Kennecott History

By Nick Gentile.

The story of Kennecott began with the discovery of rich ore in 1900, when prospectors Clarence Warner and “Tarantula” Jack Smith spotted what appeared to be a patch of grass high on the mountainside above Kennicott Glacier. Instead of grass, they found copper ore of unparalleled purity. The discovery sparked a rush to extract the wealth embedded in the mountain, transforming the remote site into one of the richest copper mines in history.

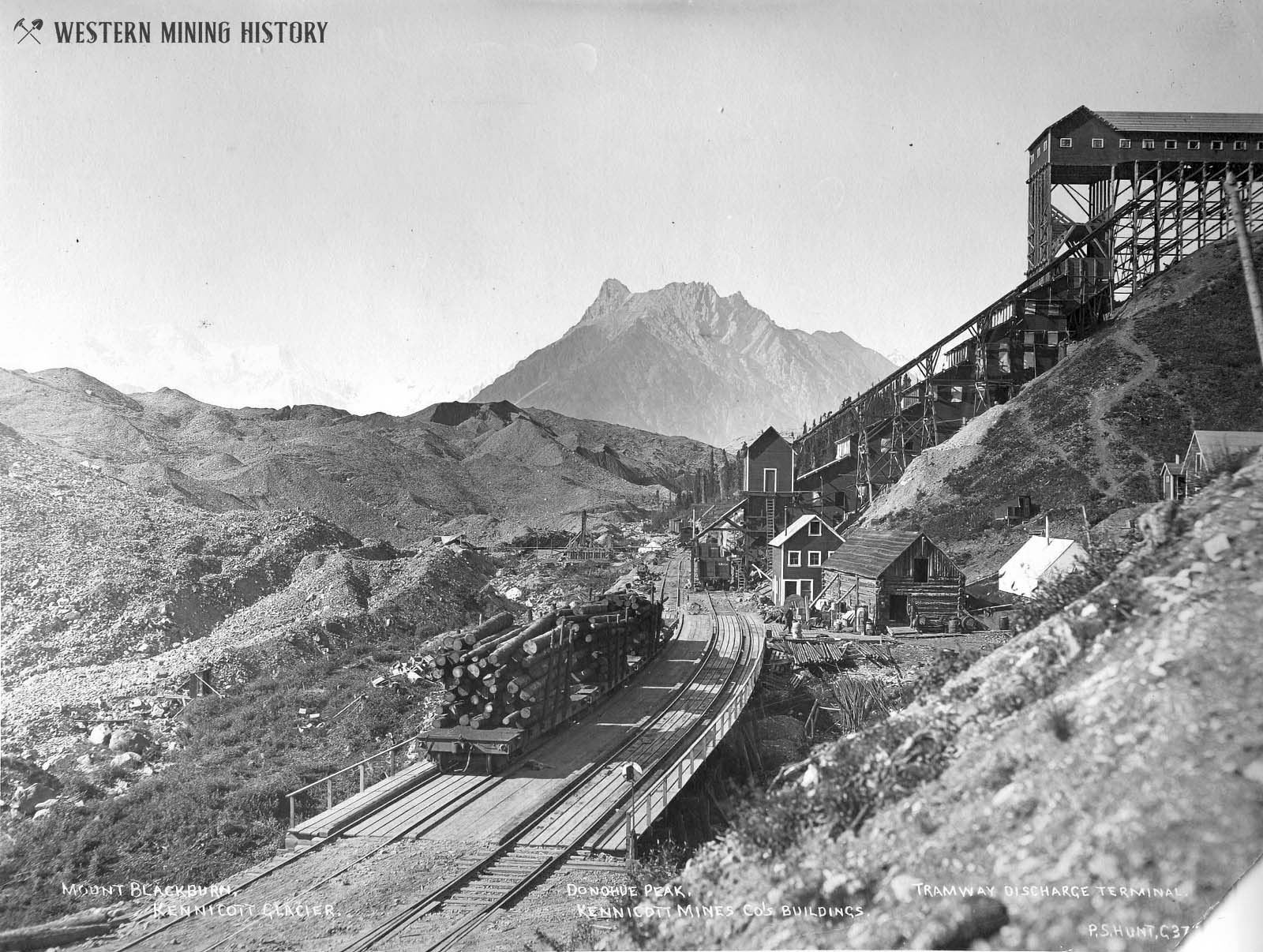

The Alaska Syndicate was quickly formed to develop the site with the backing of investors like J.P. Morgan and the Guggenheim family. Extracting the copper from such a remote and difficult environment required extraordinary feats of engineering. The 196-mile Copper River & Northwestern Railway (CR&NW) was built to connect Kennecott to the port town of Cordova in just two years. Workers faced avalanches, extreme cold, and glacial floods to complete the line in 1911. The route included the Miles Glacier Bridge, aka the “Million Dollar Bridge,” which was designed to withstand massive ice flows each spring from the glaciers upriver.

