Text By Gary Carter. Photos sourced by Western Mining History from various archives.

Author’s note: this is a short synopsis of early stagecoach activity in the far west. Please note that different sources may provide slightly varying numbers when describing coaches, men, way stations and animals used. The readers are directed to the bibliography for further reading and more in-depth information.

By 1917 over half a million Ford Model T’s were on the road, and rail service had reached many of the smaller towns in the West. But it was really the coming of the motor bus that finished off the stagecoach.

In Arizona, which was not a state until 1912, stagecoaches were still carrying passengers to remote areas and small towns as late as 1917! In tiny spots not receiving coach service, the buckboard was the conveyance to get potential passengers to the nearest stage station or stop.

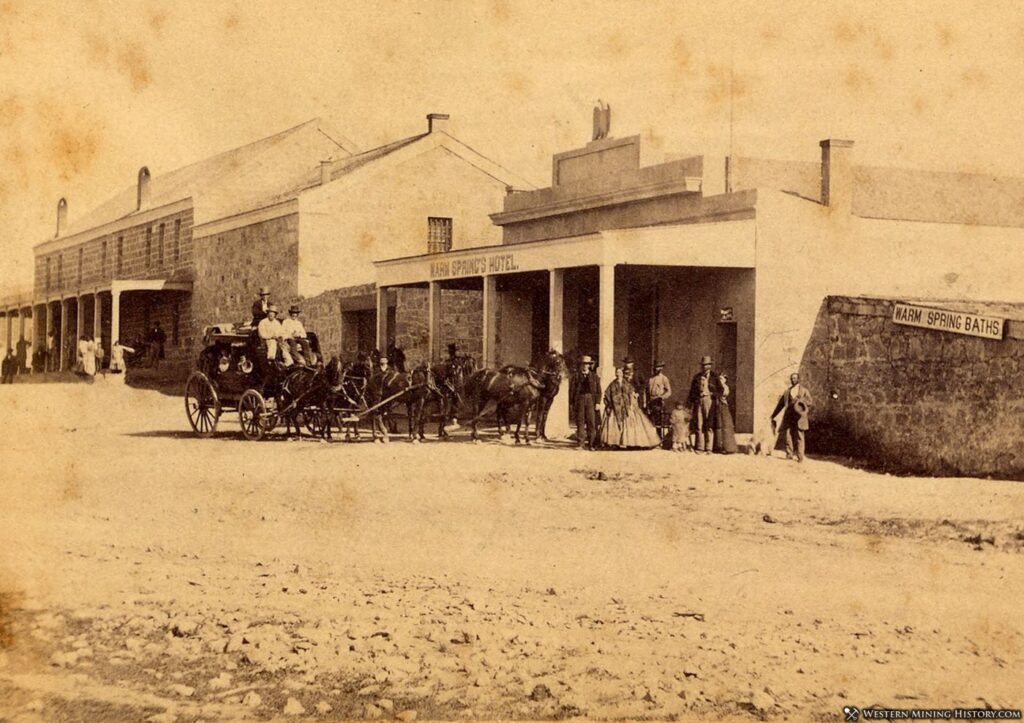

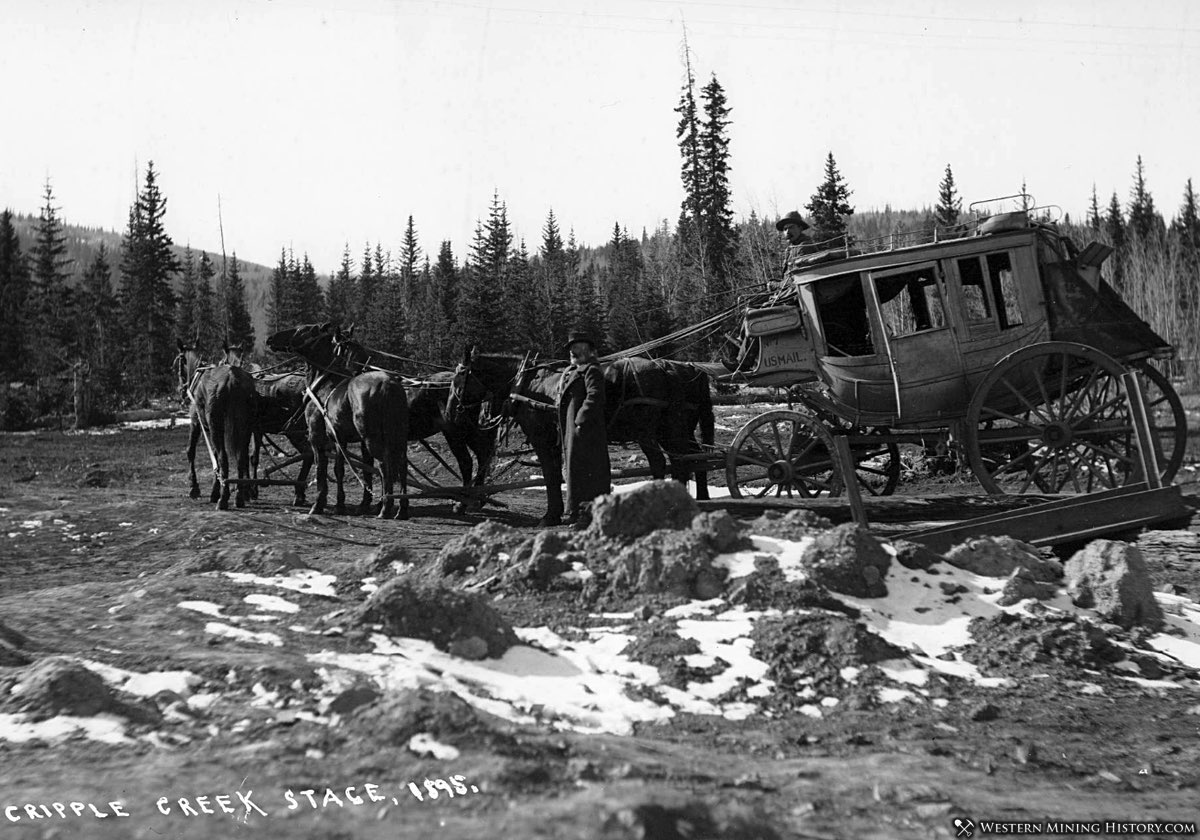

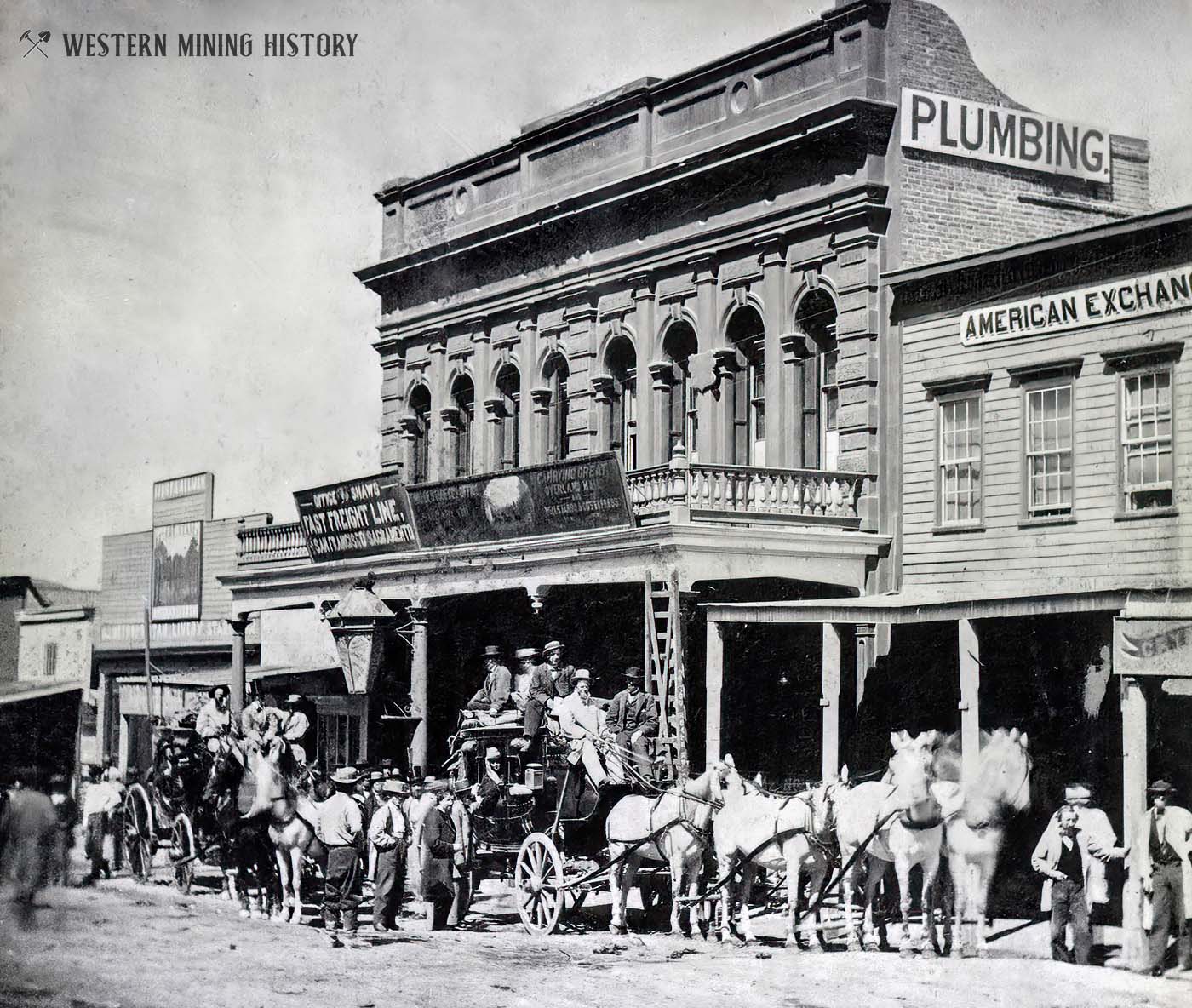

While stages were prevalent as early as the late 1700s in the East, it was not until the 1850’s that they became more common in the mining states of the West. The California Gold Rush and subsequent mining excitements in other western states meant increased population and the need for a vehicle to carry passengers, mail, bullion, and baggage. Shortly before and after the Civil War the military established a multitude of forts which needed mail and passenger access.

