In October 1849, a group of twenty wagons heading for the recently discovered California gold fields left a wagon train near the Utah-Nevada border. They planned to take a shortcut along an old Spanish trail and desert cutoff.

Conscious of what had happened a year earlier to the Donner Party, whose members had been trapped in the mountains by winter and lost nearly half their number, these 49ers were anxious to cross the Sierra Nevada before snow blocked the passes.

Instead, they wandered there lost and half-starved for four months.

When they finally trudged out of the desert, one of them bid it farewell saying “Goodbye, Death Valley.”

It was a name that stuck.

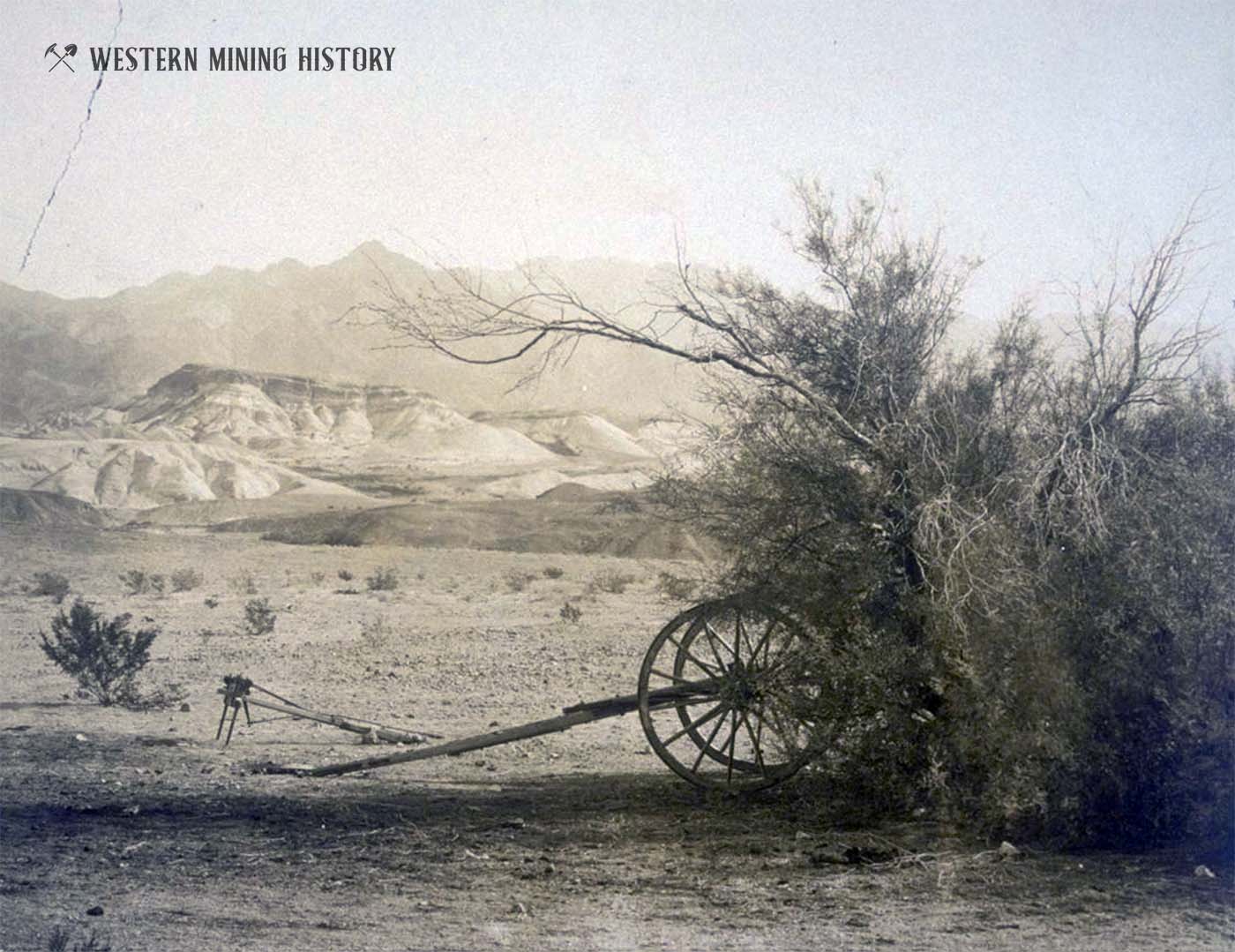

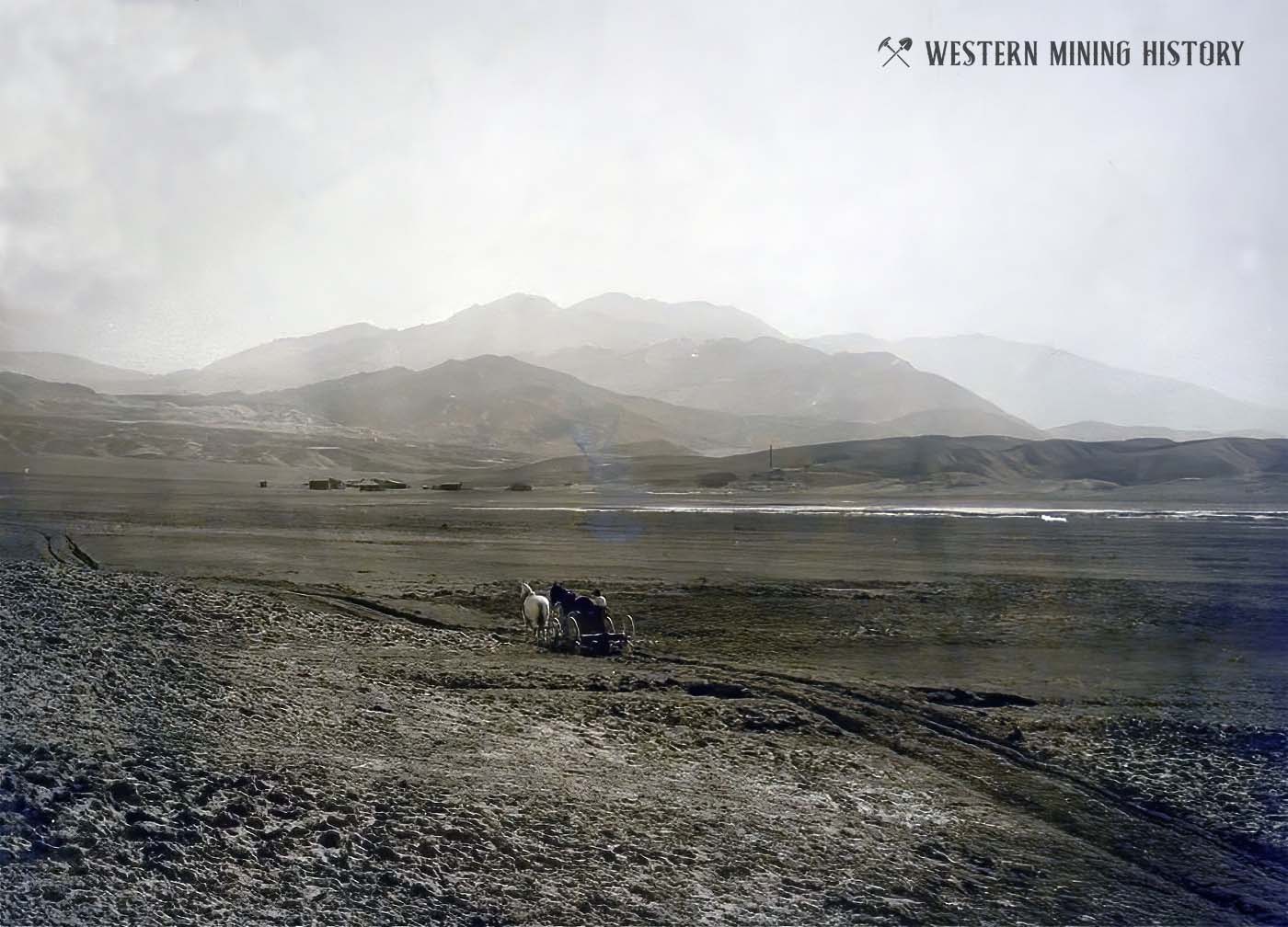

Though these gold-seekers had found a small amount of silver in their crossing, the hot, dry, and inhospitable area seemed forlorn, empty, and useless. Death Valley is as much as 282 feet below sea level, the lowest spot in the Western Hemisphere; temperatures there have been recorded as high as 134 degrees F and yearly rainfall is less than 2.5 inches. It seemed a wasteland.

