From Harpers New Monthly Magazine, 1888 by Edwards Roberts

The territory of Montana is in itself an empire. It was given Territorial rights in 1864, and since then has increases rapidly both in wealth and population. Fabulously rich in mines, already having an annual output of nearly $26,000,000, it is famous for it's vast areas of grazing land and becoming widely known as an agricultural country. With a total area of 93,000,000 acres of land, of which 16,000,000 are agricultural, 38,000,000 grazing, 12,000,000 timber, 5,000,000 mineral and 22,000,000 mountainous, it is the source of the Columbia and Missouri, and has an almost innumerable number of smaller streams, whose presence in the mountain canons and in the valleys give the Territory a charming picturesqueness.

Within a distance of from twenty to forty miles of Helena are thousands of mining claims yet to be developed, anyone of which may prove as rich as the richest of those that are now productive. If the several agricultural valleys were places in a continuous line, they would form a belt 4000 miles long, and averaging from miles in width. Every year the number of farms increases. In the Gallatin, Prickly-Pear, Yellowstone, Bitter Root, Sun River and other valleys, one no longer sees neglected fields.

But if one were to write in detail of Montana and it's resources, he would find the task an arduous one. There are so many valleys, each with it's own claims and characteristics, so many mines and towns and districts, that a volume might be devoted to each. There is great and general buoyancy among the people, and local prejudice runs high.

Regarding Helena and Butte, however, there is almost a unanimity of feeling. The two places are looked upon as perfect illustrations of what has been accomplished in the Territory since the age of development began.

To the younger generation Helena is a Parisian-like center which he hopes in time to see. Capitalists may make their money at Butte or elsewhere, but are moderately sure to spend it at Helena; and the miner or ranchman is never so happy as when he finds himself in what, without question, is the metropolis of the Territory. I know of no city in the extreme middle west that could so well satisfy one who had learned to appreciate Western life as Helena. It's climate, its surroundings, even its society, largely composed of Eastern and college bred mean and young wives fresh from older centres, are delightfully prominent features. The city has a population of nearly 15,000 and considering its great wealth, it is not surprising that it should have electric lights, a horse-car line, and excellent schools.

Thanks to the railways, which have had and are continuing to have so important an effect upon the country overlooked by the Rocky Mountains, Montana's isolation is now a thing of the past. Two railroad routes connect it with the East and Pacific West, and there is still the Missouri, navigable from St. Louis to the great Falls, within easy reach of Helena.

The early history of Helena, which fortunately may still be gathered from living witnesses, is a striking illustration of the fact that chance and luck were once the two most important factors of ultimate success in the Territory. None who came into Montana in early days were systematic discoverers. The majority of them knew little of the the theory of mining. What success they had was due to luck. The paying properties they found were nearly all discovered by chance.

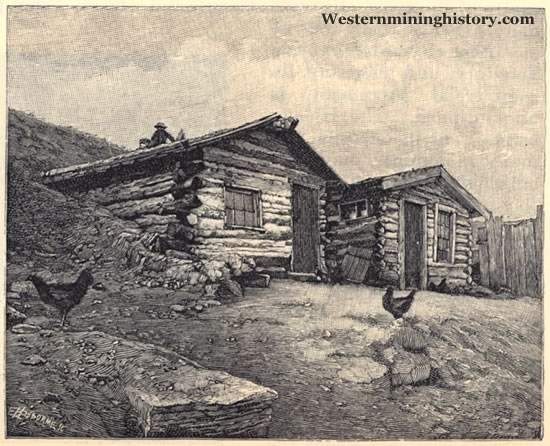

When John Cowan and Robert Stanley grew dissatisfied with the amount of room afforded them in the overcrowded camps of Alder Bulch, they resolved to push northward to Kootanie, where rich diggings had been reported. In July, 1864, the two men and their friends reached a tributary of the Prickly-Pear. There the supply of food they had brought ran low, and further progress northward was impossible. In despair, the party made camp and began to dig for gold. Luckily finding it, they named their diggings the Last Chance Mines, and their district Rattlesnake, the latter word being suggested, no doubt, by the presence of earlier settlers than they themselves. In September Cowan and Stanley built their cabins, and thus had the honor of being the first residents of a camp that in after-years became the present city of Helena.

