By John H. McIntosh and Berton Braley

Technical World - December, 1909

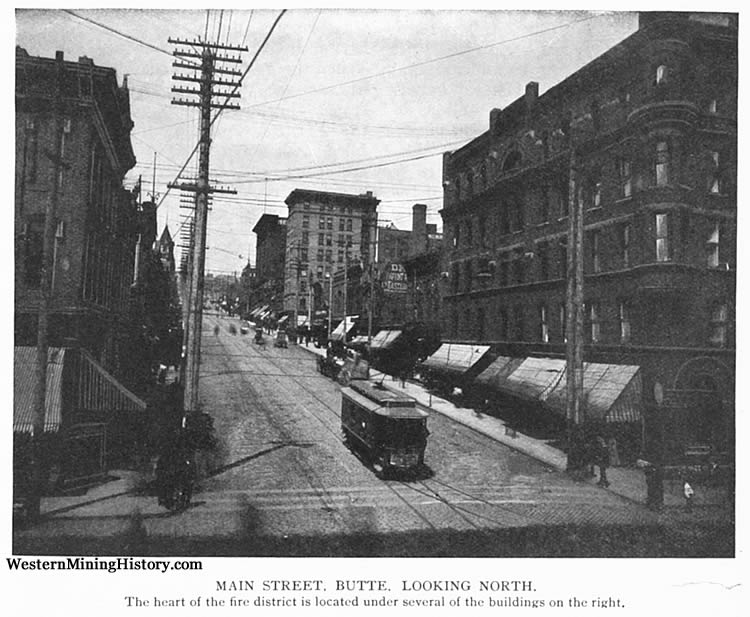

When the Berkley mine broke out afire the other day in Butte, Montana, sending five hundred men to the surface and suspending operations for a month in one of the biggest producers of the greatest mining camp on earth -- the camp that gives to the world's market one-fourth of its copper production -- the sight of the flames and smoke didn't cause as much as a ripple of excitement on the surface of the busy population at the foot of the hill, for Butte is accustomed to a mine fire that is perpetual and which burns with intense heat in the ground under her very business district.

It is a startling fact but none the less true that in the seventeen years past, thousands of men have been engaged in keeping in check the deadly fire in the Butte hill. It is a fight against a hidden foe. Except for brief intervals when the hot flames find an outlet, the fire is kept subdued by the smothering method, the theory being that it cannot spread without air on which to feed.

How it started and what keeps it alive is known to the copper miners of the northern Rockies, but the outside world has never been told, for the big companies controlling the mines have kept the talk of the wonderful fire fight down to a whisper.