Nonetheless, years later prospector Aaron Winters was residing there near Furnace Mountain with his wife Rosie near in a hovel described as “close against a hill, one side half-hewn out of rock with a thatched roof” when he encountered a man named Harry Spiller who told him about the mining of white crystals taking place in nearby Nevada.

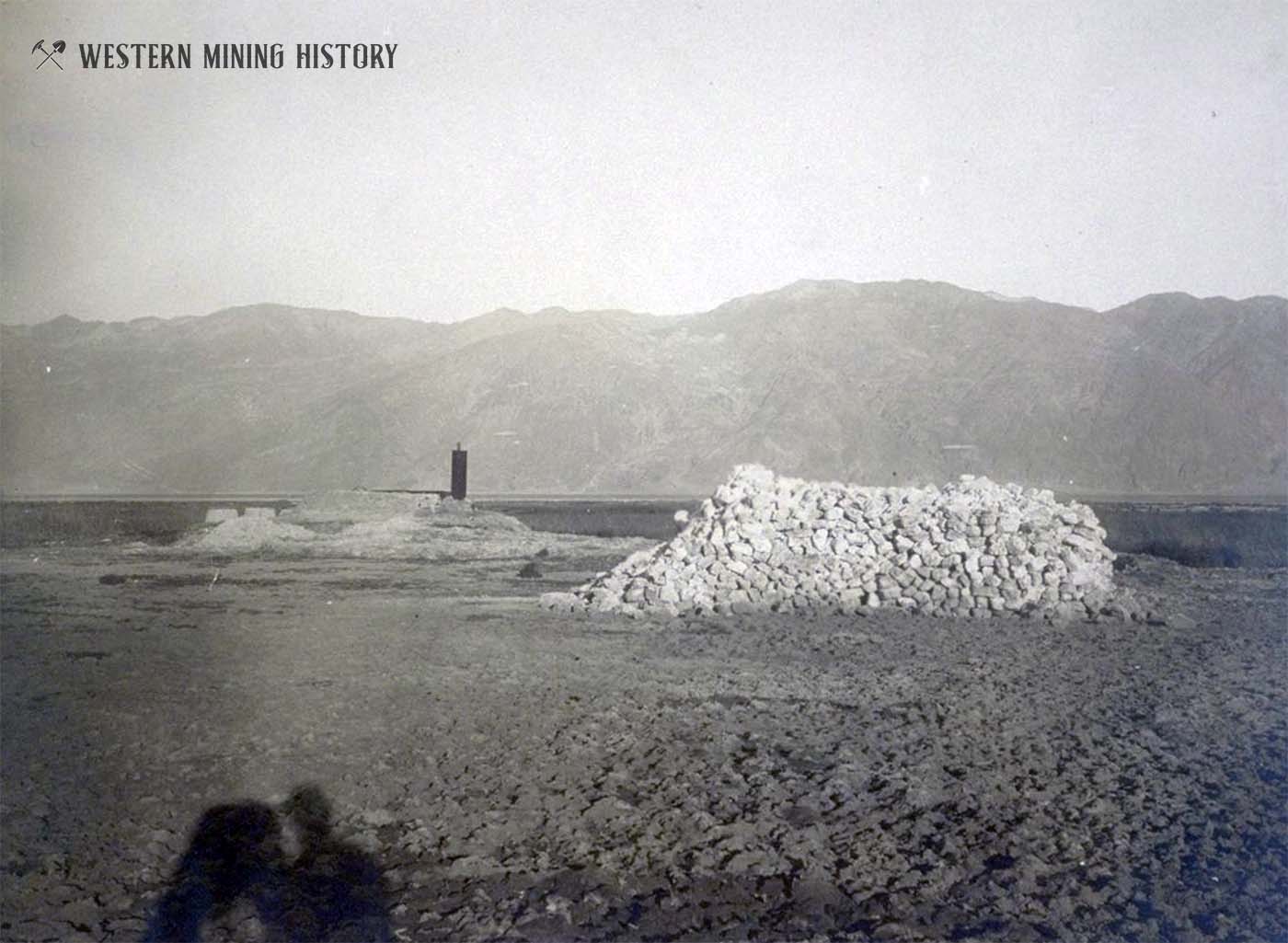

Winters thought he had seen such crystals—they looked like cotton balls—at a marsh near Furnace Creek. He harvested some of the crystals and had them analyzed – they were borax.

