Baldy Mountain District

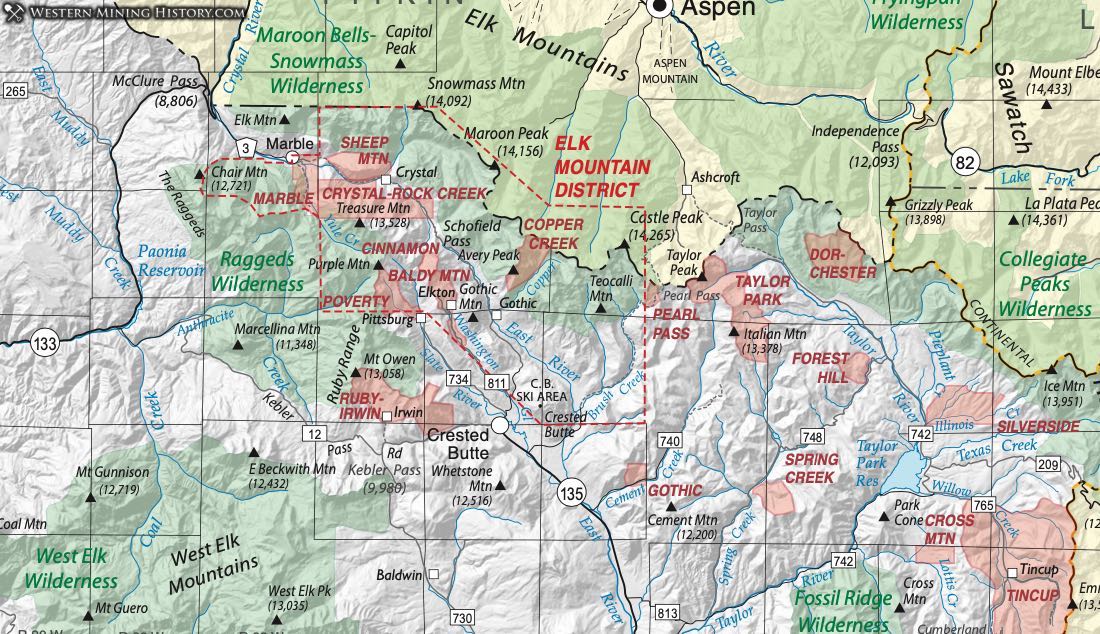

The slopes of Mount Bald and the head of Washington Gulch to the town of Elkton comprise the Baldy Mountain District according to Dunn (2003). It is included within the Elk Mountain District on our map. Very little production is reported. Refer to Elk Mountain District for more detail.

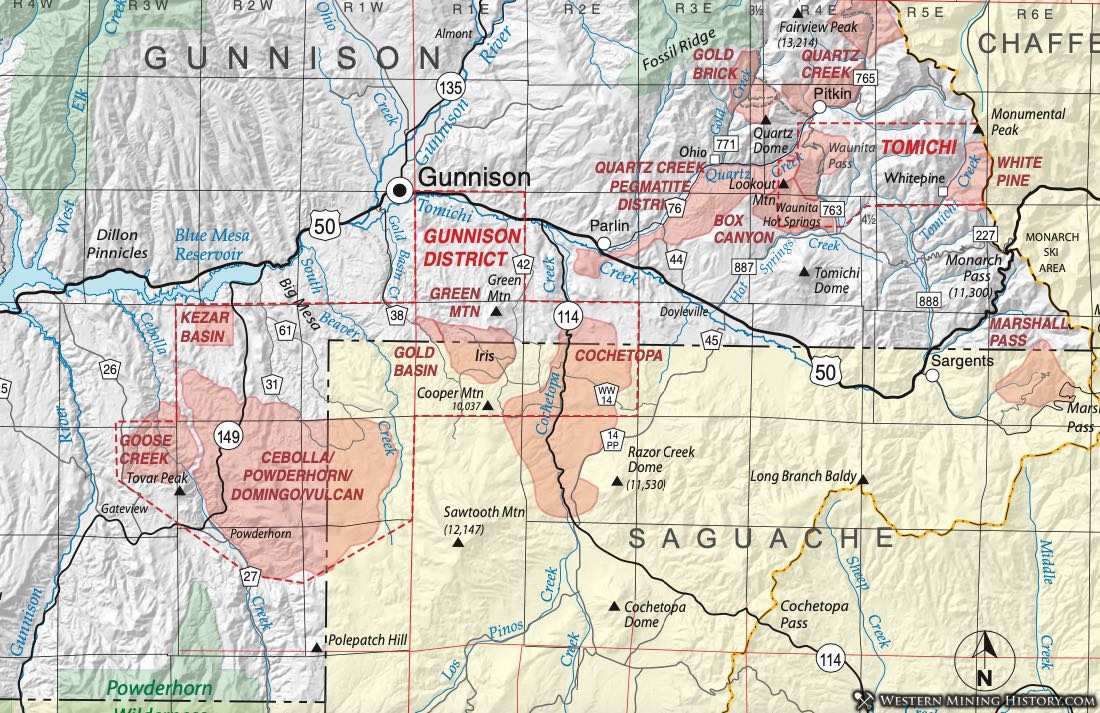

Box Canyon District

As described by Dunn (2003), the Box Canyon District lies bounded by the Quartz Creek District on the North, by Tomichi Creek on the South and on the East by the divide between Tomichi and Hot Spring Creeks. The district is discussed by Hill (1909). Henderson (1926) indicates it may be referred to as the Tomichi District (although these two are represented individually on the CGS map.) Streufert (1999) indicated it was sometimes also known as the Waunita District.

The country rock consist of granite and interlayered felsic and hornblende gneisses and mica schists. Ore deposits are confined to Proterozoic-aged rocks and the major ores were gold and silver (Streufert, 1999). (Refer to the Tomichi District for more detail.)

Vanderwilt (1947) described the Independence and the Camp Bird mines as the main mines in the district, north of Waunita Hot Springs northwest of Sargents. Vanderwilt (Ibid) said that production had been from free-milling small quartz lenses in schist, with significant production for a number of years.

The Independence Mine was mined out by 1909 (Hill, 1909). Production resumed in the 1930s, with 573 tons of ore producing 69 oz of gold and 10 oz of silver in the years 1932, 1938 and 1939 (Vanderwilt, Ibid).

Cebolla District (grouped with Domingo, Powderhorn, Vulcan, and White Earth Districts)

The Cebolla District lies in southern Gunnison County, extending across the border into Saguache County. The districts of this area have been variously combined or considered separately. Henderson (1926) named the Cebolla District specifically, calling it synonymous with the White Earth District. Vanderwilt (1947) uses the Cebolla District as a major heading, but names it as synonymous with the Vulcan, Domingo, and Powderhorn Districts in addition to the White Earth District. Streufert (1999) also provides alternative district names of Vulcan, Domingo, White Earth and Goose Creek. Mindat.org, reflecting the confusing situation, presents a complex listing for the Cebolla District, naming it separately, but also as synonymous with the Vulcan and the Goose Creek Districts.

