The Plumas-Eureka Mine is a gold mine located in Plumas county, California at an elevation of 5,495 feet.

About the MRDS Data:

All mine locations were obtained from the USGS Mineral Resources Data System. The locations and other information in this database have not been verified for accuracy. It should be assumed that all mines are on private property.

Mine Info

Elevation: 5,495 Feet (1,675 Meters)

Commodity: Gold

Lat, Long: 39.7566, -120.70080

Map: View on Google Maps

Plumas-Eureka Mine MRDS details

Site Name

Primary: Plumas-Eureka Mine

Secondary: Mammoth Mine

Secondary: Eureka Peak Mine

Secondary: Rough and Ready Mine

Secondary: Washington Mine

Secondary: Seventy-Six Mine

Secondary: Lawton Vein

Secondary: North Vein

Secondary: Eureka Vein

Secondary: Eureka Claim

Secondary: Director Claim

Secondary: Director 1 Claim

Secondary: Director 2 Claim

Secondary: Oceola Claim

Secondary: Oliver Claim

Secondary: Johns Extension Quartz Claim

Secondary: Eureka Peak Quartz Claim

Secondary: Mammoth Claim

Commodity

Primary: Gold

Secondary: Lead

Secondary: Silver

Tertiary: Iron

Tertiary: Zinc

Tertiary: Copper

Tertiary: Arsenic

Location

State: California

County: Plumas

District: Johnsville District

Land Status

Land ownership: State Park

Note: the land ownership field only identifies whether the area the mine is in is generally on public lands like Forest Service or BLM land, or if it is in an area that is generally private property. It does not definitively identify property status, nor does it indicate claim status or whether an area is open to prospecting. Always respect private property.

Administrative Organization: California Dept. of Parks and Recreation

Holdings

Not available

Workings

Not available

Ownership

Owner Name: California Department of Parks and Recreation

Production

Not available

Deposit

Record Type: Site

Operation Category: Past Producer

Deposit Type: Hydrothermal vein

Operation Type: Surface-Underground

Discovery Year: 1851

Years of Production:

Organization:

Significant: Y

Deposit Size: M

Physiography

Not available

Mineral Deposit Model

Model Name: Low-sulfide Au-quartz vein

Orebody

Form: Tabular, lens

Structure

Type: L

Description: No significant local structures

Type: R

Description: Melones Fault Zone, Mohawk Valley Fault Zone

Alterations

Alteration Type: L

Alteration Text: Negligible - None described

Rocks

Name: Rhyolite

Role: Host

Description: tuff

Age Type: Host Rock

Age Young: Late Devonian

Name: Tuff

Role: Host

Description: Rhyolite

Age Type: Host Rock

Age Young: Late Devonian

Name: Porphyry

Role: Host

Description: Porphyritic igneous rocks

Age Type: Host Rock

Age Young: Late Devonian

Name: Gabbro

Role: Host

Age Type: Host Rock

Age Young: Late Devonian

Analytical Data

Not available

Materials

Ore: Gold

Ore: Chalcopyrite

Ore: Galena

Ore: Sphalerite

Ore: Arsenopyrite

Gangue: Quartz

Comments

Comment (Development): Shortly after their purchase in 1872, the Eureka Mill collapsed. This lead to the construction of the huge new Mammoth Mill with 40 stamps (later enlarged to 48), near the mouth of the upper Mammoth Tunnel. The Mammoth Mill relied on water power from Eureka Lake, but had auxiliary steam power. The company stockpiled 3,000 cords of wood, enough to run the works for a year if water became scarce. They also enlarged and retimbered the Mammoth Tunnel and prepared to drive a Lower Mammoth Tunnel, which would also provide ore handy to the mill. A flume to bring Eureka Lake water power to the mill was also installed. The new mill began crushing ore in 1873. Even the Rough and Ready came through when exploration of an old tunnel opened a new ore vein. Good leads were also developed in tunnels of the old Seventy-Six near the top of the peak. The discovery of new orebodies in the old tunnels was largely responsible for construction of the new Mohawk Mill and the erection of a high-line gravity cable tramway to bring the ore down. After the new Mammoth mill went on line in 1873, plans were made for a second huge 40-stamp mill. It began crushing ore with 20 stamps in December, 1878. The second 20 stamps went online in January 1879. The Mohawk mill operated in conjunction with the Mammoth mill. The Mohawk mill wheel was driven by water from a miners ditch, which tapped Jamison Creek two miles up the canyon. During 1876, William Johns (the mine manager) laid out a townsite along Jamison Creek to support the new mill operation at the base of the mountain. The town came to be known as Johnsville, which still survives to this day. Throughout the 1880s, ore values began to steadily decline. Through the last good year, the company cleared $7/ton on ore assaying $12/ton. But as the ore values dropped to $10, $8, to $6, work stopped at the Seventy-Six and the Rough and Ready; 20 of the Mammoth's stamps were moved to the Mohawk mill. Dividends, for long 15% a year, dropped to 10% in 1884, then 5%, and finally 2.5% in 1886. In 1888 average yield of ore was $7.92/ton with mill tailings assaying $2/ton. Employment had dropped to 200 men in 1888. By 1888, the main tunnel was 6,000 feet long and the vertical depth reached in the mine was 1,500 feet. Three gravity tramways (500 feet, 1,500 feet, and 1,700 feet long) were in operation to transport ore from the mines to the mills. Ore cars were brought out by horses and conveyed to the mill by the tramways. By 1890, the Plumas-Eureka Mine was in decline and employed 229 men. Through the years, the mine had been opened by five tunnels to tap the Plumas-Eureka vein to a vertical depth of 1,500 feet. Three of these had been worked out, and the remaining two were idle. Small quantities of ore were still being taken from the Seventy-Six vein, but the ore quality was poor. It averaged less than $5/ton, which scarcely paid for its extraction and processing, but was enough to keep the Mohawk mill operating. Recovery in the batteries averaged 60%, the remainder being found on the plates. The amalgam yielded 20% of its weight in gold when retorted. The pulp, after passing over the amalgamating plates and concentrators, was passed down the creek to be worked by almost 30 arrastras situated one below the other down the canyon. In March of 1892, the town of Johnsville was largely destroyed by fire. Due to the declining fortunes of the Plumas-Eureka, it was never completely rebuilt.

