The text and black and white diagrams in this article are from a series of reports from the Historic American Engineering Record. Additional images are from the Library of Congress and various archives.

Borax was discovered in Death Valley in 1880 by Aaron Winters and his wife Rosie. A prospector staying overnight at the Winters’ home told them about finding borax in Nevada, which intrigued Winters. Consequently, he and Rosie searched for borax in Death Valley. After finding a deposit, Winters contacted William T. Coleman of the borax company Coleman & Smith, who sent two representatives to purchase the site.

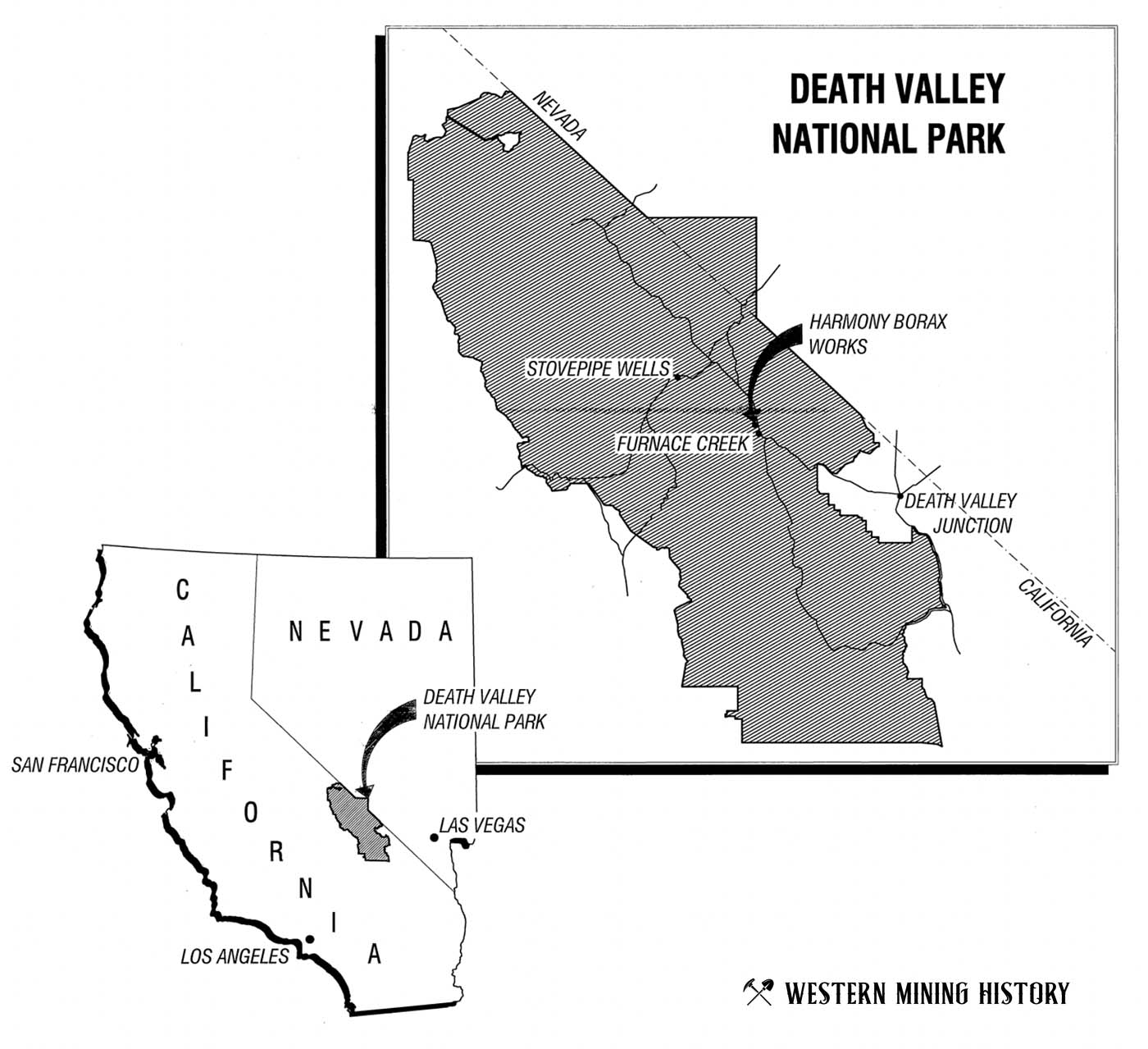

The company then established a borax mining operation that came to be known as the Harmony Borax Works. The “cottonball” borax at Harmony was mined by Chinese laborers from San Francisco and processed at the works. There was also another nearby operation known as Eagle Borax Company, but it closed due to financial problems and the suicide of the owner, Isadore Daunet.