The district as defined lies mostly in the Rudolph Hill Quadrangle south of the Gunnison Gold Belt (south of the Gunnison District). The geology consists largely of granitic and mafic intrusives of Proterozoic age overlain by Jurassic Morrison Formation and Oligocene ash-flow tuffs (Olson, 1974). Ore deposits are vein deposits associated with the felsic intrusives.

Cinnamon District

Dunn (2003) places the Cinnamon District around Paradise Flat and the upper Slate River valley opposite Cinnamon Mountain. We have enclosed it within the area of the Elk Mountain District. There is no production reported. The district is not listed in mindat.org. An additional reference is Eberhart (1969)

Cochetopa District (aka Cochetopa Creek District; aka Green Mountain District; aka Gold Basin District)

The Cochetopa District lies mainly in Saguache County, but extends into southern Gunnison County along Cochetopa Creek. Henderson (1926) listed the Cochetopa District; later, Vanderwilt also named the district and considered it synonymous with the Gold Basin and Green Mountain Districts. Streufert (1999) in his compilation of data on Gunnison County, also groups those three districts. Afifi (1981) writes about the "Iris District," but it's not clear that he is referring to a mining district, per se, or just the area of the Iris Quadrangle. Mindat.org notes that it is synonymous with the Cochetopa Creek District.

Cross Mountain District

The Cross Mountain District was recognized by Henderson (1926) in his lexicon of mining districts in Colorado. It is described by Dunn (2003) as encompassing the area of and to the east of Cross Mountain, west of the Tincup District in eastern Gunnison County. Streufert (1999) indicates that the district includes the east side of Cross Mountain and upper Lottis Creek. The district was also discussed by Hill (1909).

Hill states that the mines of the Cross Mountain District are mainly on the east side of the ridge running north from Fairview Peak, and some prospects lie east of Lottis Creek. The geology of the mineralized area is composed of sedimentary rocks dipping steeply east. The north-south ridge between Broncho Mountain and Cross Mountain is capped by Lower Paleozoic sediments as erosional remnants in Precambrian granite. These are interpreted by Zech (1988) to represent the remnants of a thrust plate.

Vein and replacement deposits in the Paleozoic rocks appear to be associated with small sills and stocks of Laramide-age andesite porphyry. Hill (Ibid) describes the ore as primarily argentiferous galena.

Goddard (1936), in his paper on the Tincup District, describes the Wahl Mine, on the summit of Cross Mountain, as a replacement in the Ordovician Fremont Limestone. Small, flat lenticular zones of Fe and Cu-Fe sulfides in a quartz-calcite gangue occur as zones 3-6 feet wide and 10-15 feet long. Gold, copper, and manganese were produced from the Wahl Lode (DeWitt et al., 1985). (The Wahl Mine is listed on mindat.org as occurring in the Tincup District.)

Goddard (Ibid) also describes the Gold Bug Mine as a fissure vein cutting lower Paleozoic sediments with irregular masses of chalcopyrite in quartz. Gold, silver and lead have been produced from this mine (DeWitt et al., 1985) and copper (Streufert, 1999). (The Gold Bug Mine is also listed in mindat.org as being in the Tincup District.)

Crystal River District (aka Rock Creek District; aka Crystal District)

The Crystal River District was listed by Henderson (1926) as synonymous with the Rock Creek District. The original name was the Rock Creek District and was stablished by 1883, but the Crystal River District name was established by the late 1940’s (Dunn, 2003). Dunn (Ibid) describes the district as the area around Eureka, Meadow and Galena mountains and Crystal Basin. The district is contiguous with and overlaps the Sheep Mountain District and will be considered in the same discussion.

Vanderwilt (1937) attributes the first discoveries in the area to the early 1870s. The first ore shipments came from the Eureka Mine on Treasury Mountain prior to 1876, then the Black Queen, followed by the North Pole and Lead King in 1900. The greatest production came from the Lead King (lead-zinc with some silver), followed by the Black Queen (silver) and the North Pole (copper-gold).

Ore deposits in the area are concentrated on the northeast side of the Treasure Mountain Dome in a zone of faulting from Sheep Mountain on the northwest to Galena Mountain on the Southeast - a zone eight miles long and one to three miles wide. Deposits include both mineralized veins and bedded replacements. Vanderwilt (Ibid) interpreted them as being associated with the granite porphyry of Treasure Mountain, a Miocene intrusion (Mutschler et al., 1981).

Vanderwilt (Ibid) related an interesting story. While early prospectors concentrated on conspicuous quartz veins, the best deposits ended up coming from the replacement deposits which were connected to their sources by small, inconspicuous conduits.

Streufert (1999) enumerated mineralization in several environments. One was upper Paleozoic to Cretaceous rocks in the Treasure Mountain Dome. A second is from Cretaceous quartzites on the flank of the Dome near Mineral Point. To the north are metamorphosed Cretaceous rocks at the edge of the Middle Tertiary granodiorite stock (Snowmass Pluton).

The 1937 Vanderwilt paper contains many excellent descriptions of individual mines (as noted in the mine list below.)

The short lived camp/town of Holland was established west of Marble when low grade ores were discovered in the 1880’s (Dunn, 2003). The camp of Crystal City was established in the early 1880’s and housed the Crystal Mill. Residents of Crystal City worked the Black Queen and Lead Queen Mines, and the Sheep Mountain Tunnel (Dunn, Ibid). The district also included Marble (incorporated in 1899) and the Marble railroad station. The camps of Rock Creek and Galena are probably included in the district (Dunn, Ibid). Marble is named for the Yule Marble, Colorado’s state stone, used in creation of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and the Lincoln Memorial, as well as other buildings.

Dorchester District (aka Taylor River District; aka Taylor Peak District)

The Dorchester District lies in northern Gunnison County near the Pitkin (and Chaffee) County lines (Dunn, 2003). Vanderwilt (1947) discussed the district, but considered it to be synonymous with the Taylor River District (and the Tincup District.) Henderson (1926) did not recognize the Dorchester District, but did list the Taylor River District, which he considered synonymous with the Tincup, Taylor Park and Forest Hill Districts, further complicating the nomenclature and location of all these districts. Streufert (1999) referred to it as the Taylor Park District.

Harder (1908) discussed iron ore deposits in the Taylor Peak District, which appears to cover the same territory as the Taylor River District. The Taylor Peak District is also enumerated on the website www.mindat.org. It appears to be largely placer mines. Eberhart (1969), discussing the early mining camps, considered this area a part of the Forest Hill District. The reader must recognize the confusion accompanying their location and nomenclature.

Regarding Dorchester, Dunn (Ibid) recounts that mining went on early, but not much is known other than that deserted cabins were found already in 1873, obviously indicating earlier habitation. Some significant deposits appear to have been part of this polymetallic mineralized district, including the Clara, the Ender, the Bull Domingo, the Hope, and the Star.