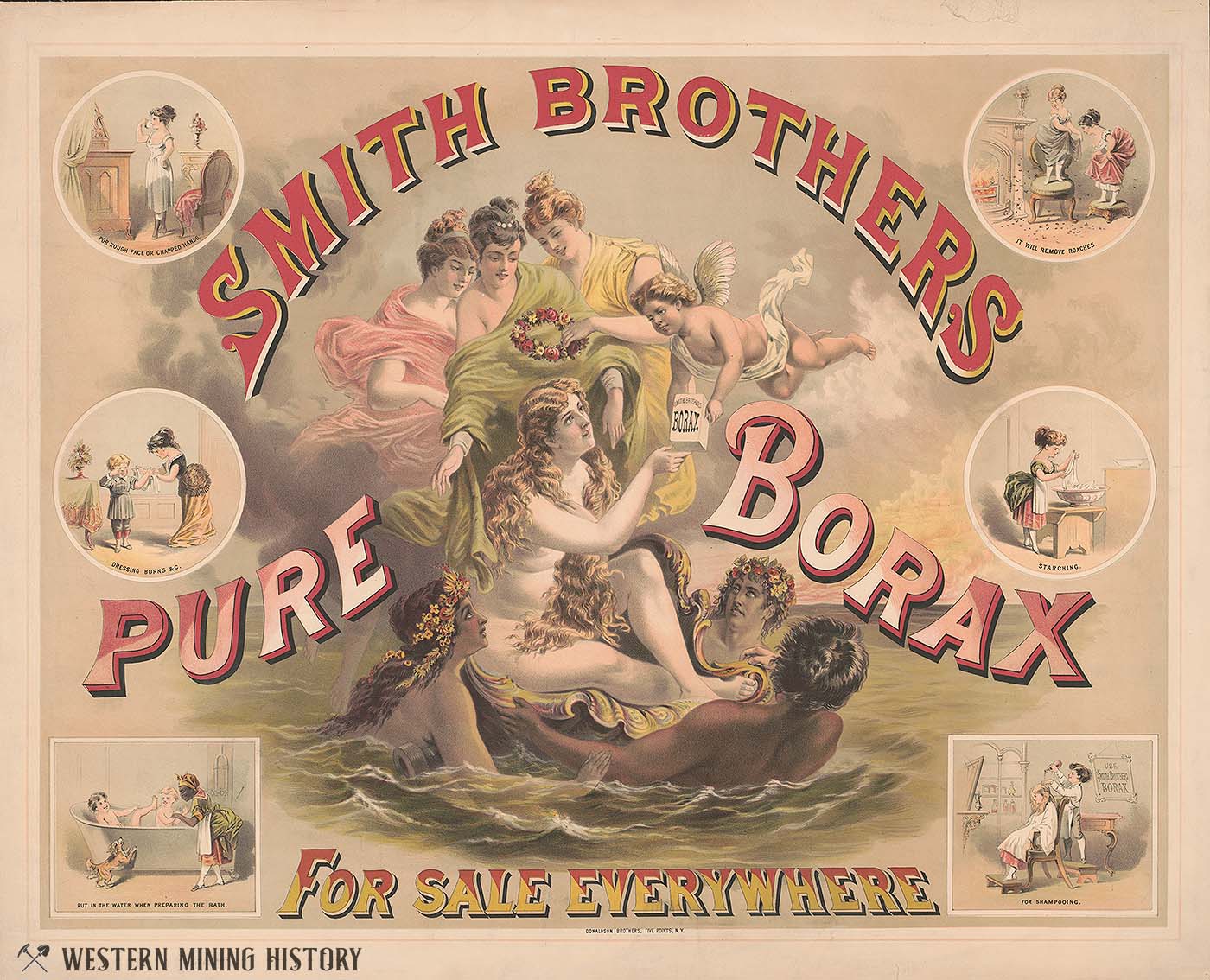

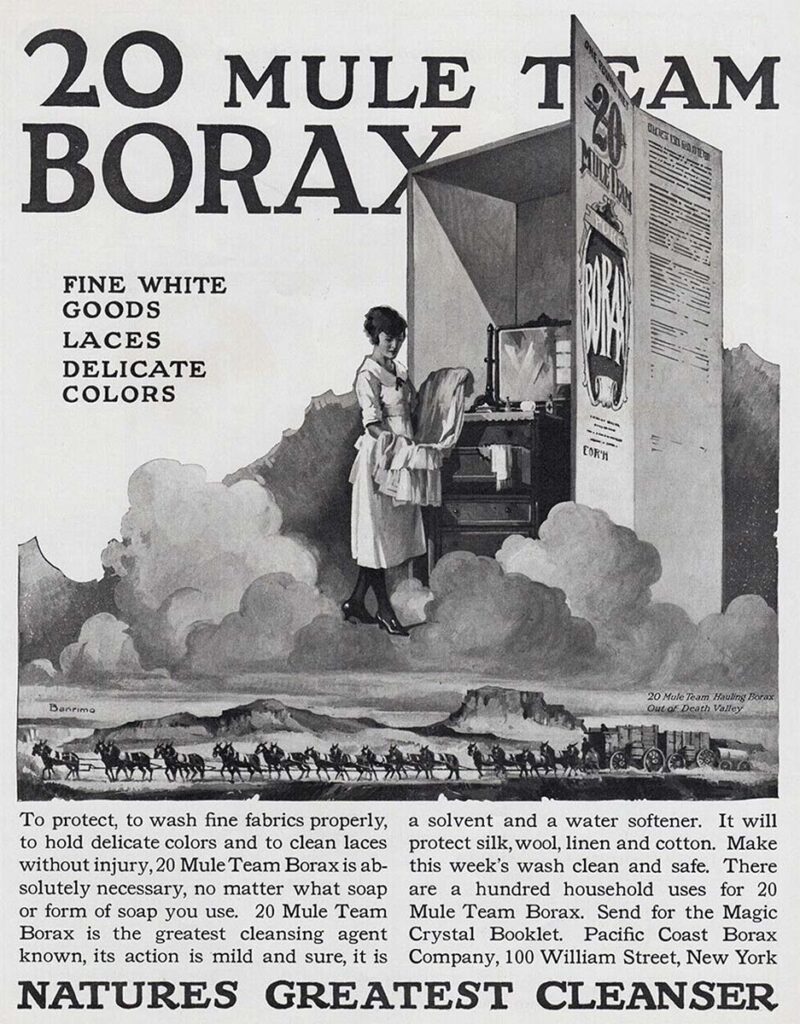

Known chemically as sodium tetraborate or disodium tetraborate, borax is a combination of the elements boron, sodium, and oxygen and has been prized for centuries as a cleaning agent. (Marco Polo is said to have brought some back to Venice from his Asian travels in 1295 BCE).

It is used as a cleaning agent and supplement to detergent, in the manufacture of the herbicide boric acid, in toothpaste, mouthwash, and skin care products. It is also used in making paint and glazes, including the “slime” children love to play with, and has been investigated for possible medical applications.

Millions of years ago volcanic activity and floods raged across the area, and large amounts of mud washed into lakes there forming siltstone beds that were topped with volcanic ash that had drifted over the lakes and settled. That ash contained boron, and as water evaporated from the lakes it left crystalized boron deposits.