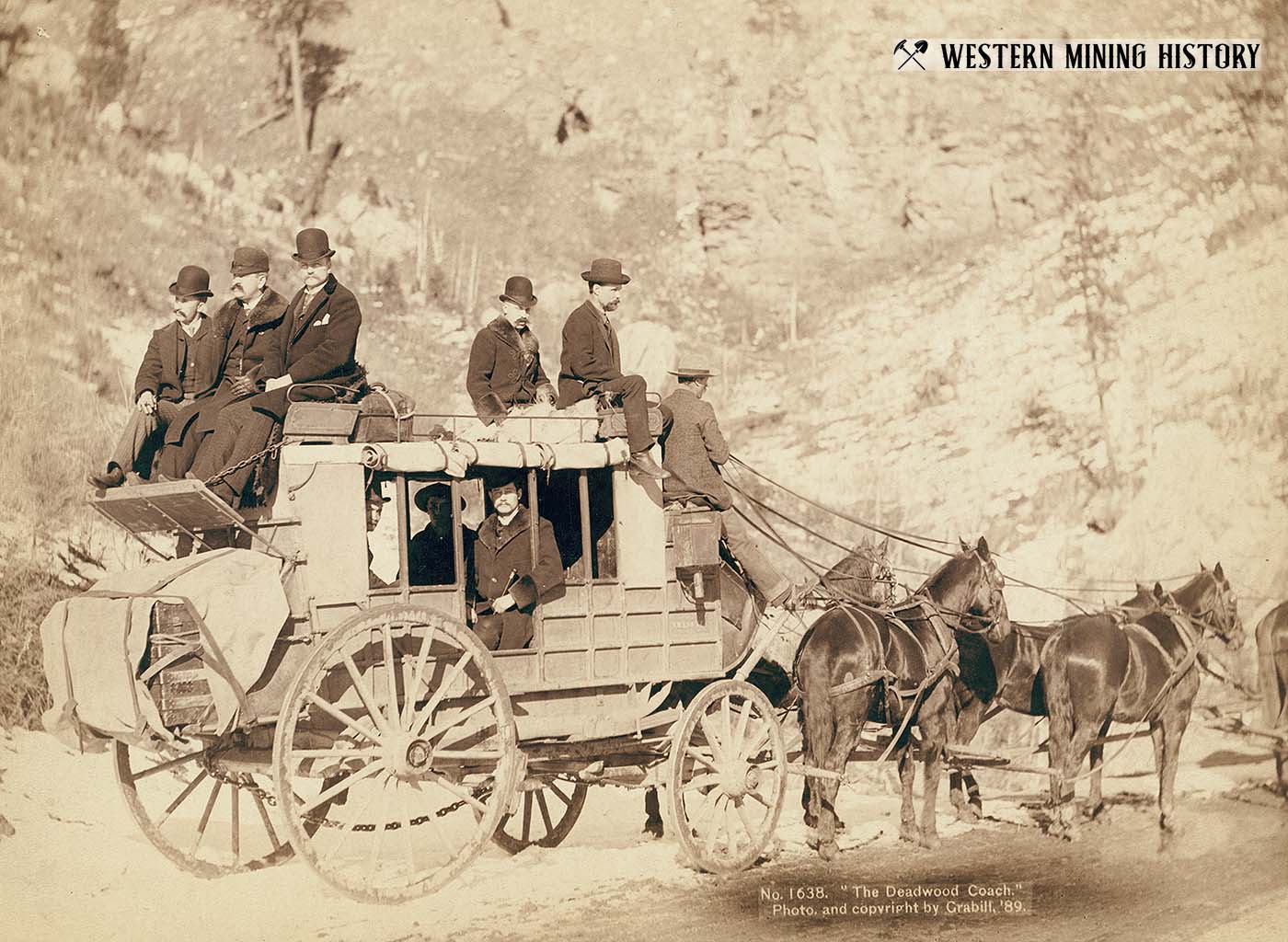

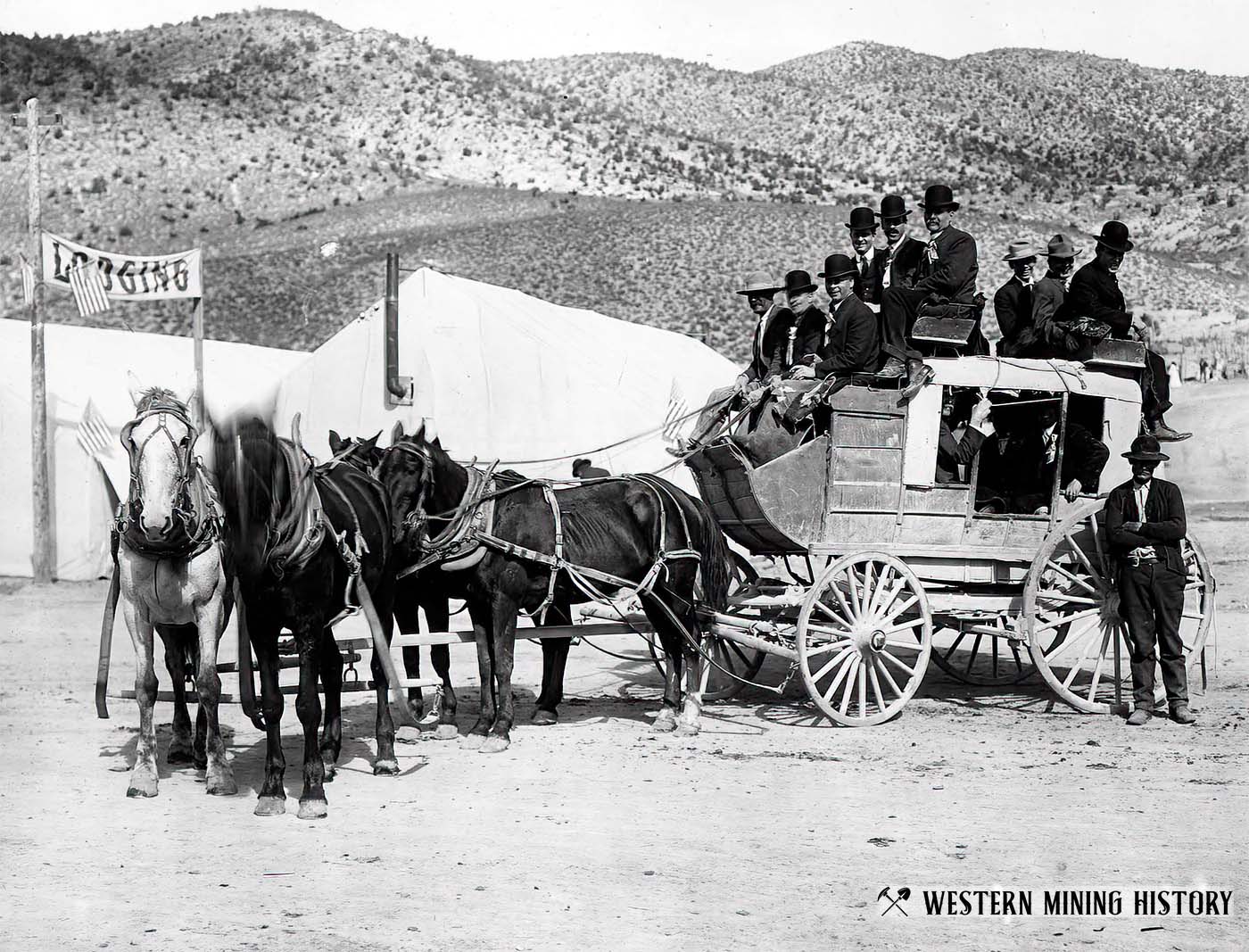

The one ton Concord coach and the smaller, lighter Celerity coach could seat nine (front, middle and back rows each sat three) and were the preferred makes. The three rows made it necessary for those seated in front and in the middle row to often interlock legs.