Comment (Location): The location point selected for latitude and longitude is the main Eureka Tunnel adit symbol on the USGS Johnsville 7.5-minute quadrangle. The mine is located within the Plumas-Eureka State Park, which is owned and operated by the California Department of Parks and Recreation. Access is via County Highway A14 (Graeagle-Johnsville Road) approximately four miles southwest of Mohawk, California, to the Plumas-Eureka State Park Headquarters and Museum. The Mohawk Mill and Eureka Tunnel are located about 500 feet west of the headquarters.

Comment (Workings): The workings of the Plumas-Eureka Mine are confined to the east side of Eureka Peak from near its summit to its base on the banks of Jamison Creek. The complexity of the many veins, offshoots, and flat veins make a description of the mine workings impossible without the aid of maps. Further, many of the details of early and later workings conflict, or are absent. Generally, however, five main tunnels were opened up over the years on the main Eureka vein, these being the Eureka, Mammoth, Mohawk, Railroad, and Cropping Hills tunnels. They vary in length from 7,300 to 450 feet in length, the respective lengths of the Eureka (lowermost) and Cropping Hill tunnels (uppermost). The upper tunnels are the Cropping Hill and Railroad Tunnels located between 1,200 and 1,500 feet above Jamison Creek in the valley below. Almost 900 and 600 feet above the valley floor are the Mammoth and Mohawk tunnels, respectively. The main Eureka Tunnel is at the base of the mountain near the Mohawk Mill. Including these tunnels, some 62 miles of underground workings are said to have been driven by the time the Sierra Buttes Mining Company ceased operations in 1902. Unlike conventional mining methods, the ore bodies of the Plumas-Eureka were exploited from the top down. This is largely in part due to the early 1851 discovery of the Eureka vein outcrop by the Eureka Company and the competing operations of the Rough and Ready, Mammoth, and Seventy-Six mines located adjacent to the original Eureka claims. These mines operated independently for over 20 years, each exploiting its own claims, until they were consolidated and operated as the Plumas-Eureka Mine by the Sierra Buttes Mining Company in 1873. While the Sierra Buttes Mining Company did open the Eureka Tunnel at the base of the mountain, they never made a concerted effort to connect all the overlying workings in a systematic manner and block out all the ore. SBMC did, however, sink two winzes 200 feet deep below the Eureka tunnel and drive a drift on the vein blocking out 115,000 tons of ore that was never removed. As late as 1910, it was recognized that considerable ore remained in the Eureka vein below the lowest working levels in the Eureka Tunnel. On more than one occasion, the Johnson Graham Mining Company and Plumas-Eureka Mines Inc. planned to open a new and deeper tunnel to access and stope the overlying ore, but the work was never completed. At present on Eureka Peak, physical access to all known workings that daylight is restricted by cyclone fencing, which was completed last year.

Comment (Geology): Other important veins include the Seventy-Six vein, which can be traced for 2400 feet towards the south and dips from 10 to 25 ? to the east, southeast and south; the Rough and Ready vein, which strikes a few degrees west of north and dips 71 degrees east; and the Jamison vein, which averages six feet thick, trends north 20? west, and dips 35-40? west. The Jamison vein also appears as a primary ore body in the neighboring Jamison Mine. All the veins vary in thickness throughout their lengths, from a few inches to more than 20 feet. Commonly from 2 - 6 feet of ore is found between the walls. One of the noteworthy characteristics of many veins is their sharp definition, with unbroken walls being traceable from one end of the vein to the other. In these cases, there is little waste found in the ore due to the regular and clean nature of the walls. An unusual phenomenon exhibited by some of the veins is their tendency to roll over, flatten, and reverse their dip taking on an anticlinal configuration. While this is more common in the neighboring Jamison Mine, this dip reversal also occurs in the Plumas-Eureka Mine within the Eureka Flat vein, Mohawk Flat Floor vein, and the Seventy-Six Flat vein, and Jamison vein. Higher gold values typically accompany this flattening. Ore is free-milling quartz vein material being about 0.814 fine (ore values consist mainly of gold with little silver). The gold is finely divided. A number of high-grade pockets were taken from the surface in the early days. The main sections of veins are commonly low-value, milky bull quartz. Gold values are generally lean in this material and increase along the vein walls. Occasionally, rich ore shoots are found within the veins. Gouge material sometimes occurs on the foot and hanging walls and also carries values. Sulfide content is variable, commonly consisting of abundant pyrite and varying amounts of galena, chalcopyrite, sphalerite, and arsenopyrite. Generally, sulfide content ranges from a trace to 1.5%, but where veins pinch, sulfides can run as high as 30%. Based on available information, sulfide mineralization was confined to the quartz veins and thin bordering gouge zones. No reference to or indication of sulfide mineralization or alteration of the wall rock is available. Sulfides were treated with chlorination until the early 1900s, after which they were treated by cyanidization.

Comment (Deposit): The Plumas-Eureka Mine was the most productive gold mine in Plumas County. During its operations, which spanned some 91 years (1851-1942), it consisted of 2500 acres consolidated from several previously independent claims, and controlled both the timber and water rights (vital to early mining) to most of the neighboring area. The Plumas-Eureka gold deposits occur in fissure-filling hydrothermal quartz veins within lower Devonian metavolcanic island-arc rocks of the Sierra Buttes Formation. The veins cut several lithologies including gabbro, pyroxenite, quartz porphyry, diorite, and rhyolitic tuff. During the upper Jurassic Nevadan Orogeny, much of the Sierra Nevada was metamorphosed and folded into a complex series of parallel northwest trending folds and reverse fault complexes, arguably the most famous of which is the Melones Fault Zone. The Melones Fault Zone forms the western boundary of the Northern Sierra Terrane, one of four major lithotectonic blocks in the northern Sierra Nevada, and within which the Plumas-Eureka Mine is located. During and shortly after this upheaval, low-sulfide, native gold-bearing hydrothermal veins were emplaced throughout much of the western Sierra Nevada. At least five significant gold bearing veins including the Eureka, Mammoth, and Seventy Six veins and numerous smaller offshoots were exploited. Gold is finely divided and the ore free milling. Fineness is approximately 0.815. The quartz veins are roughly parallel and generally trend northeast-southwest, but some are reported to diverge to as far as a few degrees west of north. Dips are variable, with the Eureka vein being the most consistent and dipping 75? northwest, whereas the Seventy-Six vein dips from 10-25? east, southeast and south. In some cases vein dips flatten and roll over into an anticlinal form yielding areas of almost horizontal veining. The Eureka vein ranges from a few inches to 40 feet wide but averages 6 feet. The quartz is typically milky white bull quartz. Gold values are low in this material and generally increase towards the vein walls, where veins thin, and where veins flatten. Based on the similar geologic setting, age, and mineral assemblages, the Plumas-Eureka veins are thought to be mesothermal deposits contemporaneous with other veins in the Sierra Nevada that have been documented as mesothermal. Fluid inclusion and paragenetic mineral assemblage studies in the Alleghany District of the northern Sierra Nevada (Coveney, 1981) are consistent in placing mineralization temperatures of quartz veins there at between 200?- 325?C and pressures up to 2.5 kilobars. Unlike many important mines in the Sierra Nevada, records and descriptions of the Plumas-Eureka Mine suggest little alteration of the wall rock with the exception of relatively thin gouge zones bordering the veins.