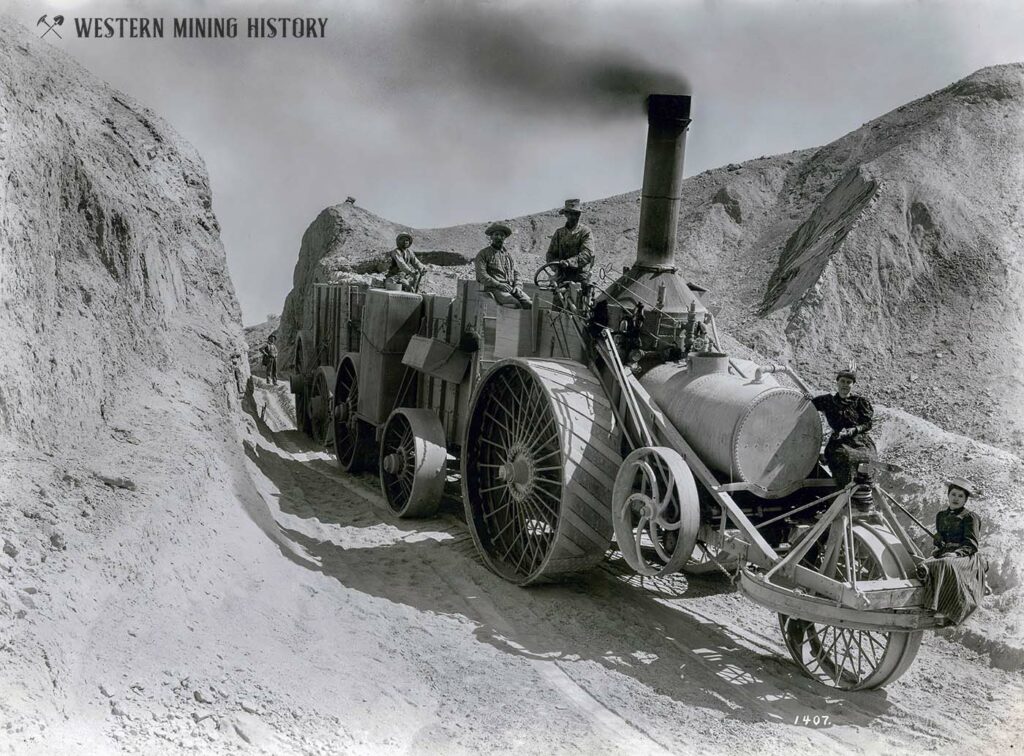

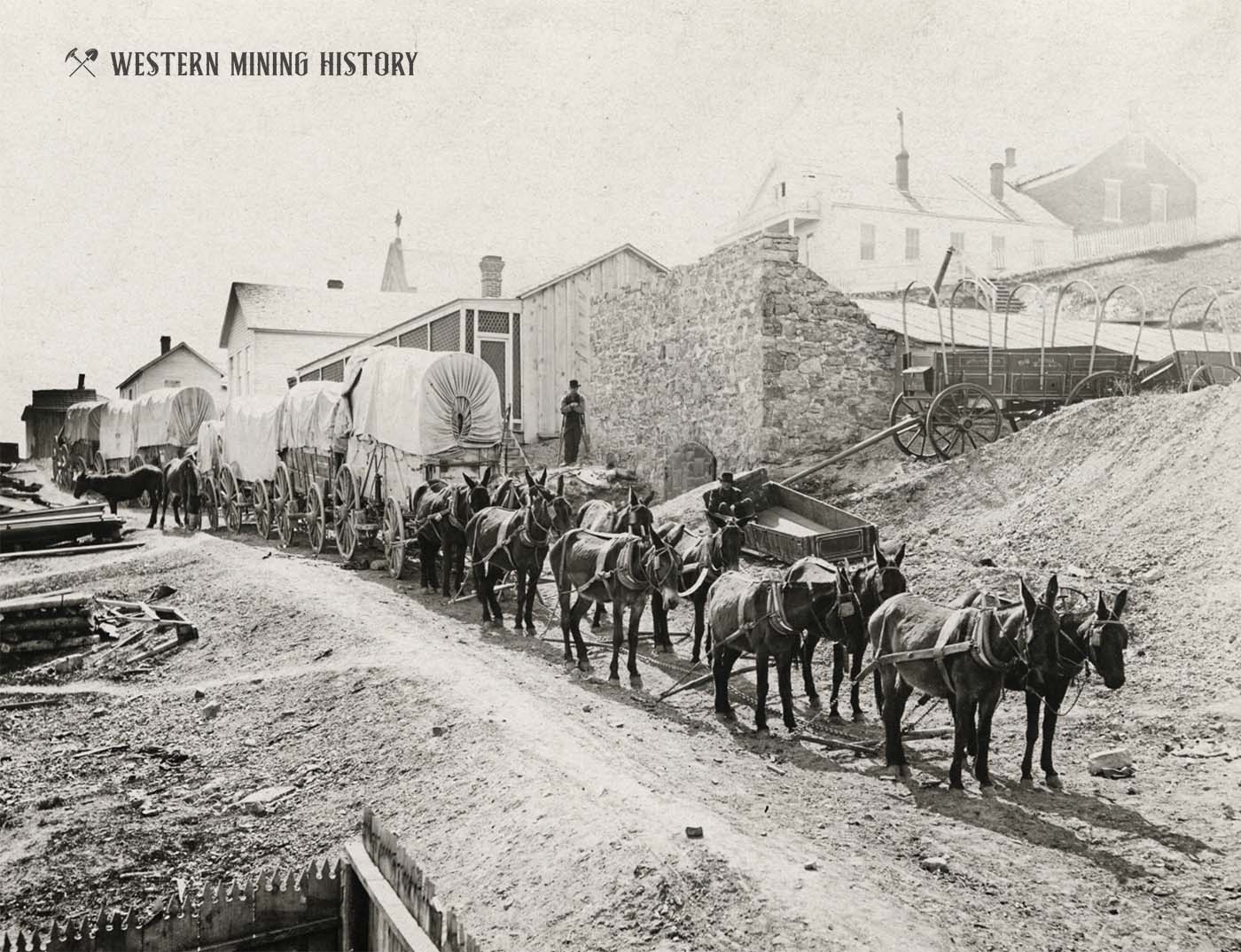

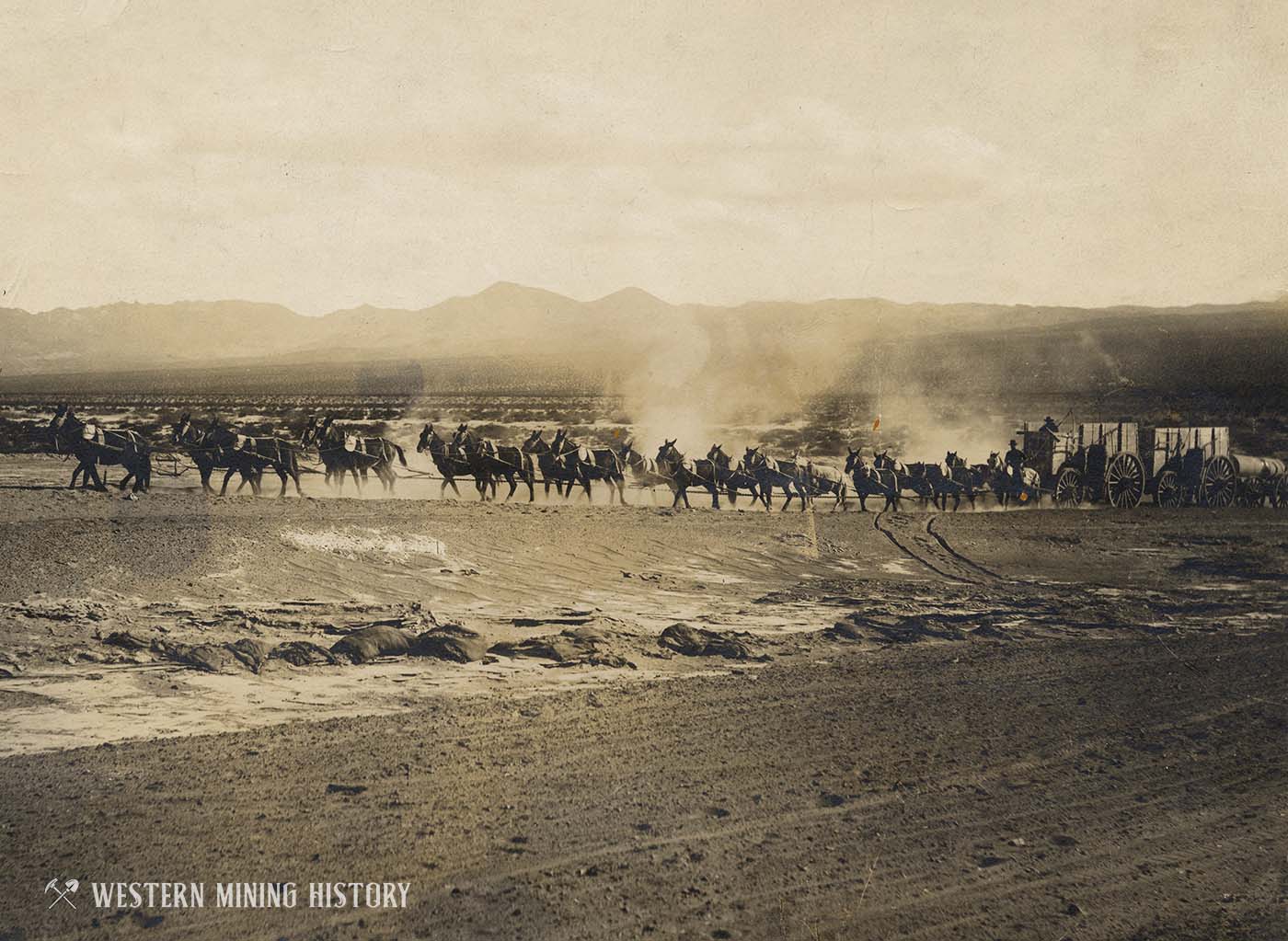

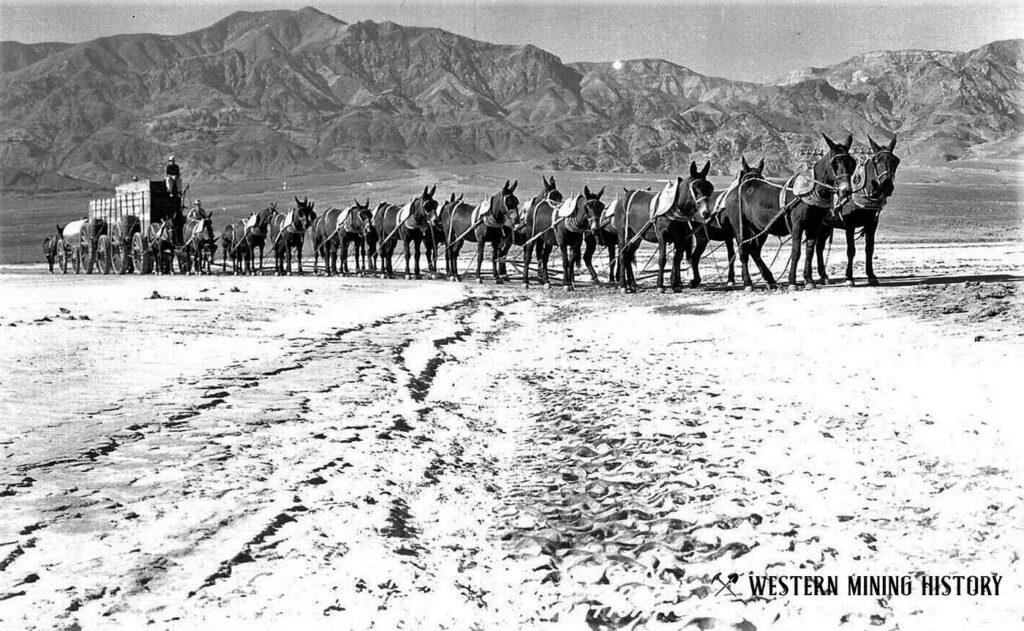

After processing the borax, it had to be transported across the harsh terrain to the Mojave station on the Southern Pacific Railroad. There are conflicting ideas as to the origins of the twenty mule team borax wagons used in Death Valley. In order to save money, William Coleman reportedly decided that it would be most cost effective for the company to do its own transporting.

According to most sources, J.W.S. Perry, superintendent of Harmony, decided that bigger wagons were needed than those used in other borax operations because of the terrain. Perry then learned about wagons and began to create a wagon that could carry 10 tons and handle the rough paths.

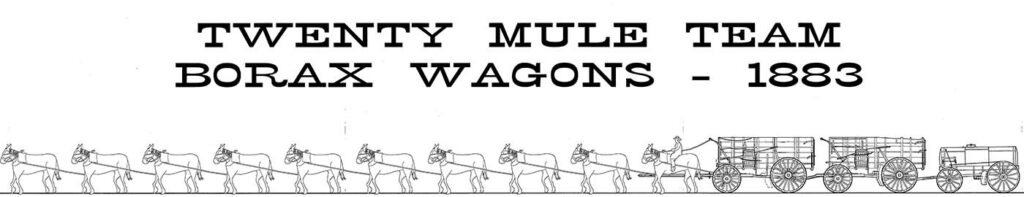

Regardless of the actual number of animals, the twenty mule team wagons became an advertising icon and thus became an enduring symbol of the American West.