From the very first, Last Chance Gulch fulfilled it's first promise. Soon after Cowan's cabin was completed a Minnesota wagon train reach the valley, and brought an increase of population to the young camp, the fame of which had gone broadcast over the land. Fabulous stories were told of it's great wealth, and during the winter of 1864-5 there was a wild stampede to it from all the directions. But still the infant Helena was without a name. The first Territorial election had already been held, and on the 12th of December the first Legislature assembled at Bannak. In view of this progress, the miners of Last Chance decided that their camp must no longer go unchristened. At a meeting held in the cabin of Uncle John Somerville the name Helena was accepted, and given without dissent to the collection of rudely built huts in which the miners lived.

Helena then entered upon its eventful and prosperous career. Discovery followed discovery, and the town, unsightly with its main streets occupied by sluice boxes and gravel heaps, became the centre of a mining district that proved richer every day. In the summer of 1865 the first newspaper was printed The press was brought in over the mountains on the backs of pack-mules, and many of the earlier editions were printed on yellow wrapping paper.

In 1869 the township of Helena was entered from the general government. In a period of seven years the placer claims near Helena yielded $20,000,000, and although far removed from the outside work, the city, as a mining centre, was of great importance, and may be said to have enjoyed an uninterrupted period of success.

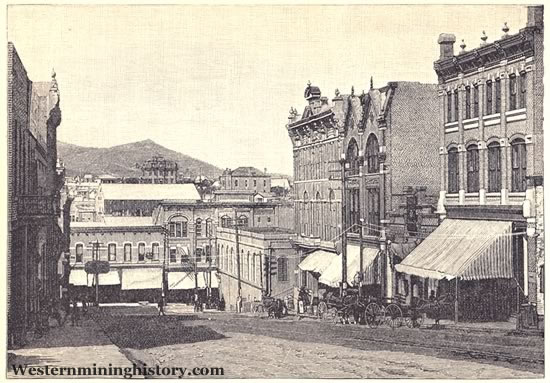

Helena, regarded from a local standpoint, is the geographical, commercial, monetary, political, railroad, and social centre of Montana. Its trade is larger and more extended than that of any other city or town in the Territory, and therefore its commercial supremacy is unquestioned. The Helena banks, rich in deposits and many in number, may well entitle the city to its claim as the monetary centre. The terminus of the lately completed Manitoba system, and having the Northern Pacific as an outlet to the east, west, and south, it has several branch roads to the important mining camps of of Wickes, Marysville, and Rimini, and is promised others which are to aid in developing the rich districts scattered about the surrounding country.

Helena, in the truest sense of the word, is cosmopolitan. Let one walk the streets at any hour of the day or night, and he will be sure to notice the peculiarity. Crowding the sidewalks are miners, picturesque in red shirts and top-boots; longhaired Missourians, waiting, like Micawber, for something to "turn up"; ranch-men, standing besides their heavily loaded wagons; trappers; tourists; men of business. China men and Indians, Germans and Hebrews, whites and blacks, the prosperous and the needy, the representatives of every State in the Union, Englishmen and Irishmen, all make Helena their home. No traditions, no old family influence, no past social eminence, hamper the restless spirit of the busy workers. There is a long list of daily visitors, and the city is never without its sight-seers. Invalids seek it for its climatic advantages.