Comment (Commodity): Commodity Info: Free-milling gold-bearing quartz veins with auriferous sulfides. Gold averaged 0.814 fine with secondary silver. Ore averaged 0.5 to 1.45 ounces/ton, with richer pockets near the surface. Sulfides included abundant pyrite and varying amounts of galena, chalcopyrite, sphalerite, and arsenopyrite. Sulfide content ranged from a trace to 1.5%, but reached as much 30% where veins pinched.

Comment (Commodity): Ore Materials: Native gold, chalcopyrite, galena, sphalerite, arsenopyrite

Comment (Commodity): Gangue Materials: Quartz

Comment (Identification): The Plumas-Eureka Mine consists of a consolidation of several early mines discovered in 1851 on the east flank of Eureka Peak (formerly Gold Peak) and operated independently until 1871 when the claims were purchased by the Sierra Buttes Mining Company, Ltd. (SBMC) of London, England. Previously known as the Eureka, Rough and Ready, Seventy-Six, and Mammoth Claims, SBMC consolidated and operated them under the banner of the Plumas-Eureka Mine. At the height of its operation in the 1890s, the Plumas-Eureka Mine property comprised approximately 2,500 acres, which included 788 acres of prime timber and water rights essential to the operation of the mine. In the 1890s, gold-bearing quartz deposits of the same lode were also found on a property approximately one mile south and adjoining the property of SBMC's Plumas-Eureka Mine. These outcrops were developed independently as the Jamison Mine by the Jamison Mining Company.

Comment (Geology): Regionally, the northern Sierra basement rocks are overlain by a series of Tertiary volcanic and sedimentary rocks of mostly Miocene and Pliocene age. The oldest of the Tertiary units in the area is a basal conglomeratic unit commonly referred to as Eocene auriferous gravels. The gravels are preserved in paleochannels eroded in the basement surface. In contrast to the earlier volcanism, Tertiary volcanism was continental and deposited on top of the eroded island arc rocks and Mesozoic intrusives. As many as eight different volcanic units blanket large portions of the area ranging from the lower Lovejoy basalt to widespread andesitic flows and breccias. The youngest deposits include Quaternary sediments. Extensive beds of Quaternary alluvium and Quaternary morainal and glaciofluvial debris blanket much of the region. Structure Most upper Jurassic and earlier rocks of the northern Sierra Nevada were metamorphosed and deformed during the Jurassic-Cretaceous Nevadan Orogeny (Clark, 1960), the primary expression of the Jurassic amalgamation of oceanic terranes with the Mesozoic continental margin (Moores, 1972; Saleeby, 1981; Schweickert and Cowen, 1975). The dominant northwest trending structural grain of the Northern Sierra Terrane is a result of this period of compressive deformation, which produced east-directed thrust faults, major northwest-trending folds, and regional greenschist facies metamorphism (Harwood, 1988). This episode also resulted in many of the intrusions of granitic plutons that formed the Sierra Nevada. However, all the main lithotectonic belts of the northern Sierra Nevada also contain rocks that have undergone significant pre-Nevadan deformation and metamorphism. While the nature and extent of pre-Nevadan deformation is poorly understood, the principal expression of this earlier deformation is a cleavage or metamorphic foliation that dips steeply and strikes north-northwest (Day, 1988). Nevadan deformation structures within the northern Sierra Nevada lithotectonic blocks are steeply dipping northwesterly trending faults and folds. These faults are best developed in the Eastern, Central, and Feather River Peridotite Belts, where they have been collectively described as the "Foothills Fault System" (Clark, 1960). They deform upper Jurassic rocks and are truncated by uppermost Jurassic and Cretaceous plutons. Where the attitude can be determined, most of the bounding faults dip steeply east and display reverse displacement. Significant structural deformation in the area was absent from the end of the Cretaceous to the Pliocene or Quaternary. Two fault zones of Pliocene(?) and Quaternary age occur in the area. The Mohawk Valley Fault Zone, which lies to the east of the Plumas-Eureka Mine, trends north-northwest, is normal and down to the west, and suggests over 1,000 feet of dip-slip displacement with a minor right slip component (Jennings, 1994). The Mohawk Valley Fault Zone has been ascribed as the eastern front of the Sierra Nevada, but more likely represents a zone within the Sierra Nevada that is transitional to the Basin and Range province (Grose, 2000). The Grizzly Valley Fault Zone is northeast of the Mohawk Valley Fault Zone and strikes northwesterly. About a mile wide, the zone is composed of down to the west, left-stepping, high-angle normal faults with estimated dip- slip displacement of a few hundred feet. Metallogeny The northern Sierra Nevada harbors many individual mining districts, each known for important deposits of lode and/or placer gold. Lode gold occurs primarily as native-gold ore shoots within hydrothermal quartz veins and, to a lesser degree, in low-grade altered wall rocks.