Harmony Borax and the Twenty-Mule Teams

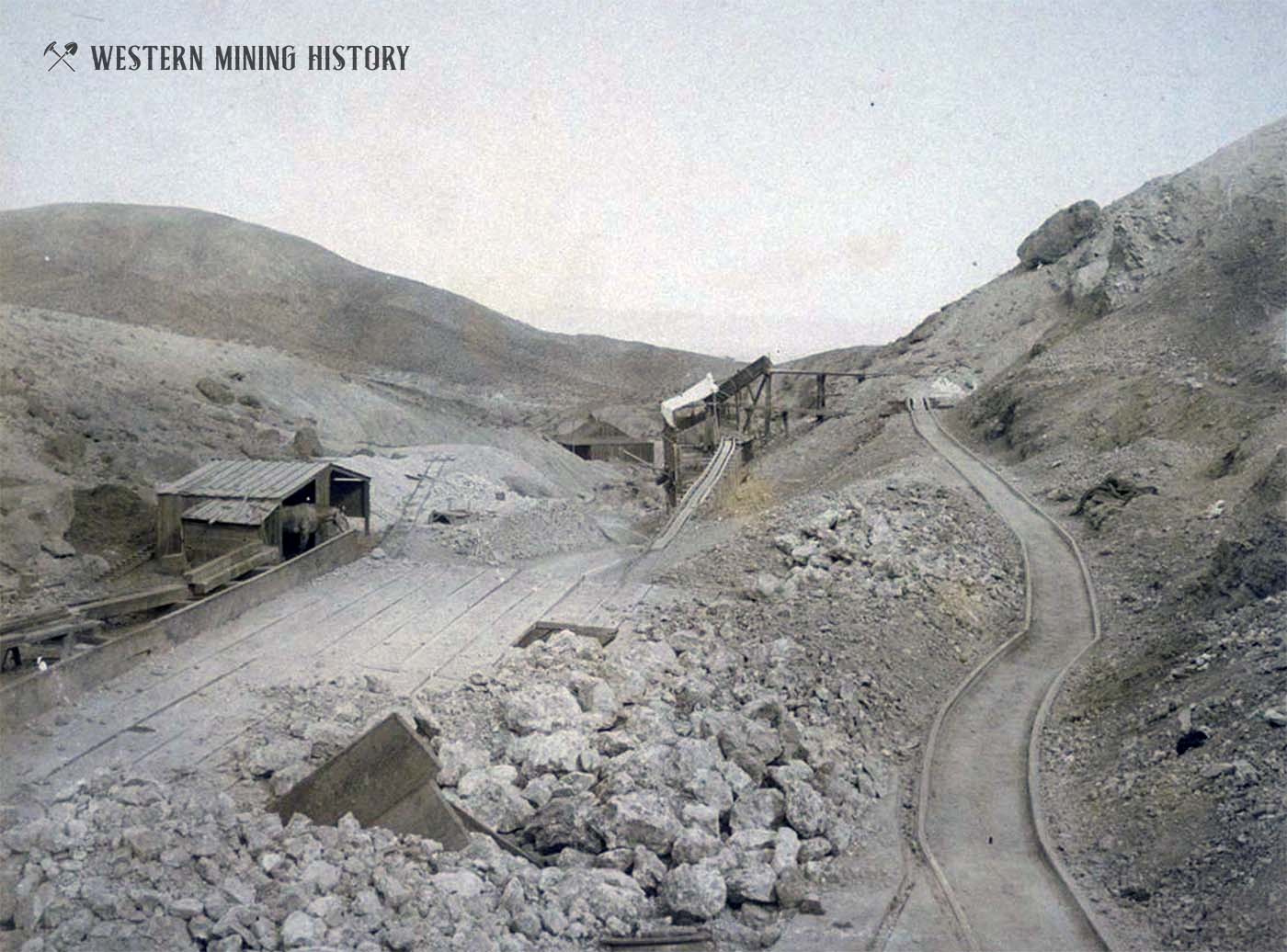

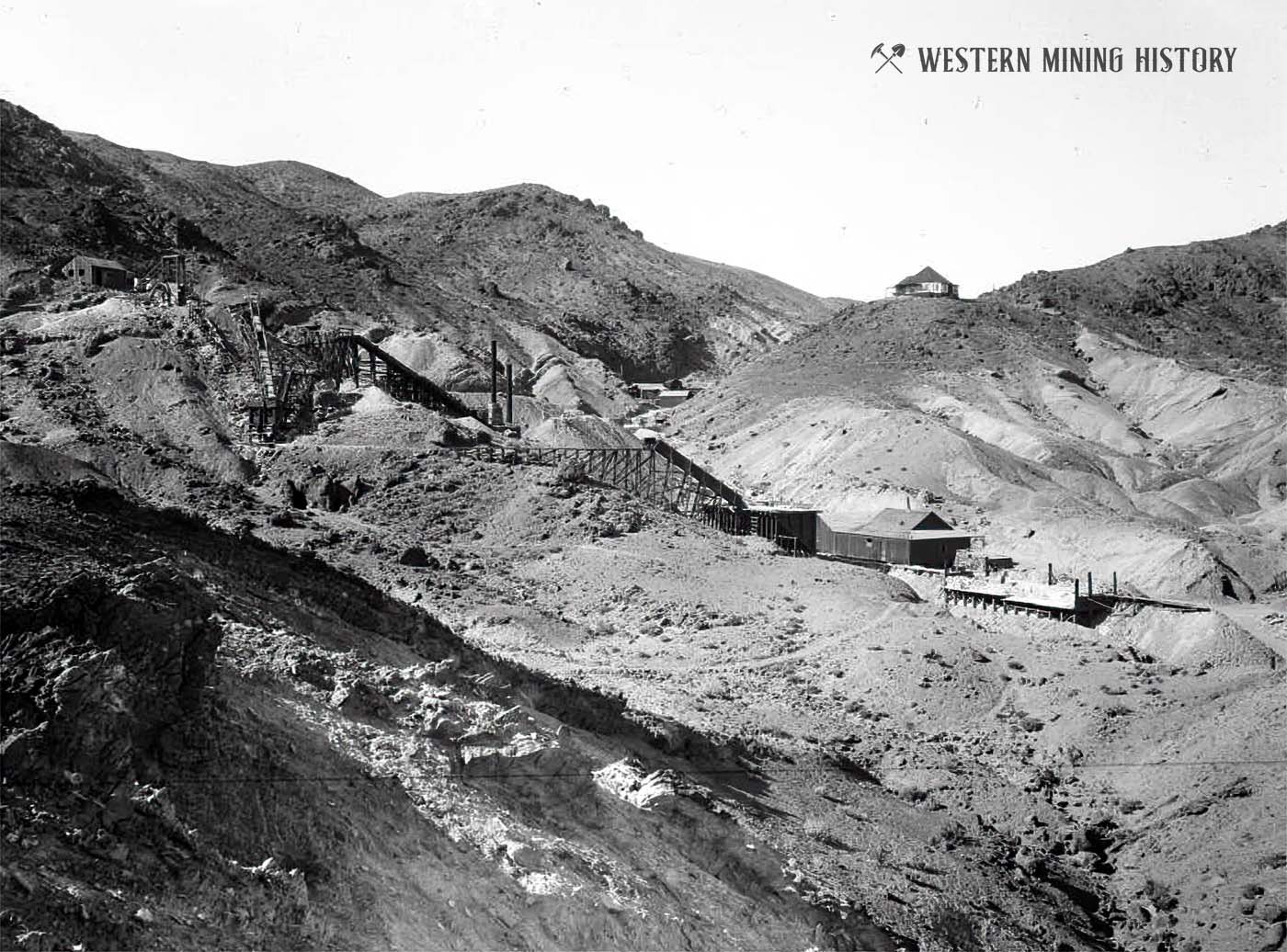

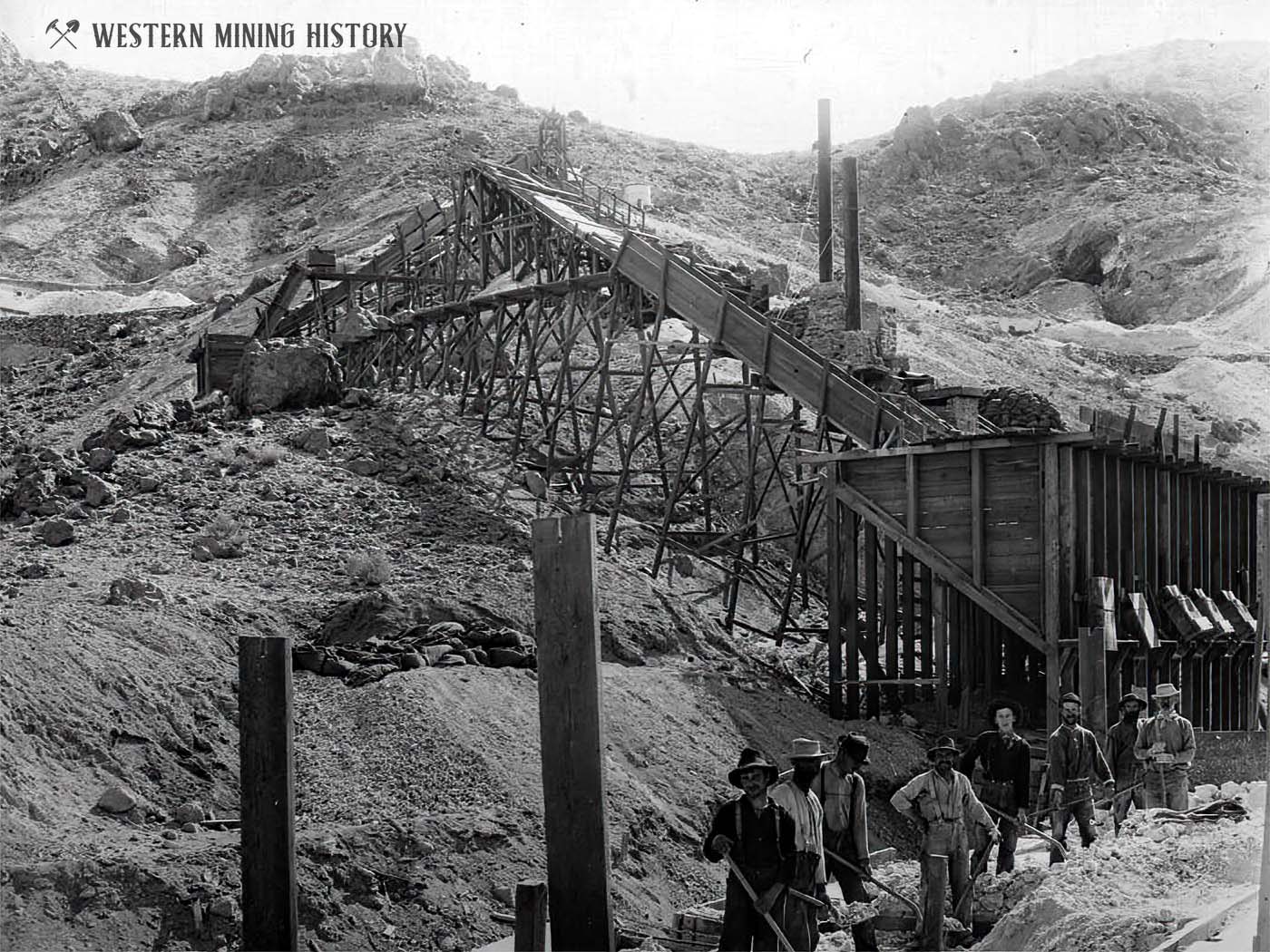

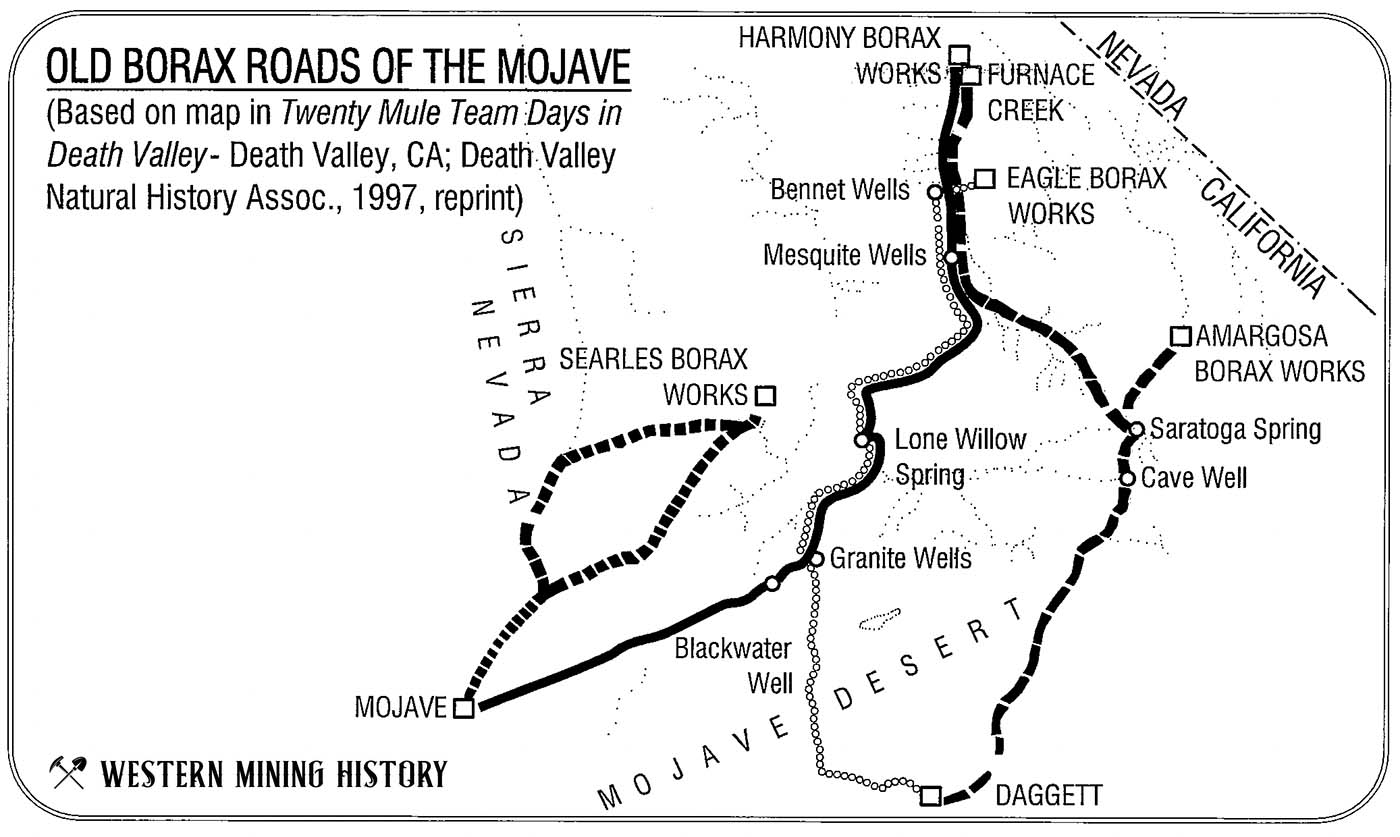

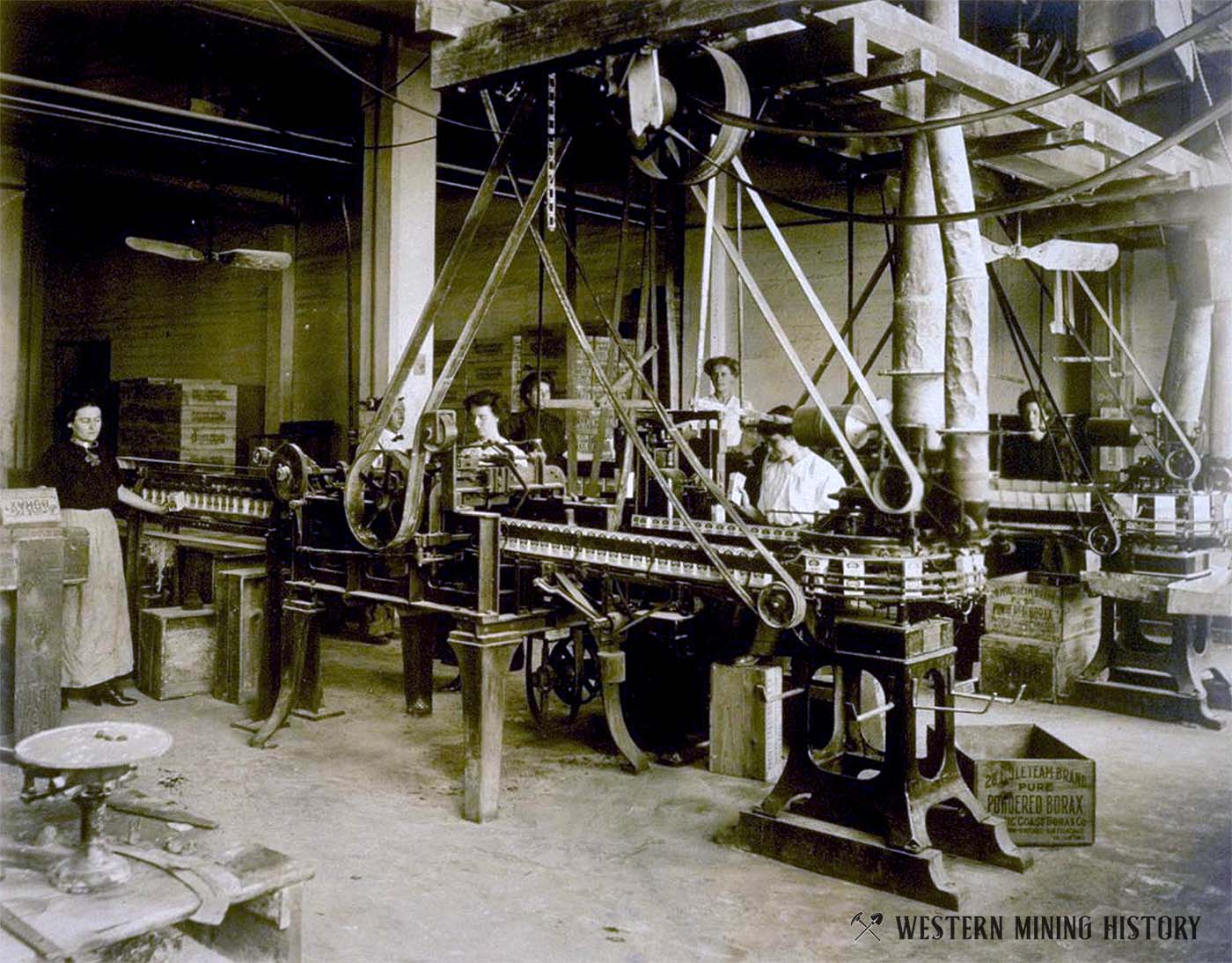

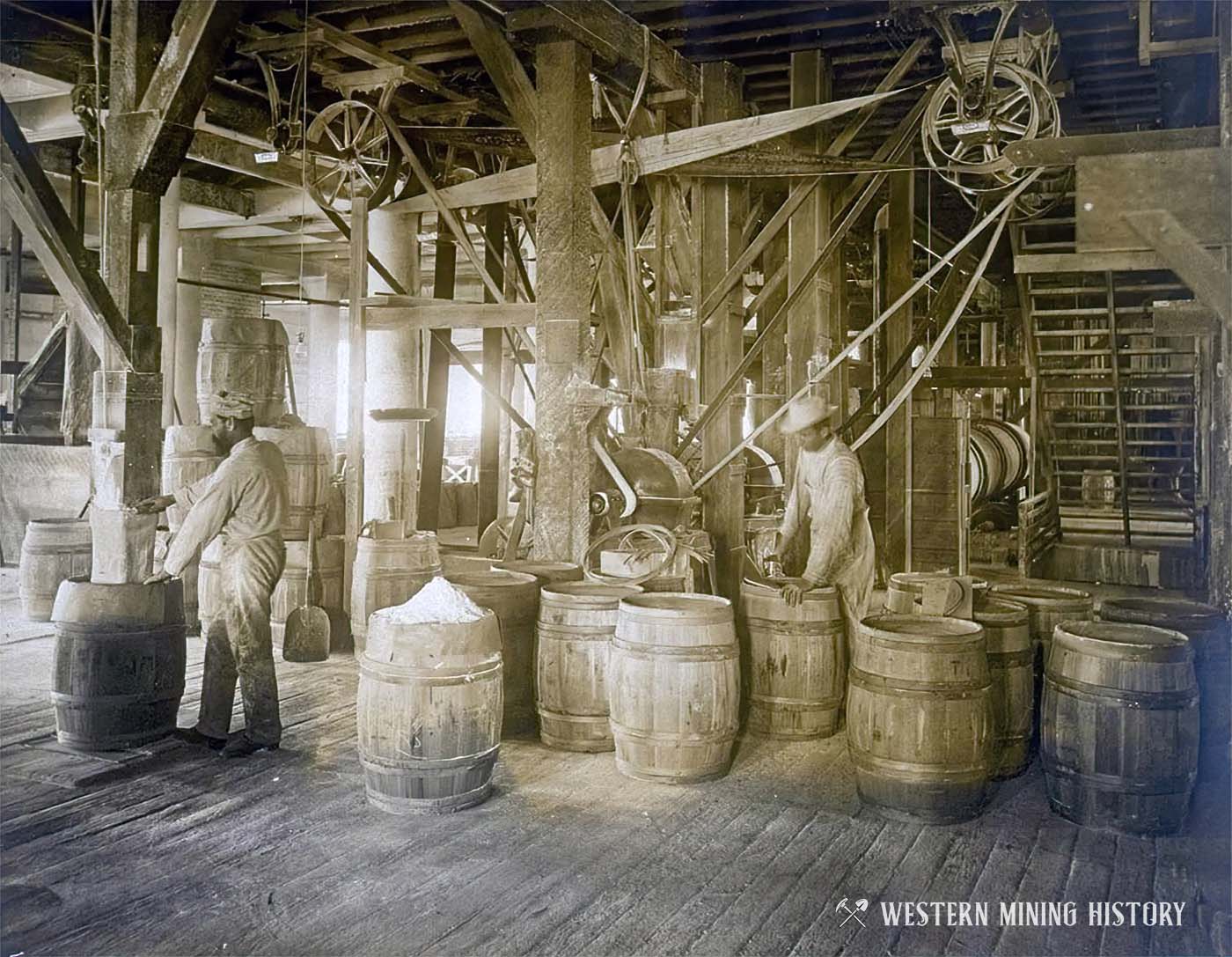

After he determined that what he had found was indeed borax, Winters sold his claim to William T. Coleman who established the Harmony Borax Works near Furnace Creek in 1883. With the help of Chinese laborers, he collected borax crystals, put them into large pans, and boiled them for as much as thirty-six hours before taking them out and putting them into vats where purer borax crystals formed.

Meanwhile a French adventurer named Isadore Daunet who had found a borax deposit twenty miles south of Winters’s a few years earlier, joined with a San Francisco broker, Gilbert Clemmons, and a local merchant, Myron Harmon, in establishing a borax mine at the site of his discovery.

Mining was difficult in the valley because of the heat, the lack of water and of wood for fires, and especially the scarcity of a means of transportation out of the isolated mines. For these reasons, the Daunet operation quickly failed, while the Harmony works was able to continue producing borax until 1888.