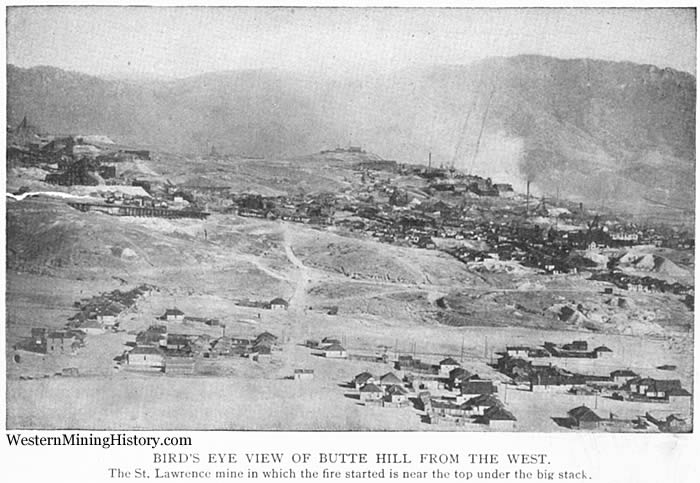

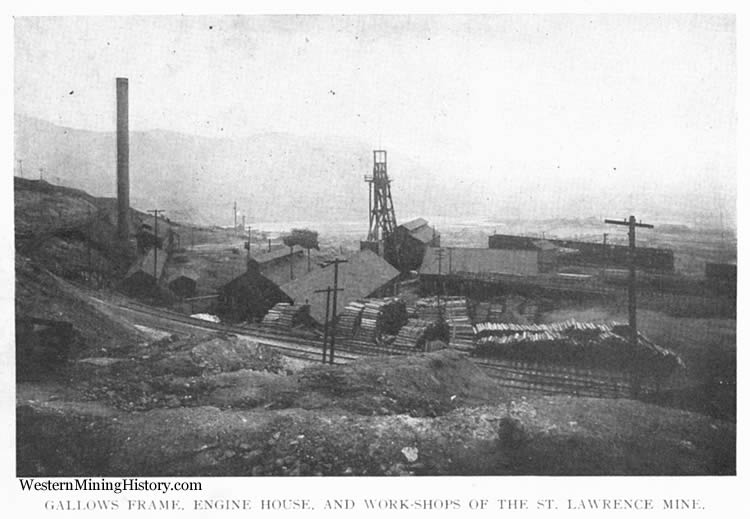

When "Big Bill" Henshaw left his candle burning on a pine stull in a stope of the 1,800 level of the St. Lawrence mine seventeen years ago he little dreamed he was starting an underground conflagration that would last for generations and which would cost millions of dollars and thousands of lives to check.

Henshaw was coming off night shift in the early morning of September 6, 1892. The burly miner had reached the mouth of the man-way at the end of the stope when his attention was called to the dim light of the candle across the black hole in the ground.

"Goin' to leave the glim there, Bill?" his partner queried.

"Sure: what's the difference?"

"Oh, nothin', only today's Labor day and the next shift don't come on 'till tomorrow. I was just thinkin' if a fire started it might spread, bein' there's nobody around."

"To Hell with it; let's go!" was the short response.

They went out, but the fire didn't.

The end of the stull touched an upright post which was part of a set of timbers and which, in turn, was part of a system of timbers as great as the mine itself.

A copper mine is timbered from the bottom up, or rather from the top down. When the first level is cut and the blocks of ore are taken out, leaving holes -- stopes -- in the ground big enough to hold the Flatiron building, these holes are filled with square sets of heavy timber and each set is filled, jam up, with worthless rock known as waste or muck. The timbering supports the weight of the ground roof above. Thus ingenious man attempts, as nearly as possible, to leave the bowels of the earth as solid as when he first sent his drill against the walls of granite to extract therefrom the precious red metal.

Then the work goes on-down, down, deeper into the earth's interior. Another level is cut, a drift for the transportation of ore and the passage of the miners is run, other stopes are worked out and in turn timbered and filled in.

The levels are one hundred feet apart. A well timbered mine seldom caves, but the man who goes below the collar of the shaft of a loosely timbered mine takes his life in his hand.

Marcus Daly owned the group of mines to which the St. Lawrence belonged at the time the fire started and the once "Copper King" timbered his mines well. And so the St. Lawrence mine, with its close timber work through its eighteen levels, at that time represented an outlay of millions of feet of seasoned timber taken from the heart of the forests all the slopes of the Rockies. This network of stulls, girths, posts and caps, intertwined amid the rock waste, extended from the bottom of the mine to the surface and covered an area of ground that, were it hollowed out, would hold all the buildings of a city of 25,000 inhabitants.

The celebration of that Labor day was rudely interrupted a few hours after the night shift had turned in. Smoke was seen issuing, not only frolll the shaft of the "Saint," as the St. Lawrence is called in the copper country of the Northwest, but also from adjacent mines whose underground workings connected with it.

And then started the fight with the flames which has lasted all these years and which will last as long as the Butte mines are worth working.

Are they worth it? Consider that one thousand millions of dollars in copper have been taken from the mines under the streets of Butte and that three thousand millions are still stored there and judge for yourself if this marvelously rich hill of red metal is not worth saving from the rapacity of the flames.