Comment (Geology): The Eastern Belt, more commonly called the Northern Sierra Terrane, underlies the Johnsville District and is separated from the Feather River Peridotite Belt to the west by the Melones Fault Zone. To the east are the Mesozoic plutonic granitic rocks of the Sierra Nevada Batholith. The Northern Sierra Terrane is primarily composed of Devonian to Jurassic metavolcanic rocks and the earlier Shoo Fly Complex. The Shoo Fly Complex is a sequence of siliclastic metasedimentary basement rocks of continental origin. The dominant provenance of Shoo Fly sedimentation was the North American continental crust. The Shoo Fly Complex also contains shale- matrix melanges containing serpentinite, limestone, phyllite, and chert that developed in a trench setting. Unconformably overlying the Shoo Fly Complex is a series of three superimposed upper Devonian to Jurassic island- arc sequences (Brooks, 2000). The earliest volcanism is recorded in the upper Devonian - Pennsylvanian (?) Taylorsville Sequence, which includes the Grizzly, Sierra Buttes, Taylor, and Peale Formations. Later episodes of volcanism are preserved in the Permian - Triassic Arlington, Goodhue, and Reeves Formations and the Jurassic volcanic rocks of the Sailor Canyon Formation. In the area of the Plumas-Eureka Mine, only the older rocks of the Shoo Fly Complex, Sierra Buttes Formation, and Taylor Formation are exposed where not obscured by extrusive Tertiary volcanic rocks or later Quaternary alluvium. Rocks of the Peale Formation and later island-arc sequences occur farther northeast. The Taylorsville Sequence consists of submarine volcanic and volcaniclastic rocks and radiolarian chert of the Grizzly, Sierra Buttes, and the lower member of the Peale Formation. The Grizzly Formation is present only locally along the unconformity between the Shoo Fly Complex and the Sierra Buttes Formation. Near its type location, the Sierra Buttes Formation consists of four major units. The lower three units are primarily rhyolitic to dacitic in composition. The upper unit is primarily andesitic. All four units contain thick, discontinuous beds of lapilli tuff, tuff breccia, tuffaceous turbidites, and argillite with interbeds of carbonaceous and phosphatic chert, and laminated tuff (Hanson, 1983) intruded by rocks ranging from gabbro to rhyolite. Hanson interpreted these deposits to be submarine mass-flow deposits produced by eruption or slumping of near-vent accumulations within a volcanic island-arc sequence. The Sierra Buttes Formation is conformably overlain by andesitic submarine volcanic and volcaniclastic rocks of the Taylor Formation. It consists primarily of andesite breccia, massive and pillowed andesite and basaltic andesite flows, and andesitic volcaniclastic turbidites. Overlying the Taylor Formation is the Peale Formation, which consists of a lower volcanic-volcaniclastic member and an upper chert member. The lower member contains massive trachytic to quartz latite flows, tuff breccia, tuff, tuffaceous siltstone, and sandstone (Harwood, 1988) and grades upward into siltstone, sandstone, and limestone. The lower member grades abruptly into a thin bedded black, red, green, and gray radiolarian chert member that serves as a widespread marker unit in the region. The Peale Formation records the waning stages of Late Devonian and Early Mississipian submarine arc volcanism (Grose, 2000). The chert member, which includes bedded radiolarian chert and other pelagic and siliceous sediments, reflects regional subsidence of the volcanic arc to abyssal ocean depths.

Comment (Geology): INTRODUCTION The Plumas-Eureka Mine is located in the Johnsville Mining District in south central Plumas County. The district is both a lode and placer gold district at the north end of a belt of mineralization extending about 20 miles southward into Sierra County and including the Sierra Buttes Mine ($17-$20 million produced) at its south end. The district is noted for varied exposures of slate, schist, quartzite, metadacite, quartz porphyry, greenstone, and numerous mafic and felsic intrusives. Portions of the district are overlain by Tertiary andesite and/or glacial debris. The Plumas-Eureka Mine has the distinction of being one of the oldest lode gold mines in California as well as being the preeminent and most profitable gold mine in Plumas County. Operations were conducted from 1851 until the 1940s. REGIONAL SETTING The northern Sierra Nevada is home to numerous placer and lode gold deposits and includes many of the more famous gold mining districts such as Grass Valley, Nevada City, Allegheny, Downieville, Eureka, Rich Bar, La Porte, and Johnsville districts. The geological and historical diversity of most of these deposits is covered in numerous publications produced over the years by the U.S. Bureau of Mines, U. S. Geological Survey, California Division of Mines and Geology (now California Geological Survey), and others. Additional information on the geology and history of the Plumas-Eureka area is contained in publications and exhibits available at Plumas-Eureka State Park and in the archives of the Plumas County Museum. The most recent geologic mapping in the area is a 15-minute scale compilation of the Blairsden Quadrangle by Grose (2000). Stratigraphy The northern Sierra Nevada has a history of both oceanic and continental margin tectonics recorded in sequences of oceanic volcanism, near-continental volcanism, and continental volcanism that can be divided into four major lithotectonic belts. These belts are the Western Belt, Central Belt, Feather River Peridotite Belt, and Eastern Belt (Day, 1988). The Western Belt is composed of the Smartville Complex, a late Jurassic volcanic arc complex (Beard and Day, 1987). Rocks are basaltic to intermediate pillow lavas overlain by pyroclastic and volcaniclastic rock units with diabase, metagabbro, and gabbro-diorite intrusives. This belt is bounded to the north and east by the Big Bend-Wolf Creek Fault Zone. To the west, it is unconformably overlain by the Cretaceous Great Valley sequence. The Central Belt is bounded to the west by the Big Bend-Wolf Creek Fault Zone and to the east by the Rich Bar and Goodyears Creek faults. The Central Belt is structurally and stratigraphically complex and consists of metamorphosed Mississippian - Triassic chert, argillite, phyllitic argillite, ophiolite, and greenstone of marine origin. It is equivalent to the Calaveras Complex of central and southern Mother Lode of the Sierra Nevada. The Feather River Peridotite Belt is also fault bounded separating highly deformed Central Belt from the rocks of the Eastern Belt for almost 95 miles along the strike of the northern Sierra Nevada (Day, 1988). The Feather River peridotite belt consists largely of Devonian to Triassic serpentinized peridotite and dunite.

