydraulic mining flourished for about 30 years until the mid 1880s when the Sawyer Decision curtailed debris disposal.

Comment (Geology): REGIONAL GEOLOGY The Volcano District is within the Sierra Nevada foothills, where bedrock consists of north trending tectonostratigraphic belts of metamorphosed sedimentary, volcanic, and intrusive rocks that range in age from late Paleozoic to Mesozoic. Locally, the Mesozoic rocks are capped by erosional remnants of Eocene auriferous gravels and once extensive volcanic rocks of Tertiary age. The structural belts, which extend about 235 miles along the western side of the Sierra, are flanked to the east by the Sierra Nevada Batholith and to the west by sedimentary rocks of the Cretaceous and Jurassic Great Valley sequence. The structural belts are internally bounded by the Melones and Bear Mountains fault zones. All the belts are characterized by extensive faulting, shearing, and folding. In the Amador County area, lode gold deposits within the Mother Lode Belt are responsible for most of the gold produced in the county. Significant, but largely unknown, amounts of placer gold were also produced from rich Tertiary gravel deposits, the Volcano district deposits being among the most productive in the county. The Mother Lode Belt consists of the upper Jurassic Logtown Ridge and upper Jurassic Mariposa formations. The Logtown Ridge Formation consists of over 9,000 feet of volcanic and volcanic-sedimentary rocks of island arc affinity. These rocks are mostly basaltic and include flows, breccias, and a variety of layered pyroclastic rocks. The overlying Mariposa Formation contains a distal turbidite, hemipelagic sequence of black slate, amphibolite, schist, and fine-grained tuffaceous rocks, and subvolcanic intrusive rocks. The thickness of the Mariposa Formation is difficult to ascertain due to structural complexities, but is estimated to be about 2,600 feet thick at the Consumnes River. The contact between the Logtown Ridge and Mariposa Formation is generally gradational (Zimmerman, 1983). Mother Lode Belt mineralization is generally characterized by steeply dipping gold-bearing quartz veins that traverse western El Dorado and Amador counties. In Amador County, the belt approximately parallels Highway 49 southeastward from Plymouth through the town of Jackson. The belt trends north through Nashville, northeast through Placerville, and northwest to Garden Valley. The Mother Lode veins are generally enclosed in Mariposa Formation slate with associated greenstone. The vein system ranges from a few hundred feet to a mile or more in width. Within the zone are numerous discontinuous or linked veins, which may be parallel, convergent, or en echelon. The veins commonly pinch and swell. Few can be traced more than a few thousand feet. Mother Lode type veins fill voids created within faults and fracture zones and consist of quartz, gold and associated sulfides, ankerite, calcite, chlorite, and sericite (Clark and Carlson, 1956). The Melones Fault zone separates the Mother Lode Belt from the East Gold Belt. The East Belt is dominantly argillite, phyllite and phyllonite, and chert of Paleozoic age that have been assigned to the Carboniferous Calaveras Complex by most investigators. Lode deposits of the East Belt consist of many individual gold quartz veins within rocks of the Calaveras Complex, Shoo Fly complex, or in granitic rocks. Most of the veins trend northward and dip steeply. East Belt veins are smaller and narrower than those of the Mother Lode, but commonly are more chemically complex, and richer in grade.