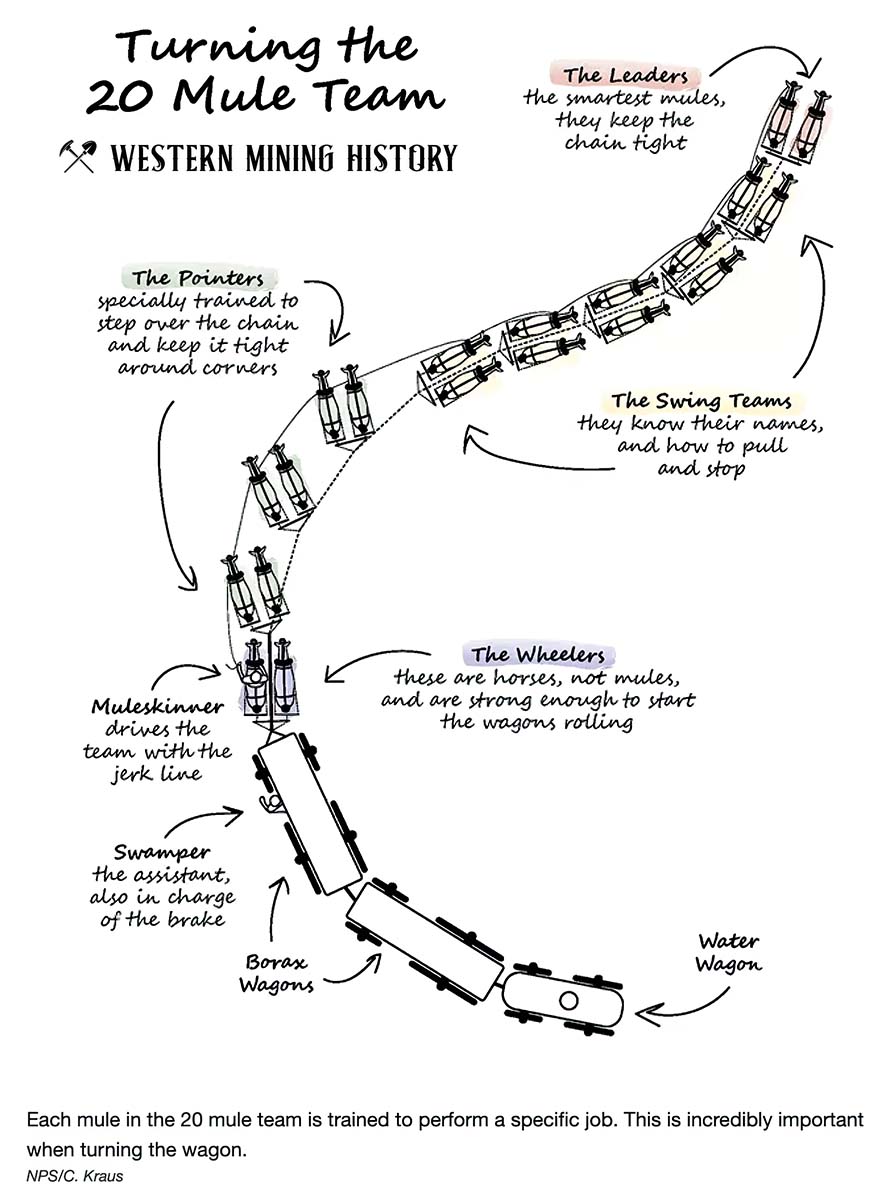

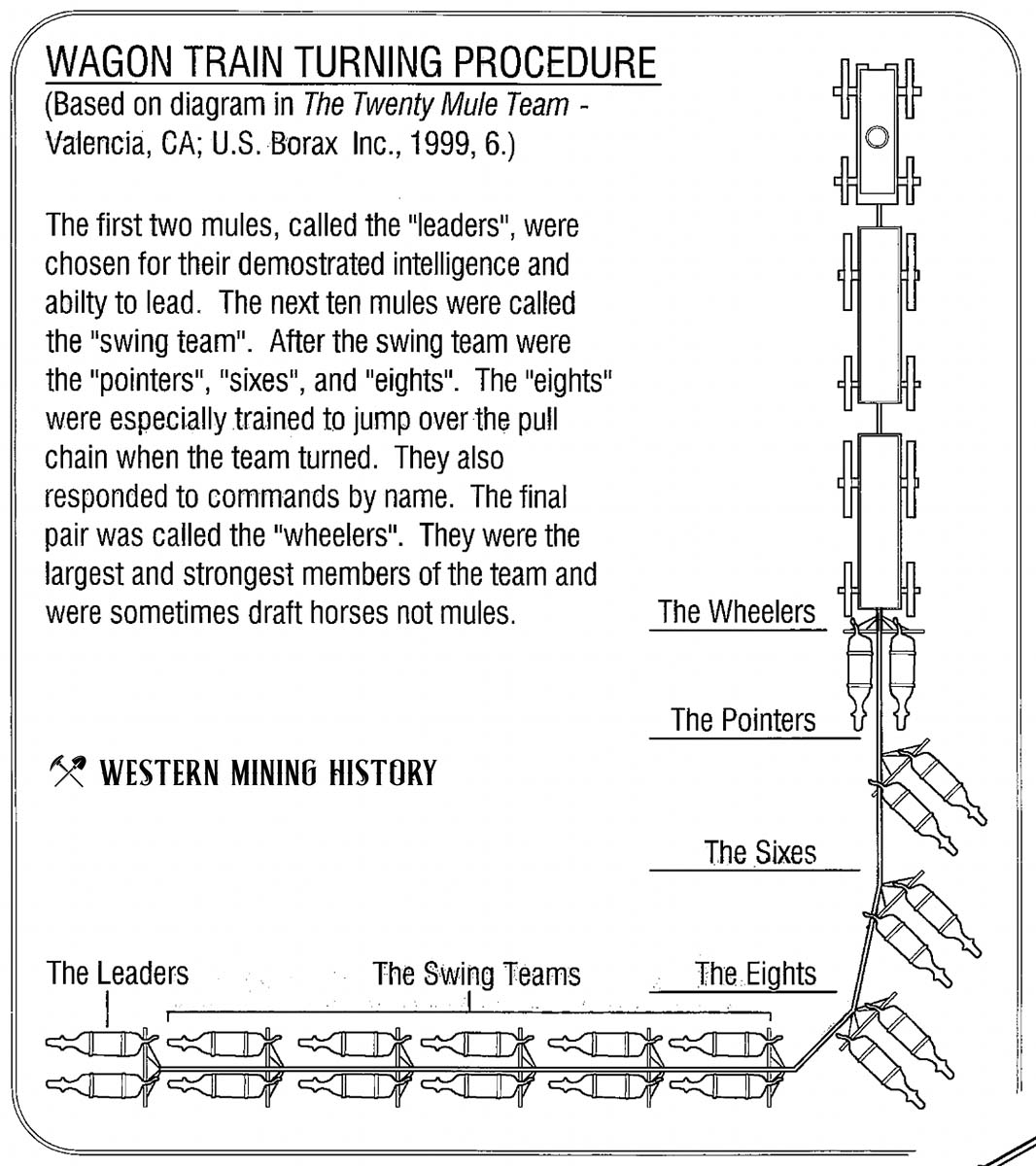

The number of animals used on the wagons is a source of contention as well. The popular account is that Edward Stiles, a driver, and Perry combined a twelve mule team and an eight mule team with two wagons and a water wagon, thus creating the twenty mule team borax wagons. Other sources note that there were actually eighteen mules and two horses, whiles others contend that there were only eighteen animals total used.

The Twenty Mule Team Brand

The idea of using the team as a method of advertisement came from Stephen T. Mather, who later would be the director of the National Park Service, as he tried to come up with a way to make borax known as a household product. Borax was used throughout the nineteenth century in glass, enamel, and glazes. By the end of the nineteenth century, it was used in a variety of household products.

One article described some of its uses as cockroach exterminator, laundry detergent, shampoo, and toothpaste. Its useful household properties needed to be demonstrated to encourage an increasingly consumer society to purchase the product. The strategy Mather designed emphasized the mule teams rather than the name or trademark of the Pacific Coast Borax Company for whom he worked.

Accordingly, the twenty mule teams were exhibited around the country, such as at the 1903 St. Louis World’s Fair. Signifying the American West and the pioneering miners who embodied masculinity and the quest for material wealth, the twenty mule team wagons ultimately had a cultural significance that outlasted any technological innovations.

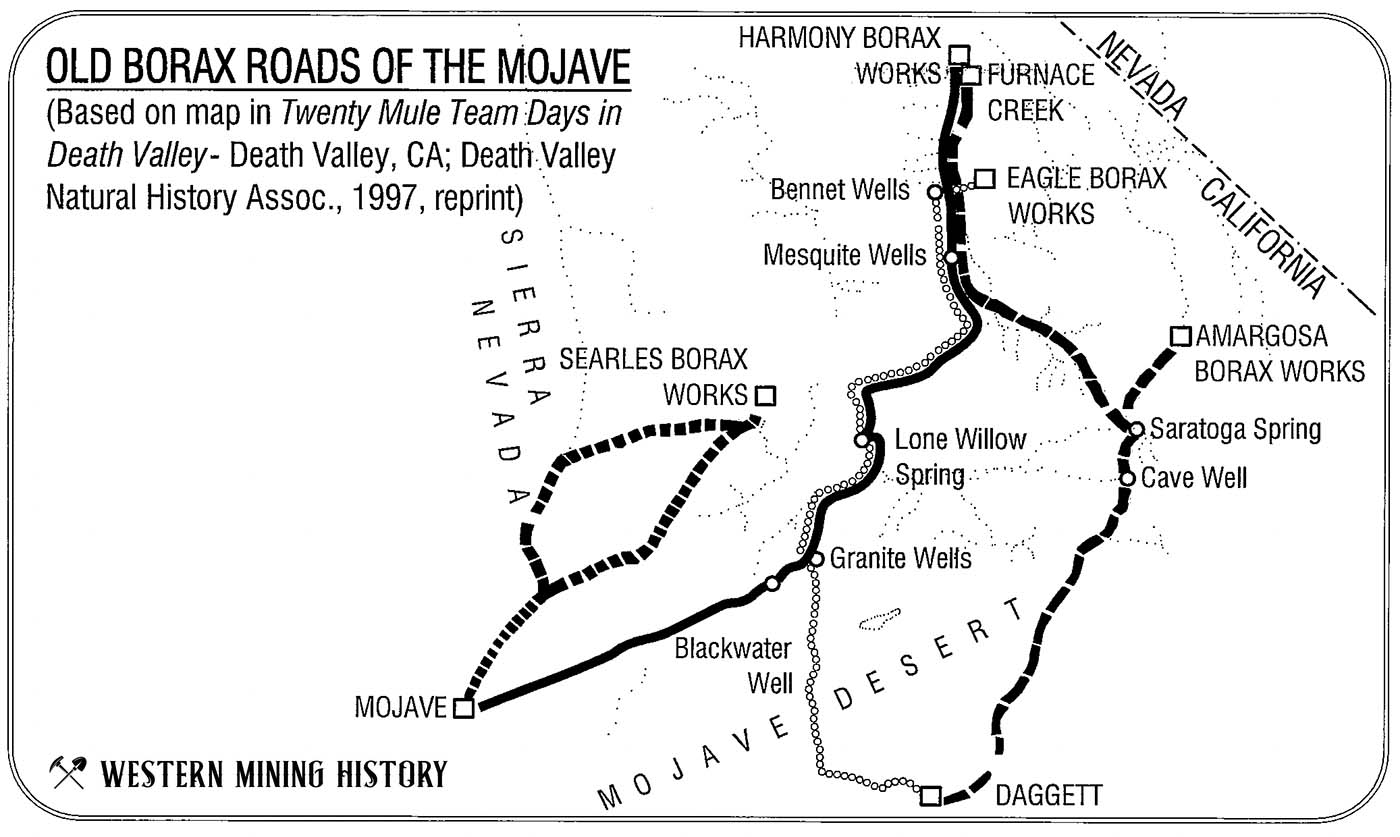

Borax Roads of the Mojave

The 165 mile route from the Harmony Borax Works to the Mojave station consisted of tortuous terrain punctuated by stations at water sources. The route is reported to have been laid out by J.W.S. Perry. Due to the heat of the summer months, however, an alternate route had to be used that took the wagons to the town of Dagget.

