Text By Gary Carter

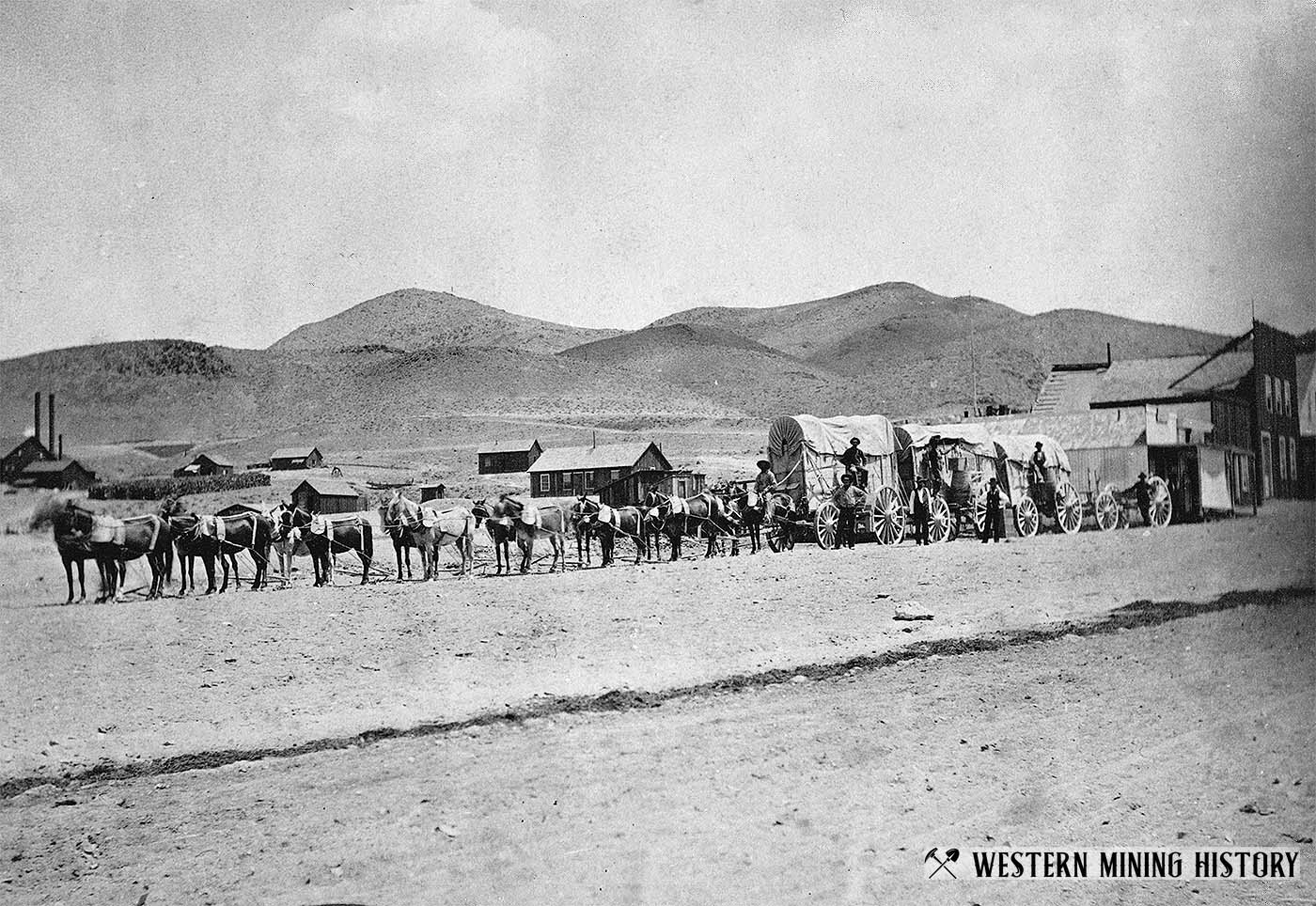

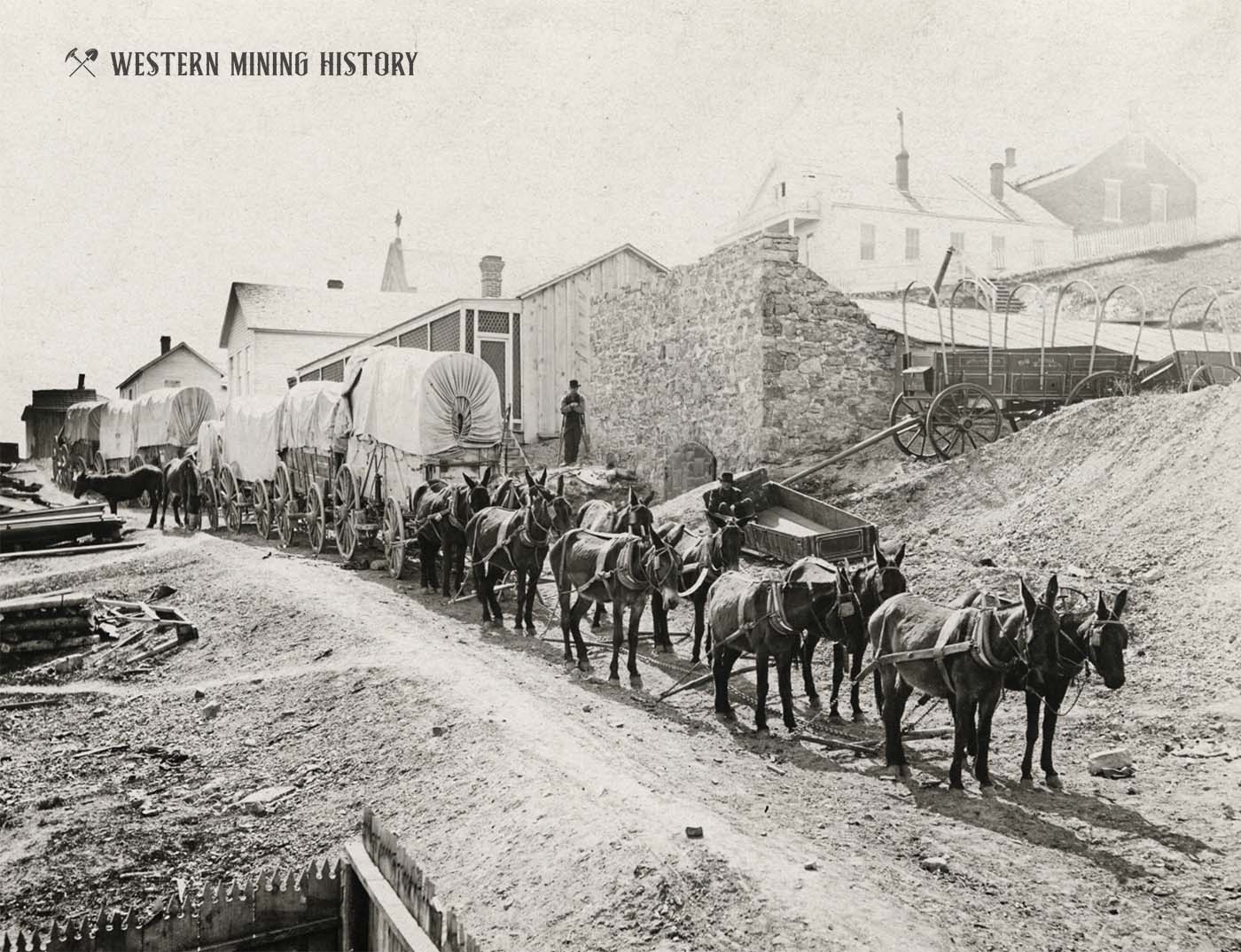

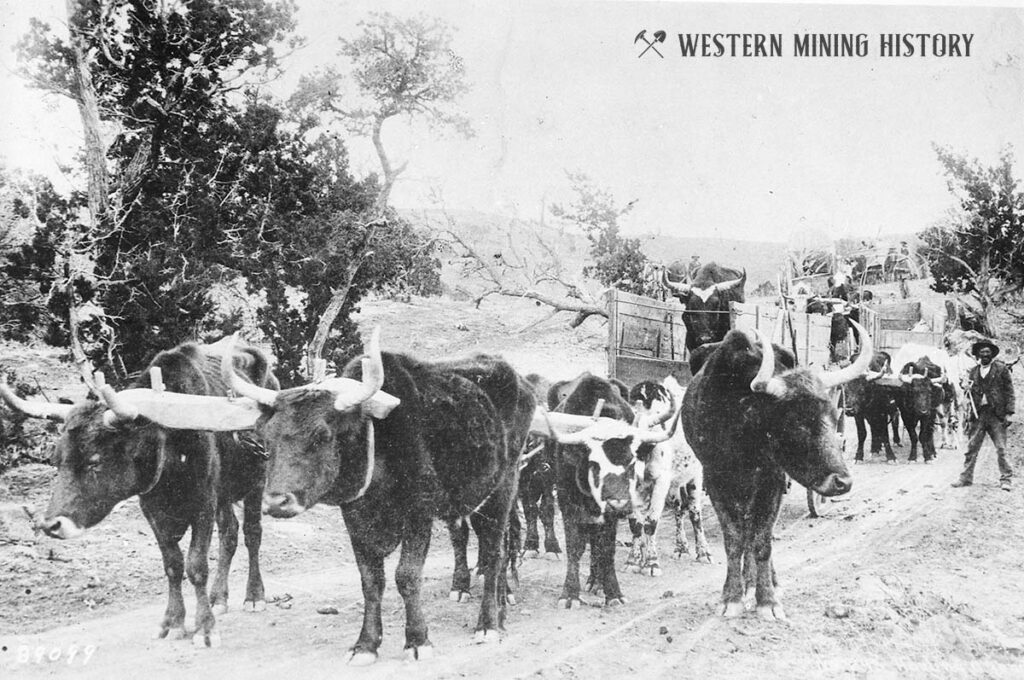

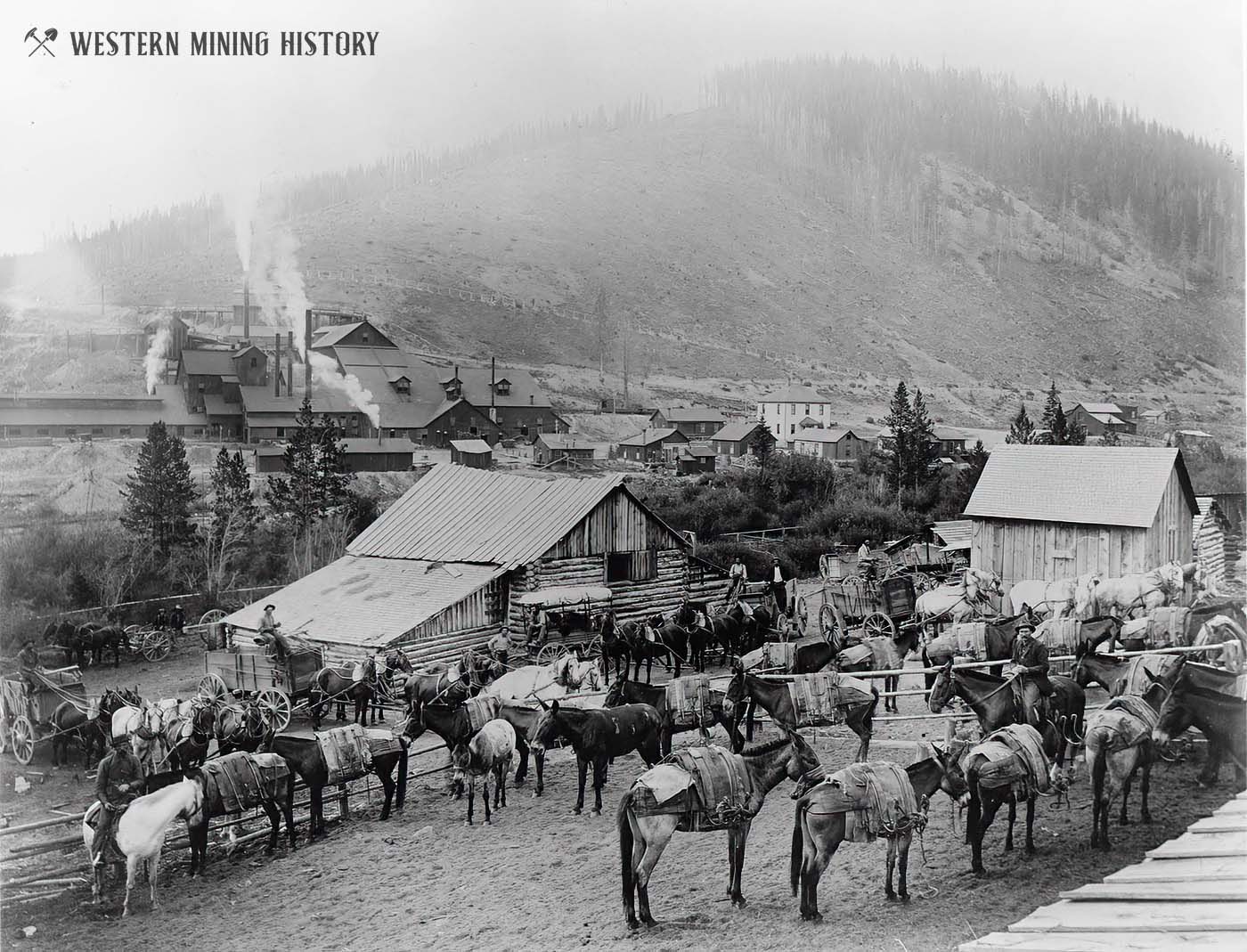

Photos sourced by Western Mining History from various archives.

Author`s Note

Twelve billion tons of freight were transported by truck in the United States last year. The skilled drivers have CB contact, radio, headphones, paved roads, power steering, sleeper cabs, and comfortable seats. Truck stops provide food, showers, and fuel.

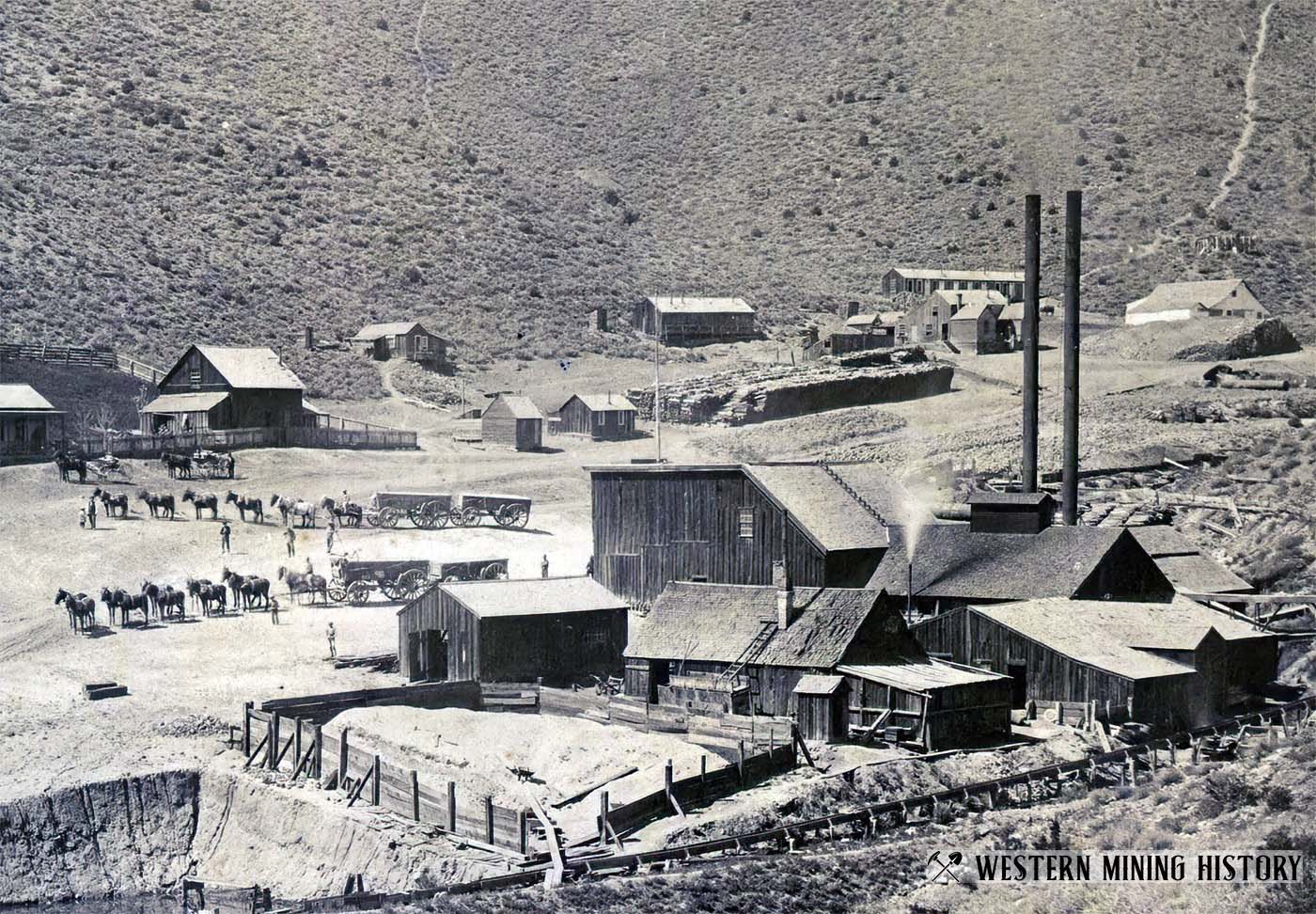

One of the least appreciated but important jobs during the era of the western expansion was moving freight to provide everything from food to machinery, household goods, ore, and needed equipment for the rancher, miner, farmer, households, and storekeeper. Yet the “mule skinner” or “bull whacker” ranked near, if not at the bottom, on the scale of importance in stories about the old West, and even during their time they were looked down upon.

This article will provide a snapshot of the operation and men (mostly) of early freighting in the period before wheeled vehicles. The use of steamboats on navigable waters in the west, and the steady growth of railroads