Geologically, Paleozoic sediments overlie Precambrian granitic rocks, which are intruded by the Middle Tertiary White Rock Pluton, a tonalite body (Streufert, 1999). Not much geologic detail is known about this area.

Elk Mountain District (includes Sheep Mountain, Gothic, Crystal River/Rock Creek, Marble, Cinnamon, Copper Creek, Baldy Mountain, and Poverty Districts)

The Elk Mountain District was included by Henderson (1926) in his comprehensive list of Colorado mining districts. Dunn (2003) describes the district as comprising "much of the area near the border of Gunnison and Pitkin Counties." Hill (1912) called this the Ruby District, but we exclude that district south of the Elk Mountain. On our map, we enclose the Sheep Mountain, Crystal River (or Crystal)/Rock Creek, Marble, Cinnamon, Copper Creek Baldy Mountain, and Poverty Districts within the Elk Mountain.

The Elk Mountain District also includes mineral resource locations that fall outside of these individual smaller districts. As a result, this description will summarize those smaller districts, but some information can be found in most of those individually.

Dunn (Ibid) states that the district existed and was active by 1880 and gradually expanded its boundaries to include the neighboring districts.

In the mineralized areas, Paleozoic and Cretaceous sediments are intruded by Tertiary igneous bodies - notably the Oligocene-age White Rock Pluton. Most of the production came from the upper Paleozoic clastics and carbonates.

Vanderwilt's (1947) general description notes veins with sphalerite, galena and chalcopyrite with some silver and gold content. Mineralization is widespread, but veins are generally small and irregular. Streufert (1999) and Gaskill et al. (1991) delineate three types of deposits within the Elk Mountain district: 1) Ag-Au -Pb-Cu-Zn veins in metasediments (with some skarn zones); 2) Ag ores in masses of pyritized rock in metasediments and rhyolite porphyry dikes; 3) contact metamorphic deposits of massive magnetite and iron sulfide, Fe-Cu sulfide and gold. Significant molybdenum mineralization occurs within the area.

Most famous within the district is the Yule Marble quarry at the west end of the district near the town of Marble. There, the Leadville Limestone has been metamorphosed into a beautiful marble, including some of the most pure white product known. Through the years, Yule Marble has been used for the Lincoln Memorial, the Tomb of the Unknowns, municipal buildings in New York, San Francisco and Denver and numerous other structures around the country (Eberhart, 1979).

Vanderwilt (1947) reported production during the period 1932-1945 coming from four lode mines and three placer mines at 188 oz. gold, 15,000 oz. silver, 18,700 lb. copper (in 1939), 36,000 lb. lead, and 10,000 lb. zinc.

A number of small towns grew up, their history chronicling the history of mining in District. Marble developed after the pure white marble was discovered in 1882, with some small gold and silver prospects also in the area. Crystal was the site of rich silver strikes in the 1880s in the Crystal/Rock Creek District. Elko was a short-lived town at the foot of Galena Mountain and Schofield grew up at the base of Schofield Pass - the earliest access road to the region.

The biggest and most famous town was Gothic. Rich gold and silver strikes at Gothic Mountain in June 1879 gave rise to a town that reached a population of 8,000 citizens at its peak (WMH note - this figure seems unlikely). Eberhart (Ibid) describes the most significant mine in the Gothic area as the Silver Night Mine on Copper Creek, where rich pockets of silver (native and wire) assayed as much as 6,000 to 15,000 ounces per ton silver. The largest producer in the area of Gothic was the Sylvanite Mine, described by Gaskill et al. (1991) as containing 2,200 feet of tunnels, 1200 feet of vertical workings and extensively stoped areas.

Forest Hill District

The Forest Hill District is probably best considered part of the Taylor Park District. Henderson (1926) listed the Forest Hill District. Dunn (2003) notes that it may overlap with the Dorchester District to the North, but we show them separated by the Taylor River, several miles apart. Lying in the Italian Creek Quadrangle, the Forest Hill has only one notable mine - the Forest Hill Mine.

Fridrich et al. (1998) show the area underlain by Oligocene-age andesitic tuffs, flows, and breccias. The Forest Hill mine apparently lies at the contact of the volcanic rocks with Proterozoic rocks south of the Grizzly Peak Caldera.

Gold Basin District (aka Iris District)

The Gold Basin District lies at the northeast end of the Gunnison Gold Belt (refer to the Gunnison District). The district is located in the Iris and Iris NW 7.5-minute quadrangles, either within or adjacent to four other mining districts on the border of Gunnison and Saguache Counties: the Gunnison, the Green Mountain, the Iris and the Cochetopa. To further confuse the situation, the term Cochetopa Creek District has also been used (mindat.org, July 2015). Here we attempt to make some distinctions on the identity and location of these districts.

Henderson (1926) stated that the Gold Basin District adjoined the Green Mountain District and then stated that the Green Mountain was synonymous with Cochetopa District in both Gunnison and Saguache Counties. Dunn (2003) followed that example. Mindat.org equates the Green Mountain and the Gold Basin Districts in Gunnison County. Vanderwilt (1947) considered the Green Mountain, the Gold Basin and the Cochetopa the same, and does not mention the latter in his Saguache County section.

Afifi (1981), Drobeck (1981), and Sheridan et al. (1981) wrote about the general area of the Gunnison Gold Belt, but only Afifi mentioned any specific mining district, and he called this area the Iris District in the Iris and Iris NW quadrangles. Streufert (1999), in grouping districts by dominant deposit type, includes the Green Mountain District and the Gold Basin District as "mining areas" within the Cochetopa District, characterized by stratabound sulfide mineralization. Cappa and Wallace (2007) also use the name Iris District in northern Saguache County within the Gunnison Gold Belt.

The most informative description comes from Hill (1908). He described the districts this way: "There are two districts south of Tomichi Creek, the Gold Basin and the Cochetopa, within which a small area around Iris and Chance has been set aside as a separate mining district called Green Mountain." Because Hill provides this specific description originating at the time the districts were active, we have used this.

The geology and mineralization of the Green Mountain District is typical of the Gunnison Gold Belt (refer to the Gunnison District.) The mines in the area that have been specifically discussed include the Denver City and the Yukon (or Yukon-Alaska). Mindat.org lists the Denver City in the Green Mountain/Gold Basin District (it is located at the townsite of Iris) and the Alaska-Yukon in the Cochetopa District (this mine is located east of Cochetopa Creek at the far eastern boundary of the Gunnison Gold Belt). Hill (Ibid) provides detail on the Lucky Strike Mine (in Gunnison County near the town site of Chance).

Eberhart (1969) discussed the twin mining towns of Chance and Iris on opposite sides of the Gunnison - Saguache County line. Both founded in 1894, both towns saw a population of around 1,000 in their short heyday. Also, both towns faded in 1897, enjoyed a brief revival in 1901-1902, but died out again.

Gold Brick District

Henderson (1926) recognized the Gold Brick District in his compilation of Colorado mining districts. Hill (1908) had visited the district twenty years earlier and listed also the district in his 1912 compilation. Vanderwilt (1947) described the district as being characterized by small, but rich, veins that result in small tonnages of relatively rich ore. Most of the deposits are shallow. Zech (1988) possibly provided an explanation for the shallow deposits when he interpreted the district as sitting on a thrust plate transported from the east.