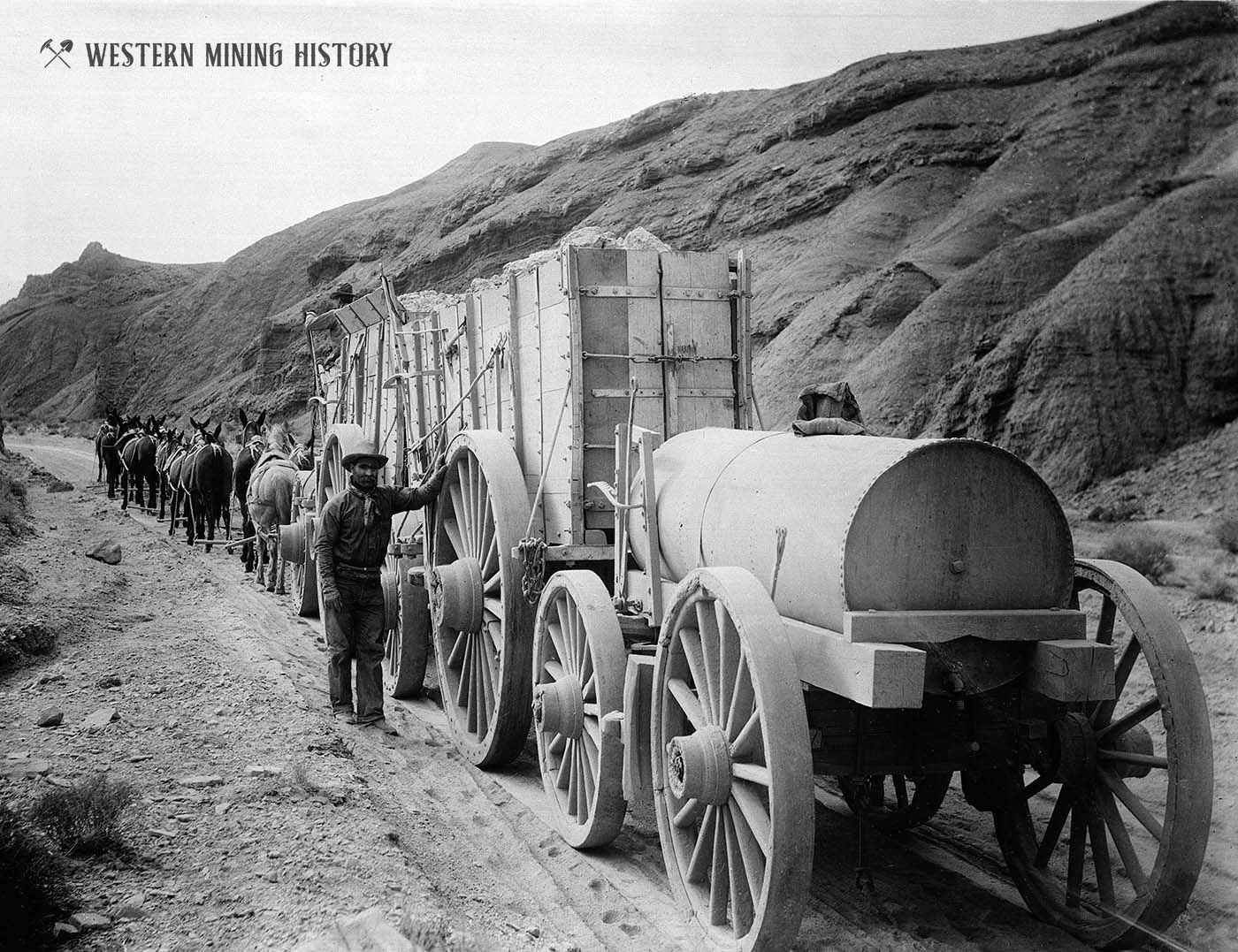

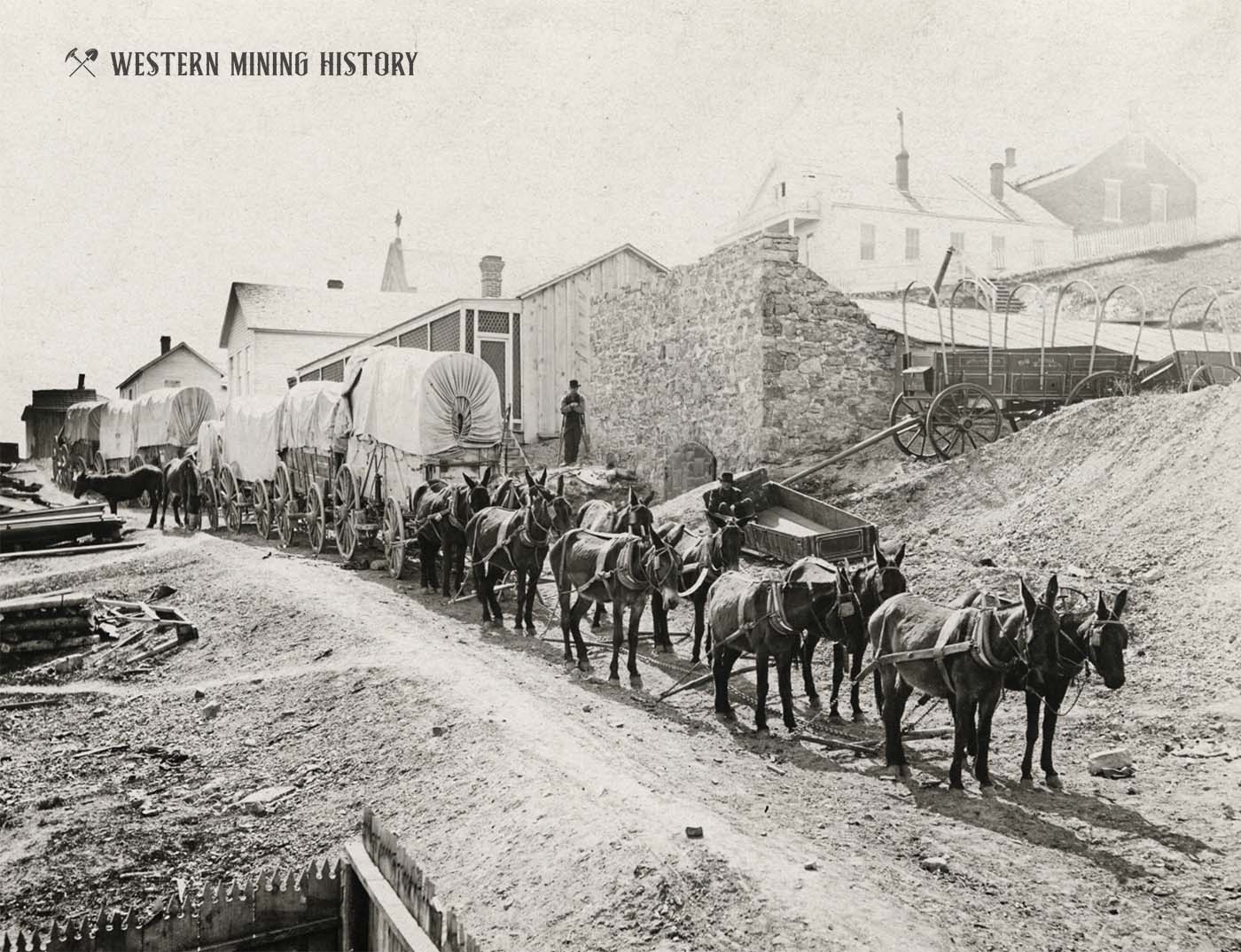

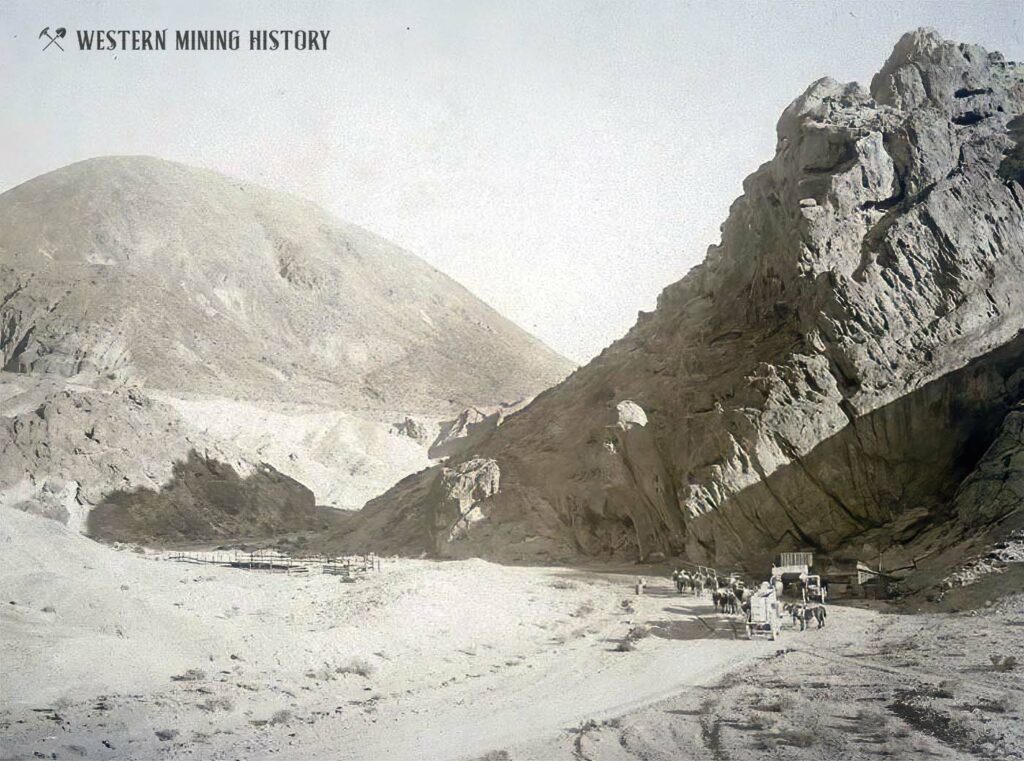

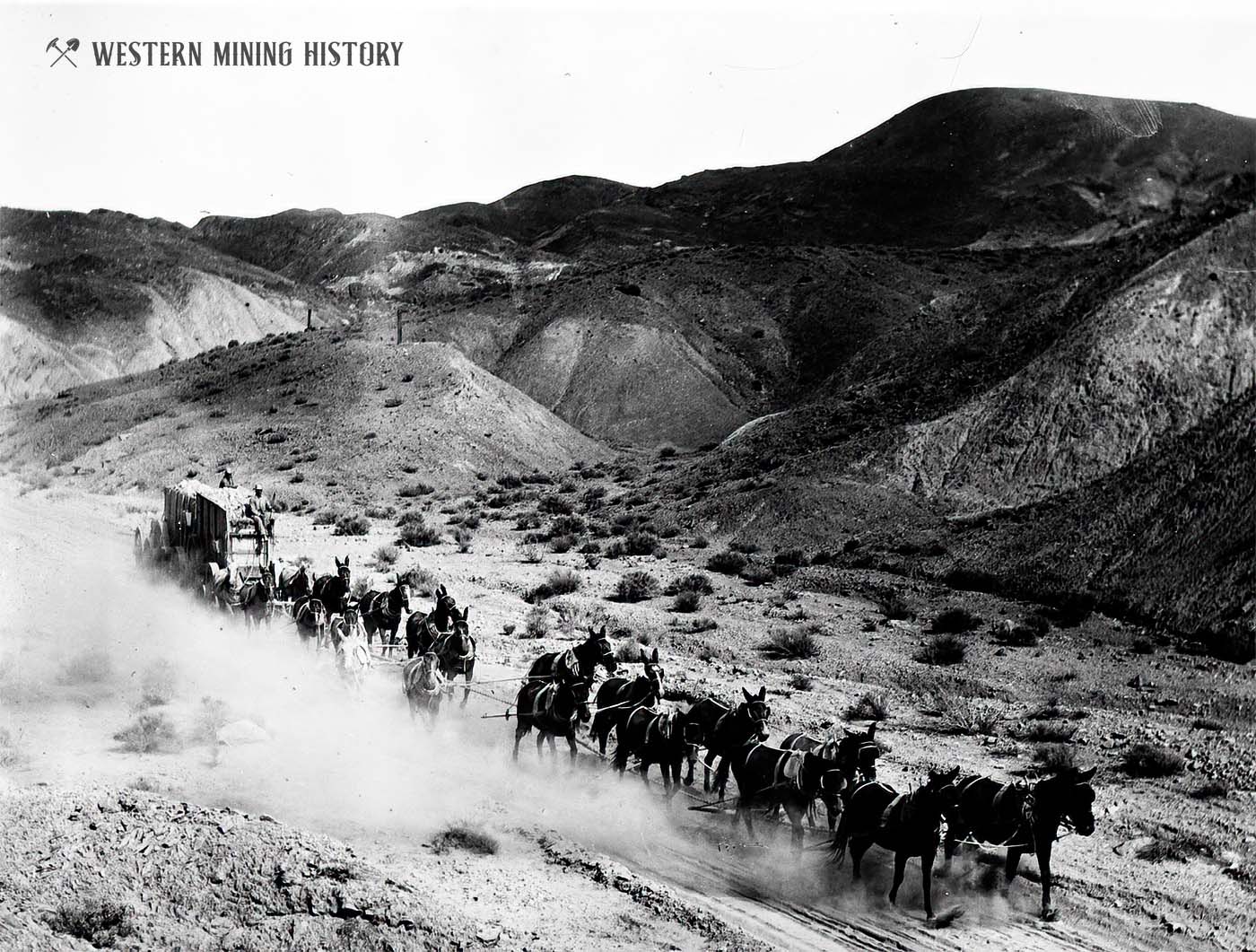

The Harmony Works became as famous for its trademark twenty-mule team wagons it used to transport partially refined borax to a railhead at Mojave, California as it was for its product.

The wagons and harnesses Coleman used were made from designs originating with John Searles, another Death Valley pioneer and early borax miner who formed the San Bernadino Borax Mining Company in 1873, taking borax crystals from the dry bed of what became known as Searles Lake.

Two years after Harmony ceased mining in Death Valley, Frank Marion “Borax” Smith acquired Coleman’s Furnace Creek works and Twenty Mule team brand name. Smith, originally from Wisconsin, had earlier discovered borax crystals at Teels Marsh in Nevada and established his first borax works there.

Borax Mining After 1900

Smith later founded the Pacific Coast Borax Company and moved his mining operations from Furnace Creek to Boron in the Calico Mountains south of Death Valley. There he began underground exploitation of colemanite deposits, a richer source of borax.

By 1901, Smith had begun investigating other borax mining claims and became interested in one in the Black Mountains east of Death Valley. He eventually located the Lila C. mine there, and the diggings in the Calico Mountains were closed in 1907.

That same year, Smith built the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad to service the Loa C. and other mines in the Death Valley area and connect with his borax refiners in California and the East. The railroad solved the transportation problem and over the years of its operation, the T&T also hauled lead, clay, and feldspar across the desert and provided passenger service.

The railroad operated until 1940 when its services were suspended. In 1943, its tracks were pulled up and their metal used in the country’s World War II effort.