"Big Bill" Henshaw gave his life for his careless act. The miner had left his candle burning on a pine stull and his partner's fears had been realized. Henshaw waked at midnight, heard the noise and saw the smoke. Rushing up the Anaconda hill he volunteered to be the first man to go down the shaft. He was entrusted with a giant rubber hose which was to pump air into the mine in stlch volume that the smoke would be driven into other channels, thus allowing an army of miners to get down and fight the fire.

The big fellow went down the shaft but never came back alive. The incinerated remains of his massive body were afterwards found at the station of the 1,800 foot level.

Others took up the fight, however, and two days after the fire started the smoke had been pushed into connecting drifts sufficiently to allow of fire fighting below.

At first the heat and gas were terrific. Cages full of fresh men with cold, wet sheets wrapped about their stripped bodies were scnt down with rapid precision while returning cages brought up the jaded fellows who had fought as long as they could to finally wither uncler the heat.

It was found impossible to fight the fire in the rocks with water, the natural enemy of fire. The action of the water on the red hot granite is to cause steam, gas, and when applied suddenly, explosions.

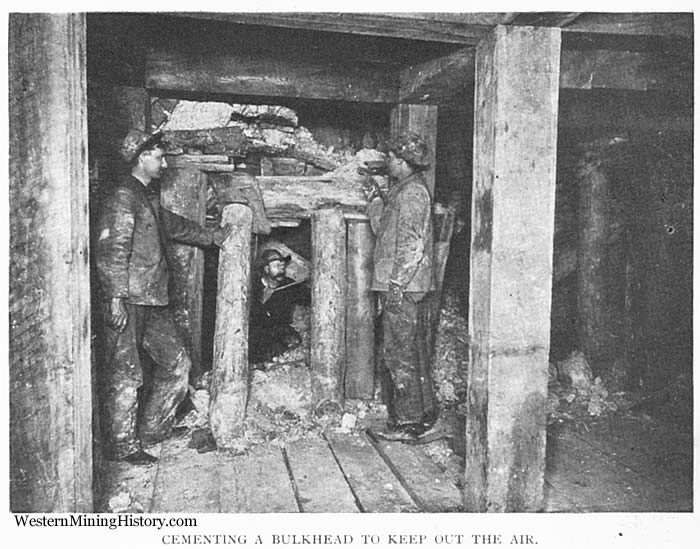

And so the object at first was to drive the flames into the deep workings of the mine and to close all avenues of air with great bulkheads of cement, limiting the territory of the flames and closing, little by little, the passages leading to the fire, thus making them air tight and smothering gradually the body of the heat center.

The underground fire affected directly the St. Lawrence, the Anaconda and the Neversweat mines, called the "Hill group." For a year following the fatal act of carelessness of "Big Bill" Henshaw, mining in these properties was practically suspended during which time the management was engaged in checking the spread of the fire. Many deaths resulted from the bitter fight with heat and flames, but in 1894 man's efforts had conquered the underground elements and the bulk of work was directed in taking out ore while a picked force of men was kept for no other purpose than to watch and keep down the fire.

Jack O'Neil is superintendent of the "Hill group" today and has been from the time in 1894 when Marcus Daly became convinced that the young Irishman was the best fire fighter out of all Butte's 10,000 miners. The Amalgamated Copper Company, which bought over the Daly interests when that great financier and "Copper King" died, will keep O'Neil as long as he lives, if for no other reason than that he knows the fire situation and can be trusted to watch the safety valves of the deep mines with eagle eyes.

Once in a long while the fire gets the upper hand of O'Neil and his force of fire fighters, as recently when flames seized the Berkley mine, but not often. O'Neil wins. He isn't the kind to lose.

Nine years ago, or during April, 1900, to be exact. Jack O'Neil conceived the idea of flooding the mines afflicted with the smouldering fire. The miners and mules were drawn to the surface, and the pumps, which had kept the water in the shaft from rising, were stopped. The water rose rapidly and in a few days had filled all the lower workings of the mines. It finally rose to the 500 foot levels. During the time the water was filling the mines steam and gas came up in great volumes to finally subside.