Comment (Development): Who the first men were to mine in the Volcano district is not known for certain, but legend has it that among the earliest were members of Colonel Stevenson's 1st New York Volunteer regiment who chanced upon the placer gold deposits in 1848. They found the placers exceedingly rich, averaging $100 a day per man, with some spots yielding up to $500. The claims in Soldiers Gulch were paying so well that no one took the time off from mining to build any kind of permanent shelter. So when the first snows began to fly, most of the men packed up their gear and headed for friendlier climes. A few soldiers decided to dig in for the winter and continue working the placers, but the winter proved cruel, and without substantial shelter from the storm or adequate supplies, the soldiers perished. The following spring, word of the rich diggings at Soldier Flat was out and miners swarmed into the district. Some of the newcomers thought the bowl shaped valley the mining camp occupied was formed by volcano and the name stuck. The surface gravels paid handsomely and the claims seemed to get richer with depth. The digging was easy and men picked out large nuggets with only their fingers as tools. One miner is reported to have taken out $8,000 in only a few days, another took out twenty-eight pounds from a single pocket. Eventually the miners encountered a layer of yellow clay from which the gold was nearly impossible to extract. Discouraged, several claims were abandoned which later turned out to be worth fortunes when methods of separating the gold from the clay were discovered. Boiling was found to disintegrate the clay, so boilers were built to steam out the gold. Another method was to let the clay dry in the sun, after which it was pounded into dust to remove the gold. As early as 1849, Volcano was an election precinct, and within two years a post office had been established. The town really came into its own in 1852, when the Volcano cutoff off the Carson Route was completed. Before the year was out, as many as 300 clapboard and pine houses were scattered about the hillsides, and the population was nearing two thousand. The following year the town had 11 stores, 1 restaurant, 3 bakeries, 6 hotels, 3 boarding houses, and 3 bars and gambling houses. By 1855, the easily mined placers of Soldiers Gulch began to give out and hydraulic mining came into into favor. Ironically, the massive quantities of sediment liberated by hydraulic mining almost wiped out the town. Many of the buildings were undermined and dirt, sludge, and debris washed into homes and businesses. By 1865, most of the gold was gone, and so were most of the people. Volcano had suffered its share of fires over the years, and in 1868 the problem seemed epidemic. Property values had been dropping steadily since the end of the Civil War, but many of the businesses were heavily insured from earlier, more prosperous times. Numerous fires broke out that year, prompting a rumor that the property owners may have had something to do with them. The buildings which burned were not rebuilt, the owners simply left and the town slowly faded into the small community that it is today.

Comment (Economic Factors): Little information has been published on the Volcano district, and production data is not available. Koschmann and Bergendahl (1968) estimated that, of the 289,835 ounces of gold produced from placer in Amador County since 1903, the Volcano District probably produced not more than 100,000 ounces. Some estimates for the Volcano district place total production in the neighborhood of $90 million.

Comment (Geology): Gold particles tend to be flat or rounded and range from fine flour gold to nuggets of 100 or more ounces. The gold particles are everywhere associated with black sands composed of magnetite, ilmenite, chromite, zircon, garnet, pyrite, and in some places platinum. Detailed descriptions of the Tertiary channel deposits as well as a discussion of their geology are contained in U.S. geological Survey Professional Paper 73 (Lindgren, 1973). Information can also be found in Auriferous Gravels of the Sierra Nevada (Whitney, 1880), California Mining Bureau Bulletin 92 (Haley, 1923), California's Gold-bearing Tertiary channels (Jenkins and Wright, 1934), and California Division of Mines Bulletin 135 (Averill, 1946). Two distinct types of Tertiary auriferous river gravels can be recognized in the Sierra Nevada. Eocene auriferous gravels are characterized by abundant white quartz and a paucity of volcanic debris (excepting old metavolcanics). These are almost valways encountered in remnants of channels worn directly into crystalline bedrock or on terraces adjacent to the channels. They are commonly overlain by white rhyolite ash. In contrast, Miocene age interrhyolitic channel gravels contain abundant light colored rhyolitic debris as well as white quartz, but no dark colored andesitic debris. These are commonly found in channels cut into Eocene gravels or even in channels cut into rhyolite ash. These gravesl tend to be much less rich than the Eocene gravels although they occasionally robbed rich Eocene channels and themselves became locally productive (Carlson and Clark, 1954). Associated with the gold in the gravel deposits are heavy mineral grains commonly called "blank sands", and consisting predominantly of magnetite with varying amounts of ilmenite, rutile, platinum group metals, zircon, chromite, and garnet. LOCAL GEOLOGY The Tertiary Mokelumne River and its tributaries are responsible for the placer gold deposits in the Volcano and nearby districts. Locations of the relict Mokelumne River channel deposits are shown in the U.S. Geological Survey Jackson folio (Turner, 1894). The main channel flowed southwestward from Fort Grizzly in El Dorado County to the head of Sutter and Ashland creeks in Amador County. For the next 4 miles, the deposits were removed by erosion before recurring at Volcano and extending westward another 4 miles under a preserving cover of rhyolitic tuff to the head of Rancheria Creek. The auriferous placer gravels in the Volcano district were considerably less rich than those of the more northern Sierra Nevada Tertiary placers. Lindgren (1911) attributed this partly to the distribution of the old drainage channels, but also to a shorter period of accumulation. He noted that the bulk of the gravels are interrhyolitic, while the richer placers to the north tended to be prevolcanic (prerhyolitic) gravels resting on eroded basement rock. In southern Amador County, most of the basal gravels were swept away by the ancient river and much of the accumulation of auriferous gravels occurred during the rhyolitic period. The broad valleys became filled with gravels containing rhyolitic pebbles and by interbedded masses of rhyolite tuff. With the thickness of this detrital series reaching as much as 400 feet in exposures at Mountain ranch in neighboring Calaveras County (Lindgren, 1911). The gavels are generally capped by more compact flows of rhyolite and rhyolite tuffs. At about this time, the tilting of the Sierra and extensive andesitic eruptions began, interspersed with erosional periods during which the rhyolitic gravels were trenched in places and temporary interandesitic channels were established. Then followed the great flows of andesitic tuff, which covered a large portion of Amador County and obliterated the Tertiary channels.