For years the Billie Mine, an underground borate mine near Furnace Creek, was the only active mining operation in what is today Death Valley National Park. When it closed in 2005, formal mining in the park came to an end, (Death Valley had been formally declared a National Monument in February 1933 and a three million acre National Park in October 1994).

Today thirty percent of the world’s borax comes from the Rio Tinto Boron Mine, formerly the U.S. Borax Mine, and its open pit operation at Boron, California, south of the park.

John K. Suckow unearthed the borax deposit there in 1913 when drilling for water. He sold his claim to Smith’s Pacific Coast Borax Company, and mining at Boron began in the 1920’s. The company later became U. S. Borax, which in turn was acquired by Rio Tinto Group, an Anglo-Australian company said to be the world’s second-largest metals and mining corporation.

The company estimates boron at the mine site will last through 2050.

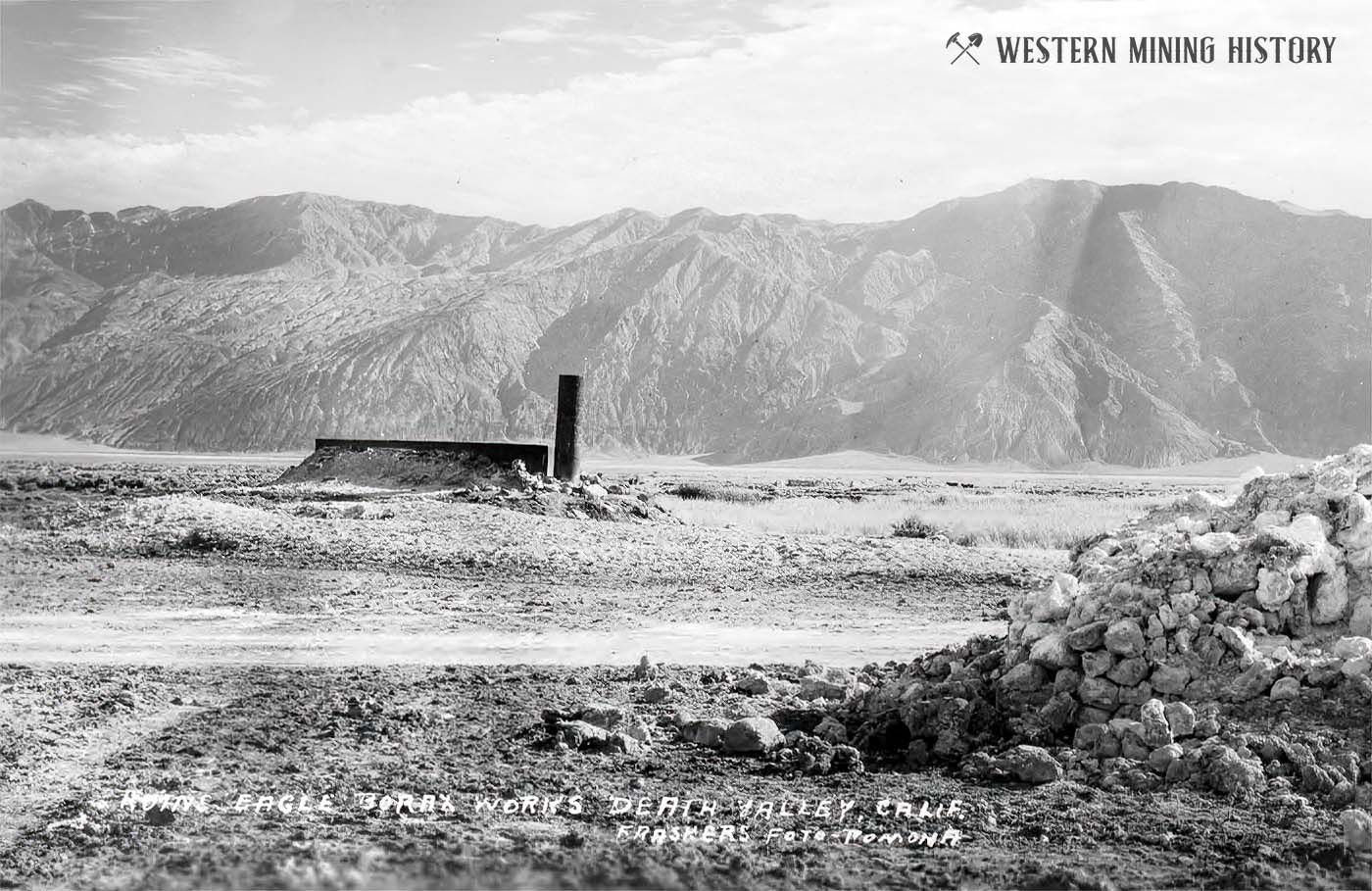

The Harmony Works site was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.

Related Articles

The following articles from Western Mining History explore more on the topics of Borax mining, Death Valley, and Freight teams.

The Twenty Mule Teams of Death Valley

The Twenty Mule Teams of Death Valley presents text and diagrams from a series of reports by the Historic American Engineering Record. Included are historical images of these iconic western wagon teams.

Death Valley’s Harmony Borax Works

Death Valley’s Harmony Borax Works operated during the 1880s. The borax operations of Death Valley made the “20 Mule Teams”, the wagon trains that hauled the finished borax across the desert, famous in American culture.

Heavy Freight Wagons

Freighting in the West was one of the most essential jobs, yet it is rarely talked about today. Heavy Freight Wagons of the American West examines the men, wagons, and animals that provided this important service to frontier mining towns.