Streufert (1999) described the district as sitting along Gold Creek north of the confluence of Quartz Creek at Ohio City. He summarizes the numerous earlier works, providing a good description of the geology of the area. Most of the deposits occur in veins in Proterozoic rocks - both metavolcanics and granitic rocks. Some contact metamorphic deposits of iron and iron-sulfide occur.

The northwest part of the district has somewhat of a different geology. Fossil Ridge contains a sequence of Paleozoic sediments. There are some smaller replacement type deposits in Paleozoic carbonates. Heyl (1964) found oxidized zinc deposits in the northwest part of the district. Also, Worcester (1919) describes a number of molybdenum prospects in the area of Lamphier Lakes, on the edge of the district to the north. DeWitt et al. (1985) summarize the more recent geologic studies and interpretations in their study of the mineral resource potential of the proposed Fossil Ridge Wilderness Area, which now includes the northern end of the Gold Brick District. They point out that there are areas in and around the Gold Brick District that have high potential for gold and silver in veins and shear zones.

Crawford and Worcester (1916) and Parker (1974) have brief mention of gold placers in the Gold Brick District including Jones Gulch, Dutch Flats, and Spring Gulch.

Eberhart (1969), in his description of the town of Ohio City, relates that gold was first discovered in the 1860s but the area didn't grow until silver was discovered in the 1880s (1879 by Dunn, 2003) The Carter and the Raymond were the biggest mines in the district, while the Calumet, the Eagle, and the Roller were right within the "city."

The district became inactive by 1900, but produced again in the period 1934-42. Vanderwilt (Ibid) reported the following production in those years of 16,395 oz. gold; 45,650 oz. silver; 219,000 lb. lead, and 2,350 lb. copper.

Goose Creek District

The Goose Creek District is in the Gateview quadrangle on the western end of the Gunnison Gold Belt (the Gunnison District of this compilation). The district was recognized by Henderson (1926) and Vanderwilt (1947). Vanderwilt referred to it also as the Madera District for the town of Madera on the Lake Fork of the Gunnison River. Mindat.org (2015) includes much of the area to the east within the Goose Creek District.

The Goose Creek District is therefore considered to be a subdistrict of the Gunnison District, with deposits typical of that geology. For details of the Gunnison District mineralization and geology, refer to Drobek (1981), Hedlund and Olson (1975, 1981), Olson and Hedlund (1973) and Sheridan et al. (1981). Here, we consider the thorium deposits to constitute the Powderhorn District, so the Powderhorn and the Goose Creek Districts overlap.

Gothic District

One of numerous small districts within the Elk Mountain District of northern Gunnison County, the Gothic was placed by Henderson (1926) and Dunn (2003) in sections 13, 14, 23 and 24 of T14S, R85W. Streufert (1999) also includes the area of the Gothic District within his description of the Elk Mountain District. Mindat.org does not list the Gothic District, but does list the Elk Mountain District.

Information on the Sylvanite Mine (Silver Knight?) in Gaskill et al. (1991) provides some insight into the mineralization in the district. Near-vertical fissure veins cut metasedimentary rocks and granodiorite. The veins contain native (wire) silver, ruby silver (proustite/pyrargyite), argentiferous tetrahedrite, chalcopyrite, arsenopyrite, barite, massive sulfides, minor gold, and galena. They quote the estimated production of 100,000 to 300,000 ounces of silver.

Eberhart (1969) provides a significant description of the town of Gothic and its history. The biggest and most famous town in the district and area was Gothic. Rich gold and silver strikes at Gothic Mountain in June 1879 gave rise to a town that reached a population of 8,000 citizens at its peak. Eberhart (Ibid) describes the most significant mine in the Gothic area as the Silver Night Mine on Copper Creek, where rich pockets of silver (native and wire) assayed as much as 6,000 to 15,000 ounces per ton silver. The largest producer in the area of Gothic was the Sylvanite Mine, described by Gaskill et al. (Ibid) as containing 2,200 feet of tunnels, 1200 feet of vertical workings and extensively stoped areas.

Green Mountain District

The Green Mountain District lies at the northeast end of the Gunnison Gold Belt (Gunnison District). The district is located in the Iris and Iris NW 7.5-minute quadrangles, either within or adjacent to four other mining districts lies on the border of Gunnison and Saguache Counties: the Gunnison, the Gold Basin, the Iris and the Cochetopa. To further confuse the situation, the term Cochetopa Creek District has also been used (mindat.org, July 2015). Here we attempt to make some distinctions on the identity and location of these districts.

Henderson (1926) and Dunn (2003) have considered the Green Mountain District synonymous with Cochetopa District in both Gunnison and Saguache Counties. Mindat.org equates the Green Mountain and the Gold Basin Districts in Gunnison County. Vanderwilt (1947) considered the Green Mountain, the Gold Basin and the Cochetopa the same, and does not mention the latter in his Saguache County section.

Afifi (1981), Drobeck (1981), and Sheridan et al. (1981) wrote about the general area of the Gunnison Gold Belt, but only Afifi mentioned any specific mining district, and he called this area the Iris District in the Iris and Iris NW quadrangles. Streufert (1999), in grouping districts by dominant deposit type, includes the Green Mountain District and the Gold Basin District as "mining areas" within the Cochetopa District, characterized by stratabound sulfide mineralization. Cappa and Wallace (2007) also use the name Iris District in northern Saguache County within the Gunnison Gold Belt. An additional reference is Hedlund (1981).

The most informative description comes from Hill (1908). He described the districts this way: "There are two districts south of Tomichi Creek, the Gold Basin and the Cochetopa, within which a small area around Iris and Chance has been set aside as a separate mining district called Green Mountain." Because Hill provides this specific description originating at the time the districts were active, we have used this.

The geology and mineralization of the Green Mountain District is typical of the Gunnison Gold Belt (Gunnison District). The mines in the area that have been specifically discussed include the Denver City and the Yukon (or Yukon-Alaska). Mindat.org lists the Denver City in the Green Mountain/Gold Basin District (it is located at the townsite of Iris) and the Alaska-Yukon in the Cochetopa District (this mine is located east of Cochetopa Creek at the far eastern boundary of the Gunnison Gold Belt). Hill (Ibid) provides detail on the Lucky Strike Mine (in Gunnison County near the townsite of Chance).

Gunnison District

A profusion of historic districts render southern Gunnison County a confusing area to decipher. The following is a list of fourteen districts associated with this part of the county:

- Gunnison

- Gold Basin

- Green Mountain

- Iris

- Cochetopa

- Cochetopa Creek

- Cebolla

- Domingo

- Vulcan

- White Earth

- Powderhorn

- Kezar Basin

- Goose Creek

- Willow Creek

Very little consistency is found in the use and description of these districts, so we will try to define them in a way that will be useful to students of mining in Colorado. We will try to point out the various definitions and descriptions used by earlier writers, but recognize there is no right or wrong, either with this report or any of the others that preceded it. Because of this, the assignment of specific mines to one district or another is different from one source to another.