Comment (Geology): Regionally, the northern Sierra Nevada experienced a long period of Cretaceous to early Tertiary erosion, after which it underwent extensive Oligocene to Pliocene volcanism. The oldest of the Tertiary units are basal Eocene auriferous gravels, which were preserved in paleochannels eroded into basement and adjacent bench gravels deposited by the predecessors of the modern Yuba, American, Consumnes, and Mokelumne rivers. In contrast to the earlier volcanism, Tertiary volcanism was continental and deposited on top of the eroded basement rocks, channel deposits, and Mesozoic intrusives. An important widespread unit of intercalated rhyolite tuffs and intervolcanic channel gravels is the Oligocene-Miocene Valley Springs Formation. The youngest volcanic unit, the Miocene-Pliocene Mehrten Formation, consists largely of andesitic flows overlying the Valley Springs Formation. Pliocene-Pleistocene uplift of the Sierra Nevada caused existing drainages to cut down through the volcanic Valley Springs - Mehrten sequence and carve deep river gorges into the underlying basement rocks. During this process, the rivers became charged with placer-gold deposits from both newly eroded basement rocks and from the reconcentration of the eroded Tertiary placers. The discovery of these modern Quaternary placers in the American River is what sparked the California Gold Rush. Tertiary Channel Gravels It has been estimated that 40 percent of California's gold production has come from placer deposits along the western Sierra Nevada (Clark, 1966). These placer deposits are divisible into Tertiary deposits preserved on the interstream ridges, and Quaternary and younger deposits associated with present streams. Tertiary gravels can be further divided into basal Eocene, or "auriferous" gravels, which almost invariably rest on basement, and younger "intervolcanic" gravels, which are within the overlying continental volcanic units. Tertiary gravels have been mined chiefly by hydraulicking or drift mining, and the Quaternary deposits by dredging and small scale placer methods (pan, rockers, long toms). After the Jurassic Nevadan Orogeny, the Sierra Nevada was eroded and its sediments transported westward by river systems to a Cretaceous marine basin occupying the area of today's Great Valley and Coast Ranges. By the Eocene, the Sierra Nevada was more hilly than mountainous and of lower relief than present. Low stream gradients and a high sediment load allowed shallow valleys to accumulate thick gravel deposits as the streams meandered over flood plains up to several miles wide developed on the bedrock surface. The major rivers were similar in location, direction of flow, and drainage area to the modern Yuba, American, Mokelumne, Calaveras, Stanislaus, and Tuolumne Rivers. Their auriferous gravel deposits are scattered throughout a belt 40 - 50 miles wide and 150 miles long from Plumas County to Tuolumne County (Merwin, 1968). Bedrock erosion degraded the rich gold-bearing veins as the rivers crossed the metamorphic belts of the Sierra Nevada. Upstream of the gold belts and on the granitic Sierra Nevada batholith, channels are barren, but become progressively richer as they cross the metamorphic belts and the Mother Lode area. Large volumes of liberated gold accumulated in the basal gravels. These gravels were composed largely of resistant quartz and metamorphic bedrock fragments. Considerable siliceous blue-black slate and schist fragments imparted a bluish hue to the gravels, hence the name blue leads or blue gravels. These basal channels have been the most productive as a whole and grade upward into quartz sand and laminated clays. Adjacent to the bedrock channels, broad gently sloping benches received shallow but extensive accumulations of auriferous overbank gravels sometimes 1-2 miles wide.