Comment (Geology): Most significant exposed deposits have probably been discovered given the intense scrutiny the area was subjected to during the latyer half of the 19th century. However, there are undoubtedly undiscovered deposits in the region. Deposits might exist where the veins do not crop out or where surface exposures do not reflect mineralized ore shoots at depth. Zones of barren quartz commonly separate known ore shoots within veins. More likely would be deposits concealed under the extensive covers of Tertiary volcanic rocks and Quaternary alluvium and glacial debris. In regards to the Plumas-Eureka Mine, additional low-grade ore and possibly high-grade shoots likely remain in the deeper reaches of the mine that were not exploited prior to the mine's closure. Since the mine and adjacent properties are now a State Park, further exploration or development is highly unlikely. GEOLOGY AT THE PLUMAS-EUREKA MINE A variety of Ordovician to Jurassic volcanic and sedimentary rocks comprising the lower sections of the Northern Sierra Terrane are exposed in the area of the Plumas-Eureka Mine. Rocks are metamorphosed and exhibit extreme schistosity and foliation. Rocks of the Shoo Fly Complex and portions of the lower Taylorsville Sequence including the Sierra Buttes Formation and Taylorsville Formation are exposed in a north-northwesterly trend. Rocks of the overlying Peale Formation are not exposed, and if present, are obscured by Quaternary glacial morainal material, alluvium, or Tertiary volcanic rocks. The west flank of Eureka Peak is composed of the Sierra City Melange Unit of the Shoo Fly Complex. This unit represents the structurally highest of four thrust blocks comprising the Shoo Fly subduction complex and is composed of blocks of serpentinite, gabbro, basalt, sandstone, limestone, mudstone, and chert within a sheared sandstone and shale matrix. Comprising Eureka Peak itself and the eastern flank of the mountain are rocks of the Sierra Buttes Formation, which consist locally of submarine rhyolitic to andesitic tuff interbedded with lenses of black phosphatic radiolarian chert and siliceous argillite. In the upper part, andesitic tuff and tuff breccia prevail. The Sierra Buttes Formation is highly disrupted by intrusions of gabbro, pyroxenite, quartz porphyry, and diorite. The principal intrusive is gabbro, which forms most of the exposed east slope of Eureka Peak and carries many of the veins. Pyroxenite forms most of the northeast slope. Elongate inclusions of quartz porphyry are often found within the gabbro and are commonly associated with the veins. East and north of Eureka Peak, are two extensive glacial moraines and related alluvium that cover the Sierra Buttes Formation to considerable depth. The Plumas-Eureka ore bodies consist of a complex system of at least five main fissure-filling hydrothermal quartz veins much like the typical gold-bearing quartz veins of the California Mother Lode of the Sierra Nevada foothills. Veins trend northeast-southwest, are roughly parallel with divergent dips, and cut the various lithologies in the Sierra Buttes Formation primarily, quartz porphyries, gabbro, and argillite. The principal Eureka Vein strikes northeast-southwest and dips 75? northwest. It varies from 2-40 feet wide, but averages six feet thick. It is more regular in its course than many of the other veins. For a good portion of its length the vein is at or near the contact between quartz porphyry and gabbro. This vein is the original outcropping vein discovered in 1851.

Comment (Development): The Plumas-Eureka lode was discovered by a party of prospectors in search of a mythical Gold Lake in the Sierra Nevada. While two members of the party were climbing to the top of Gold Mountain (later renamed Eureka Peak) to reconnoiter, they found a rich outcropping quartz vein about 1,500 feet above the valley floor on May 23, 1851. The vein was 20 feet wide, 400 feet long, and stood 4 feet above the ground. The mountainside was also covered with rich quartz float. What they found was the exposed top of the Eureka Chimney, a gold-bearing vein that wouldn't be worked out until 1865. The prospectors recruited friends to open a gold mine on the mountain. They assembled a total of 36 members. They named the vein Eureka and formed the Eureka Company, the first company incorporated for mining purposes in California and which began operations in 1851. The Eureka Company staked 30-foot square claims for each of its members, took possession of the nearby Eureka Lake water rights, and erected some arrastras. In 1855 they put up a 12-stamp mill followed in 1857 by a 16-stamp mill to which 8 more were added in 1870. Both were below Eureka Lake Dam at the head of a steep ravine to take advantage of the water drop. As word spread, another group of 76 men located another quartz outcrop on the mountain. They organized their own company and named their mine the Seventy-Six Mine. They also located a mill site on Jamison Creek. Another group of 40 men located outcrops on the southeast side of the mountain and called themselves the Rough and Ready Company and their claims the Rough and Ready Mine. Yet another group of some 80 men formed the Mammoth Mine immediately north of the Eureka Claim. They were satisfied with what could be done with arrastra until the spring of 1856 when they erected a 12-stamp mill along Jamison Creek. As more and more newcomers arrived they became a majority and to accommodate them all, claims were reduced to 20-feet square. The various mines were not immediately successful. The Seventy-Six mine lasted one year. They had invested in a 16 stamp-mill on Jamison Creek and a 1,500-foot wooden chute to bring ore from the mine to the mill. They also laid out a townsite calling it the "City of 76". When they started the mill in 1852, it yielded only $200 from 42 tons of rock. The company failed, the mill was torn down, and the City of 76 never prospered. The Rough and Ready Mine also fared poorly. After building a 12-stamp mill on Jamison Creek, they worked the mine until 1854, suspended operations until 1857, and shut down again shortly thereafter. Both the Eureka and Mammoth continued on and eventually prospered, becoming the core of the Plumas-Eureka Mine. In 1870, a San Francisco banker purchased both the Seventy-Six and Rough and Ready Mines, having previously obtained the Eureka claims and the main Eureka Mill. In 1872 he sold the properties to the Sierra Buttes Mining Co Ltd (SBMC) of London England for $1,000,000. SBMC formed the town of Eureka Mills high on the mountain near the mine and mill to support these operations and by the fall of 1872, SBMC employed 326 men. In 1873, SBMC bought the Mammoth Mine for $50,000, and paid another $50,000 for a claimed northeast extension of a Mammoth lead. Thus all existing operations were consolidated into the Plumas-Eureka Mine, which at its peak comprised a total of 2500 acres including 788 acres of water rights and timber lands.