For our purposes, most of the area of southern Gunnison County is considered the Gunnison District. These other districts all within the geographical boundaries of the Gunnison District and, in that way, can be considered "sub-districts."

Of those 14 districts, most occur within the metavolcanic-metasedimentary terrain characteristic of the Gunnison Gold Belt. The Powderhorn District is selected out to include the later (Late Precambrian - Cambrian) alkaline intrusions associated with the Powderhorn Carbonatite. The Vulcan District is listed separately because it is a famous and somewhat iconic district in a unique geologic setting even within the Dubois Greenstone.

The Gunnison District is defined to outline the area underlain by the Precambrian terrain known as the Dubois Greenstone Belt (Drobek, 1981; Sheridan et al., 1981; Hedlund and Olson, 1981). As a mining area, this terrain has been referred to as the Gunnison Gold Belt as long ago as 1896 (Lakes, 1896.) The Dubois Belt trends northeast from the Lake Fork of the Gunnison River for some 50 km and is 10 km or more wide, southeast of the town of Gunnison.

The rocks are attributed to submarine fumarolic activity by Drobek (Ibid) who described four major rock types "of interest":

1) metamorphosed arkose, siltite and graywacke;

2) metamorphosed water-lain volcanic flows of basalt to andesite in composition;

3) metamorphosed felsic tuffs, pyroturbidites and flows of dacite to rhyolite in composition;

and

4) syn-to late-tectonic granite, granodiorite and diorite.

Sheridan et al. (Ibid) also point out abundant magnetite-bearing quartzite, probably representing seafloor chert beds.

Hedlund and Olson (Ibid) describe the zone as bounded by the Cimarron Fault on the south, where upper Cretaceous Mancos Shale is displaced against the Precambrian rocks. On the north, the Precambrian rocks dip under the Jurassic and upper Cretaceous sediments.

The style of mineralization is predominantly low-sulfide gold with subsidiary silver. Some lead, zinc, and copper were mined. Specific descriptions of mines and mineralization will be found under the individual districts.

Iris District

The Iris District is an alternate name used for a mining area at the northeast end of the Gunnison Gold Belt. Refer to the Gold Basin District, Green Mountain District, and Gunnison District.

Kezar Basin District

Henderson (1926) and Dunn (2003) list the Kezar Basin District as occupying four sections in southern Gunnison County near the Blue Mesa Reservoir (sections 4, 5, 8, and 9 of T49N, R2W). This area appears to be very close to what Streufert (1999) calls the "White Earth Tungsten Area." No details are available except that Streufert describes scheelite at the Lily Belle Mine.

Poverty District

Dunn (2003) assigns the Poverty District to the area of Poverty Gulch between the towns of Ruby and Gothic. We have included it within the Elk Mountain District. The district spawned the town of Pittsburg, for which Eberhart (1969) has provided a significant narrative. The Augusta Mine was the major producer, with (according to mindat.org) ruby silver ore and tetrahedrite.

Refer to the Elk Mountain District.

Powderhorn District (aka White Earth District)

The Powderhorn District is a unique area in southern Gunnison County. The mining district has variously been considered to be synonymous with the White Earth, Cebolla, Vulcan, and Domingo Districts (Vanderwilt, 1947). Henderson (1926) did not list the Powderhorn, but considered the White Earth District the same as the Cebolla District. Mindat.org also lists the White Earth and the Powderhorn as the same district. Dunn (2003) considers the Powderhorn to be part of the larger Cebolla District.

Streufert (1999), in his survey of Gunnison County mining districts, considered the Powderhorn District to cover "a large area in the southern portion of Gunnison County," much larger than we have considered it here. The central geologic and topographic feature of the Powderhorn District is Iron Hill. Iron Hill consists of a carbonatite stock with numerous carbonatite dikes, pyroxenite and syenite intrusions in the surrounding area. For this reason, we are considering the Powderhorn District to encompass the area in which these uncommon rocks occur.

The best geographic definition of the Powderhorn District is found in Olson and Hedlund (1981), who outline the area that includes the thorium-bearing veins in the Powderhorn, Rudolph Hill, and Gateview Quadrangles, compiled from the geologic maps of those quadrangles (Hedlund and Olson, 1975; Olson, 1974; and Olson and Hedlund, 1973 respectively). Thus, the Powderhorn District overlaps other districts, but is defined exclusively on the thorium-bearing rocks.

Hunter (1925) first noted in southern Gunnison County "an area of highly sodic and nephelinitoid rock, ranging from soda to cancrinite syenite, ijolite and nepheline gabbro to pyroxenite with many curious apatite, analcite and melilite rocks." He also described the carbonate rocks, calling it as many early workers, limestone and postulating a sedimentary origin. He considered the entire complex as Precambrian.

Larsen (1942) revisited the complex and described in detail the unusual rocks. He suggested the possibility that the marble was of igneous origin. He also was not certain of the age, pointing out that the rocks of the complex clearly intruded known Precambrian rocks and were overlain by know Jurassic-age strata.

Following up on a survey by Burbank and Pierson (1953), Olson and Wallace (1956) referred to "pre- Jurassic metamorphic and igneous rocks" of the district. They took special note of the thorium-bearing rocks, which had been the object of prospecting for a number of years - mostly contained, they said, in thorite and thorogummite. They also mentioned the rare earth-bearing apatite and provided a detailed description and discussion of the Little Johnnie Claims.

In a brief description, Hedlund and Olson (1961) were the first to refer to the rocks as carbonatite. They distinguished four rock types with higher radioactivity signatures: carbonatite dikes, magnetite-ilmenite- perovskite bodies, thorite veins and trachyte porphyry dikes. The thorium in the richest areas - the carbonatite dikes - was contained in monazite. Rare earths were described as occurring in baestnesite and synchisite.

Staatz et al. (1979) considered the thorium-rich dikes as a potential thorium resource as well as the major Iron Hill stock, although the latter is also rich in niobium and rare earth elements (REE). In a follow-up report, Staatz et al. (1980) and Armbrustmacher (1980) calculated the resource for ThO2, RE oxides, Nb2O5 and U3O8 from the stock itself.

Olson and Hedlund (1981) summarized the geographic distribution of rocks enriched in thorium and thus provided a good outline of the Powderhorn District as this report defines it, compiled from the quadrangle mapping noted above.

In the twenty-first century, considerable interest in "strategic minerals," led to more investigations of the Powderhorn District and the Iron Hill complex for information on REE, thorium, niobium, and titanium. Van Gosen (2009) provided a history of exploration at Iron Mountain, and reported an estimate of reserves from Teck Corporation suggesting their White Earth property along (within the Powderhorn District) contains 41.8 million metric tons of mineable reserves grading 13.2% TiO2. The titanium is present in perovskite, lucoxene, ilmenite, and titanite. This was noted by Thompson (1987) as the largest known titanium resource in the United States. Van Gosen et al. (2009) and Long et al. (2010) also summarized the resource estimates for those commodities in the Powderhorn District. An additional reference is Del Rio (1960).