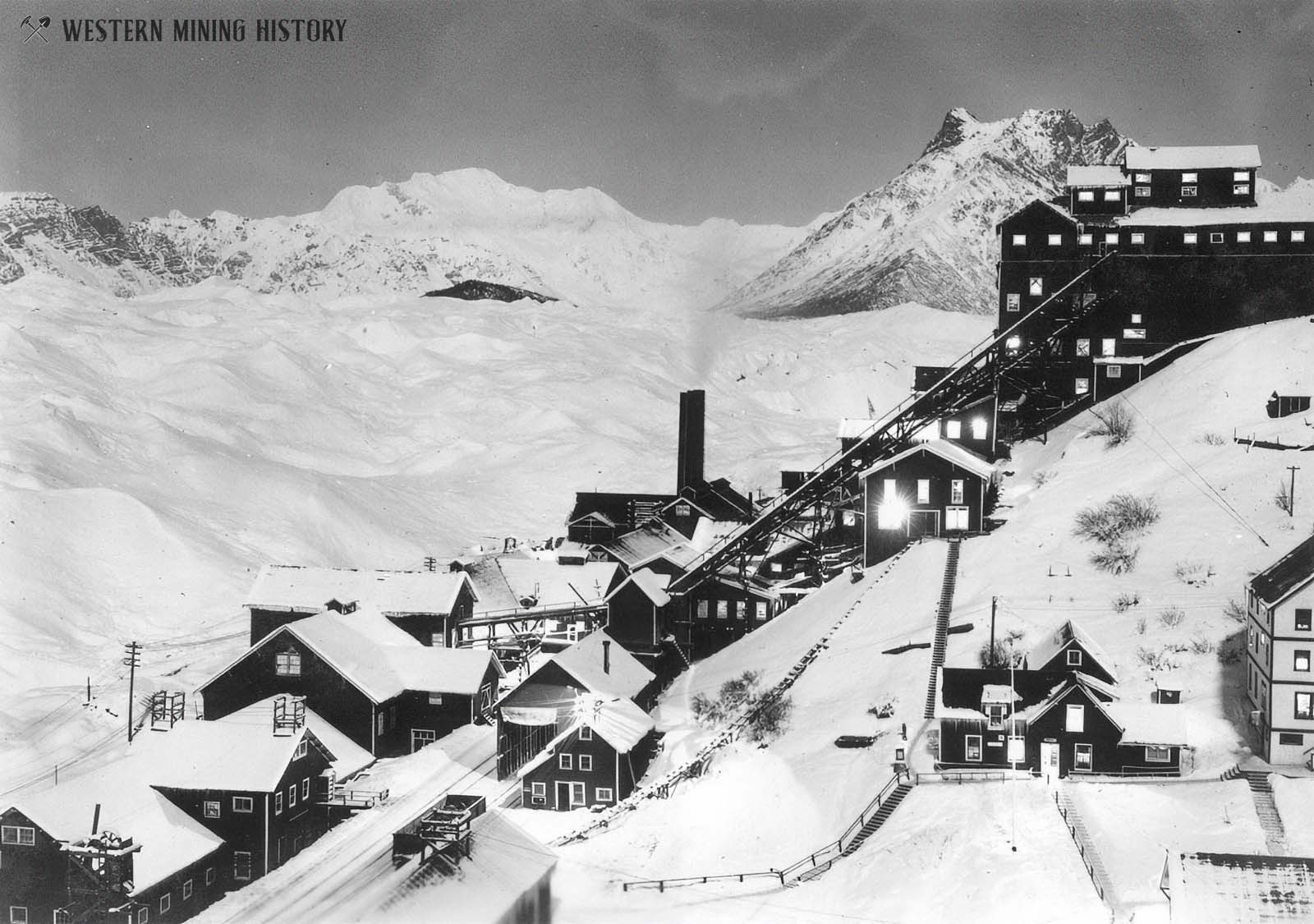

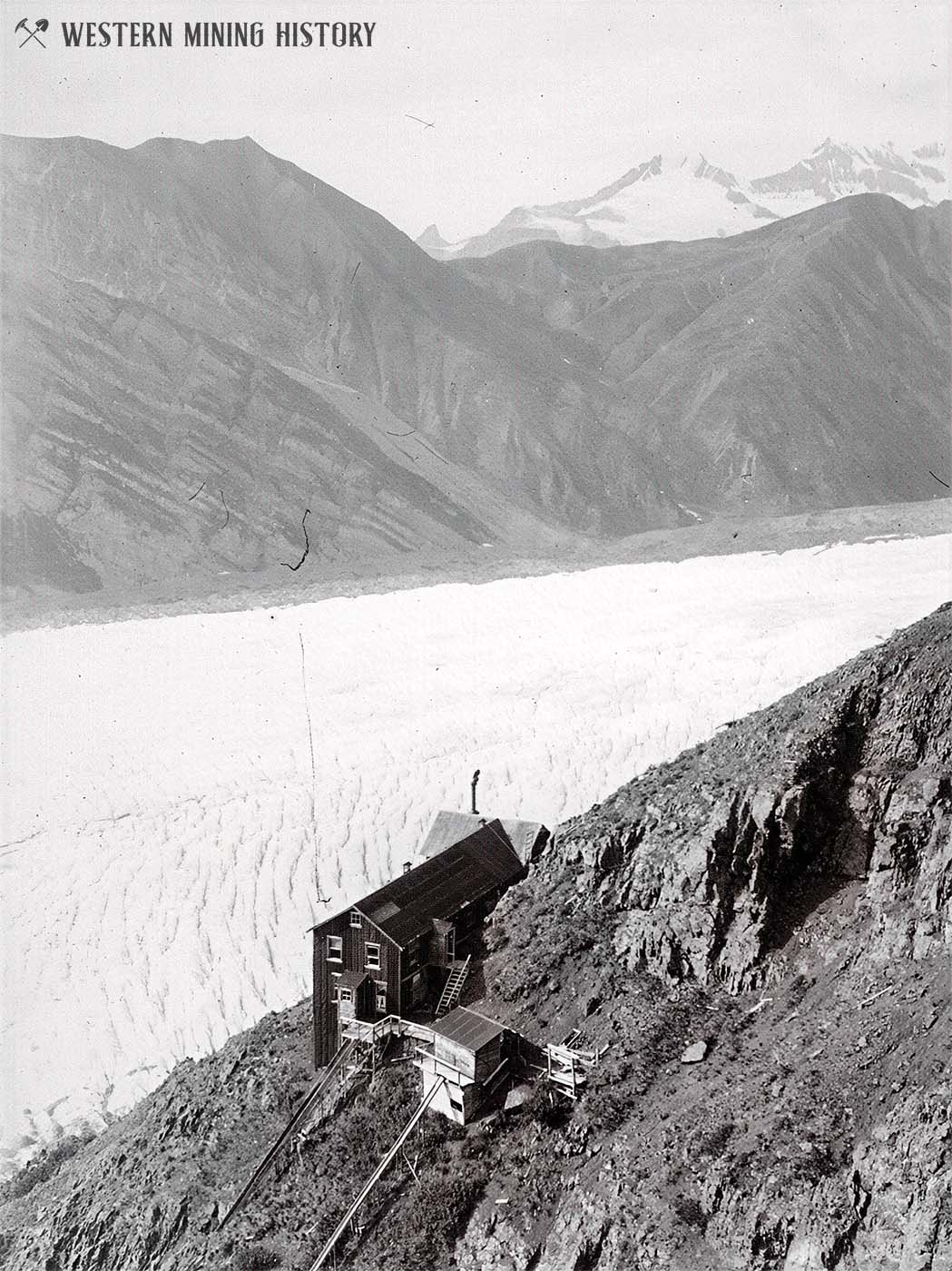

The company town of Kennecott was established adjacent to a glacier deep in the wilderness, with the iconic fourteen-story, ruby-red concentration mill as the centerpiece. Aerial tramways transported the rich ore from mines over 4,000 feet above the valley floor to the mill, where new and innovative techniques like ammonia leaching dramatically improved copper recovery. By the time operations ceased in 1938, Kennecott had produced over 1.3 billion pounds of copper and 280 tons of silver, earning its backers more than $4 billion in today’s dollars.

Life on the Edge

Living in Kennecott was as challenging as it was unique. Although the town was just half a mile long and only a few hundred feet wide, it was self-sufficient with a hospital, school, general store, dairy, and tennis courts.

Winters here were extreme, with temperatures plunging below -50°F and only a few hours of sunlight each day, if it wasn’t snowing. Supplies arrived by train, and the town was entirely cut off from the outer world when the railroad would shut down for repairs.

To unwind, miners traveled to McCarthy, a “vice town” five miles south that offered gambling, saloons, and brothels – none of which were allowed in Kennecott by mine management. McCarthy became a haven for miners seeking respite from Kennecott’s tightly controlled environment. The trains even carried a unique whistle to warn saloons when a US Marshal was onboard.