Comment (Economic Factors): The Plumas-Eureka Mine is one of the most productive gold mines in the northern Sierra Nevada and the preeminent gold mine in Plumas County. Extravagant claims of up to $20 million have been attributed to the Plumas-Eureka during its lifetime from 1851 to 1942. However, most high estimates are unsubstantiated and tend to be associated with assertions connected with the mine's promotion or sale. What is reasonably clear is that during operation by the Sierra Buttes Mining Company, between 1872 and 1902, the mine produced approximately $7 million. Records preceding 1872 and after 1902 are unavailable. Actual total production probably ranges between $10 -$15 million. Ore generally ranged from 0.5 to 1.45 ounces per ton during the mine?s heydays up until the 1890s, although ores were found to be much richer near the surface. Ore values declined to the 0.3-0.4 oz/ton range before the Sierra Buttes Mining Company sold the property. Thereafter, limited exploration allowed subsequent operators to exploit small ore bodies in the 0.4-0.5 oz/ton range. Sulfides, while generally making up a small fraction of the ore, could locally range as high as 30%. Yields from sulfide concentrates could average as much as $309/ton. Reports of the California State Mineralogist as late as 1928 and 1936 concluded that much potential prospective ground remained untested below the final mine workings. An independent mine report conducted in 1936 concluded that the mine did not run out of ore, but its underground workings were impaired by water, which existing pumps could not adequately handle. Thus, it is possible that significant reserves may remain within and below the lowermost workings of the mine. Given the current status of the site as a California State Park, this assumption will likely never be tested.

Comment (Development): In 1893, the Plumas-Eureka earned only $9,000. The ore had become low quality but was plentiful. The Chairman of the SBMC Board told shareholders that continued mining was exceedingly doubtful at these values. By 1894 workings were confined to near the summit of the peak in the area of the old Seventy-Six Mine. Only 30 of the 60 stamps at the Mohawk Mill were dropping, and the workforce had dropped to 130. By 1896 work was still confined to the Seventy-Six ground but as the ore played out, the number of working stamps declined to 15 and the workforce declined to 50 men. In 1896, SBMC was no longer prospecting for new ore bodies and by 1897 the Company was only crushing existing ore at ? capacity and employing 10-30 men. In December, SMNC ceased operations and leased the mine to its former employees. During SBMC's operation, most work was done by hand, air drills not generally in use at that date. Production was labor intensive and ore costs ran an average $4/ton. Thus the company ignored any ore that assayed less than $4/ton. So the company left hundreds of thousands of tons of $3 -$4/ton ore in the old workings. The SBMC operation was considered inefficient in that instead of working from the lowest level up, they developed the top of the hill down. Often ore had to be conveyed distances of 400-1,200 feet through surface tramways and around precipitous hillsides before it reached the mill. Supplies were also expensive, having to be imported from San Francisco or Reno. Between 1897 and 1901, the mine was operated by lessees during the summer months with a workforce of between 12-20 men. In October 1901 only ten stamps were still running. The lessees did not try to find any new ore. Instead they only worked the pillars and sweepings left by the Sierra Buttes Mining Co. By 1902, SBMC decided to sell the mine. The decision was not based on lack of ore, from which they were receiving royalties, but because the majority of corporation members had died and the heirs knew nothing of mining. Rather than investing the 30,000 pounds remaining in SBMC reserve funds to explore for more ore bodies, the remaining stockholders decided to withdraw the funds and sell the properties. In 1905, Rhode Island investors purchased the mine and formed the Johnston Graham Mining Company. The transaction included all 2,500 acres and all the timber and water rights. They operated the mine from 1905-1909, during which time they repaired the mine and installed 20 new stamps. They reopened the Eureka Tunnel and erected the aerial tramway from the upper Seventy-Six workings to the mill. Only small quantities of ore were mined each year. During their operation, cyanidization increased recovery to 96%. A second major fire in the town in 1906, effectively marked the end of Johnsville's growth. Owners were reluctant to rebuild, and rebuilding was piecemeal and slow. In 1909 the mine changed hands again and resumed operations as the Plumas-Eureka Mining Company. 1910 was spent repairing the mill by reconstructing the 20 stamps installed by the previous owner, and adding another 20 stamps for a total of 40. The Eureka tunnel was reopened. At this time, the main tunnel was 5,500 feet long and there were many miles of development work in adits, winzes, stopes, and inclines, 7 to 8 miles of which were considered to be in working shape. Only about $105,000 was produced during this period during which the mine was operated in an inefficient and "haphazard" manner. Nonetheless, in 1912 the Plumas-Eureka was second only to the neighboring Jamison mine in gold output in Plumas County.

Comment (Environment): The Plumas-Eureka Mine is located in the Johnsville Mining District of the Northern Sierra Nevada Mountain Range about 175 miles northeast of San Francisco and between the drainages of the Yuba and Feather Rivers. The mine workings are on the east flank of Eureka Peak in south central Plumas County approximately six miles southwest of the small town of Blairsden and is contained within the Plumas-Eureka State Park. This area of Plumas County is rural and sparsely populated. The larger communities of Portola and Quincy (Plumas County Seat) are located approximately 13 miles northeast and 19 miles northwest respectively. The small community of Johnsville, which sprung up during the 1800s to support the Plumas-Eureka Mine still exists within the park boundary approximately 0.5 mile northeast of the mine and adjacent to Jamison Creek. Jamison Creek runs northeast through Jamison Canyon and separates Eureka Peak from Mt. Washington to the southeast. Topography is dominated by heavily forested and mountainous terrain punctuated by small fertile valleys and much of it sculpted in part by Quaternary glaciation. Several smaller glacial mountain lakes dot the higher elevations including Eureka Lake on the north flank of Eureka Peak. The former mine workings are on the east slope of Eureka Peak which exhibits local relief in excess of 2,400 feet between its peak and Jamison Creek on the adjacent valley floor. Quartz veins punctuate the topography, many of which were found to be gold bearing. With the exception of the valley floors which support black oak, the slopes are locally forested with a mixed conifer forest of ponderosa, sugar, yellow, and red pine; red, white, and douglas fir; and western cedar. In places, barren rock and talus alternate with patches of shrubs that include manzanita, ceanothus, chinquapin, buckthorn, and bitter cherry. Climate is alpine with average winter low temperatures between 22 - 280F and summer highs in the mid 80s. Mean annual precipitation is approximately 40 inches, most of which falls during the winter and spring (November to June). Several mine buildings are maintained as park exhibits. The Park visitors center, which originally served as the miners? bunkhouse, also maintains a mining museum dedicated to the Plumas-Eureka and neighboring mines as well as local flora and fauna. Across the street from the museum stands the Mohawk Stamp Mill, Bushman five- stamp mill, stable, mine office, and the blacksmith shop, all of which have been maintained in a "near-restored" condition. Tours of the buildings and demonstrations are conducted during the summer. The neighboring town of Johnsville, which has several permanent residents, also survives.