from the 1840’s well into the latter part of the century provided a huge slice of the freight transporting business, but those modes generally reached cities and large towns, off loaded and needed to be transported.

The focus of this article is on heavy duty freight wagons. Light weight express wagons, farm wagons, “Prairie Schooners“ and Conestoga wagons typically used along the trails heading West, military supply/escort wagons, and stage coaches will not be addressed. I hope readers will be as surprised, interested and entertained as I was doing the research.

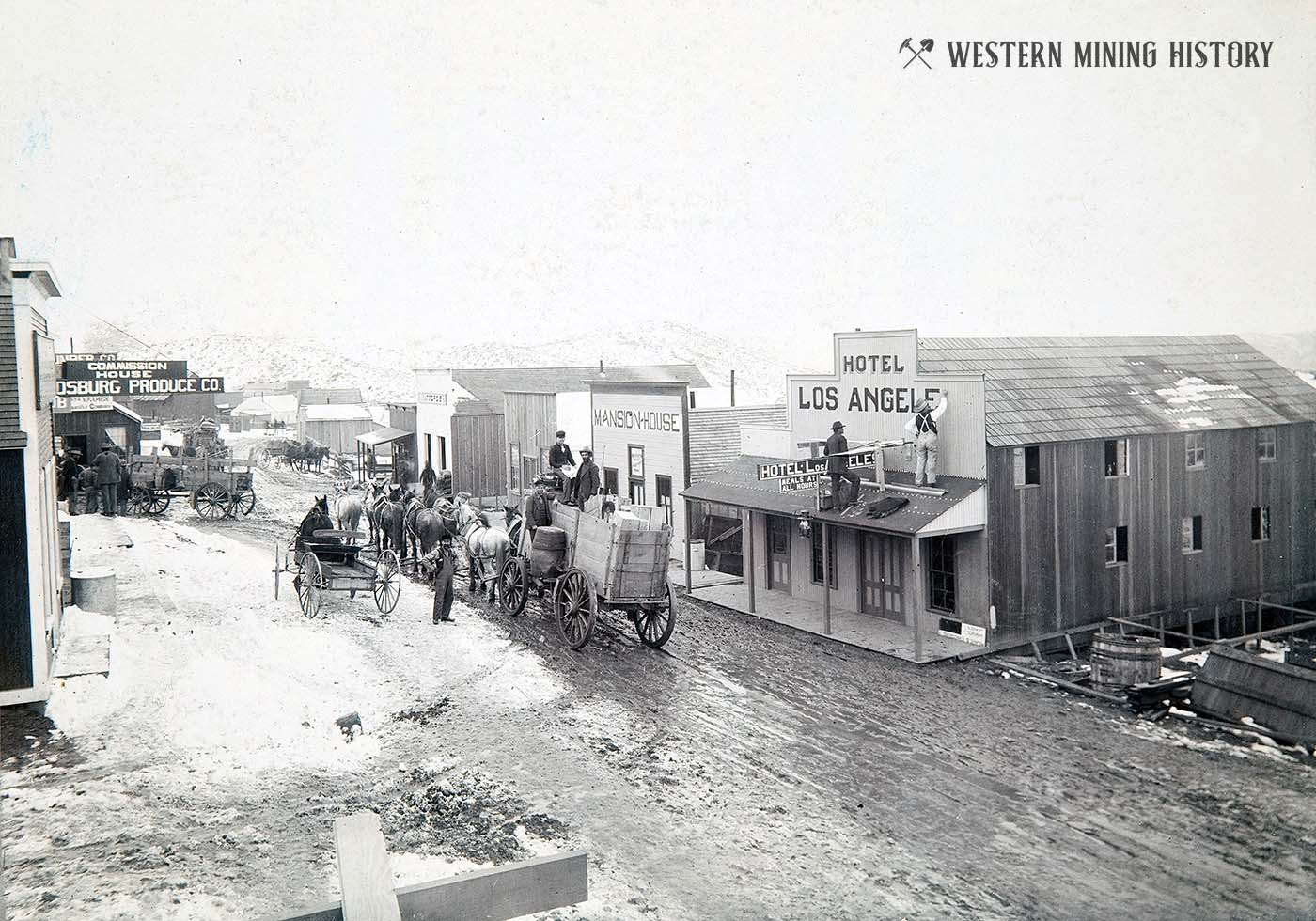

The Freight Companies

Sometimes the scope of things really doesn’t change that much. Just as today, in the early days (up to 1900), there were large freight companies and plenty of independent operators who saw a need to earn a living transporting goods.

Some of the larger companies in the Western States were: The Miller Brothers Freight Company in Arizona, Charles T. Hayden’s Freight company, which had a wide range of coverage. Russell, Majors, and Waddell, while starting in the Great Plains eventually grew to ship goods throughout the west via Santa Fe. Ketchum’s Fast Freight Line served most places in Idaho.