Quartz Creek Pegmatite District

In this compilation, we treat the Quartz Creek Pegmatite District as separate from the adjacent districts known for their metallic minerals (Box Canyon, Gold Brick, Tomichi, and Quartz Creek) because of the unique geology. Dunn (2003) described the Quartz Creek Pegmatite District as lying in Townships 49 to 51N and Ranges 3-5 East along the west slope of the Sawatch Range.

Sources differ in their estimate of the size of the district. Del Rio (1960) followed Hanley et al. (1950) in describing the district as occupying ten square miles. Staatz and Trites (1955) claimed 29 square miles, a figure we find more accurate.

Staatz and Trites (Ibid) describe in detail the geology of the district. Rocks range from Precambrian (quartzites, hornblende gneiss, tonalite and dacitic pillow lavas), overlain by Jurassic Morrison formation and Cretaceous Dakota formation. At the north end of the district is a quartz monzonite porphyry. Intruded into the older rocks are a coarse-grained granite and fine-grained granite dikes and pegmatites.

Martin (1993) describes two general forms of pegmatite - long, narrow NE-trending dikes and large irregular masses with no apparent linear orientation. Both types intrude the host rocks unconformably. He describes them as "typical granite pegmatites" but varying from other Colorado pegmatites in that they carry relatively low muscovite, biotite, and tourmaline and relatively high accessories lepidolite, topaz, and microlite.

Del Rio (Ibid) reports that, of the 1803 pegmatites investigated in the district, 232 contain beryl, 14% are zoned and many are lithium-rich (hence the lepidolite). The pegmatite bodies are dominated by albite, perthite, and quartz. Economic minerals include beryl, lepidolite, microlite, topaz, and feldspar; major accessories include beryl, muscovite, garnet, magnetite and biotite. Columbite-tantalite occurs in 29 different pegmatite bodies (with the Brown Derby containing 1.4%); lepidolite in 17% but ranges up to 95% by volume. Monazite occurs in 24 of the pegmatites.

Martin investigated several of the pegmatites for the Bureau of Mines specifically for columbium- tantalum potential. He reported the major producers in the district were the Brown Derby (lepidolite, beryl, microlite - Ta bearing); the White Spar (feldspar and lepidolite) and the Bucky (mica, beryl, monazite and columbite-tantalite).

The mineralization was not discovered until 1930, with the Brown Derby pegmatite. Production did not begin until the war years, specifically 1943, with lepidolite and beryl.

Quartz Creek District (aka Quartz District)

The Quartz Creek District was recognized by Henderson (1926), who described the area as overlapping both the Tin Cup and the Gold Brick Districts. Vanderwilt (1947) describes the district as 1-4 miles northeast of Pitkin near the road to Tincup. Dunn (2003) provides a more specific location description: bounded on the north by the ridge between Fairview Peak and the Continental Divide, on the east by the main range, on the south by Quartz Creek and on the west by the divide between Armstrong Gulch and Ohio Creek. She notes it has also been called the Quartz District.

Vanderwilt (Ibid) describes the district as the southern extension of the mineralized district that includes the Tincup District. Geology is Proterozoic granite and schist in a wide faulted zone extending north to Aspen. Paleozoic sediments and Tertiary intrusives (quartz monzonite porphyry) characterize the area. Veins of silver, lead and gold and replacement deposits with argentiferous galena, tetrahedrite-tennantite in carbonate beds comprise the mineralization along with some molybdenum-bearing quartz veins. Hill (1909) described the mineralization in Armstrong Gulch north of Pitkin. Streufert (1999) describes in detail the Fairview Mine on the divide between Armstrong and Hall Gulches.

Heyl (1964) notes that smithsonite is a common constituent in oxidized ores in the Leadville Limestone in the Maid of Athens Mine. Dings and Robinson (1957) discuss a number of mines in the district, as noted on the list below. They also describe graphite production from Graphite Basin as occurring in the Quartz Creek District. Worcester (1919) discusses molybdenite occurrences in the "Quartz District."

Ruby (Irwin) District

The Ruby District is listed in Henderson (1926). Dunn (2003) describes the district as occurring in the west part of the Elk Range near Crested Butte. The Irwin District has been used as an alternate name and the name Ruby Camp District has been used.

Streufert (1999) describes the district as including deposits in the Ruby Range near Lake Irwin. Mindat.org (2015) extends the district to the east nearly to Crested Butte where it includes the large Mount Emmons molybdenum deposit (Dowsett et al., 1981), a definition that we use here. Vanderwilt (1947) describes the Ruby Mine, 10 miles northwest of Crested Butte, as the signature mine of the district.

The detailed geology has been described by Gaskill et al. (1967, 1987), Gaskill (1986), and Mutschler et al. (1981). Cretaceous and Tertiary sedimentary and igneous rocks are intruded by Middle and Late Tertiary igneous bodies, mostly granites and granodiorites. Veins containing zinc, lead, silver, copper, molybdenum and gold - mostly disseminated - are distributed through the rocks. Ruby silver deposits (proustite/pyrargite), from which the district and the mountains derived their name, were mined for a short period, mainly around 1880 and 1890.

Several towns and mining camps prospered for a short time in the area of the Ruby District. Crested Butte started as a gold camp but prospered later as a coal-mining town, starting in the late 1870s. The railroad and the Pearl Pass road to Aspen solidified the town's standing by 1882 (Eberhart, 1969). Colorado Fuel and Iron (CF&I) ran several of the coal mines (three bituminous coal and three anthracite coal mines), constructing some 150 coke ovens. The mines operated until 1952, at which time work started on a facility to refine lead and zinc ore.

The nearby town of Irwin reached its zenith in 1882 with a mile-long Main Street. Among visitors were General Ulysses S. Grant, Theodore Roosevelt, Wild Bill Hickock and the Vaudeville King of the day Bill Nuttal (Eberhart, Ibid.). The town of Ruby prospered for a few years, as did Haverly and Silver Gate, which were probably just absorbed by Irwin (Eberhart, Ibid.)

Sheep Mountain District

Refer to Rock Creek District.

Silverside District

The distribution of districts in the northeast is confusing at best. Various writers through time have used many names, often interchangeably, for the region stretching from Tincup on the east to Pearl Pass, some twenty miles to the northwest. (Refer to explanations in the Taylor Park, Taylor Peak, Taylor River, Dorchester District descriptions.) The Silverside District seems to occupy an area not claimed by any of the other districts, and it does encompass, among other things, some known gold placer terrain. Therefore, we have chosen to include the district even though the name has not been widely used.

Henderson (1926) first recognized the Silverside District, and it was included in Dunn (2003), encompassing four sections to the northeast of the present-day Taylor Park Reservoir. Parker (1974) listed placer sites of local importance on Texas, Illinois, and Pieplant Creeks. Davis and Streufert (1990) included these placer areas within the Taylor Park District, but here we consider them the Silverside District.