Comment (Development): Mining ceased in 1914. Plans were made to start a new tunnel to open up the property at considerable depth below the former workings, however, the company went bankrupt in August 1915. Reorganized as the Plumas-Eureka Corporation, work was resumed in 1916. A raise was started from the face of the 7,300-foot Eureka tunnel, the intention being to crosscut for a distance of 1100 ft and connect with the old Seventy Six workings above. The almost vertical raise was driven 534 feet in quartz porphyry. The raise intersected the Mohawk vein 358 feet south of any point previously worked on this vein so a drift was driven along the Mohawk Flat Floor vein to connect with the old workings. It never reached the intended Seventy-Six workings. During the next 8 years, the property was operated for an average of 2 months/year, and the mill was run for only a few week periods to test ore samples. No new ore bodies were developed. During the war years, the mine was hardly operated at all due to the labor shortage and increased supply prices. In 1925, the mine passed into the hands of trustees in Boston and remained idle for nearly a decade. A new company, Plumas-Eureka Mines, Inc., was formed and in 1934, power shovel mining was carried out on the gravel and vein float on the mountainside. The broken rock was hauled by truck to a screening and washing plant. It is reported that 50 tons of this material yielded 21 ounces of gold, 17 ounces of silver, and 2939 pounds lead. Other reports indicate that approximately 300 cubic yards per day were being exploited at a yield of $0.70/yard. A new 20-stamp mill was started in 1936. The operators also had plans to build a dam at Eureka Lake to raise the water level 30 feet, and by means of tunnels and pipelines to hydraulic the remaining ores and mill the tailings. In 1940 the mine was leased to the Portola Corporation, which opened up the old Eureka and Mammoth Tunnels, but explored no new ground. A new ball mill, jaw crusher, classifier, and flotation cells were installed. A recovery of 95% was claimed on an 8-day run on old tailings. No other information is available on this operation. A Hydraulic Mining Permit was issued to Dodge Construction in May 1940, which hydraulically mined limited slopes on Eureka Peak until 1941. All equipment was removed and sold in 1942, and the California Debris Commission approved the mine's closure. From May - November 1943, the Plumas-Eureka tailings were worked under lease. Sixty-seven tons of tailings were reportedly shipped to a smelter from which 57 ounces of gold, 55 ounces of silver, and 4,141 pounds of lead were recovered. When mining at Plumas-Eureka ceased in 1943, it left behind the most complete mining community in the state. Recognizing the historical value and state of preservation, the State of California established the Plumas-Eureka State Park in 1959. Mineral rights to the deposit were not determined during research for this record.

References

Reference (Deposit): Clark, L. D., 1964, Stratigraphy and structure of part of the Sierra Nevada metamorphic belt, California: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 410, 70 p.

Reference (Deposit): Clark, L. D., 1960, Foothills fault system, western Sierra Nevada, California: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 71, p. 483-496.

Reference (Deposit): Clark, W. B., 1970, Gold districts of California: California Division of Mines and Geology Bulletin 193, p. 82-83.

Reference (Deposit): Crawford, J. J., 1894, Plumas County: California State Mining Bureau 12th Annual Report of the State Mineralogist, p. 219.

Reference (Deposit): Coveney, R. M., Jr., 1981, Gold quartz veins and auriferous granite at the Oriental Mine, Alleghany, California: Economic Geology, v. 76, no. 8, p. 2176-2199.

Reference (Deposit): Crawford, J. J., 1896, Plumas County: California State Mining Bureau 13th Annual Report of the State Mineralogist, p. 302.

Reference (Deposit): Saleeby, J., 1981, Ocean floor accretion and volcanoplutonic arc evolution of the Mesozoic Sierra Nevada, in Ernst, W. G., editor, The geotectonic development of California (Rubey Volume I): Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, p. 132-181.

Reference (Deposit): D'Allura, J. A., 1977, Stratigraphy, structure, petrology, and regional correlations of metamorphosed upper Paleozoic volcanic rocks in portions of Plumas, Sierra, and Nevada counties, California: University of California, Davis, Ph.D dissertation, 338 p.

Reference (Deposit): Day, H. W., 1985, Structure and tectonics of the northern Sierra Nevada: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 96, p. 436-450.

Reference (Deposit): Day, H. W. and others, 1988, Metamorphism and tectonics of the northern Sierra Nevada, in Ernst, W. G., editor, Metamorphism and crustal evolution of the western United States (Rubey Volume VII): Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, p. 738-759.

Reference (Deposit): Silva, S. R. and others, 2000, Devonian Sierra Buttes Formation in the Jamison Lake area: Involvement of ancient continental crust in magma genesis, in Brooks, E. R. and Dida, L.T., editors, Field guide to the geology and tectonics of the northern Sierra Nevada: California Division of Mines and Geology Special Publication 122, p. 16-52.

Reference (Deposit): Schweickert, R. A. and Cowan, D. S., 1975, Early Mesozoic tectonic evolution of the western Sierra Nevada, California: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 86, p. 1329-1336.

Reference (Deposit): Jackson, W. T., 1961, A history of mining in the Plumas-Eureka State Park area: Unpublished report prepared for the State of California, Division of Beaches and Parks, 36 p. (available for reference at the Sacramento Library of the California Geological Survey).

Reference (Deposit): Girty, G. H. and Schweickert, R. A., 1984, The Culbertson Lake allochthon, a newly identified structure within the Shoo Fly Complex, California - Evidence for four phases of deformation and extension of the Antler orogeny to the northern Sierra Nevada: Modern Geology, v. 8, p. 181-198.

Reference (Deposit): Grose, T.L.T. and others, 2000, Geologic map of the Blairsden 15' quadrangle, Plumas County, California, California Division of Mines and Geology Open-File Report 2000-21, scale 1:62,500.

Reference (Deposit): Hamilton, F., 1919, Plumas County: California State Mining Bureau 16th Annual Report of the State Mineralogist, p. 21-27, 155-157.