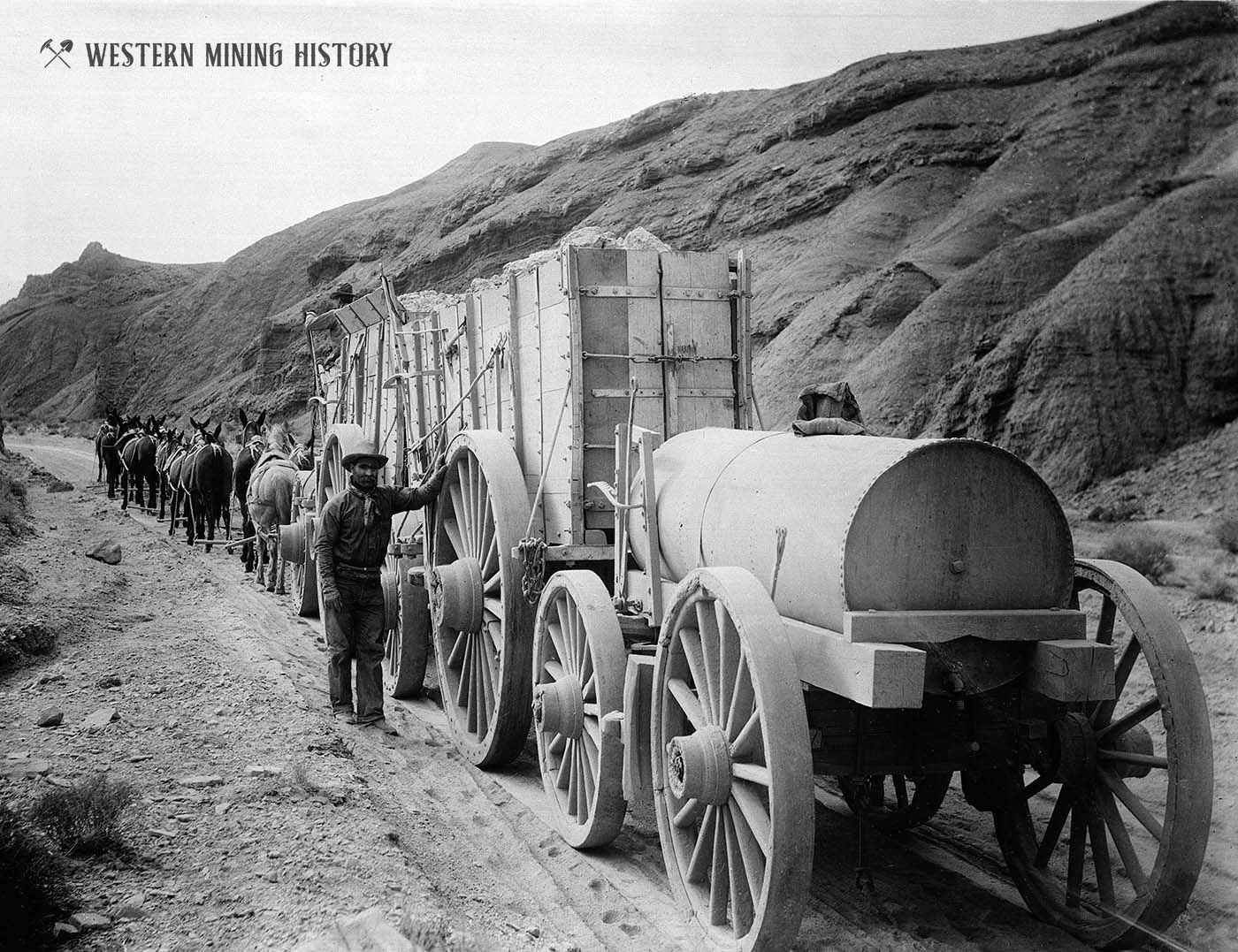

As the twenty mule team borax wagon made its way across the desert, it could travel approximately 17 miles a day. The driver, therefore, had to plan the travel to coordinate with stations, at which two to four feed boxes were available to the animals and water was available for all.

There were generally only two people who accompanied the team: the “muleskinner,” also known as the driver and teamster, and the “swamper.” The muleskinner not only drove the team but also served as veterinarian and mechanic, for which he earned $100 to $200 a month. The swamper assisted the muleskinner and performed other tasks like cooking dinner and unharnessing the mules. His salary was lower at $75 a month.

Perhaps the most famous muleskinner was Bill Parkinson, also known as “Borax Bill,” who had a reputation as the best since he exhibited the necessary traits of patience, forcefulness, and skillfulness. He became well-known later in his career as a bit of a prima donna as he traveled the country exhibiting the twenty mule team wagons.