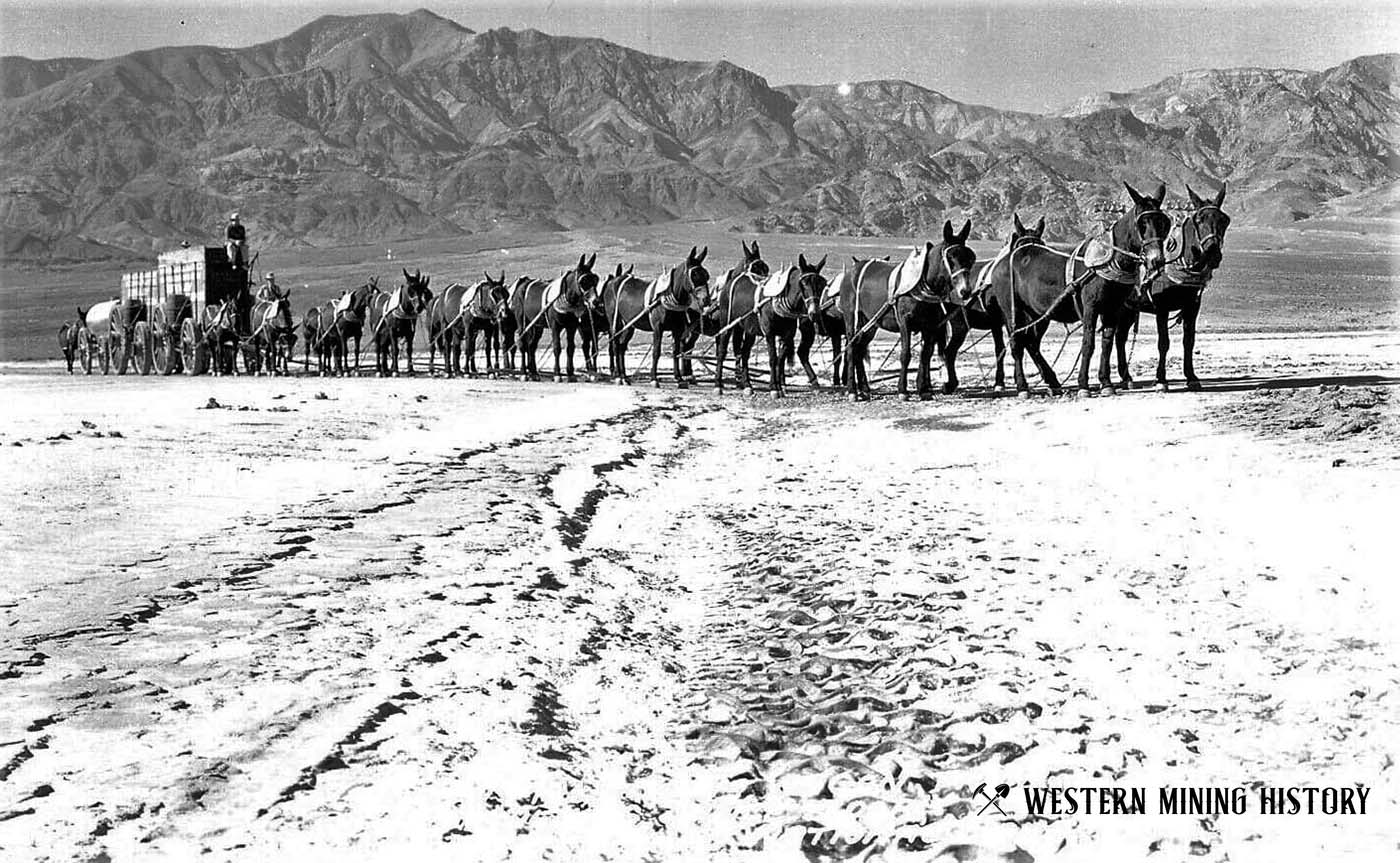

Frank Shaw had a large freight operation that supplied many towns and mines in eastern California and western Nevada and hauled out the first Twenty Mule Team borax wagon load from Death Valley.

Remi Nadeau was known as the king of the Desert Freighters and his company regularly moved goods from Los Angeles to Salt Lake City and Virginia City, Montana. In the late 1860’s Remi Nadeau and Mortimer Belshaw, part owner of the famous Cerro Gordo silver mine, combined to operate the famed Cerro Gordo Freight Company which served most of California and clear into New Mexico.

During the California Gold Rush, mining camps were often so remote and difficult to reach that pack trains of mules carried supplies and much of this was done by individuals. By the mid 1850’s some trails were sufficient to be attempted by wagons, and Phineas Banning and David Alexander formed a freight company which supplied many camps. Their livestock included over 500 mules and horses capable of hitching to forty or more wagons.

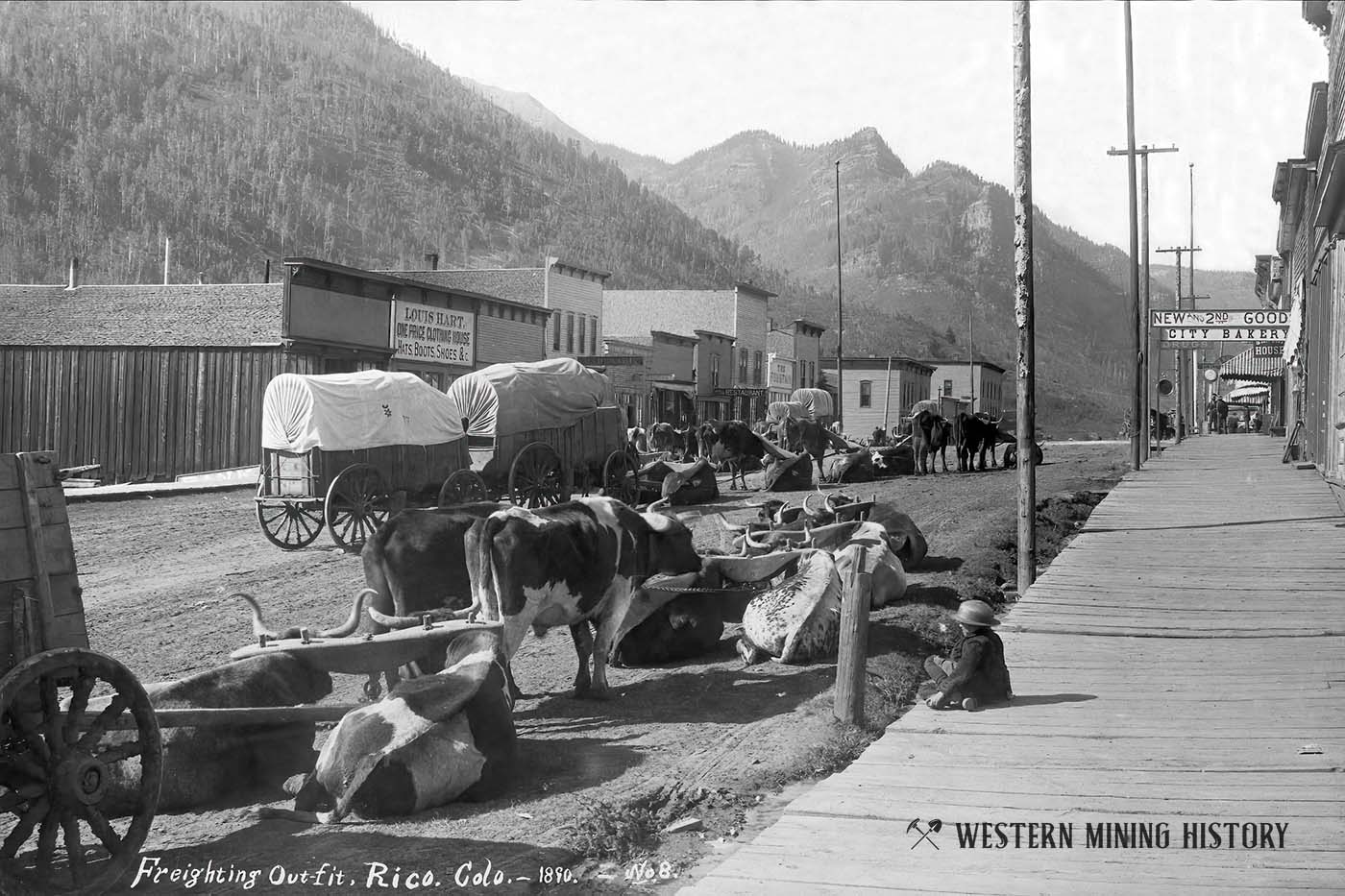

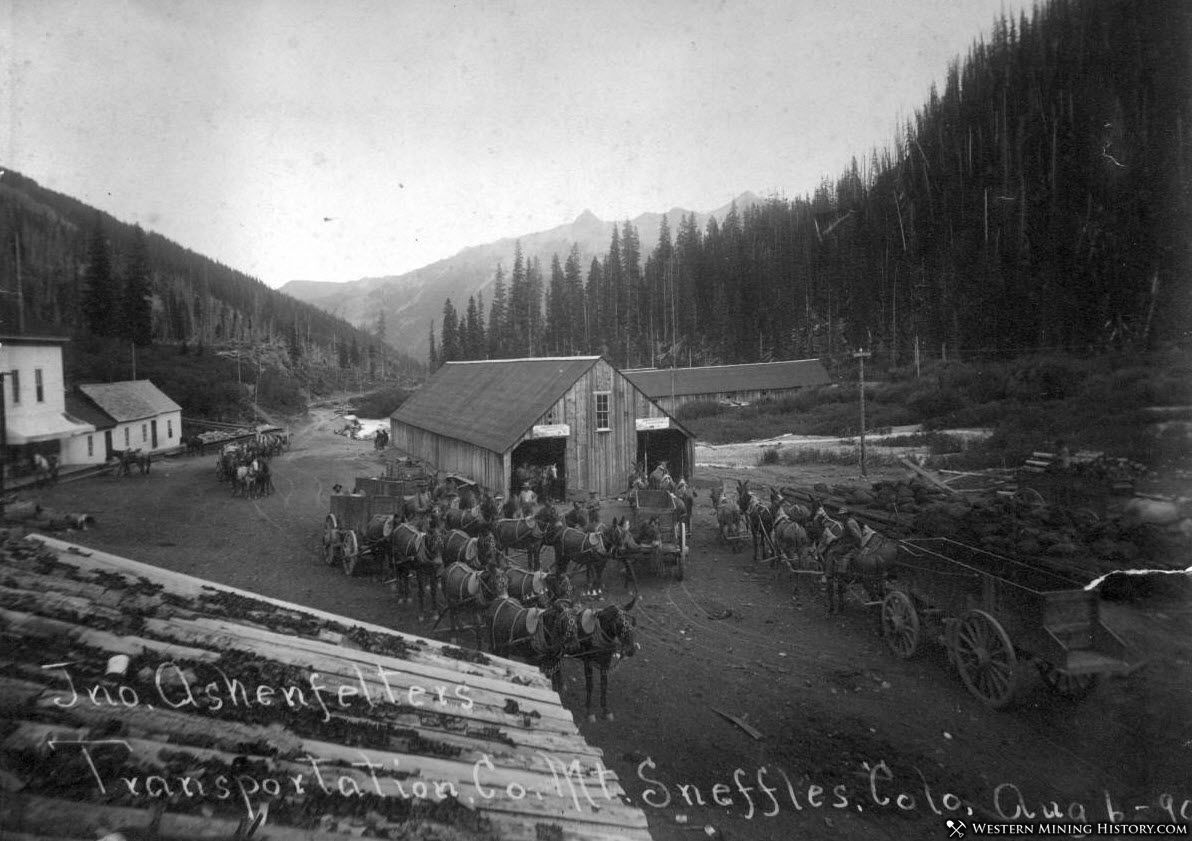

In Colorado, especially in the rich San Juan Mining District, John Ashenfelter ran a large pack train and freighting company that supplied the towns and mining camps, and along with Dave Wood were the largest freighters into Southwestern Colorado towns and mining districts.