Then the pumps were put to work again and the water taken out. To the dismay of all interested it was found that while the flooding had cooled many places that were hot before the experiment was tried, it had actually driven the fire deeper into the rock and ore, it had failed to quench the flames. And so the old smothering method has been in vogue since.

Only occasionally in recent years has any of the fire been seen. It is deep within the earth's bowels which makes it all the harder to fight. In the vicinity of the fire the rock walls are hot as stove lids and still nearer in the rock is at white heat.

The progress of the flames must have been rapid and sure after Henshaw's candle had burned down to the piece of wood to which it had been stuck with a molten drop of wax. Once on fire the pine stull was quick to communicate its condition to the nearby set of timbers and after that the flames crept up floor after floor. The fact that each piece of timber burned was tightly wedged in between tons of rock seemed to encourage the progress of the fire rather than to discourage it.

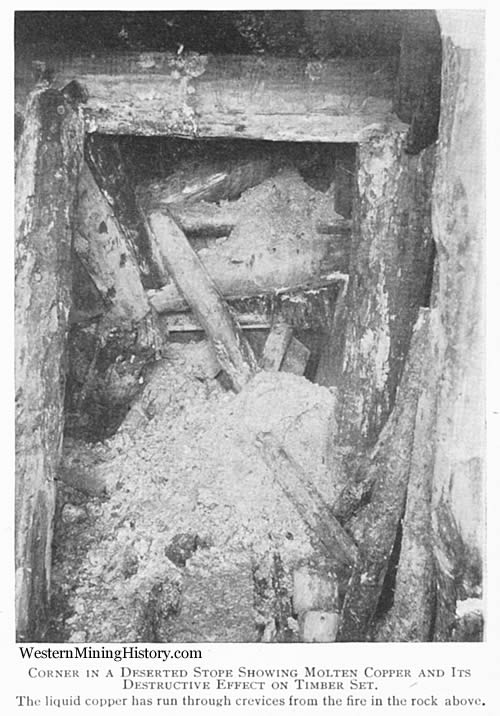

But if the fire had ceased with the burning of the timbers all would have been well. The heat became so intense that it melted the rock and copper are and all within touch became a liquid mass of white lava. It is this burning rock and copper and the gases formed by the action of the heat, which defies the efforts of man to extinguish it.