Reference (Deposit): Hanson, R. E., 1983, Volcanism, plutonism and sedimentation in a late Devonian submarine island-arc setting, northern Sierra Nevada, California: Columbia University, Ph.D dissertation, 345 p.

Reference (Deposit): Harwood, D.S., 1988, Tectonism and metamorphism in the northern Sierra Terrane, northern California, in Ernst, W. G., editor, Metamorphism and crustal evolution of the western United States (Rubey Volume VII): Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, p. 764-788.

Reference (Deposit): Irelan, W., 1888, Plumas County: California State Mining Bureau 8th Annual Report of the State Mineralogist, p. 476-478.

Reference (Deposit): McMath, V. E., 1958, The geology of the Taylorsville area, Plumas County, California: University of California, Los Angeles, Ph.D dissertation, 199 p.

Reference (Deposit): Moores, E. M., 1972, Model for a Jurassic island arc - continental margin collision in California: Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, v. 4, no. 3, p. 202.

Reference (Deposit): Preston, E. B., 1890, Plumas County: California State Mining Bureau 10th Annual Report of the State Mineralogist, p. 482-483.

Reference (Deposit): Preston, E. B., 1892, Plumas County: California State Mining Bureau 11th Annual Report of the State Mineralogist, p. 330.

Reference (Deposit): Averill, C. V., 1928, Plumas County: California Division of Mines 24th Annual Report of the State Mineralogist, p. 261-269, 292-293.

Reference (Deposit): Beard, J. S. and Day, H. W., 1987, The Smartville intrusive complex, Sierra Nevada, California: The core of a rifted volcanic arc: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 99, no. 6, p. 779-791.

Reference (Deposit): Bradley, W. W., 1934, Plumas County: California Journal of Mines and Geology, v. 30, no. 4, p. 304.

Reference (Deposit): Bradley, W. W., 1937, Mineral resources of Plumas County: California Journal of Mines and Geology, v. 33, no. 1, p. 79-89, 118-119.

Reference (Deposit): Brooks, E. R., 2000, Geology of a late Paleozoic island arc in the Northern Sierra terrane, in Brooks, E. R. and Dida, L.T., editors, Field guide to the geology and tectonics of the northern Sierra Nevada: California Division of Mines and Geology Special Publication 122, p. 53-110.

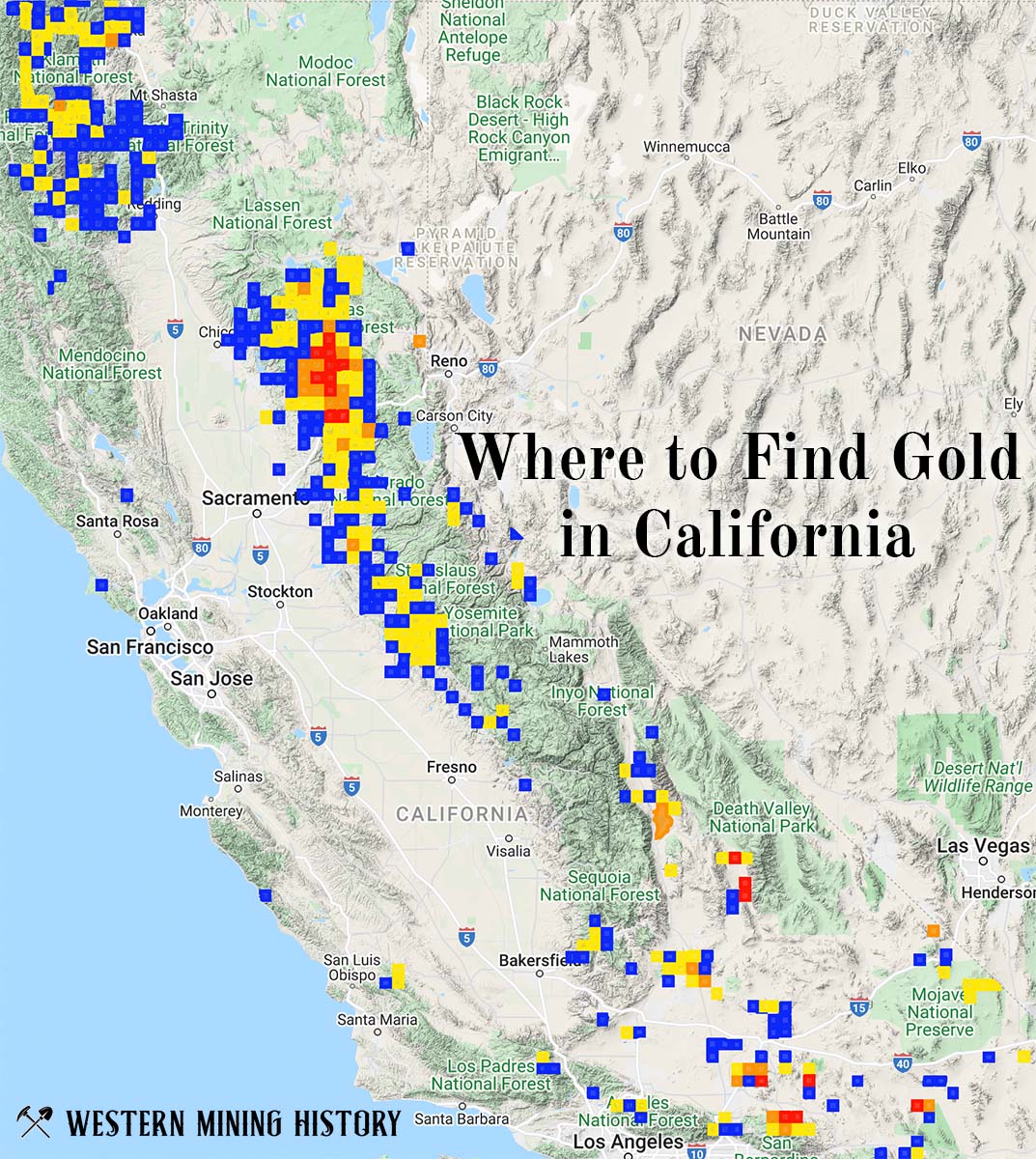

California Gold

"Where to Find Gold in California" looks at the density of modern placer mining claims along with historical gold mining locations and mining district descriptions to determine areas of high gold discovery potential in California. Read more: Where to Find Gold in California.