These are just a few of the larger freight companies. On a smaller scale were the independent and often lone teamsters who took on the contracts too small, dangerous, or remote for the larger outfits to bother with.

Mule Skinners and Bull Whackers

Depending on your team of animals those who drove the freight wagons were called mule skinners or bull whackers. The mules, of course were not skinned, but the “bull whackers” did have long whips with which to “urge the oxen along”.

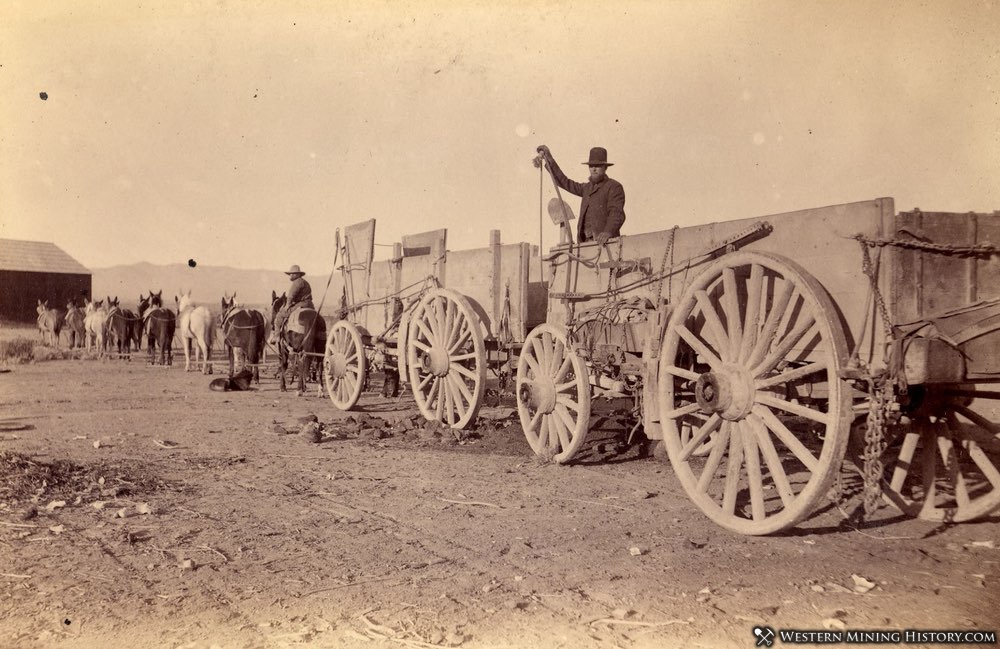

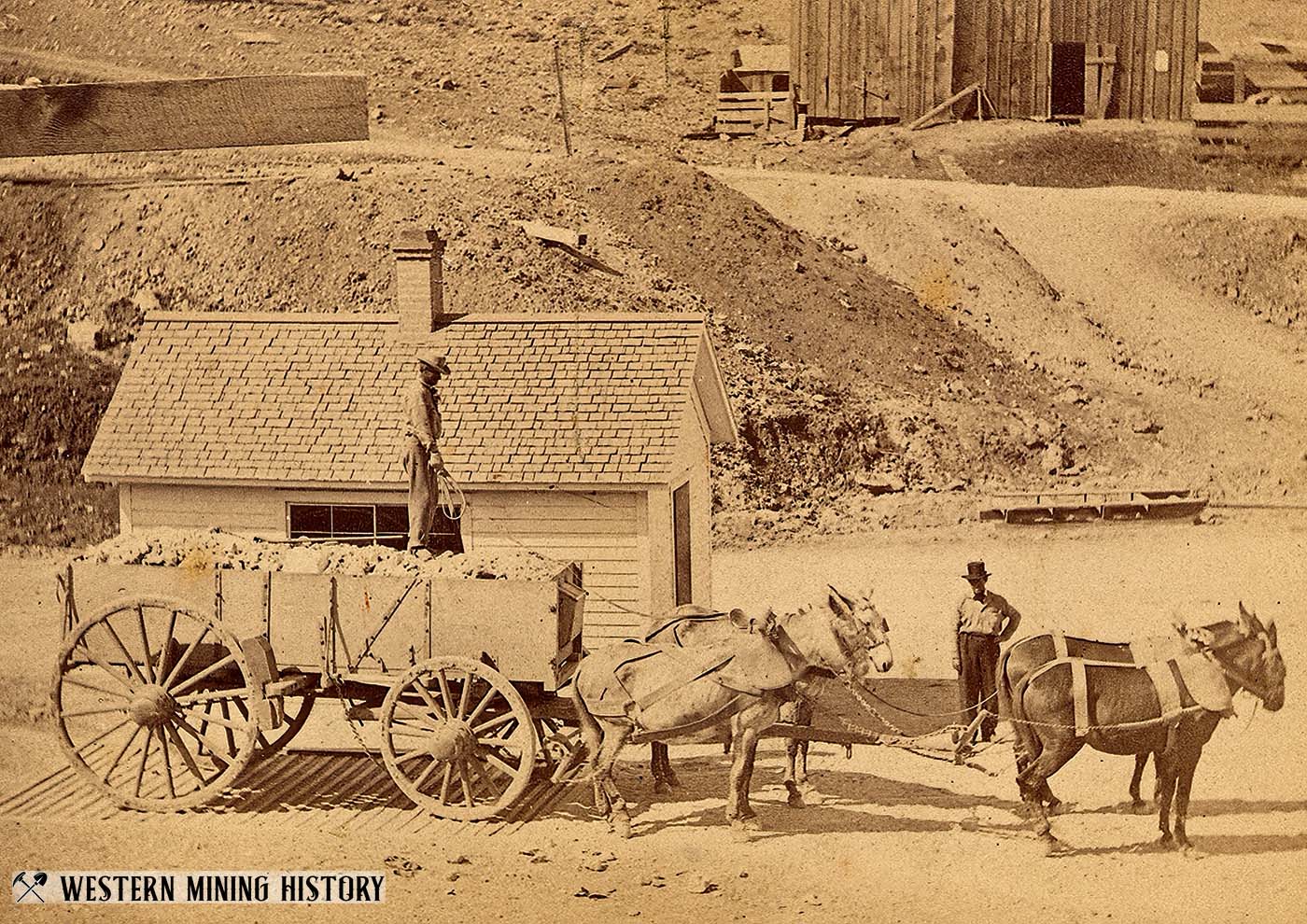

Typically drivers were loners, and might go days without seeing another human, a bath, decent food, or necessities. They slept in the open or under the wagons and most often the larger wagons, especially the ore wagons, had no place to sit, so the freighter rode on the last animal that was in harness or yoke. Some of the wagons had wooden bench seats but men often walked since it was easier on the body than the bouncing of the wagon.

There were often no way stations, no pull offs, no places to safely seek shelter. Up until around the mid 1880, Indians were a menace and quite eager to attack a lone freight wagon and take the animals and goods.

The teamsters usually traveled light carrying a hat, knife, rifle, and the clothes they wore including heavy boots. A rough and ready group, full of profanities and lack of social etiquette, their work day began early and ended late – taking care of the animals and feeding themselves. John Bratt, a bull whacker, said he only ever knew one who did not chew tobacco, swear or drink.

Their life on the trail and vices generally meant most were single and when they did have free time it was often spent on booze, gambling, and soiled doves. The pay of around $70-$80 a month for an experience hand was above that of common laborers or miners who generally got from $2.00-$3.50 a day. To put that in perspective, before the Civil War soldiers (privates) stationed in the West received no more than $15 a month.

A typical charge to haul freight might be $8 to $10 per one hundred pounds but also depended on distance, dangers and difficulty. Large companies with many outfits on the road could do quite well. Russell, Majors and Waddell wagons once made $300,000 on one trip carrying supplies for the army.

The Earp brothers were often engaged in the freight trade, taking turns as “swampers” (helpers who generally assisted in loading and unloading) and drivers.

In deliveries to towns of any size there often was an area of town where the needs of the freighters, such as reshoeing and repairs, could be obtained. More often, especially on lonely, isolated stretches, the swamper and driver performed the chores. Fortunately the wagons were so carefully and sturdily built that despite the difficult conditions serious breakdowns were infrequent.

The Animals

As you might imagine the most important aspect of the trade were the animals. Oxen, mules, and horse were all put in harness and each contributed their own advantages and disadvantages.

Oxen were much cheaper to buy (a pair for about $65 in the mid-1880’s) and could pull considerable weight. They needed less water and feed and often foraged off the land but were much slower than horses and mules. Travel by oxen was at an average of about two miles per hour, which was one-half to two-thirds the speed of a horse or mule.

Big steers with horns were generally the choice for “oxen” with Texas “long horns” or big Durham’s often used. Horns helped to brace the steer on both the up and down hill. The bull whacker chose his stock with care and an experienced eye, not only because of cost but his safety and livelihood often depended on it.

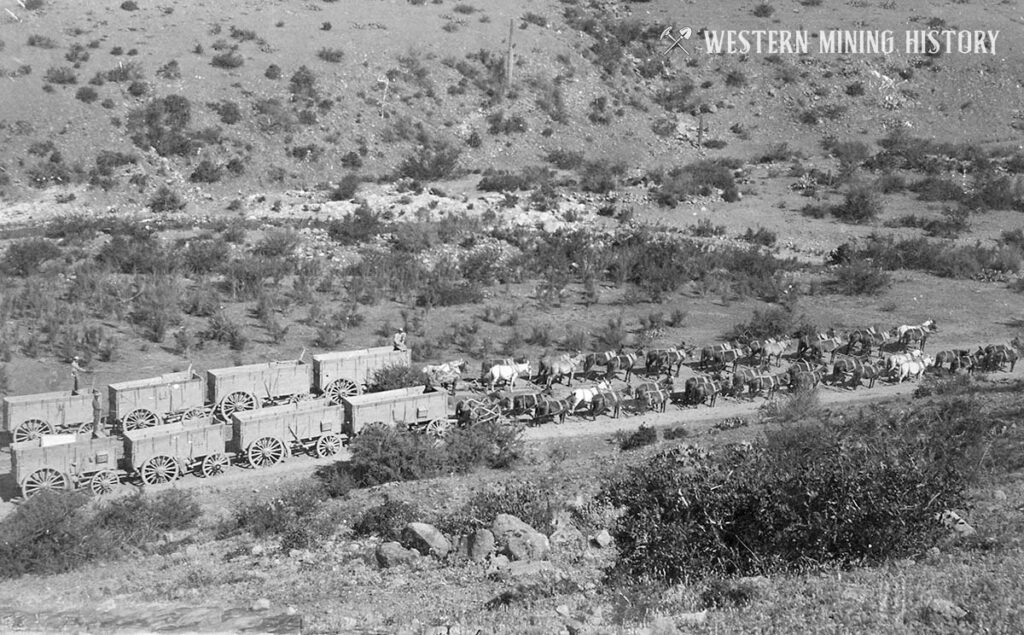

Horses and Mules were expected to pull their weight, thus the etymology of the phrase – “to pull your own weight”. A large mule or horse was typically judged to be able to pull one ton.

Wagons were loaded according to the number of horse or mules needed. A big mule could pull more than a ton and more than the average size horse. Mules and horses were more expensive than oxen with a pair of mules costing about $50 more than the average price for two horses (about $100-$150 in the mid 1800’s).

These animals could cover more ground than an oxen team but needed good feed and more water, which was not always available, especially in the Southwest. Mules and oxen were sure footed and often used over rugged and narrow terrain.