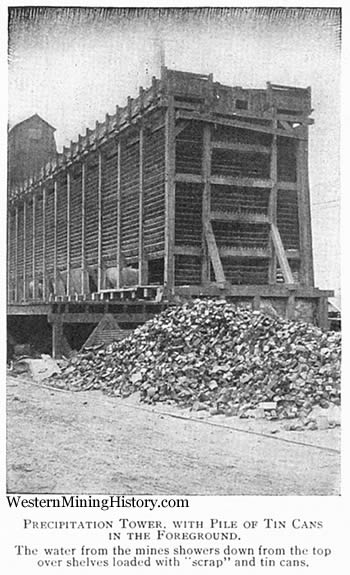

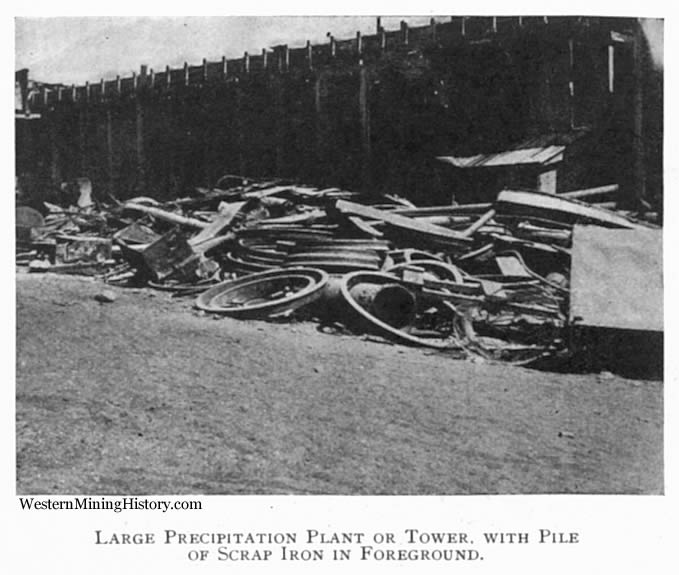

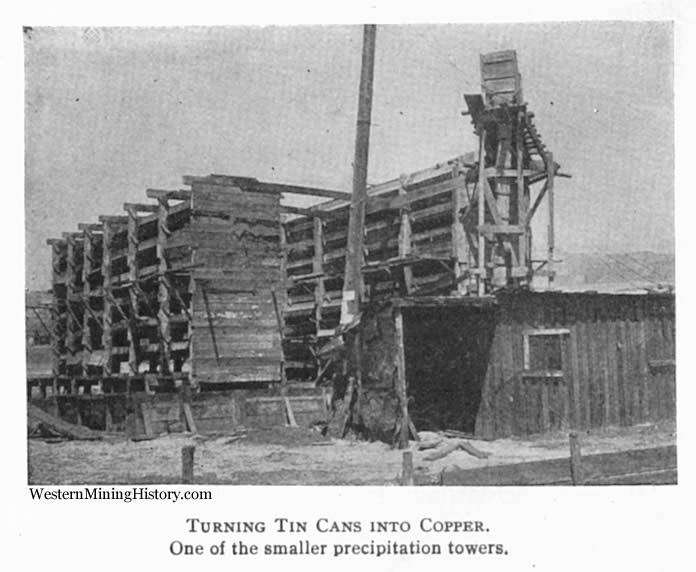

Not all the copper in the region of the fire is lost to the commercial world, however. Experiments were tried. Water was allowed to trickle through this region, the water coming out at a point near the foot of the great Butte hill a mile to the south and far below the level of the fire. Here tin cans, pieces of iron and metal scraps are gathered in great heaps and on this mass of metal the water precipitates the copper it takes up in the burning district of the mine. This saves the company no less than a million dollars a year.

Tin cans are not really tin. They are steel, covered with the thinnest possible coating of tin. And that fact explains why tin cans never accumulate in alleys and yards in Butte, just as the "affinity" of iron for sulphur, explains Butte's ever ready market for scrap iron.

For Butte turns all its tin cans, and most of its scrap iron, into copper, and does it simply by pouring the water upon them. It's water that carries from two to five per cent copper, and that process saves to Butte every month more than 800,000 pounds of valuable copper which used to run to waste down Silver Bow Creek.

"Old timers" in Butte dispute about who first discovered this process. Some attribute it to a man named Miller, who never developed much out of it, while others give the honor to W.L. Ledford, who, in 1894 certainly made the first practical application of the principles on which the business of "precipitating copper" is conducted today.

Ledford secured from Marcus Daly a lease on the waters pumped from the Butte mines under his management. That lease created a tremendous demand for tin cans and scrap iron in Butte, a demand which now gives employment to many men steadily and to many small boys occasionally, and more than that, the lease made half a million dollars for Ledford, until Daly became aware of the profits he had practically given away. Then Daly, Ledford claimed, began to precipitate copper underground, secretly, pouring out to Ledford waters almost barren of copper. Litigation followed, but Daly won out, and Ledford quit, with much of his fortune gone. but in no immediate danger of starvation.

Today, the water which gushes forth from the Butte mines at the rate of 4,000 gallons a minute, is robbed of its three per cent of copper by the iron and tin cans over which it flows, then it is sluiced upon the old mine dumps, the slag dumps from the now extinct smelters, and the miles of tailings stretching about the city. From this copper-saturated earth it sucks new supplies of the red metal, which are again taken from it by the seductive iron.