The Borax Wagons

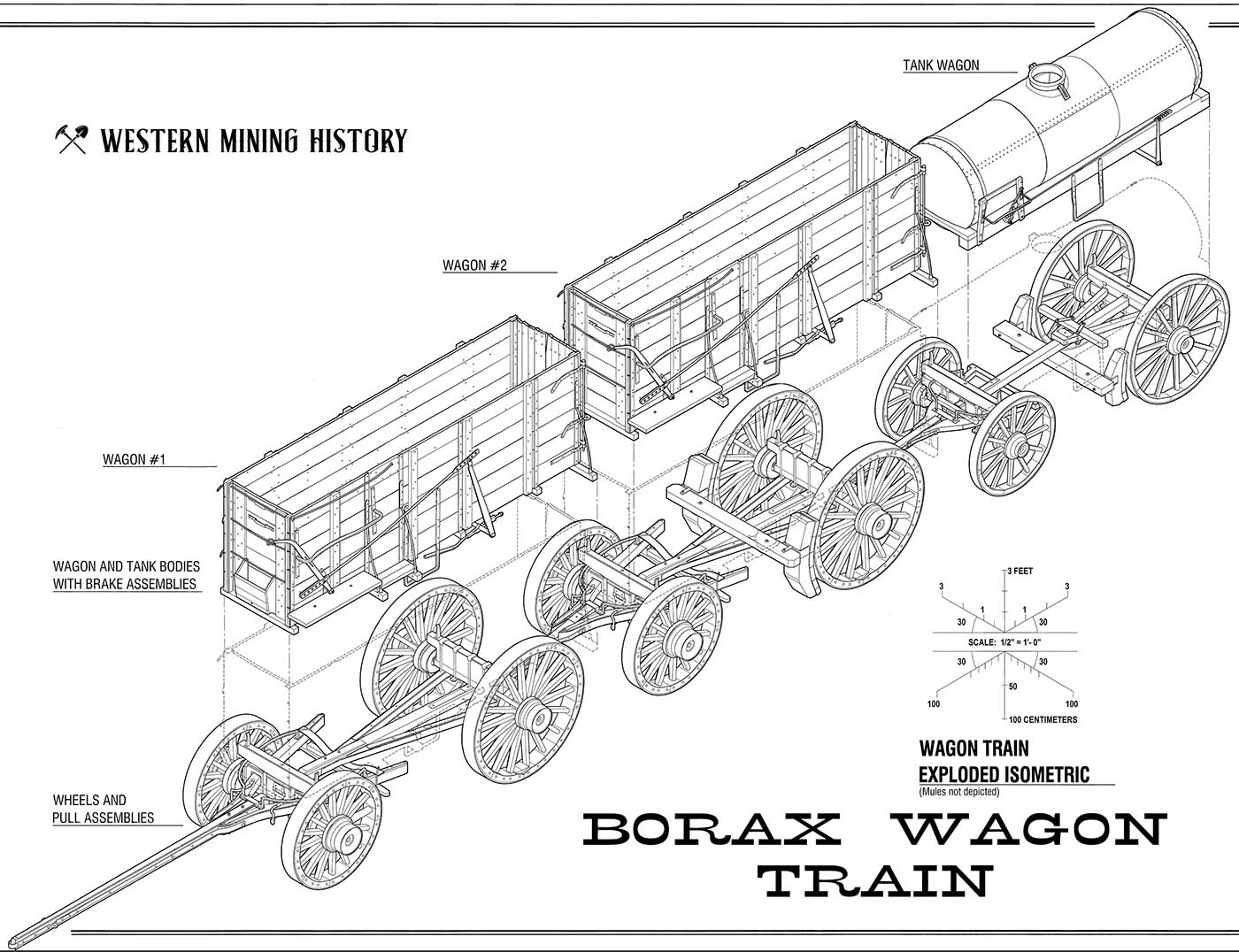

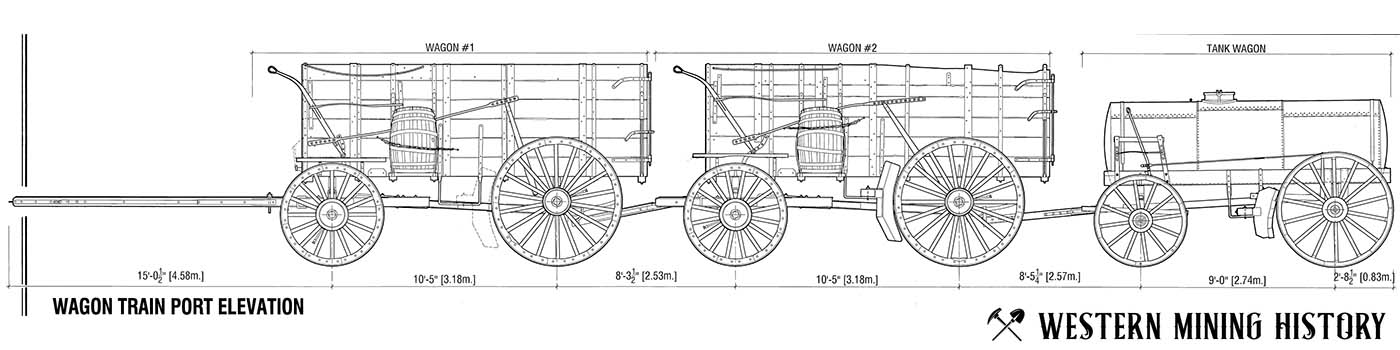

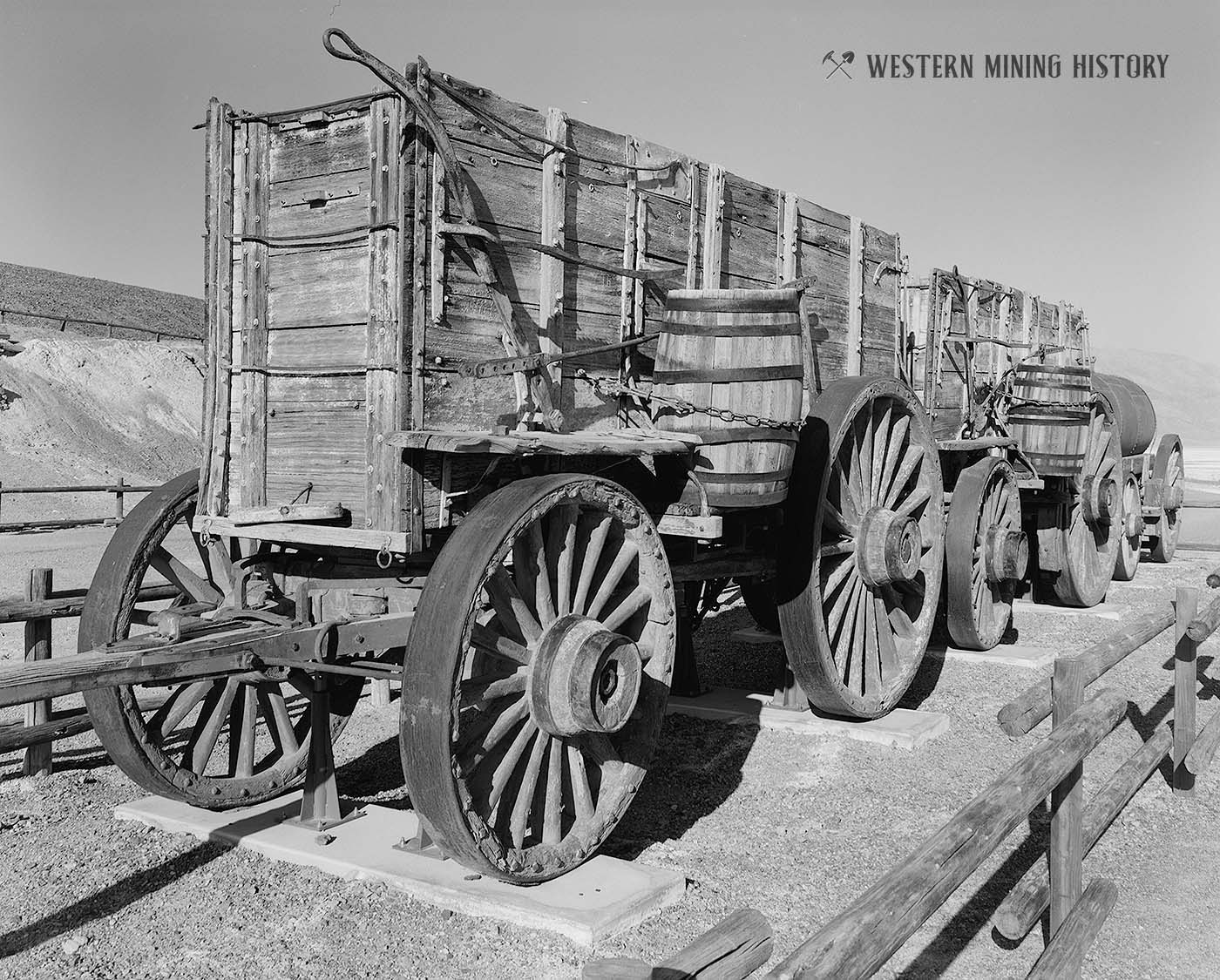

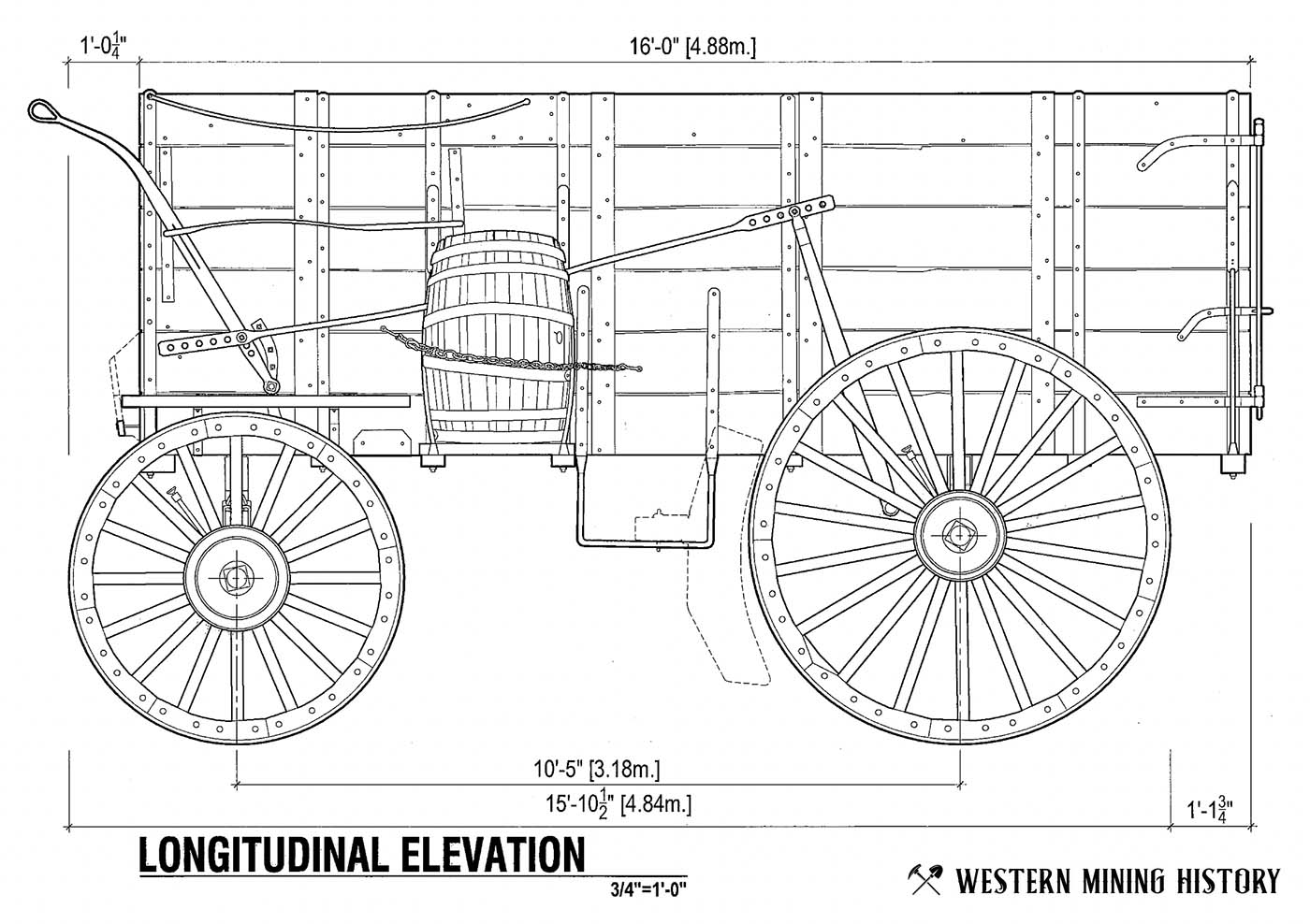

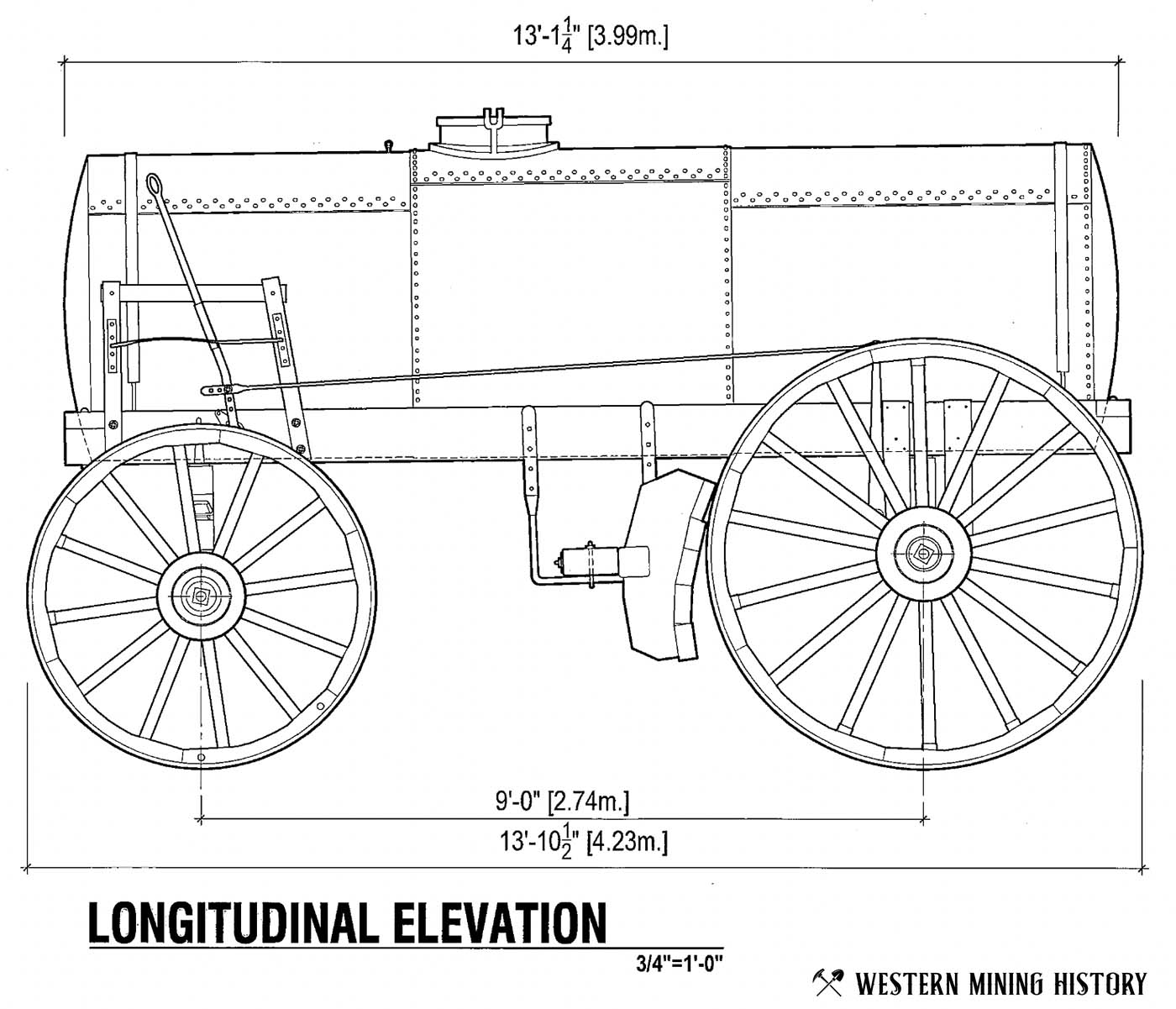

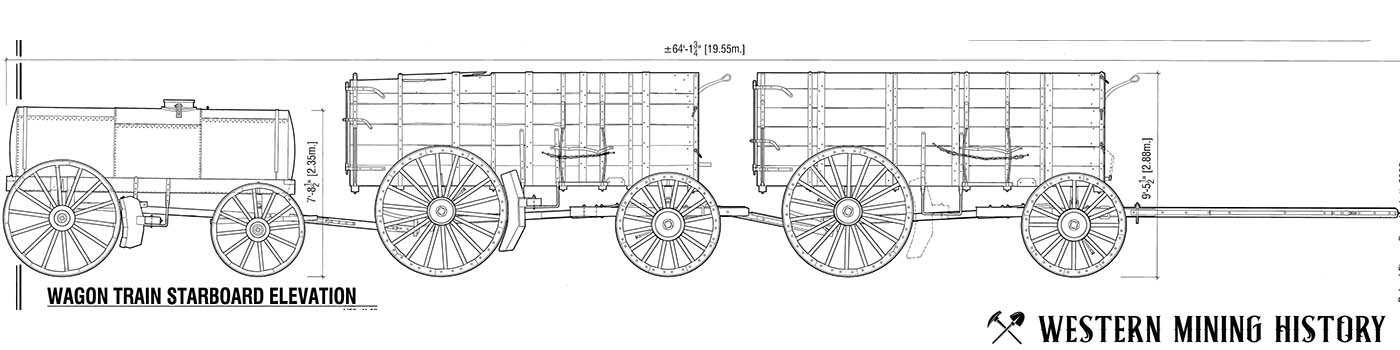

J.W. Spears’ Illustrated Sketches of Death Valley and Other Borax Deposits of the Pacific Coast provides the most complete descriptions of the borax wagons. The wagon train itself consisted of two wagons, which were 16′ long, 4′ wide, and 6′ deep, and weighed 7,800 pounds when empty.

The rear wagon wheels had a 7′ diameter and the front ones had a 5′ diameter. The iron tires had dimensions of 8″ wide and 1″ thick and weighed approximately 1,000 pounds. The spokes, made from split oak, were 5 1/2″ wide to 4″ wide at the point. When looked at it in cross section, the forward axle trees were 3 1/4″ square and constructed of solid steel bars. The rear axles were 31/2″ square. It was vital that the wheels be well-maintained given the terrain.

The wagons must have been well-built because in the five years of their use from 1883 to 1888 they hauled more than 15 million pounds of borax without breaking down.