The Wagons and Freight

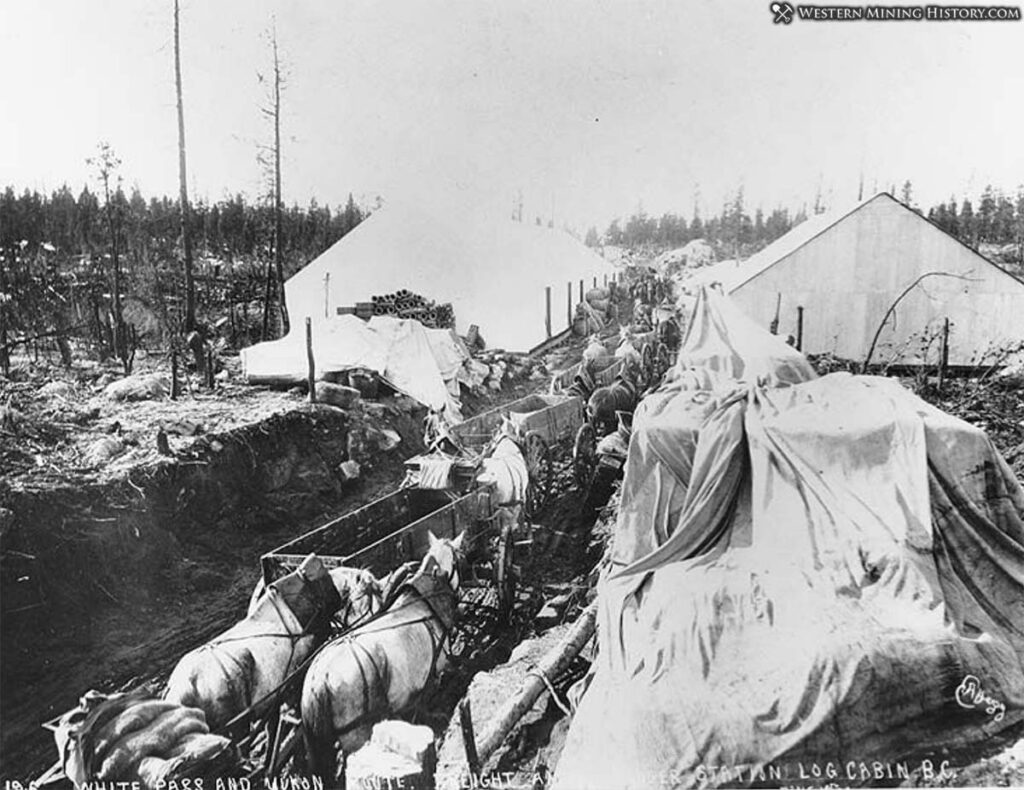

The immediate challenge was terrain, and the word “path” really speaks to the early routes covered by the big freight wagons more than calling them roads.

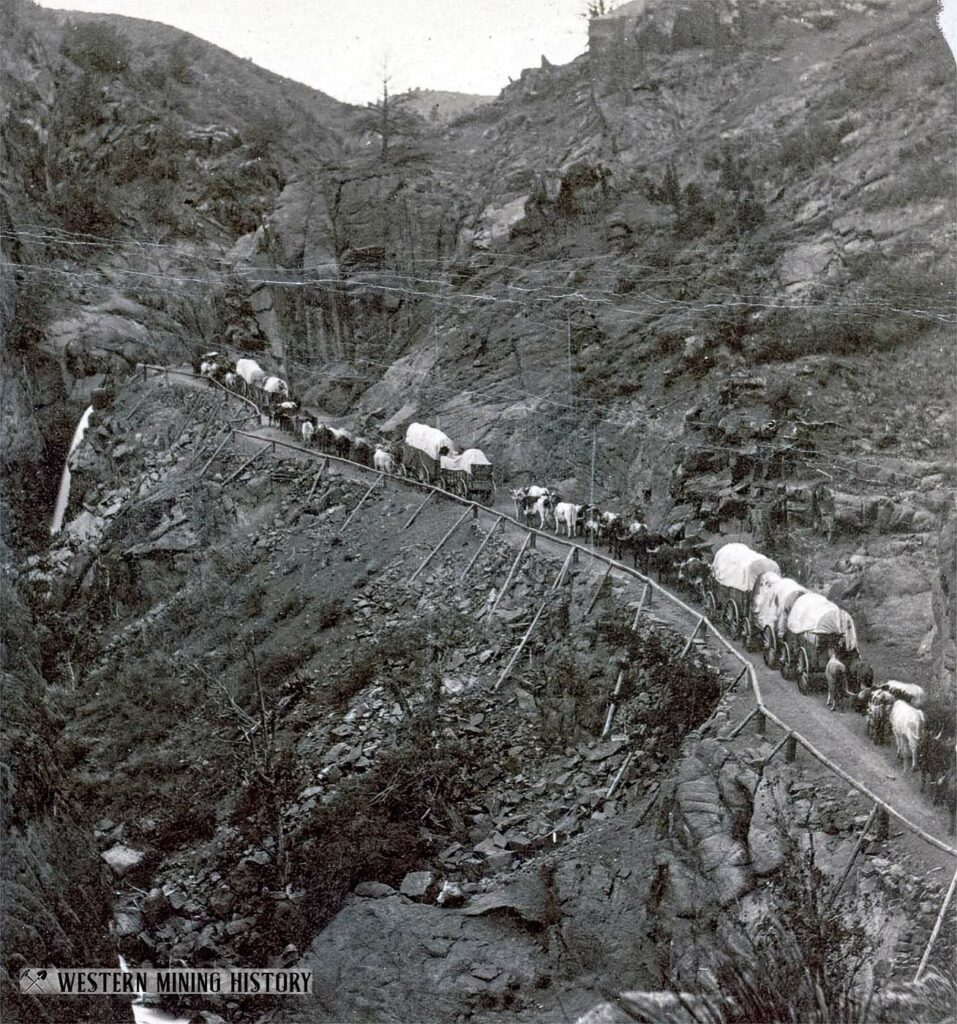

Rocks, washes, drop offs, mud during rainy weather, slides, dust, steep, treacherous climbs, narrow one-way paths and brake burning descents were the conditions that the driver and wagon needed to negotiate. Usually the only “road maintenance” was continued use which often rutted the trail.

Today it often takes an all-terrain vehicle to reach some of the abandoned towns and old mining camps that were serviced by pioneer freight wagons.