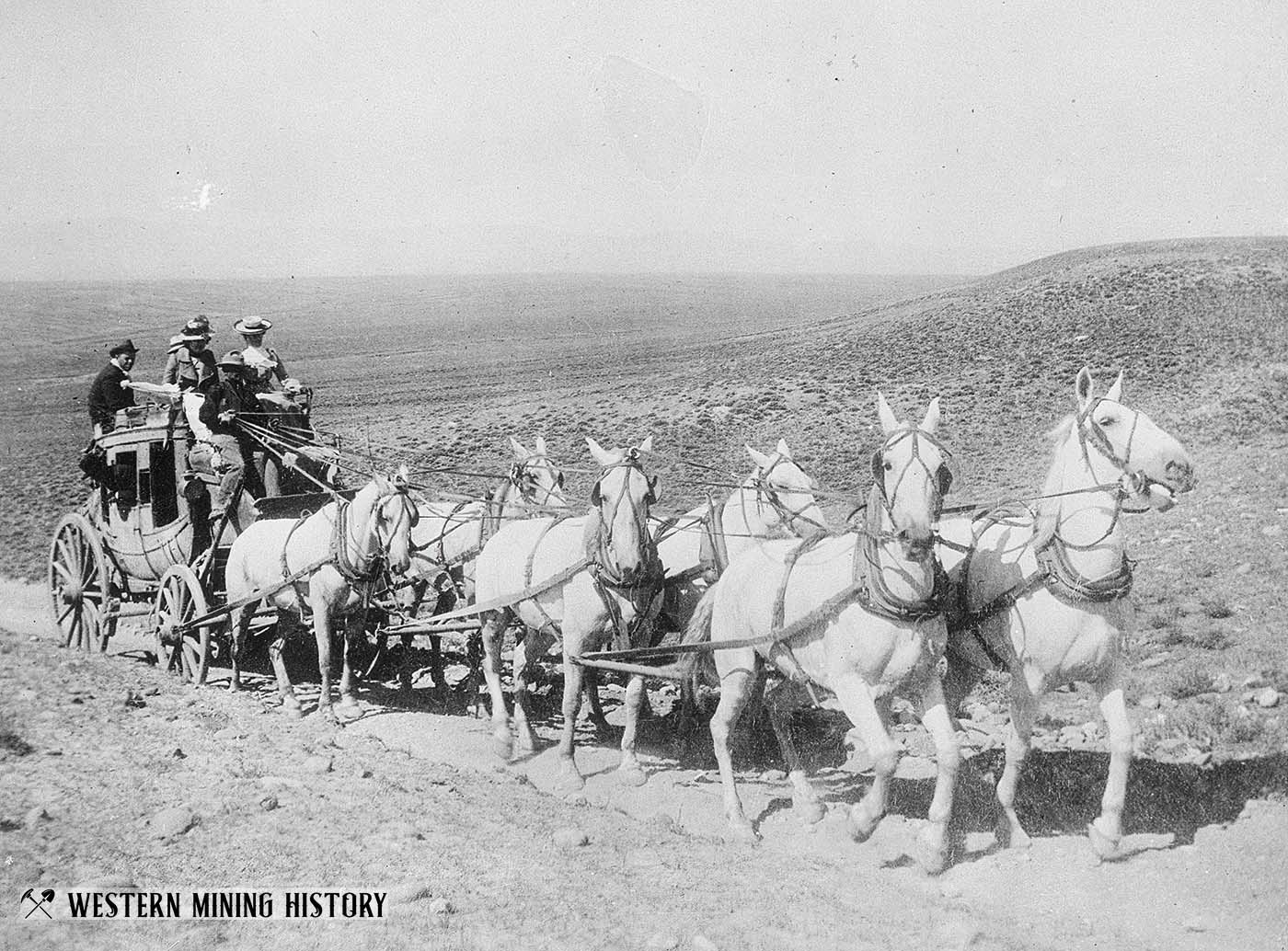

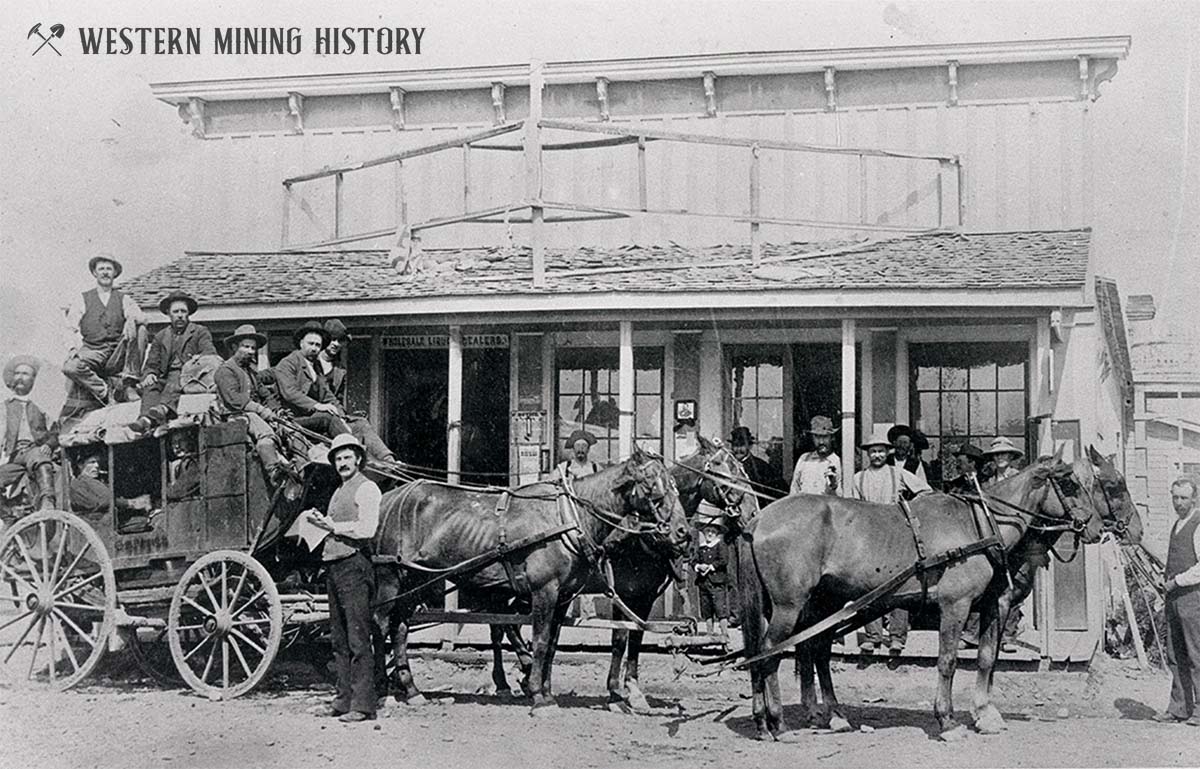

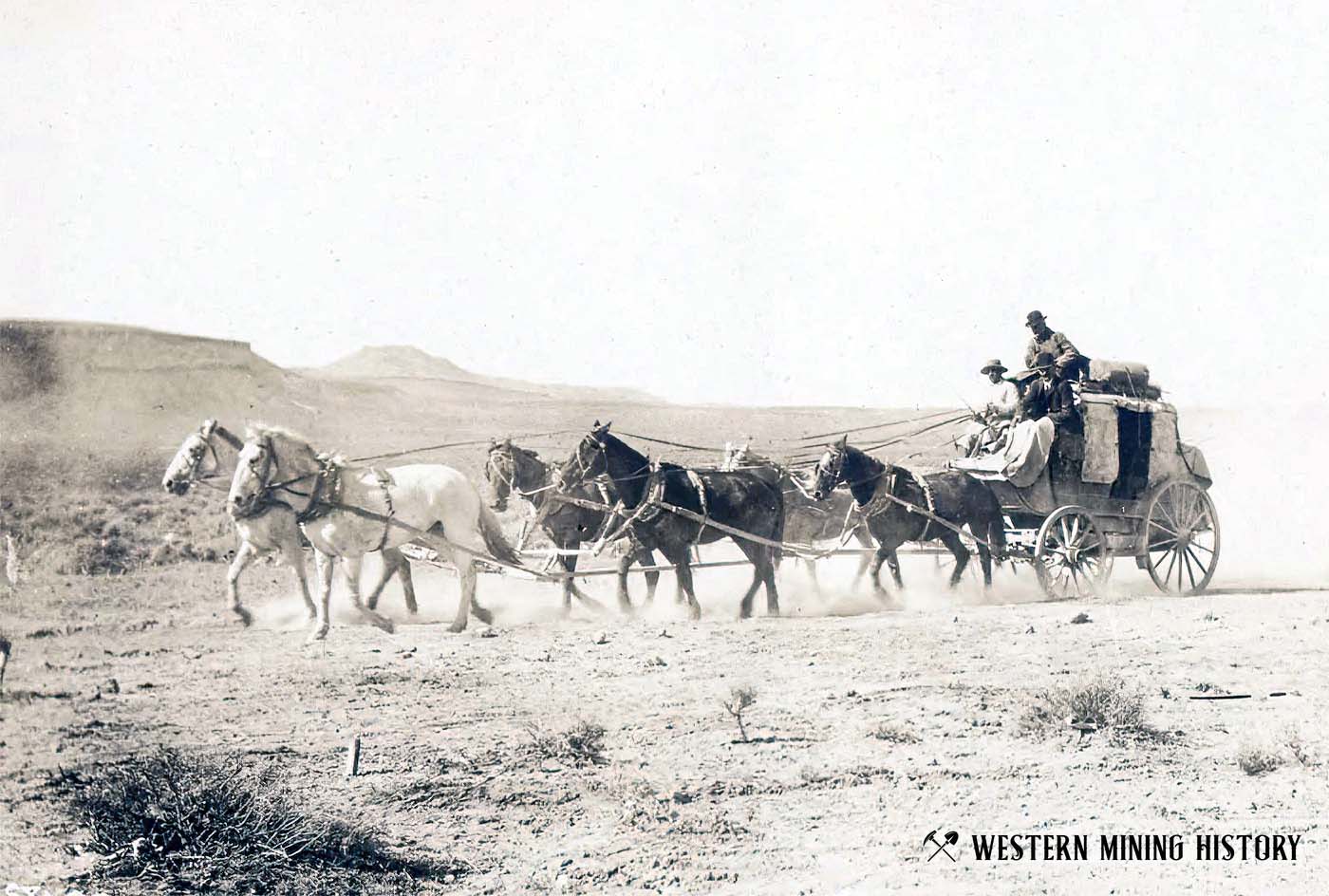

The ride was dusty, uncomfortable, hot in the summer, cold in the winter, windy and wet when it rained. The smell of four-six horses, unkempt passengers, cramped seating, fear of breakdowns, hostiles and robberies added to the anxiety.