Spring Creek District (aka Spring Gulch District)

Henderson recognized the Spring Creek District in his 1926 compilation and placed it in sections 23-26 of T14S, R83W. Vanderwilt (1947) notes it occurs in a narrow canyon adjoining the Taylor River. Eberhart (1969) mentions Petersburg, the main town in the Spring Creek District. Streufert (1999) describes the area as being characterized by highly-faulted Paleozoic sedimentary rocks (most important of which are the carbonates) and Proterozoic granitic rocks. Mineralization is deeply-oxidized replacement deposits in the Mississippian Leadville limestone.

Heyl (1964) describes the Doctor Mine as the only significant mine in the district. The Doctor consisted of extensive underground workings, beginning in 1881. He estimated production (from records and personal communication with the owner) as 12,025,262 lb zinc from 1914 to 1920 and 1937 to 1938. Later sampling showed 0-10 oz/ton Ag, 0.5 to 6% Pb and 0 - 20% Zn. He reports that "large quantities of oxidized lead-zinc ore still exists in the district." The Doctor Mine is a well-known site for mineral collectors, particularly for smithsonite.

Eberhart (Ibid) briefly discusses Petersburg, the town that serviced the Spring Creek District. More detailed geologic information is available in a 1954 Colorado School of Mines thesis by Meissner.

Taylor Park District

The Taylor Park District lies in northeast Gunnison County, in northern Taylor Park near the Pitkin County line. According to Dunn (2003) the district includes mines on the northeast and southeast slopes of North Italian Mountain and areas west and southeast of the old town of Dorchester. Vanderwilt (1947) states that the district is "not well defined"; he includes the Forest Hill Mine, which we consider within the Forest Hill District. Henderson (1926) considered the Taylor Park district as synonymous with Taylor River District, Tincup District, and Forest Hill District.

The Taylor Park District appears within the Dorchester District on the website www.mindat.org, where it also includes the iconic mineral- collecting area of Italian Mountain. Eberhart (1969), discussing the early mining camps, considered this area a part of the Forest Hill District. All these districts are discussed in the Gunnison County section of this report, but the reader must recognize the confusion accompanying their location and nomenclature.

Vanderwilt (Ibid) notes complex geology, with veins in the valley in granite. North Italian Mountain has a core of Tertiary intrusive flanked by dolomite with lead-zinc veins and replacement deposits. Fridrich et al. (1998) describe the Italian Mountain intrusive complex as ranging from quartz diorite porphyry to porphyritic dacite intruding Paleozoic rocks as young as the Belden Formation. Cunningham et al. (1994) detail the age to 33.9 Ma, using the work of Cunningham (1976). Cunningham (Ibid) interprets that the deposits in the Italian Mountain Complex are zones, with zinc-copper richer in the center and lead-silver farther away. An additional reference is Harder (1909).

Taylor Peak District

The Taylor Peak District has not been widely recognized. It appears in Dunn (2003), locating it in the Elk Mountains on the county line between Gunnison and Pitkin Counties, (obviously) near Taylor Peak. The district appears on the website www.mindat.org where it is associated with several gold placers, a uranium occurrence and a lead-zinc mine (the Thunderbird Mine). Placers of the Upper Taylor River in Parker (1974) appear to be more closely associated geographically with what we have called the Silverside District (areas of Pieplant and Illinois Creeks).

The clearest use of the name is found in Harder (1909) in his USGS publication on iron ore deposits of Gunnison County. He locates the iron ore deposits of the district along the east margins of an intrusive body northeast, east, and southeast of Taylor Peak. These deposits occur at the contact of the diorite intrusive with sediments and are named the Cooper Creek (northernmost), Twenty Percent Creek, and Taylor River (southernmost) deposits. He describes the deposits as dark blue, glossy magnetite with calcite, quartz, pyrite, kaolin, siderite, barite and chlorite as replacement bodies in limestone.

Taylor River District

The Taylor River District lies in northeastern Gunnison and is described by Dunn (2003) as including or overlapping several other districts. Henderson (1926) listed the Taylor River District in his comprehensive compilation of Colorado Districts, but named it as synonymous with the Tincup, Taylor Park and Forest Hill Districts. Vanderwilt (1947) listed the Taylor River District as equivalent to the Dorchester District. Harder (1909) discussed iron ore deposits in the Taylor Peak District, which appears to cover the same territory as the Taylor River District. The website www.mindat.org lists the Taylor River District as containing the Forest Hill Vein, and includes the Taylor River Placers with the Taylor Peak District. It's obvious that much confusion exists and none of these districts are well defined.

We have shown the Taylor River District as occupying the basin of the Taylor River between the Taylor Park and Dorchester Districts, extending east to the Silverside District. Please note that this has been done without overwhelming evidence and with less confidence.

Tin Cup District (aka Pieplant District)

The Tin Cup (or Tincup) District lies at the head of Willow Creek at the far southeast end of Taylor Park, extending east to the Continental Divide. Henderson (1926) considered the Tincup synonymous with the Taylor River District (which he in turn says is synonymous with the Taylor Park and Forest Hill Districts.) Hill (1912) also used the alternative name Pieplant District, but also included in the district mines around Taylor Park and Italian Mountain, which is inconsistent with other writers (and this compilation.) Vanderwilt (1947) used no alternative names.

Dunn (2003) points out that two spellings are used: Tin Cup and Tincup. The district adjoins the Quartz Creek District on the south with an undefined boundary. The district is on the west margin of the Mount Aetna volcanic center at the south end of the Mount Princeton batholith (Toulmin and Hammerstrom, 1990).

Numerous studies have been published on the Tin Cup District and the area directly around it. Crawford (1913) looked at the nearby Monarch and Tomichi Districts and Crawford and Worcester (1916) addressed the Gold Brick District; Goddard (1936) studied the Tin Cup District specifically. Dings and Robinson (1957) reviewed the Garfield Quadrangle, including much of the Tin Cup District. Other workers have discussed specific aspects of the area. Toulmin and Hammerstrom (1990) studied the Mount Aetna volcanic center, in which the Tin Cup lies; Belser (1956) and Sharps (1965) looked at tungsten potential and Worcester (1919) at molybdenum, all including examples in the Tin Cup District. Heyl (1964) noted examples of oxidized zinc ore in the district.

The geology is similar to other nearby districts such as Aspen and Dorchester. Proterozoic crystalline and Paleozoic sedimentary rocks are intruded by Tertiary dikes and sills. On the east side of the district is the Tincup Fault - a shallow thrust fault (Vanderwilt, 1947). Deposits of Ag-Pb-Au mantos and veins with some molybdenite and hubnerite veins characterize the district.

Economic deposits in the Tin Cup District were both bedded replacement deposits and veins (Goddard, 1936). Overall, the replacement deposits were the most important. They occurred as stratabound zones typically 8 to 10 feet thick (a few as much as 59 feet) and 30 to several hundred feet long in carbonate- rich zones at the intersection of steeply-dipping faults. They are exposed in a broad anticline trending N25W in a belt past Tincup to upper Willow Creek.