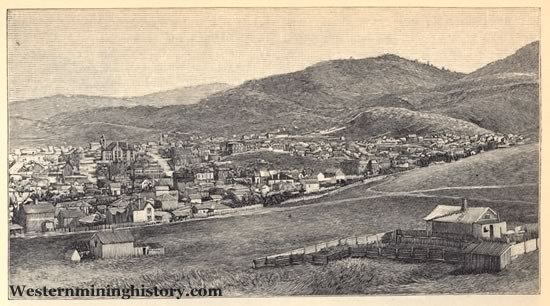

The site of Helena, though the railway station is a mile from the heart of the town, was most happily chosen. It could not have been better had Cowan and his confreres foreseen the future size and importance of the camp they founded. The city faces toward the north. Behind it rise the mountains of the main range, the noble isolated peaks, bare, brown, and of every varying shape and size, forming a background of which one never tires. The old camp was gathered into the narrow quarters of the winding gulch, that extends from the mountains to the open valley of the Prickly-Pear. The present city has outgrown such limitations, and from the gulch, down which the leading business street runs, has spread over the confining hills, and today proudly looks out upon the broad valley and far beyond it, to the peaks that mark the course of the great Missouri.

Directly overshadowing the city is Mount Helena. From it the view is broadest, grandest, most complete. At one's feet is the town of rapid growth. You can see the houses scattered at random over the low, bare elevations, and in the old ravine, the source of so much wealth, the scene of such strange stories, are the flat-roofed business blocks in which Helena takes such justifiable pride. It is no mere frontier town that you look upon. It is a city rather-a city compactly built, and evidently vigorous and growing. On its outskirts, crowning sightly eminences or clinging to the steep hill-sides, are the new houses of those upon whom fortune has smiled, and far out upon the levels are scattered groups of buildings that every day draw nearer toe the railway that has come from the outside word to lend Helena a helping hand.

Leaving the hotel in the very heart of the tow, and following Main Street to its upper end, wee find ourselves in the oldest part of the city. Nothing here is modern or suggestive of wealth. AT your side are rudely built log cabins, with gravel roofs and dingy windows. They are time-stained and weather-beaten now. Chickens scratch upon the roofs; half-fed dogs slink away at your approach. A chinaman has taken this for his home, and has hung his gaudy red sign of Wah Sing over the low doorway; and in this live those who have failed to find in Helena their El Dorado, and now are reduced to living Heaven only knows how. But in years gone past, when the city was a camp, who scoffed at a cabin of logs? These huts were the homes of the future capitalists.

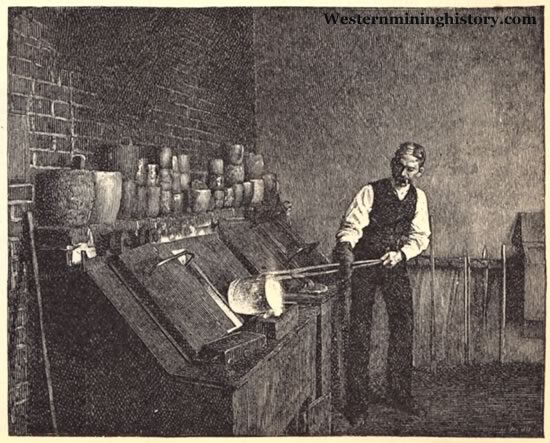

We pass once more into Main Street, and from it onto broadway, that climbs a steep hill-slope, and brings us to the government Assay Office. It is a plain two-storied brick building with stone trimmings, and occupies a little square by itself. Within, all is order and neatness. To the right of the main hall are the rooms where the miners' gold-dust and silver ore are melted and poured in molten streams from the red-hot crucibles. Bars and bricks of the precious metals are shown, and in the vaults they are stacked in glittering array. Every room has its interest. In one the accounts are kept by the assayer; in another are rows of delicate scales, in which the smallest particles of ore are weighed to determine the purity of the moulds packed away in the strongly guarded vaults.