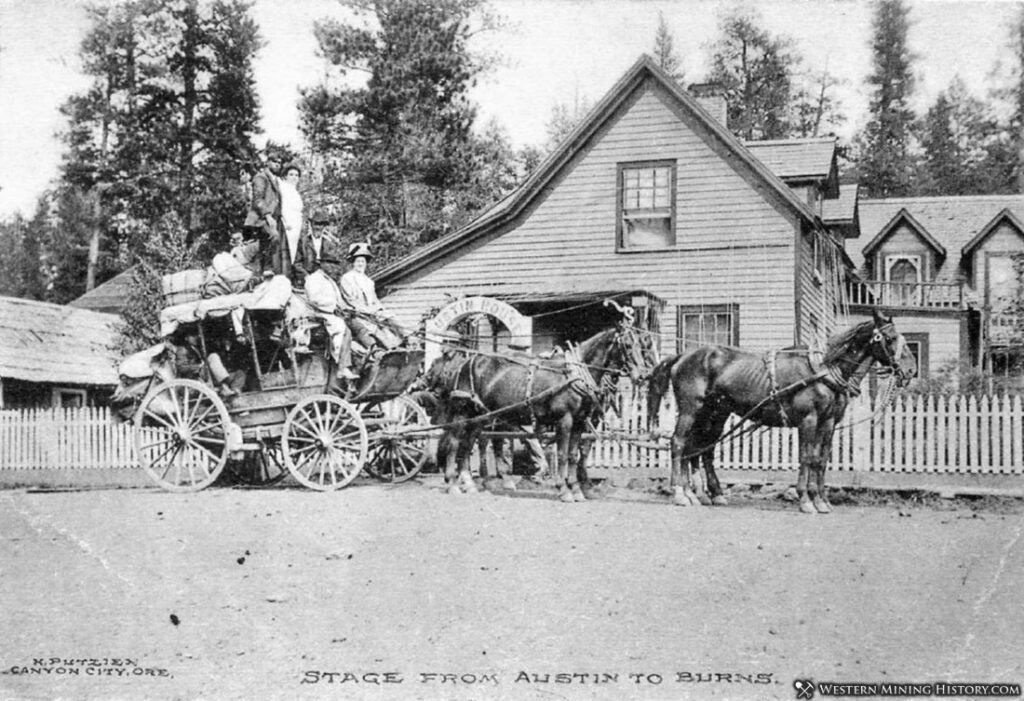

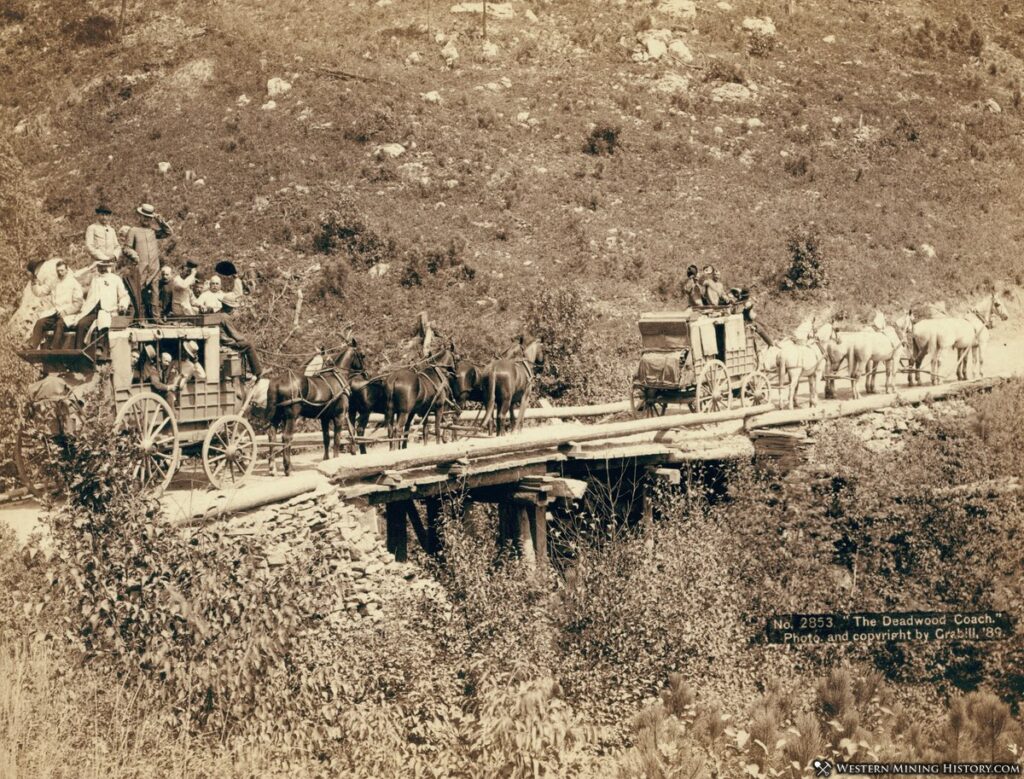

Each of the passengers could bring up to 25 pounds of luggage, which were loaded into a leather pouch (aka boot) at the rear. If there was room, for a cheaper fare, and on short runs some folks took their chances on the top of the stage.