Driving the wagons was another story. It required a complex system of harnesses and a “jerk line” that controlled the whole team. A steady pull by the driver told the animals to turn left while a series of jerks indicated right. To stop the team, a voice command as well as the brake were used. Turning the wagon was a complicated maneuver, requiring the mules to jump over the chains that connected them to keep the wagon from swinging out of the turn.

The Water Wagon

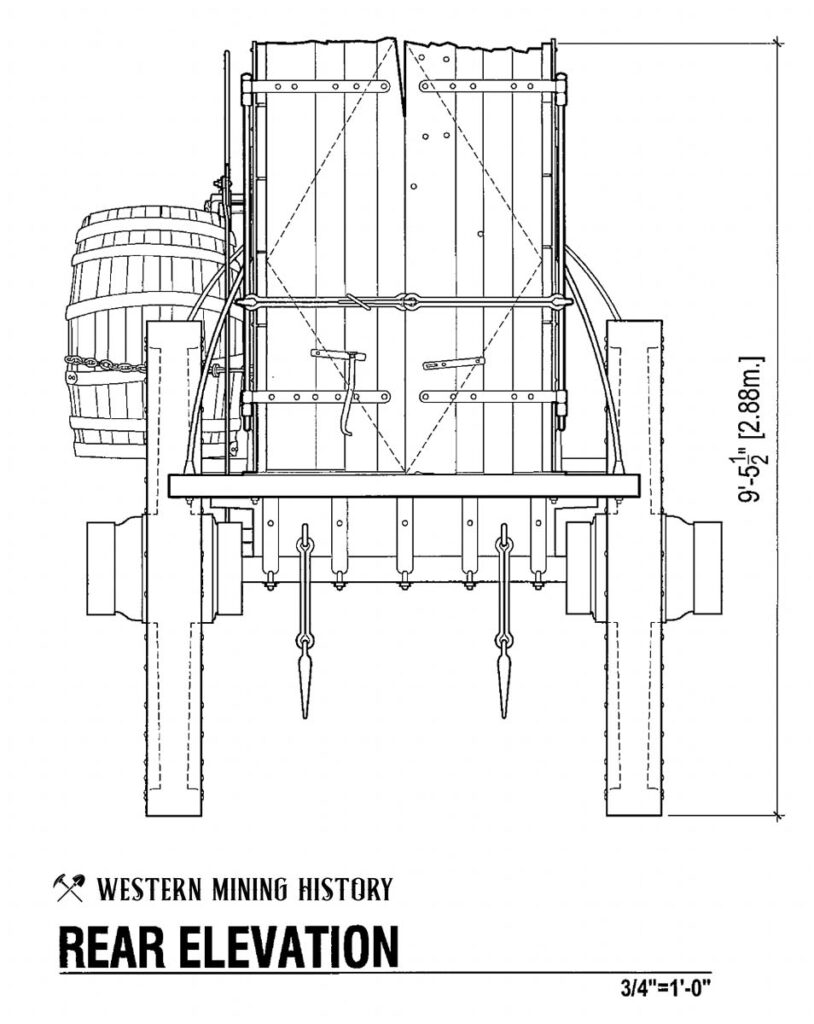

The water wagon attached to the end of the wagon train represents an adaptation to the dry climate of Death Valley. Since the trek from Harmony Borax Works to Mojave Station contained stretches with no available water, the water wagon fulfilled a basic need.

Made of iron since wood could fall apart, the wagons carried 500 to 1,200 gallons of liquid. They were taken from springs to dry camps on the route to Mojave Station and back to springs to be filled. It is unclear from available sources if the water wagon was a permanent feature of the train or if it was left at dry stations.

The harsh environmental conditions stressed both human and animals. One driver named Salty Williams described the difficulties of the journey, as recorded by Mary Hunter Austin in The Land of Little Rain: “Hot days the mules would go so mad for drink that the clank of the water bucket set them into an uproar of hideous, maimed noises, and a tangle of harness chains.”

Salty, meanwhile, would curse and yell at the mules until they were silenced. After his swamper died, Salty quit his job because it was “too durn hot.” Yet he took up the job again because of the “call of the land.”

Related Articles

The following articles from Western Mining History explore more on the topics of Borax mining, Death Valley, and Freight teams.

History of Mojave Desert Borax Mining

Borax mining in Southern California’s Mojave Desert was made famous by the twenty-mule team wagon trains that were used to transport borax across the desert. History of Mojave Desert Borax Mining takes a look at the history of borax mining in California.

Death Valley’s Harmony Borax Works

Death Valley’s Harmony Borax Works operated during the 1880s. The borax operations of Death Valley made the “20 Mule Teams”, the wagon trains that hauled the finished borax across the desert, famous in American culture.

Heavy Freight Wagons

Freighting in the West was one of the most essential jobs, yet it is rarely talked about today. Heavy Freight Wagons of the American West examines the men, wagons, and animals that provided this important service to frontier mining towns.