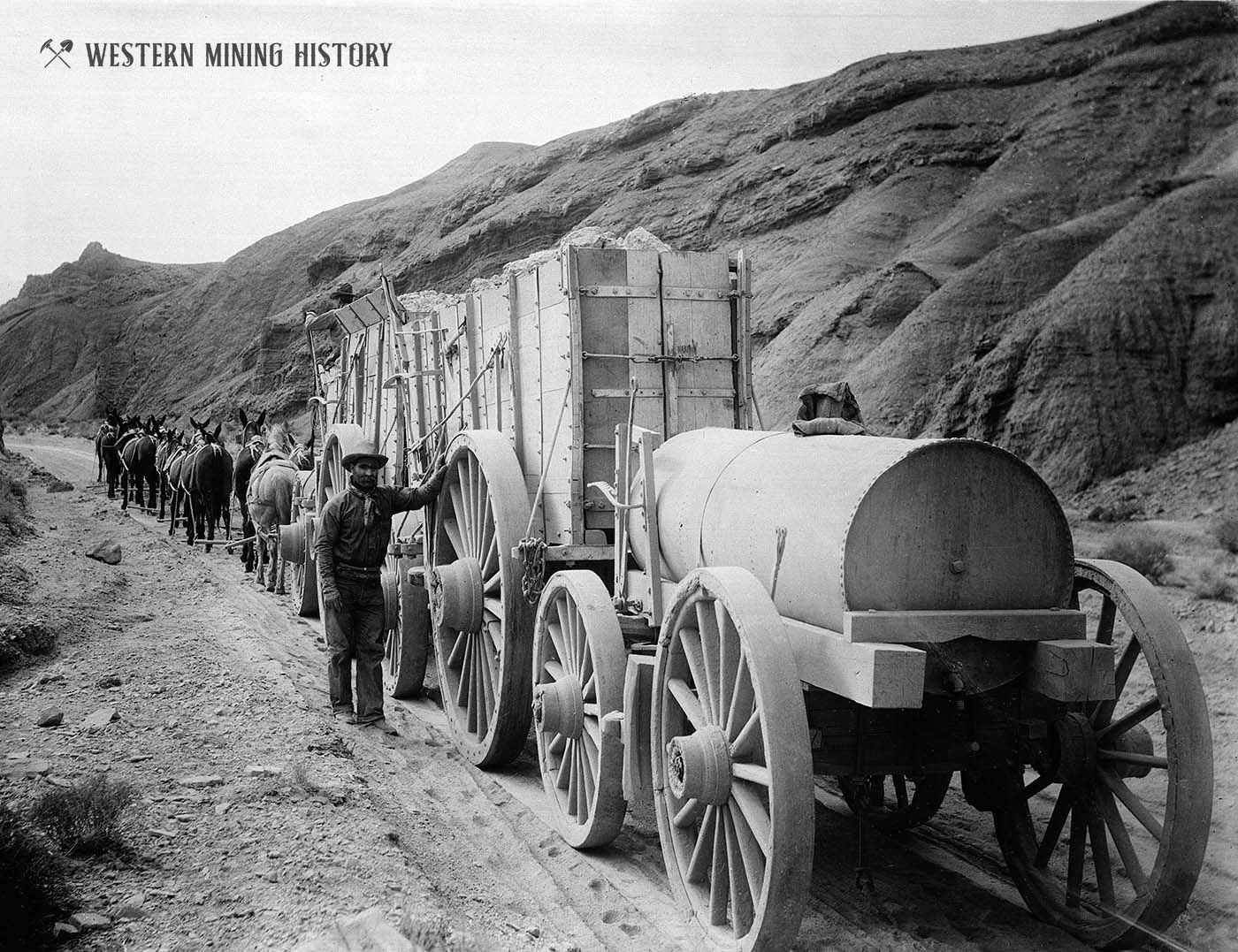

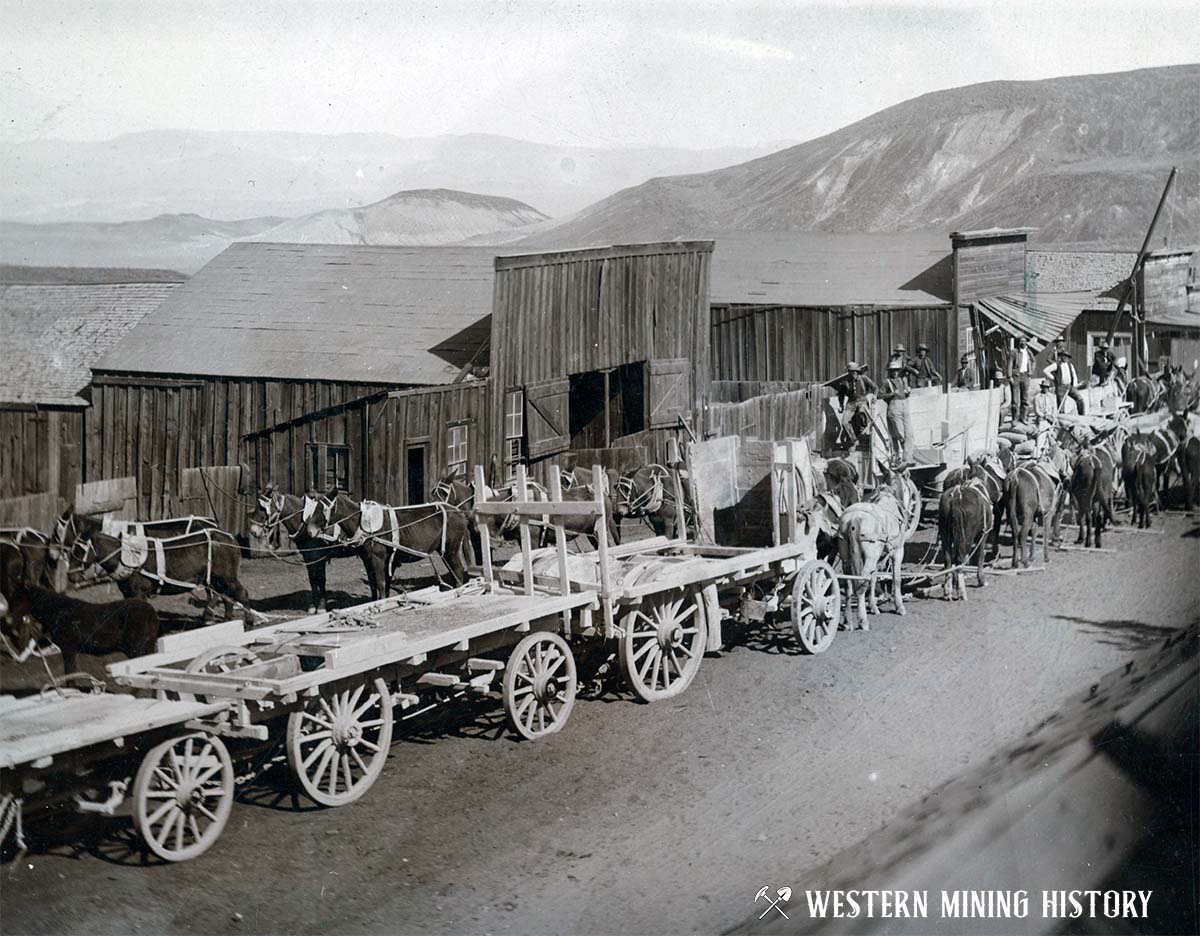

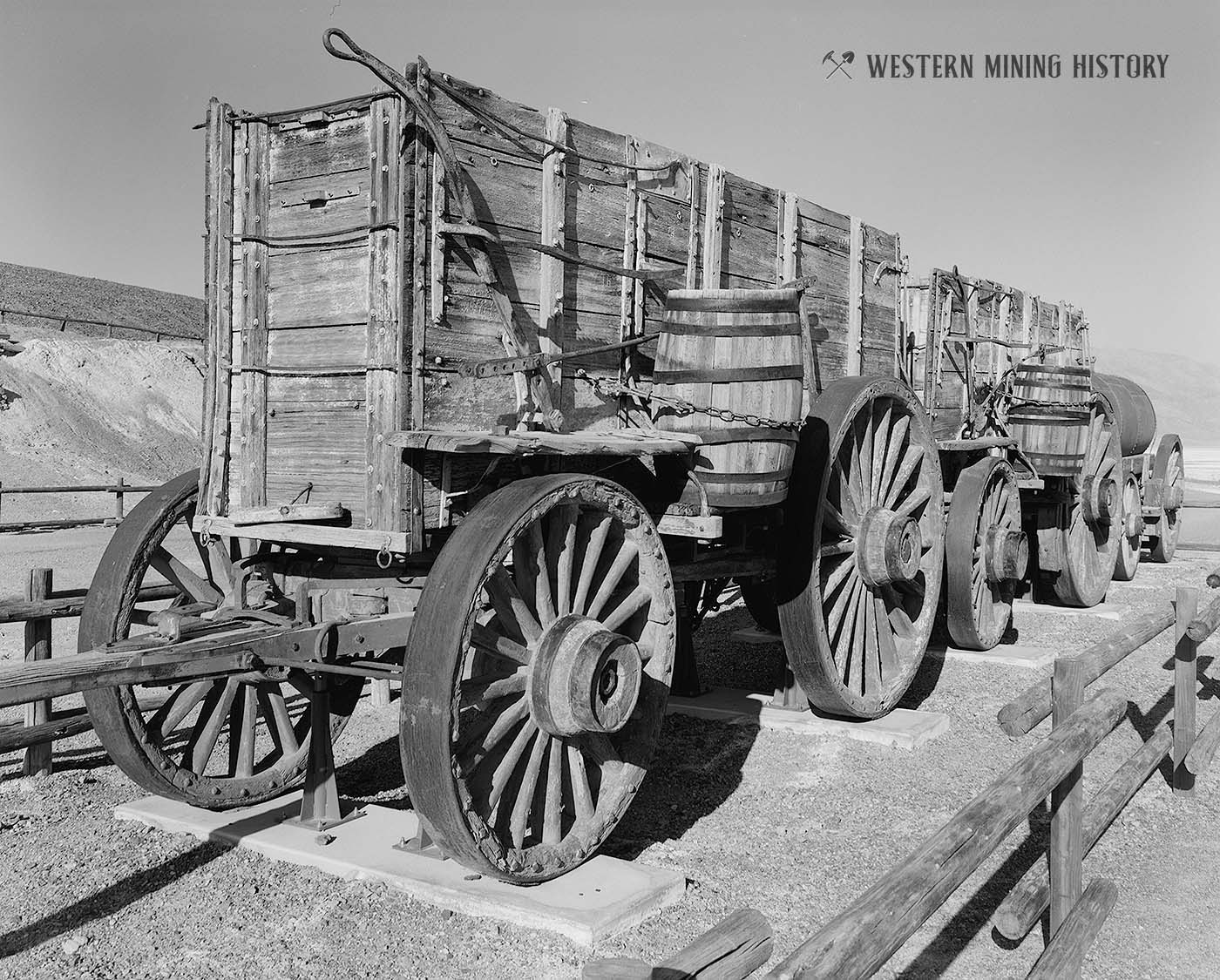

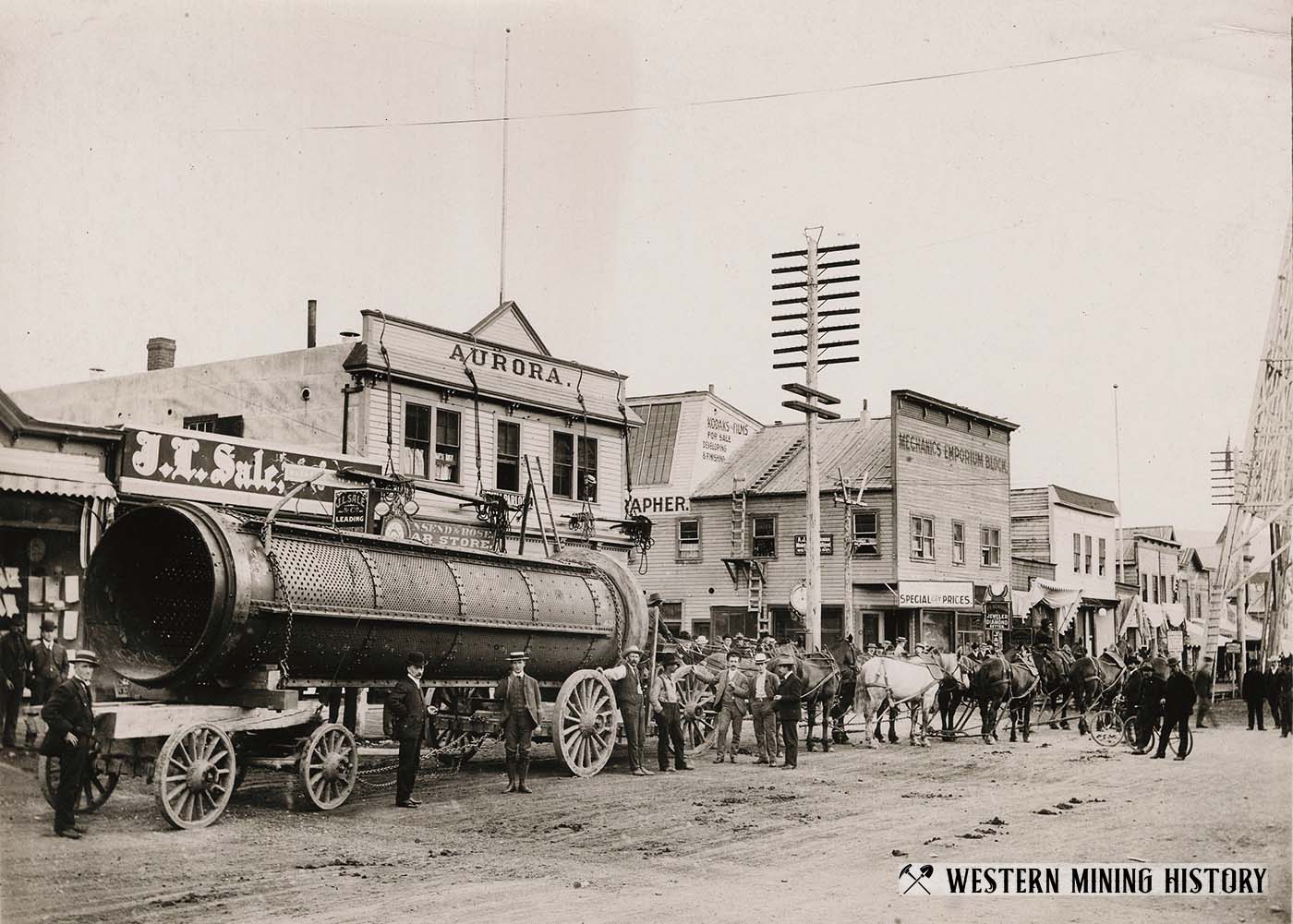

Of necessity, the wagons were built for endurance, durability and carrying capacity. Under carriages were made of iron and the beds and wheels of oak or other durable wood. Dimensions varied, but empty wagons weighed from one ton up to the nearly 8,000 pounds for the big 20 Mule team Borax wagons which operated out of Death Valley.

Freighters, depending on size and need usually hauled from three up to thirty plus tons of cargo.

The big Twenty Mule Team borax wagons that operated out of Death Valley were some of the largest at Sixteen feet long, four feet wide and six feet deep. They carried over thirty-five tons when loaded and had seven foot high rear wheels. Their customary route was from what is now the Furnace Creek Ranch area to the railhead at Mohave, some one hundred and sixty miles through the desert. It was generally a ten day trip.

Overnight travel required the teamster to make provisions to carry water for himself and animals and perhaps feed as well. On long trips in dry areas or places with few streams, it was impossible to carry enough water so drivers needed to be aware of and plans stops at known springs and water holes.

Stream crossings, especially in the spring, were traversed with great caution as unseen rocks, deep spots or an eroded soft bottom could cause problems for the animals and wagons. Likewise steep uphill grades often required the unhitching of one team and using it to help the other ascend and then repeating the process for the other wagon.

On one trip from Prescott to the Pima Villages in Arizona, the driver waited several days for the Gila River to recede and when it did not he built a raft, unloaded the goods, poled them over piecemeal and then drove the team and wagon across, reloaded and was on his way.