As the ore is received it is tested, weighed, and melted. from the retorts it is run into moulds, which, after being properly valued and marked, are placed in vaults or shipped to the government Mint at Philadelphia. An ordinary gold brick is a trifle larger than the common clay brick. One was shown us which measured 9 inches long, 3 1/2 wide, and 2 1/2 high. Its actual weight was 509 25/100 ounces, the component parts being (basis 1000) 667.2 gold, 294 silver, and 29.2 baser metals. The cash value of the mould was $7,373.

The County Court-house, costing $200,000, is one of the most conspicuous objects of the city. Besides affording accommodation for all the courts and officers of the county, it has rooms for the Governor and other Territorial officials, the Montana Library (both law and miscellaneous), the Historical Society, and the Legislature. The walls are of Montana granite, quarried near Helena, and the trimmings, of red sandstone, came from Bayfield, on Lake Superior. The building is 132 feet long by 80 wide, and with the basement is three stories high.

To the left of the main entrance is a Norman tower. From it is had one of those views for which Helena is so famous-a view of city, valley, mountains. We are nearly 5000 feet above sea-level, and the air is clear and rarefied. Swiftly flows the blood through our veins, and our lungs are all expanded. No wonder the people love their city. Never is the weather sultry, never is the heat oppressive. In winter, a month of snow and terrible cold: then an early spring, with wild flowers in March, and green grasses in April.

From the Court-house our way is through a succession of residence streets. All are wide, long, and straight. On either side grows a row of cotton-wood trees, t he leaves turning now, and some of them dropping to the ground, on this September day. Behind the trees are cottages, some of wood, others of bright red brick: and before and around each house is a bit of lawn, with a few shade trees, and a flower bed tucked away in some sunny corner. Here a riding party is ready for a canter out into the valley or to the mountain trails; and there stands a pony phaeton, upstart successor of the old canvas-covered wagons that twenty years ago were the only vehicles to be seen in this far-off land.

The newer and more pretentious houses in Helena are on Madison Avenue, a wide thoroughfare nearly parallel to Main street, but having a much higher elevation and more commanding outlook. A few years ago the plateau which may now be regarded as the "court end" of Helena was without a tree or house. It now presents an entirely different appearance. Madison Avenue in itself would claim attention in any city, while the residences that face it afford striking evidence of the fact that Helena is fast outgrowing all the provincialism, and to day deserves the encomiums that one is inclined to bestow upon it.

Leaving the cottage-lines streets, we will descend the hill to Main Street once more, and crossing the city, climb to this popular boulevard. Far away, across the valley, are seen the purple peaks of the Beet Range, out of which rises a huge cone known as Bear's Tooth. At it's base the Missouri takes its plunge into the Gate of the mountains. For more than a hundred miles the view is unobstructed. Mountains are everywhere; piled together here; broken, snow-capped, and isolated in other directions. No wonder that the people have selected the plateau as the site of their best houses. In no other city of the far West is there to be had a more extended or a more interesting view.

Benton Avenue is another favorite residence street. Walking down its shaded length, passing the houses that are springing into existence as though by magic, we gain a still deeper insight into the life and attractions of the city. Are we interested in churches? If so, they are here, Episcopal, and Congregationalists, Baptist, Methodist, and Catholic. Scattered at random about the city, and in no instance being more than well suited to present needs, they still give Helena its proper tone, and show by their presence that a new life has crept into the old camp of reckless mining days.

The Helena Board of Trade was organized in 1887, and on the 1st of January, 1888,. issued its first annual report. Many interesting facts regarding the growth of the city are given in the pamphlet. The assessable wealth of Helena in 1887, according to the Secretary of the Board, is $8,000,000, or, estimating the population at 13,000, over the $615 per capita. The assessed valuation of Lewis and Clarke County for 1887 was $11,000,000, while it's actual wealth was $75,000,000. There were 388 new buildings erected in Helena and its several additions in 1886 and '87, the total cost of which was

$2,037,000.