Despite the challenges of living in this remote location, Kennecott fostered a vibrant community. Families planted gardens, organized baseball games, and held school events each year. Children of the town were given a lot of freedom to play and explore. Workers from around the world created a melting pot of cultures, forming close bonds in their shared isolation. Most of the miners were from Scandinavian countries, but Cornish miners from England were also common.

Decline and Abandonment

Kennecott’s decline began in the late 1920s, as copper prices plummeted during the Great Depression. With no new significant ore deposits discovered for several years, the mines struggled to remain profitable. The entire operation closed for several years in the early 1930s, then reopened for a few years until finally shutting down for good in late 1938. On November 11, 1938, the last train left Kennecott, carrying its final residents to the port of Cordova.

For decades, Kennecott sat abandoned, its buildings slowly deteriorating and left in disrepair. In 1986, it was designated a National Historic Landmark, and in 1998, the National Park Service acquired much of the land in and around the town. Restoration efforts began, stabilizing key structures like the concentration mill and addressing environmental contamination. Kennecott has since become a centerpiece of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, the largest of the United States’s parks, and draws visitors from around the world.

Kennecott is more than a relic; it symbolizes human determination and ingenuity. It represents both the triumphs of early industrial innovation and the costs of resource extraction in a fragile wilderness. Walking through its quiet streets today, with the red-painted buildings standing stark against the icy landscape, visitors can imagine the lives of those who braved the elements to turn a remote patch of Alaska into a thriving town. Kennecott’s copper still powers much of the modern world, a silent reminder of the ambition and sacrifice that once brought this frontier to life.

Author Nick Gentile's video provides a longer history of Kennecott: Kennecott, Alaska - A Gem of the Northern Frontier

Copper and Community: Life at Kennecott

During the 1990s, three separate reunions were held at the Kennicott Glacier Lodge that brought together the school-age children and adult laborers that lived at Kennecott during the 1920s and 1930s. The interviews that were conducted at these events provide a rare and fascinating look into life at one of the West's most remote mining camps. Continue reading... (members only content)