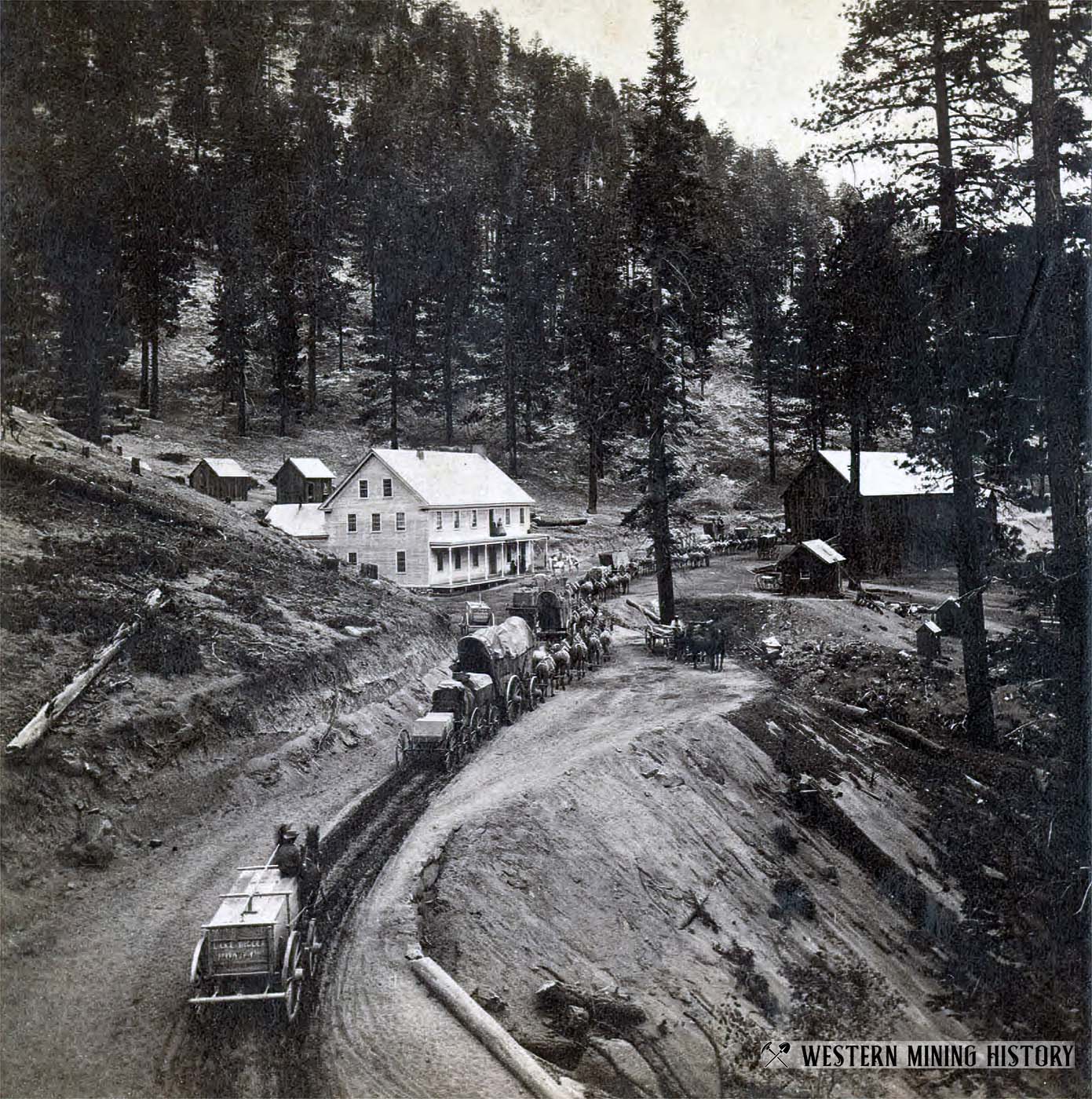

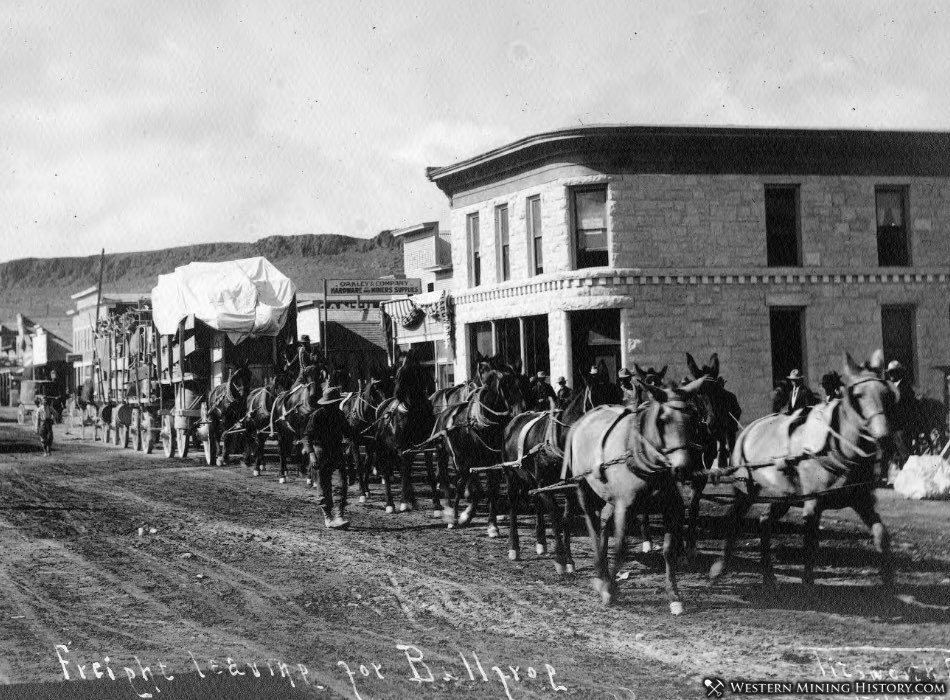

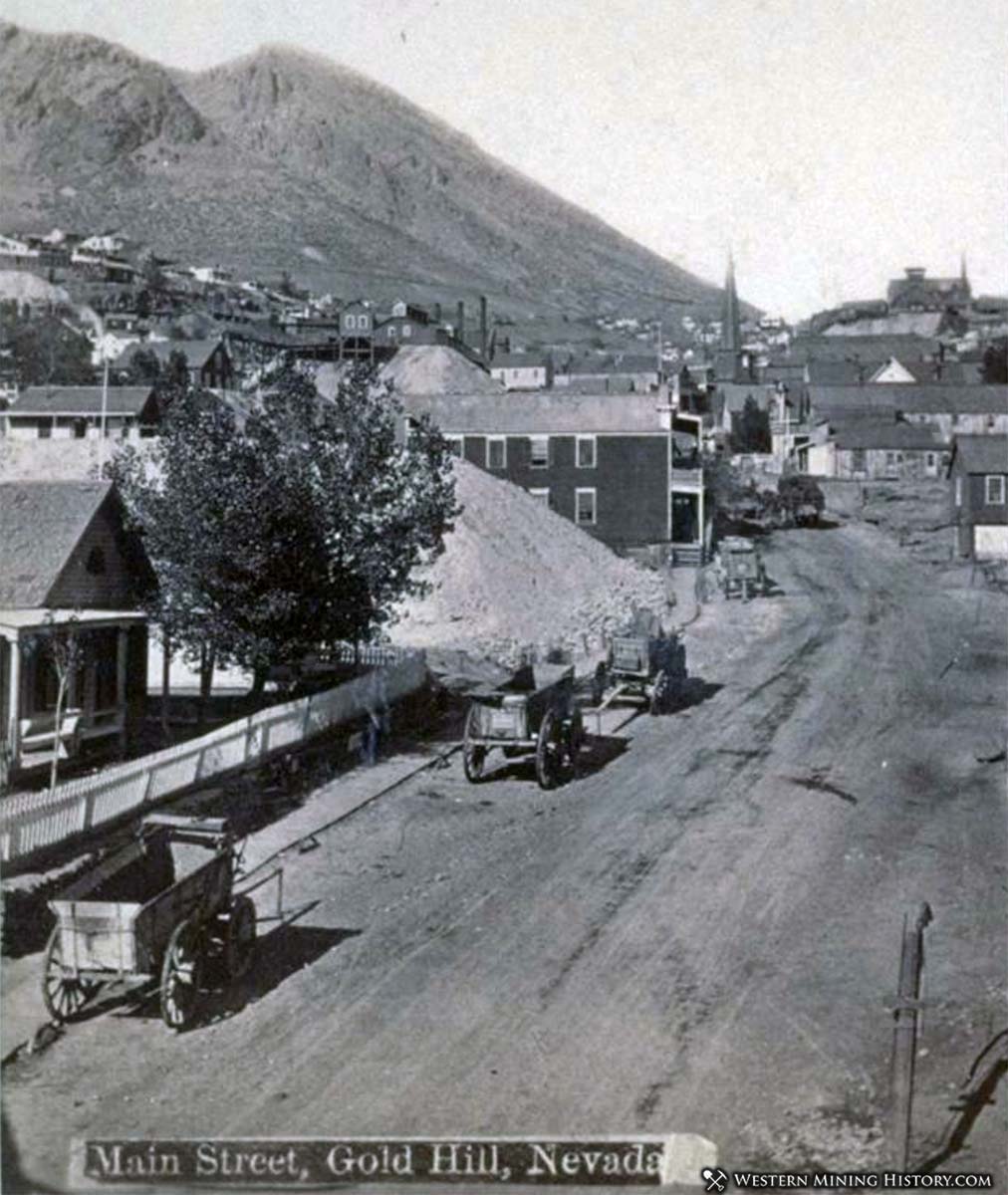

The freighters generally got their loads from the mines, in the form or ore to deliver, from steamboats that carried cargo, from big towns and manufacturers, or from the railroads delivering goods to towns like Denver, San Francisco, or other major stops throughout the West.

It was big business and newspapers were always reporting the arrival of freight – the “West Wind” made our landing last evening, loaded to her guards with a large quantity of freight and two crushers for the mine.

The arrival of a railroad provided not only an impetus for the growth of small towns but new ones often sprang up. There were plenty of spur lines (especially to mining centers) delivering and obtaining materials. The increased need for supplies resulted in fierce competition between freight companies.

Military Contracts were some of the most sought after jobs. Once forts became more numerous, and many were in isolated areas, the army needed to be regularly resupplied. This created a consistent source of work and income and Army contracts often spanned a year.