Comment (Geology): Unlike the extensive tertiary auriferous gravels of the ancestral Yuba and American rivers to the north, little specific information is available regarding the Volcano district deposits of the Tertiary Mokelumne River. This is in part due to their more limited distribution and lower ore grades. The most productive port of the district was near Volcano, where lenses of limestone occurred within schist and slate of the Calaveras Complex bedrock. Locally, the overlying Mehten Formation and Valley Springs intervocalic gravels were removed by erosion, concentrating the gravels on bedrock. Rich gravels were often found in deep potholes eroded into the limestone.

Comment (Deposit): Volcano district produced largely from typical Tertiary auriferous gravels of the ancestral Mokelumne River. While little information is available about the specific placer deposits of the ancestral Mokelumne River, much has been written about the more abundant and productive placers deposited by the contemporary ancestral American and Yuba Rivers in El Dorado, Placer, and Sierra counties. Ores consisted of Eocene channel lag and bench gravels deposited on the eroded bedrock surface and later elevated and exposed by uplift and downcutting of more recent drainages. Throughout most of the northern Sierra, the Eocene bedrock gravels were overlain by recurrent eruptive rhyolitic flows and tuffs of the Valley Springs formation. Between these events, new drainages were established, often scouring into and eroding older bedrock auriferous gravels and incorporating placer gold particles into their own "intervocanic" channel deposits. The best gravels were those deposited directly on bedrock and derived from the erosion of bedrock gold bearing quartz veins. These gravels were recognized by the abundance of quartz and metamorphic bedrock fragments, the latter imparting a bluish cast to the gravels. Deposits included gravels, cobbles, and quartz boulders. Pay zones were commonly erratic, but often meandered from one side of the channel to the other reflecting relict current velocities. Gold particles tended to be flat or rounded and ranged from fine flour gold to large nuggets. A little fine or flour gold was found in the sands and clays that covered the gravels. Younger intervolcanic channel gravels were often barren, and almost always less rich than the bedrock gravels, their gold content being largely a function of how deeply the scoured.

Comment (Commodity): Commodity Info: Placer deposits -gold dust to large nuggets.

Comment (Commodity): Ore Materials: Native gold

Comment (Commodity): Gangue Materials: Quartz and metamorphic gravels

References

Reference (Deposit): Clark, W. B., 1970, Gold districts of California: California Divisions of Mines and Geology Bulletin 193, p. 126-127.

Reference (Deposit): Carlson, D.W., and Clark, W.B., 1954, Amador County, placer gold: California Journal of Mines and Geology, v. 50, pp. 197-200.

Reference (Deposit): Haley, C.S., 1923, Gold placers of California: California Mining Bureau Bulletin 92, pp. 146-147.

Reference (Deposit): Koschmann, A.H., and Bergendahl, M.H., 1968, Principal gold-producing districts in the United States: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 610, p. 58

Reference (Deposit): Lindgren, W., 1911, Tertiary gravels of the Sierra Nevada: U.S. Geological Survey Prof. Paper 73, pp.195-213

Reference (Deposit): Zimmerman, J.E., 1983, The Geology and structural evolution of a portion of the Mother Lode Belt, Amador County, California: unpublished M.S. thesis, University of Arizona, 138 p.