Most commonly the ore occurs in the Fremont Limestone (referred to as the Fairview Ore Horizon), but also in carbonate horizons in the Devonian Dyer Dolomite and the Mississippian Leadville Limestone. The ore contains argentiferous galena and pyrite and some sphalerite and chalcopyrite. Some "gray copper" (tetrahedrite-tennantite) is present containing silver. Silver- lead-gold veins have mineralogy similar to the replacement zones.

Total production from 1901 to 1935 was 298 oz. gold, 26,446 oz. silver, 177 lb. copper and 153,820 lb. lead (Vanderwilt, Ibid.) Heyl (Ibid) points out that while much of the ore in the district was rich in zinc, zinc was never recovered.

Tomichi District (aka Whitepine District)

The Tomichi District was first described by Hill (1909) as bounded by the divide between Tomichi and Hot Springs Creeks on the west, the divide between Tomichi and Quartz Creeks on the north and by the continental divide on the east. He notes the town of Whitepine, but does not identify a Whitepine District. Crawford presented an exhaustive, detailed description of the Tomichi District in his 1913 bulletin for the Colorado Geological Survey. He does not mention Whitepine at all.

Harder (1908), following the lead of Leith (1906) named a Whitepine District. When describing the iron deposits of Gunnison County, calls out the Whitepine District as lying on the west slope of the Sawatch Range, ten miles north of Marshall Pass.

Henderson (1926) includes the Tomichi District in his compilation, specifying the location of the district as "sections 13-16, 21-29, 32-36 of T50N, R4E and somewhat southward into T49N, R4 and 5 E."

Vanderwilt (1947) places the Tomichi District ten miles north of Sargents around the old mining camp of Tomichi, "on the east slope of Tomichi Creek." He lists the Whitepine District as synonymous with the Tomichi.

Dunn (2003) states that the district overlaps or includes the Whitepine District, while Streufert (1999) follows Vanderwilt's (Ibid) lead as indicating they are the same district.

The geology and mineralization in the Tomichi District is virtually the same as in the adjoining districts of Tincup, Quartz Creek and Monarch (in Chaffee County). Lower Paleozoic sedimentary rocks overlie and are faulted against Precambrian granitic rocks. These are all affected by the Tertiary-age intrusion of the Mount Princeton Batholith and associated smaller dikes and sills.

Streufert (Ibid) presents excellent summaries of the mineralization drawn from the earlier works. Replacement deposits occur in carbonates with (mainly) lead-silver with minor gold, copper and zinc. They range from massive sulfide to sulfide-dominated mantos 30 to 40 feet thick and up to 200 feet long (Crawford, 1913; Streufert, 1999). Ores of chalcopyrite, galena, tennantite-tetrahedrite, sphalerite with minor gold occur in a gangue of limestone, dolomite, quartz, calcite, and barite. The Morning Star Mine is an example of that type of mineralization and is described in several of the references (Hill, 1908; Crawford, 1913; Dings and Robinson, 1967; Streufert, 1999).

A second type of mineralization are fissure veins. These occur mostly west of Tomichi Creek in quartz monzonite of the Mount Princeton intrusion. Some are found in Precambrian rocks but always near the Tertiary quartz monzonite bodies (Streufert, 1999). Veins range from several inches to five feet in width, and contain native gold and silver, tetrahedrite, chalcopyrite, galena and sphalerite in a pyritic quartz gangue (Crawford, 1913).

Iron ore occurs in the district both as contact metamorphic and as bog iron replacing organics. Crawford (Ibid) describes magnetite associated with serpentine and tremolite in the contact metamorphic deposits.

Heyl (1964) notes oxidized zinc ores at the Morning Star and Victor mines and a few other mines in the district. Vanderwilt (Ibid) lists total production as 75,700 oz silver; 180 oz gold; 2,480,000 lb lead; 2,640,000 lb copper.

Vulcan District (aka White Earth District)

The Vulcan District has been described as synonymous with the Cebolla District (Henderson, 1926; Dunn, 2003; Vanderwilt, 1947; Streufert, 1999; mindat.org, 2015). Other names associated with the Vulcan in the literature have been the White Earth, the Domingo and the Powderhorn (Vanderwilt, Ibid; mindat.org).

In the series of papers in 1981 from the New Mexico Geological Society, Drobeck, Sheridan et al., and Hedlund and Olson discussed the Vulcan Mine (the defining property of the district) simply as lying within the Gunnison Gold Belt (Dubois Greenstone Belt.)

In Drobeck (Ibid) describes the Vulcan Mine (and adjacent Good Hope Mine) as the largest producer of gold in the entire Gunnison Gold Belt, with more than 25,000 ounces gold equivalent from 1898 to 1902, with more in 1919 and some production continuing into the 1930s. He describes the deposit as a lens of massive sulfide within bleached sericite schists. It is generally acknowledged to represent volcanagenic (specifically fumarolic) activity on the seabed during Precambrian times.

The Vulcan Mine is known for its suite of rare minerals, particularly tellurium and selenium-bearing minerals. The sulfur layer in the mine was enriched with selenium.

Washington Gulch Placers

The Washington Gulch Placers are mentioned specifically by Dunn (2003). The area is small, stretching about 1.5 miles from below the old town of Elkton downstream on this tributary gulch of the Slate River. The area is a sub-area of the Elk Mountain District.

The gold placers were first mentioned by Emmons (1894) who noted their productivity. Parker (1974) describes the area in detail, and notes the historic presence of coarse gold and significant yields. Parker (Ibid) noted signs of placer activity into the 1950s.

White Earth District (aka Vulcan District)

Dunn (2003) describes the White Earth District as being "broadly defined" to include many of the districts near the Gunnison - Saguache County border. Henderson (1926) says it includes the Cebolla, Hotchkiss, McDonough, and Goose Creek Districts. In mindat.org (2015), the White Earth is presented as synonymous with the Powderhorn District, while Vanderwilt (1947) lumps it with the Cebolla, Powderhorn, Vulcan and Domingo Districts. Streufert (1999) shows the White Earth as lying north of the Powderhorn District ("between Wildcat Gulch and Wolf Creek") and calls it the White Earth Tungsten Area. This appears to be equivalent (or nearly equivalent) to the Kezar Basin District of Henderson and Dunn.

It's apparent that the district is not well-defined. Here we will consider the White Earth to be the same as the Vulcan District, but no defining characteristics are presented that make the district unique.

White Pine (or Whitepine) District

Refer to the Tomichi District in Gunnison County.

Willow Creek District

The Willow Creek District was recognized by Henderson (1926) and Dunn (2003), who described it as comprising sections 11, 12, 13 and 14 of T47N, R2W. This is a small area just west of Vulcan, which includes the Midway Mine. It lies within the larger Gunnison District.

The geology of the area is described by Hedlund and Olson (1975). Ore included gold, lead, and silver.