The chief social organization in Helena is the Helena Club. Among its members are men prominent in all business circles, and in such industries as cattle-raising and mining. The club rooms are fully supplied with current literature, and are the popular resort during the late afternoon and early evening. A stranger in Helena is moderately sure of finding whomsoever he wishes to meet at the club, and I am sure the hospitalities of the organization are always gladly extended.

In her schools and other public institutions Helena is fully abreast of the times. There are five brick school-houses in the city, and money for their support is raised by direct taxation on property. School lands cannot be sold in Montana until the Territory becomes a State. Then, however there will be 5,000,000 acres available for the establishment of a fund that will relieve the tax-payers from their present burden.

Besides the public schools there are other institutions, maintained by the Catholic sisters, and a business college with an enrollment already of nearly 500 scholars.

The two library associations of Helena, namely, the City Library and the Historical Society's Library, were both destroyed by fire in 1874, but have since been replaced by collections that are large, varied, and valuable. The Law Library contains nearly 4000 volumes of reports, text-books, and laws. The last Legislature appropriated $3000 to its use. The Historical society's Library consists of original MSS., old historical works, home pamphlets and maps, and contains 5000 volumes. The society occupies two rooms in the Court-house, and last year was given $400 by the Legislature. The object of the officers is to collect and preserve such original letters, diaries, and accounts of travel in Montana and shall serve as the material from which a comprehensive history of the Territory may be gathered. The Helena Free Library contains 2500 carefully selected books of miscellaneous reading, and is supported by a city tax of one-half mill on each dollar of valuation. The income from such source was $2600 in 1886. Still another library is that belonging to the Young Men's Christian Association.

Sufferers from pulmonary troubles are often greatly benefited by living at Helena. The air is dry and bracing, and acts as a tonic to those who have not much natural energy. It would be unwise to advise all who are ill to try living a Helena. No one can select a new home for a patient without first knowing his particular troubles. But I have no doubt that one who takes his case in hand before disease does more than suggest its presence, and goes to Montana prepared to live in the open air, will be able to build up his constitution and begin life anew.

But having seen the city, let us now visit Wickes, and glance for a moment at one of the regions from which the people draw the revenue that they have poured so freely forth for the public good. Making an early start, we will drive down Main Street to the station, and taking the train there, ride down the Prickly-Pear Valley to the Junction, and then on toward the southeast to our destination. On one side ride the mountains, with cool, inviting-looking canons, hemmed in by high hills, and leading into the heart of the range; on the other is the valley, extending far away to hills in the east. Grasses are brown, and the pines deep green. For an hour the Montana of old is ours to enjoy: isolated, quiet, just as nature fashioned it.

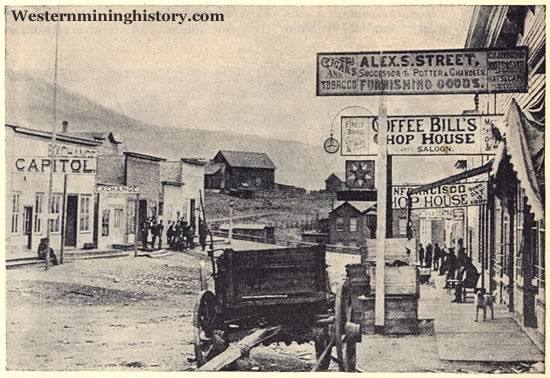

And then comes Wickes: an unsightly town; a mining camp; a place with many saloons and no churches; wooden shanties; wavering streets; groups of men, flannel shirted, unshaven; a background of mountains. This is the picture. We can hear the heavy pounding of the crushers in the works; the air at times is heavy with the smoke of the furnaces. The town is not inviting. It is, as Helena once was, rough, uncouth, repellent almost; but it is rich