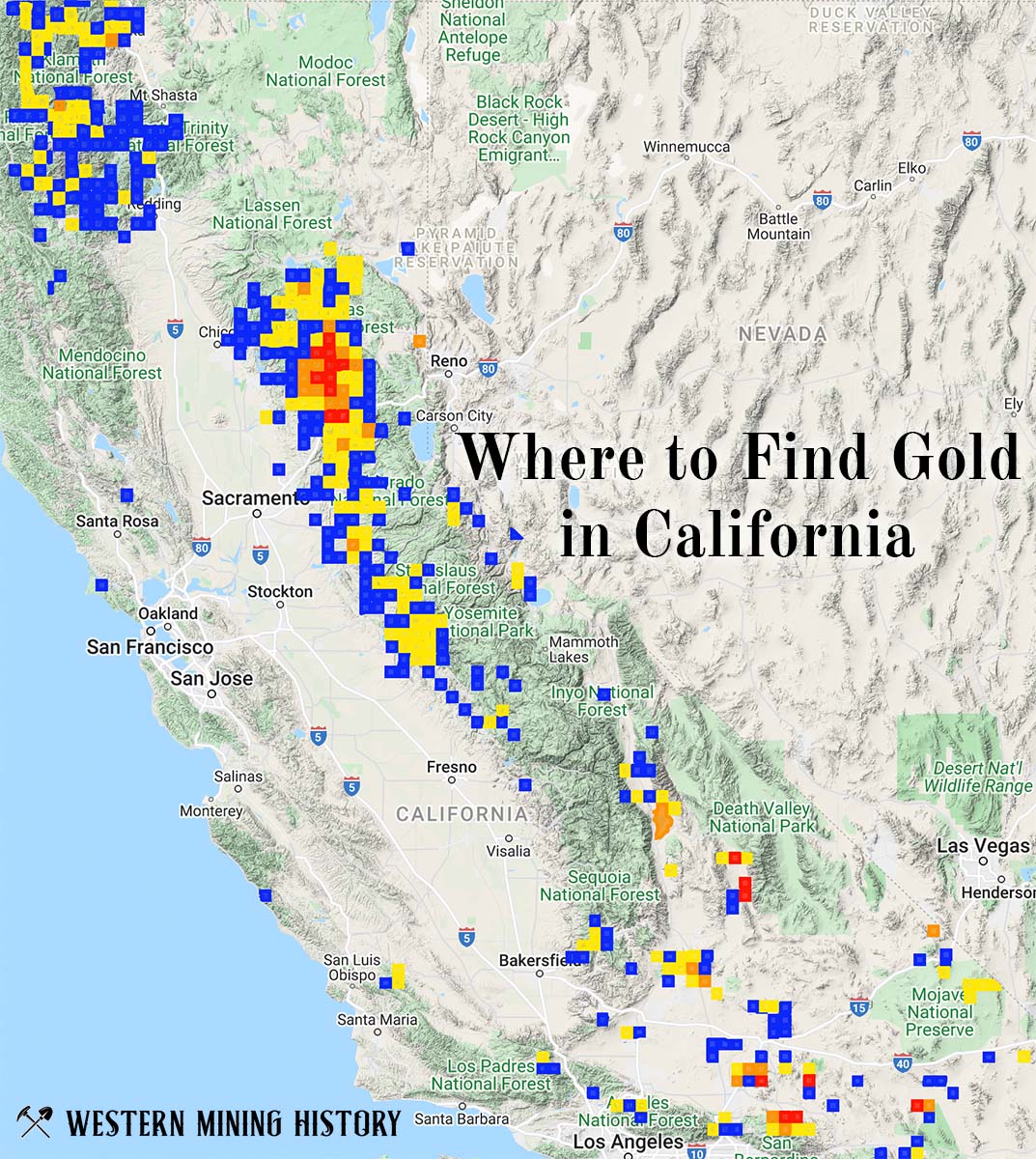

California Gold

"Where to Find Gold in California" looks at the density of modern placer mining claims along with historical gold mining locations and mining district descriptions to determine areas of high gold discovery potential in California. Read more: Where to Find Gold in California.