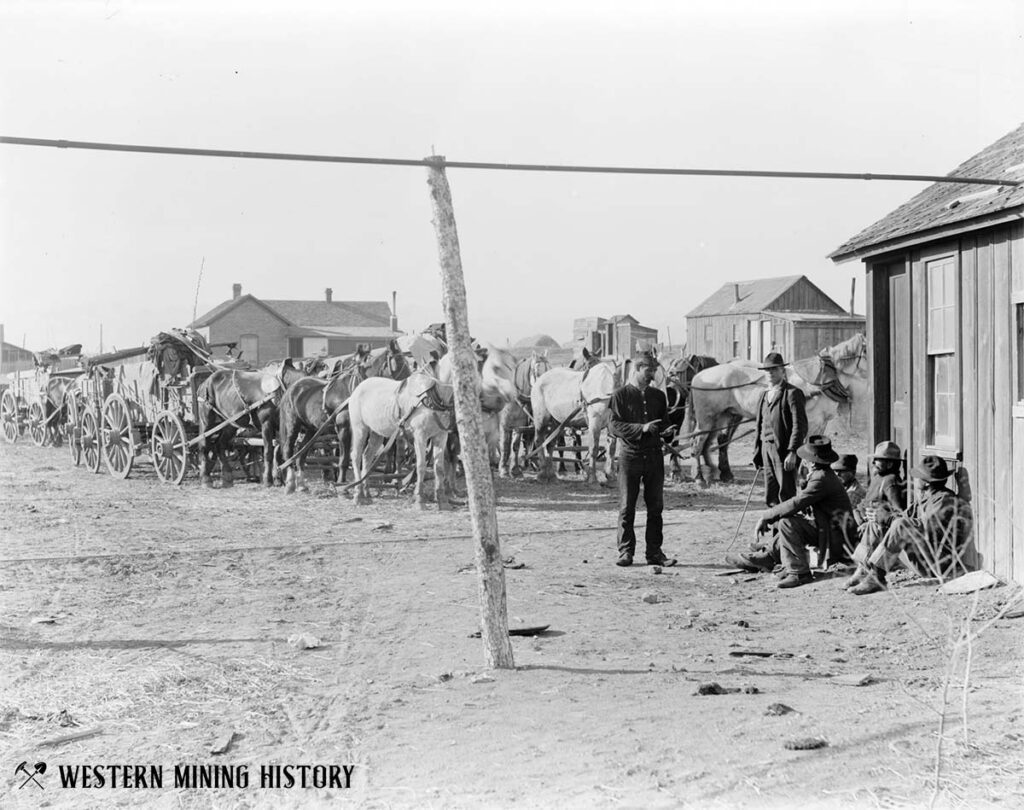

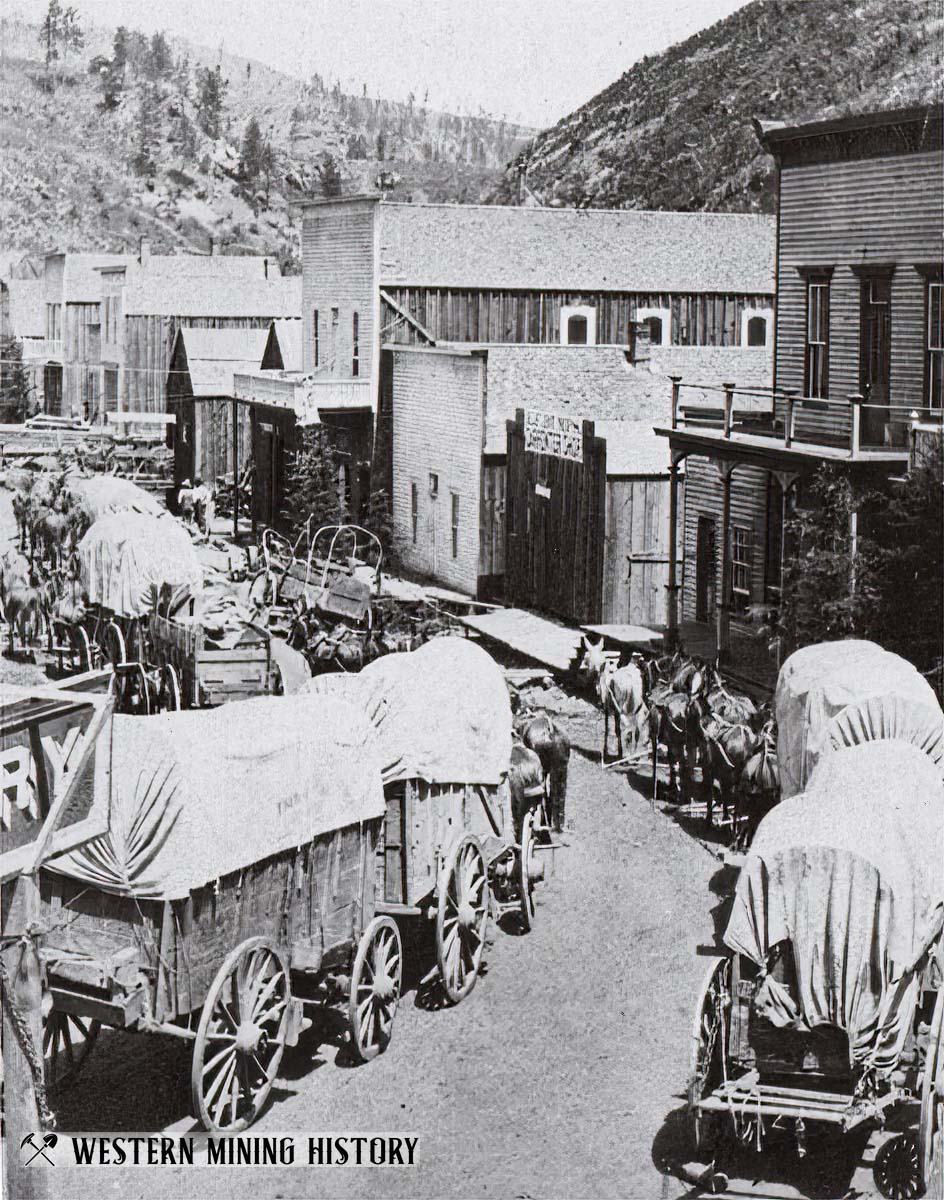

It is hard to envision the number of departures and arrivals of large freight wagons. One paper stated that “the large freight wagons are constantly clogging the streets and last week 110 passed through, each one carrying an average of five thousand pounds.”

Large outfits generally had the larger contracts which called for a string of wagons, a dozen or more in line were not uncommon, this alignment worked best on well traveled roads as a breakdown in one of the front wagons on a rocky or narrow route could cause major problems. Large outfits traveling together provided much more protection and assistance for one another.

Weather might cause delays but was no deterrent when goods were needed or contracts were on the line.

End of The Road

Large freight wagons gradually became victims of progress. Trucks, better and more roads, an increase in rail lines and service to smaller towns lessened the need for many of the big wagons.

As motorized vehicles became less expensive, more reliable, and plentiful, many companies, mining operations, and businesses acquired their own fleet of trucks for delivery. Smaller and more manageable wagons still worked the farms and delivered goods but as the road systems improved and reached more isolated spots, the large freighters became less seen and not needed.

Trucking grew and slowly replaced wagons as the automobile replaced stages and carriages. By 1910 there were still only about ten thousand trucks in the entire country but by World War I and certainly by 1920 the proliferation of paved roads and trucks changed the freight industry.

The speed and service improvements meant the utilization of trucks to carry everything from gasoline to hay, which were more cost effective, quicker, more sanitary, and less cumbersome than using wagons.

Now one can find trucks to fit every need and service –from the giant Belazarus mining truck which can carry 450 tons at once to the small U. S P.S. truck that delivers your mail.

More Freight Wagons

There are many amazing photos of freight wagons at work hidden in various archives. As I run across them, I will add them here, so remember to check back to see how this collection grows over time.

Related Articles

The following articles from Western Mining History explore more on the topics of freighting and transportation in the West.

The Twenty Mule Teams of Death Valley

The Twenty Mule Teams of Death Valley presents text and diagrams from a series of reports by the Historic American Engineering Record. Included are historical images of these iconic western wagon teams.

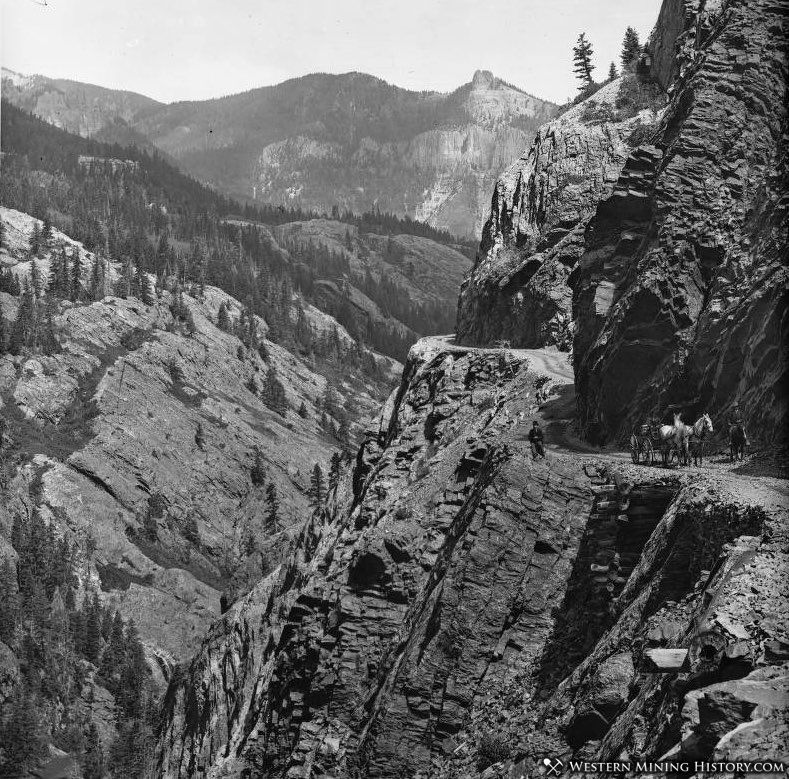

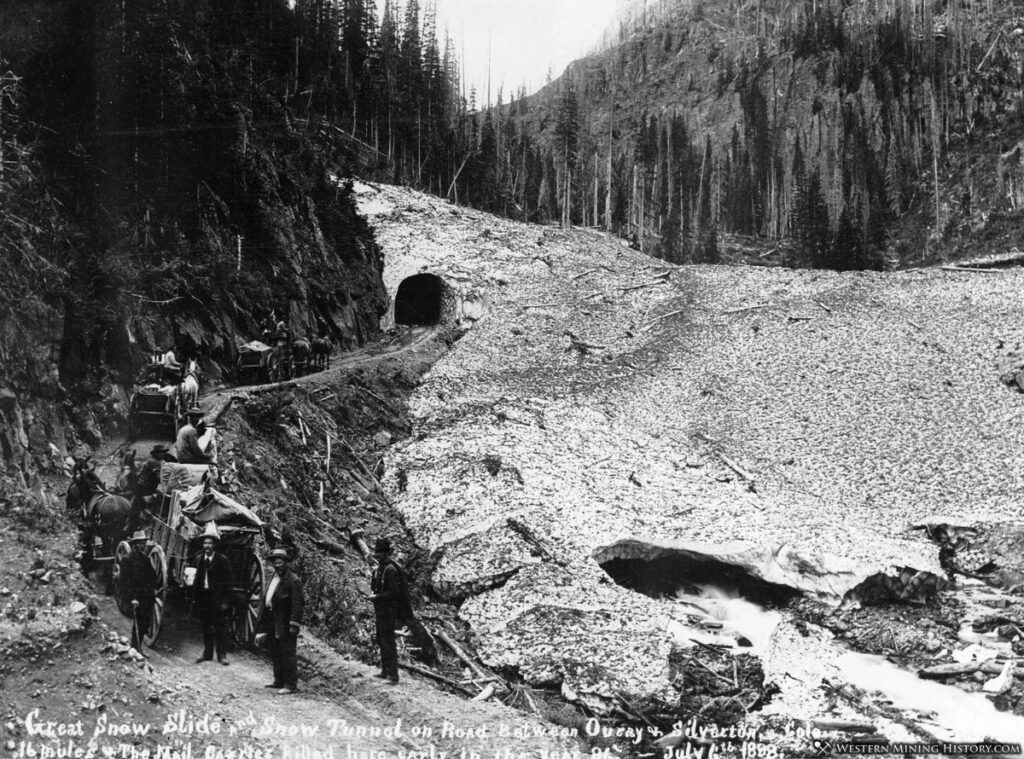

The Impossible Road

For years attempts were made at building a road between Ouray and Silverton, but these attempts were always a failure. Building the road was thought to be impossible by some, but by the mid 1880s Otto Mears, premier road builder of the region, was able to complete the job.

The Impossible Road: Incredible Photos of the Otto Mears Toll Road

Bibliography

GENi-Old West Teamsters and Freighters

History Net-“Though Bullwhackers often swore-etc”.-John Koster

HistoryTrailsWest.com—“Our Wagons”

Legends of America-Russell, Majors and Waddell

mulemuseum.org-Mule Teams and Freight Wagons

ouraynews.com—From Wagons to Apples-etc.,June 17,2020

Overland Freighting in the Platte Valley-1937-U. of NebraskaFloyd Bresee

The Story Behind Ketchum’s Famous Ore Wagons

Wagons on the Santa Fe Trail-Nat. Park Service-1997-Mark L. Gardner

Wheels that Won the West.com

National Parks Service – Twenty Mule Teams