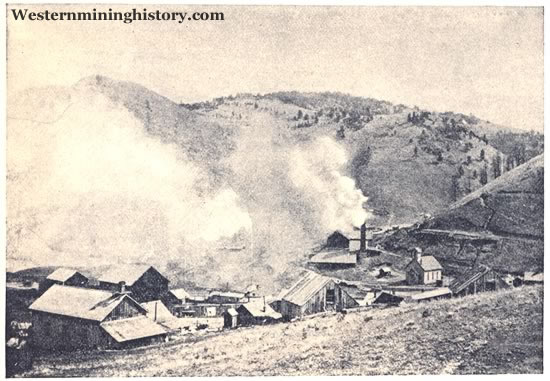

Not rich in itself perhaps, but unquestionably so in its surroundings. The largest so in its surroundings. The largest works at Wickes are those of the Helena Mining and Reduction Company. The town is the creation of this company, and the works bring together the throng that greets us. The product of the smeltery in 1886 had a money value of $1,105,190,76. Nearly 500 men are employed, and ore from Idaho as well as from the mines near the town is treated. Standing anywhere in the main street, we look upon a country fairly riddled with mines. Some of them are famous producers; others are but just opened. One can scarcely realize the possible future of the region. Every day brings in progress; every year the output is greater. As we walk through the dimly lighted buildings, stopping now to watch the crushers and again to listen while the guide explains the process of reduction, one begins to form a just estimate of Helena's claims, for all this district is at her very doors, and the more money Wickes produces, the more brilliant become the prospects of the Territorial capital.

Marysville, nearly thirty miles from Helena, is a second Wickes in appearance, but when one remembers the wealth of the mines which have created the town, he forgets the ugliness of the streets, and ceases to notice the dilapidation of the rudely built cabins. Marysville is chiefly famous as the site of the Drum Lummon, but does not depend on this mine alone for its support. The town is the chief seat of an extremely rich district, already well developed, and is an important suburb of Helena. It is connected by rail with the latter city, and will eventually be the terminus of a branch of the Manitoba road.

The discoverer of the Drum Lummon was Mr. Thomas Cruse. In the days before he sold his property and returned to Helena a much honored millionaire, Mr. Cruse was locally known as "old Tommy," and was looked upon as a somewhat visionary man. None questioned after a time that his mine, where he lived and labored alone, was valuable, but few placed its worth so high as did the patient owner. When he refused half a million for his mine, the people of Helena called him foolish, an when he turned away from the offer of a million, they called him a fool. But the miner was wiser than his friends, and eventually received his price, $11,500,000, and a goodly number of shares in the new company. Then, as so often in the case, the old familiarity was dropped, and the "Tommy" of by-gone days became Mr. Thomas Cruse, "capitalist." A kind, thoroughly honest man, of whom all who know him are ready to say a good word, he is a familiar figure on the streets of Helena, and to-day is president of a savings-bank in he city where a few years ago he was not sure of getting trusted for enough to keep himself alive. As an illustration of the ups and downs of a miner's life he is a notable example.

Mining, fascinating as it seems to one who learns only its brighter side, must not be thought the only industry from which Helena derives it revenue. It is undoubtedly the chief occupation of the people, but fortunes have been made and are now being made in that other great Montana industry, stock-raising. In his last report, the Governor of Montana estimated that there were then in the Territory:

Cattle...............1,400,000

Horses.............. 190,000

Sheep................2,000,000

Sheep-raising is a most profitable business. The Montana grasses are abundant and nutritious, and a vast area of country is available for pasturage. Montana wool has a ready sale in Eastern markets. The clip for 1887 is estimated at 5,771,420 pounds. Cattle suffered severely in the winter of 1886-7, and the industry was badly crippled, although not by any means annihilated. Millions of Helena capital are invested both in sheep and cattle, and it is an open question which have been the more successful, the miners or the stockmen. "Cattle kings," as the men how have made fortunes out of stock are facetiously called, ar by no means a rarity in eh city. The possessions of many of them ar enormous. I doubt if even the men themselves know exactly how many sheep or cattle they own.

Related Articles

Two Montana Cities Part II - Butte

Helena, Montana information and photos