The chemistry of the process is simple. Butte's ores are sulphide ores, and the water from the mines, by seeping through miles of drifts and stapes, where the are has oxidized or where the great underground fire is raging, becomes impregnated with copper in the form of copper sulphate.

Now iron has a greater "affinity" for sulphur than has copper. That means that the chemical attraction of sulphur and iron is greater than the chemical attraction of sulphur and copper. Naturally, then, when the copper sulphate pours over the iron, the iron takes the place of the copper, and forms ferro sulphate, which is carried away by the water. Thus constantly the copper coats the iron scrap and the tin cans over which the "copper water" pours, and gradually the iron is wasted away until there remains nothing but copper, save for such impurities as mix in the product. This copper forms the "precipitates," which run from sixty to eighty per cent pure copper.

The water from which this rich treasure is lured comes mostly from the mines, It is pumped-by phosphor-bronze pumps, through wooden-lined or leaden-lined pipes, for it would destroy iron or steel in a few days-to precipitation plants at the Leonard and High Ore mines.

The High Ore is the deepest mine in Butte and to it runs, by gravity, all the water from all the Anaconda Company's mines. From the High Ore sump it is Iifted to the surface by enormous force pumps at the rate of 1,200 gallons a minute.

Into the Leonard sump drains the water from the Boston and Molltana mines, further down on the "copper hill" where Butte's ore bodies lie, Here anolher mighty pump thrusts the water to the surface at 1,100 gallons a minute.

At the Hgh Ore and the Leonard are great precipitation plants, where the water is showered down through a series of shelves filled with old scrap iron and tin plate. The copper in solution, as explained above, encrusts itself upon the iron, to wait until the iron is entirely supplanted by copper is much too slow, and every few clays the men who run the plant "clean up," by diverting- the water from a particular part of the "tower"-as they call the arrangement of shelves-scraping or knocking loose the copper from the iron, shoveling it into sacks or barrels, and taking it to the dryer. From the dryer the precipitates are sent to the smelters, where they are cast into ninety-nine per cent copper ingots.

But that is not all the history of the mine waters, for they are seized upon anew, when they have traversed the mine precipitation plants, pumped to the top of some old mine dump or slag dump, where great pools are formed, and left to seep through the sands or the slag into tunnels bored beneath. From these tunnels the "enriched" water is again lifted to precipitation "towers" where the iron once more begins its work, and the copper is again lured from the waters. It takes about a pound and a half of iron to precipitate a pound of copper. Scrap iron sells for one-fourth cent a pound, copper for thirteen cents-just now.

There is no limit to the number of times the precipitation process can be repeated, so long as there are dumps or tailings upon which the water can be directed. Nor need it be mine water, for all along Silver Bow creek the pumps are chugging industriously as they lift the water to the dumps and relift it to the top of the precipitation towers. There are hundreds of these, and there are miles of trestle to carry the waters out upon the dumps and the tailing piles.

It pays. The mines must be kept dry and pumping would therefore be a necessary expense under all circumstances, yet the Easton and Montana and the Anaconda companies after paying for the drainage of all their mines, realize a profit of about six cents upon every pound of copper that is recovered in this way.

The leaders who "leach" the dumps, must expend about six cents for every pound of copper obtained, but that copper brings them thirteen cents at the present market. Were it not that the big companies demand twenty-five and thirty-five per cent royalty on the net proceeds, the profits would be much higher.

Thus Butte converts what once was pure waste into an annual saving of nine million pounds of copper, worth about a million and a quarter dollars, one-half of which is clear profit.

So, as stated at the outset of this article, the people of Butte are not excited or worried over the fire which is directly under the business district of the busy camp of 70,000 people. Alarmists have declared that some day the effect of the fire will be to cause a great void under Butte and that the camp will be swallowed suddenly into this deep, hot hole in the ground. but the population is too busy to attend to such prophesies, and they seem willing to take the chance.

And the underground fire goes burning on.