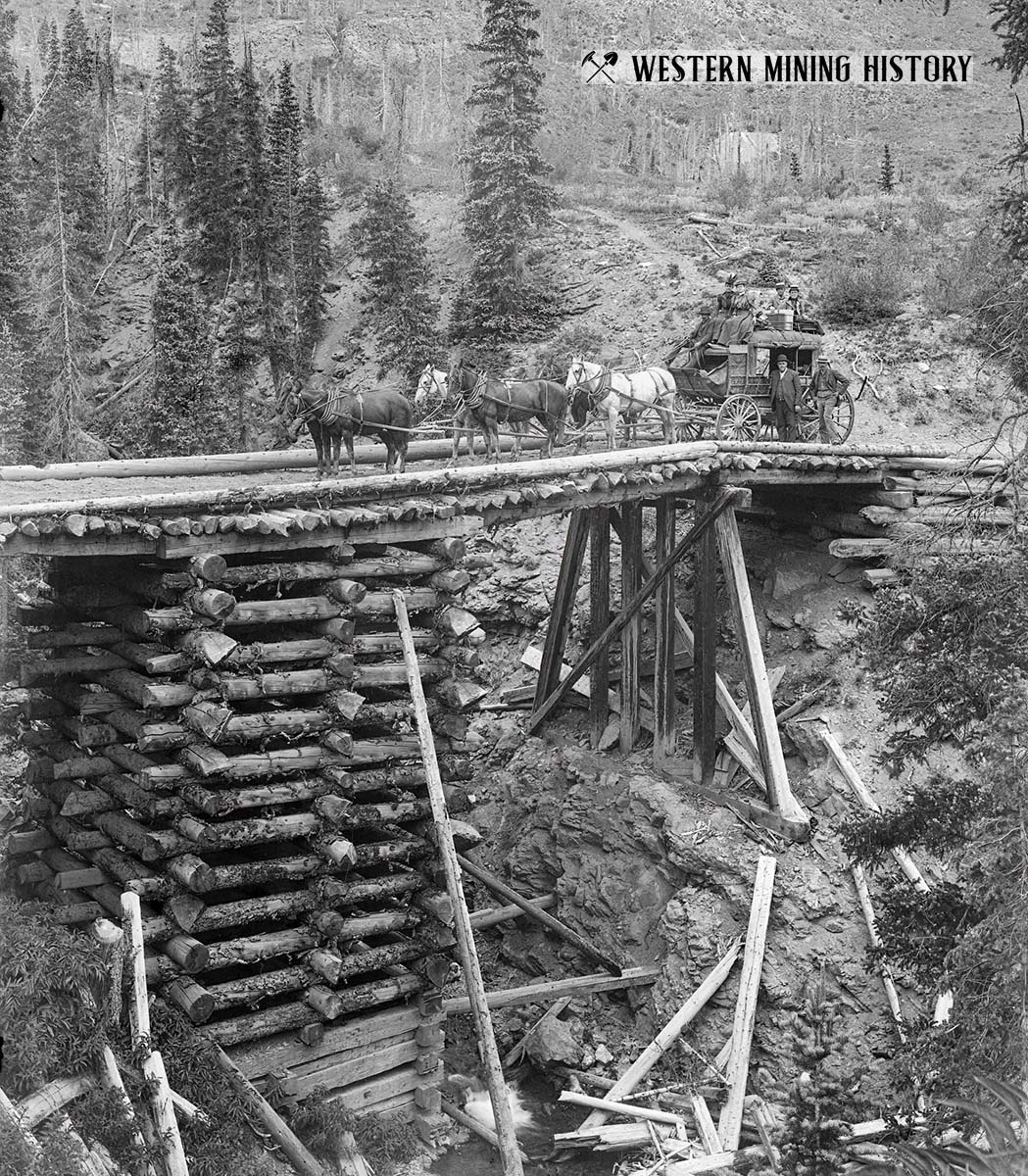

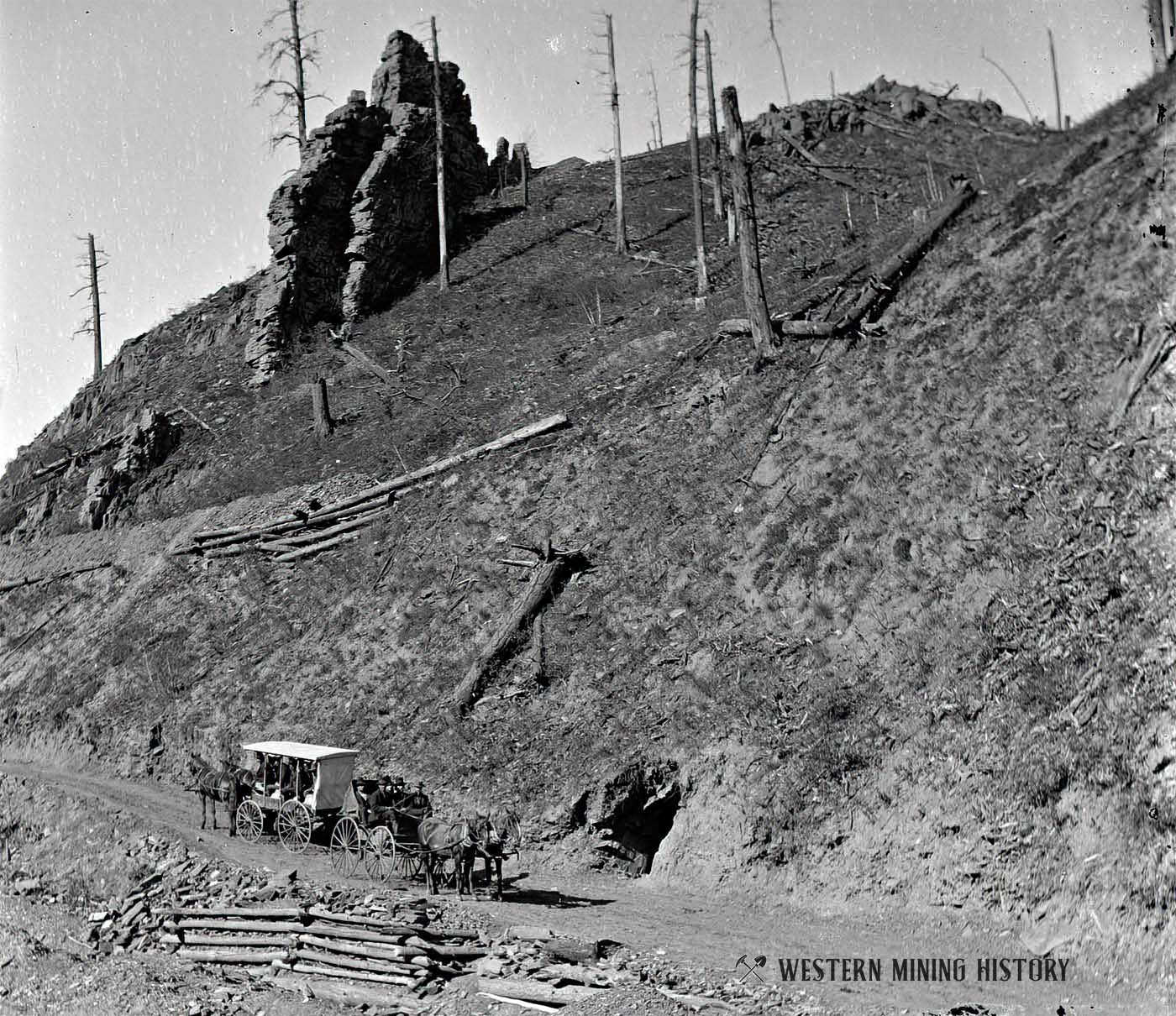

The “roads” (a misnomer) generally followed the most easily accessed natural contours with a few rocks pushed out of the way here and there. The high banks at stream crossings were knocked down just enough so the coach could slip rather than fall down into the stream. Eventually the continual travel, especially of big freight wagons carrying ore, helped to somewhat smooth down the trail.

It was not uncommon for passengers to assist in pushing or exiting to reduce weight to get the coach over especially difficult spots. Many of the current paved highways and Interstates in Arizona and other western states follow or parallel what was an old stage road.

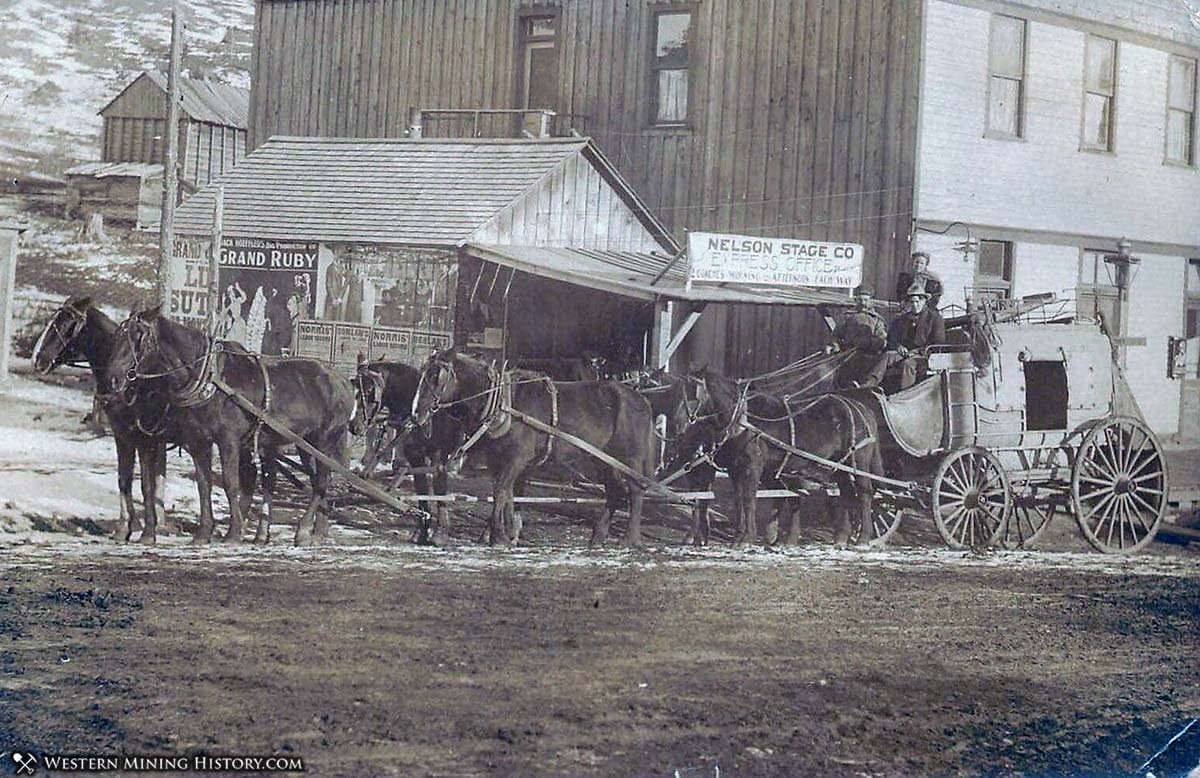

Western movies showing stages running full out into town were theater, as horses and mules were generally worked at a pace of four to five miles an hour less they tire. A driver and helper, often with a shot gun, handled a team of four to six animals. The animals were generally changed out at each stage stop, which was from 10 to 15 miles apart. Later, long runs of 40 miles necessitated carrying water and feed for the horses.

A common stage run in Arizona was from Phoenix to Prescott, often called the Black Canyon Line, a distance of 100 miles, at a one way cost of about $10. Since stops at small mining towns and animal changes were needed, a one way trip generally took longer than a day. The Black Canyon Line, depending on the day, made stops at Aqua Fria, New River, Swillings Place, Black Canyon, Tip Top, Gillette, Bumble Bee, Cordes, Camp Verde, Mayer, Dewey, Prescott, and Fort Whipple.

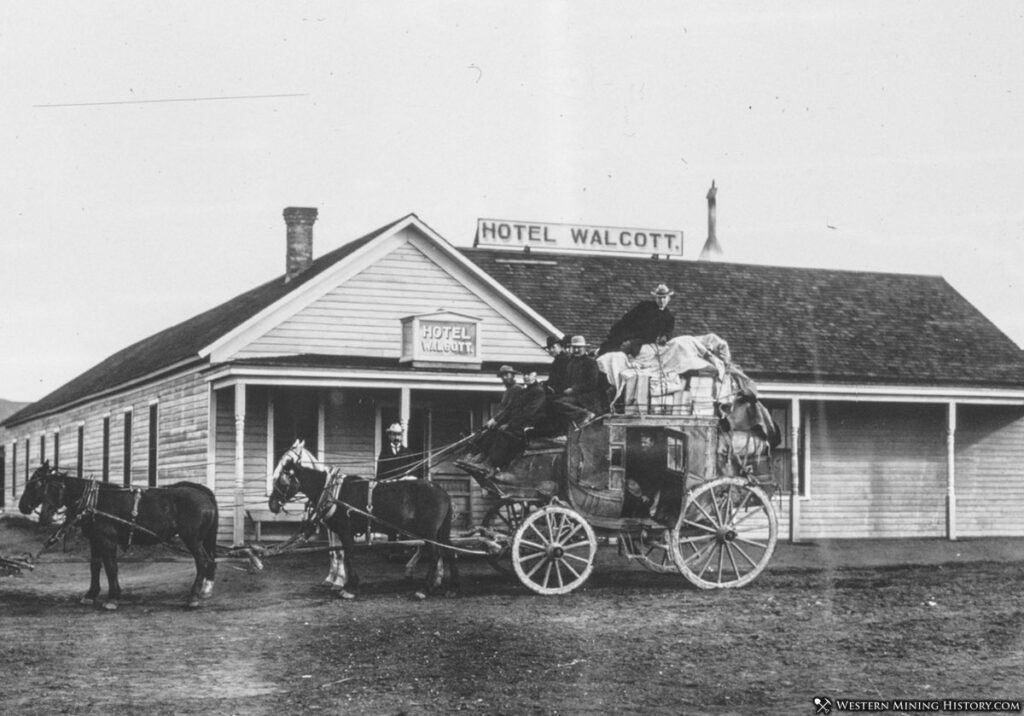

Stage schedules were quickly committed to memory as once a day or a few times a week were often the only times the stage went “up or down” the route. Stagecoaches, and the stations that serviced them, were vital links between remote mining camps, and part of the social fabric of the frontier West. Although stage stations helped keep the lines running, passengers often slept sitting up in the coach as most stations had neither the space, help or food to house a full coach of passengers.

Robberies were not quite as numerous as the western pictures depicted but the Black Canyon line averaged slightly more than one a year from 1879 until 1895. Wells Fargo, due to robberies, stopped express deliveries of bullion from the famous Vulture Mine, in Arizona, after 1884.

It should be noted that Wells Fargo, a key stage line in the west, did not own stages in Arizona since they had entered Arizona late and independents were already established. The company did contract with stage lines to make express and bullion deliveries and ran its company owned coaches in most other states.

From the 1860s until the late 1800s, stagecoach lines proliferated, but many companies only lasted a short time. Expenses were high and many small, independent outfits competed for business, but unless a government mail contract could be obtained many of the lines went broke. The coach cost well over $1500, and repairs, horses, feed, drivers, and stage stop upkeep combined to make for high overhead.

The Overland Mail Stage Route

So far the discussion has centered on independent stage lines linking small towns and mining camps, often in the same state. Through the 1840s an 50s mail, not passengers, was carried from east to west by private companies. As western territories continued to grow through the 1850s and 1860s, more travelers headed west and mail carriers started catering to passengers.

The government offered an unheard of six year, $600,000 contract to carry mail with the stipulation that service should be twice a week in each direction and each trip was to be done in 25 days or less to carry mail from St. Louis, Missouri to San Francisco, California.

Enter John Butterfield, of Utica, New York, owner of numerous stage lines in the state. After winning the contract, he invested around $1 million in building the new line and route which was sometimes known as the called The Butterfield Line, or The Overland Mail.

The coaches were also allowed to carry passengers who paid $200 to ride the one way–2,000 plus miles. Much of the route, to avoid bad weather in the winter, crossed southern Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and then entering southern California and turning North, traveling near much of what is now Highway 99 and over to San Francisco.

It took over 4 days and 27 stage stops just to cross Southern Arizona. A total of around 200 manned relay stations were established, over 1500 animals plus feed, 800 or so workers and 250 coaches were acquired to support the endeavor. It was no wonder that a large government contract was needed.

The stage coaches for the long overland trip were often Celerity coaches which were much lighter, had less suspension, and were more open to the elements than the Concord coaches. Perhaps their key feature, for Butterfield, was that the Celerity was much less expensive than the Concord.

Passengers had no way to keep clean, or comfortable. Stops were quick and often to change horses without meals. If a station did serve food it was quite fast and unappetizing. Travel at night was accomplished by moonlight and at other times by driver judgement and memory.

Up until the late 1880s the overland trip, because of Apaches, was much more dangerous through West Texas, Southern New Mexico and Arizona than other stretches. Butterfield robberies were almost non existent however, as the area traveled was so remote that the company rule was not to transport bullion or precious cargoes.

During the Civil War the government eventually forced the southern Butterfield route, because of Confederate hostilities, to be abandoned, and in April of 1861 a new more northern route called The Central Overland Trail was used. It went from Salt Lake City to Ft. Churchill, Nevada (near present day Silver Springs off 95 alt.). Travelers used it and the old emigrant trail to California until the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869, which became the preferred mode of cross country travel.

Local stages still made short runs until the automobile and motor buses became popular and reliable. In remote areas the stagecoach was still a transportation option until the late 1910s, but ultimately the automobile prevailed and the age of the stagecoach came to a close.

Related: Stagecoach Photos From Mining-Era Colorado

Bibliography:

Hanchett, Jr. Leland J., Catch the Stage to Phoenix, 1998

Hollon, W. Eugene, Great Days of the Overland Stage, June ,1957, Vol. 8, Issue #4

Ormsby, Waterman L., The Butterfield Overland Mail-etc., Univ.of Cal. Press, 1991

Ring, Bob, Arizona Daily Star, Rings Reflections, 06/28/2012

Rozam, Fred, A., Establishing Transportation on the Black Canyon Route , see Buckboards and Stagecoaches, 1989

Some information was obtained by the author on trips to historic sites in 2012