The Alpha - Omega Mines is a gold mine located in Nevada county, California at an elevation of 3,199 feet.

About the MRDS Data:

All mine locations were obtained from the USGS Mineral Resources Data System. The locations and other information in this database have not been verified for accuracy. It should be assumed that all mines are on private property.

Mine Info

Elevation: 3,199 Feet (975 Meters)

Commodity: Gold

Lat, Long: 39.3368, -120.75790

Map: View on Google Maps

Alpha - Omega Mines MRDS details

Site Name

Primary: Alpha - Omega Mines

Commodity

Primary: Gold

Secondary: Platinum

Secondary: Silver

Location

State: California

County: Nevada

District: Washington District

Land Status

Land ownership: National Forest

Note: the land ownership field only identifies whether the area the mine is in is generally on public lands like Forest Service or BLM land, or if it is in an area that is generally private property. It does not definitively identify property status, nor does it indicate claim status or whether an area is open to prospecting. Always respect private property.

Administrative Organization: Tahoe National Forest (US Forest Service)

Holdings

Not available

Workings

Not available

Ownership

Owner Name: U.S. Forest Service

Production

Not available

Deposit

Record Type: Site

Operation Category: Past Producer

Deposit Type: Stream placer

Operation Type: Surface

Discovery Year: 1850

Years of Production:

Organization:

Significant: Y

Physiography

Not available

Mineral Deposit Model

Model Name: Placer Au-PGE

Orebody

Form: Irregular

Structure

Type: L

Description: Melones Fault Zone

Type: R

Description: Melones Fault Zone, Foresthill Fault

Alterations

Not available

Rocks

Name: Sand and Gravel

Role: Host

Age Type: Host Rock

Age Young: Tertiary

Analytical Data

Not available

Materials

Ore: Gold

Ore: Chlorite

Ore: Epidote

Ore: Amphibole

Ore: Pyrite

Ore: Zircon

Ore: Ilmenite

Ore: Magnetite

Ore: Quartz

Ore: Siderite

Comments

Comment (Workings): Hydraulic Mining Hydraulic mining methods were first applied in 1852 to the Yankee Jims gravels in the Forest Hill District of central Placer County. Its use and methods quickly evolved to where it was applied to most exposed Tertiary gravel deposits. Hydraulic mining involved directing a powerful stream of high pressure water through large nozzles (called "monitors") at the base of a gravel bank, undercutting it and allowing it to collapse. The loosened gravels were then washed through sluice boxes. The remaining tailings were indiscriminately dumped in the nearest available stream or river. Large banks of low-yield gravel could be economically mined this way. In some cases, adits were driven into the exposed face and loaded with explosives to help break down the exposure. One of hydraulic mining's highest costs was in the ditches, flumes, and reservoirs needed to supply sufficient volumes of water at high pressure. A mine might have many miles of ditches as well as dams and reservoirs, flumes, and tunnels. Hydraulic mining flourished for about 30 years until the mid-1880s when the Sawyer Decision essentially brought it to a halt. More specific information on the Apha-Omega workings is contained in the Exploration and Development section.

Comment (Development): While mining in the Washington District began in 1848-1849 as miners recovered considerable gold from placers of the Middle Yuba River, hydraulic mining of the Alpha and Omega deposits commenced in the mid-1850s. The mines were worked extensively until the mid-1880s when the Sawyer Decision put an end to large-scale hydraulic mining in the Sierra Nevada. Prior to that time, the Omega Mine was hydraulicked using three monitors. Water was obtained from a 9-mile flume and company ditches, which provided 5,000 miner's inches from the South Fork of the Yuba River, and another ditch, which brought 1,200 miner's inches from Diamond Creek. Tailings were channeled through a 3,000-foot bedrock tunnel and discharged into Scotchman Creek, which drained into the South Fork of the Yuba River. Later, Chinese miners reworked the old hydraulic tailings. Sometime before 1914, a restraining dam had been constructed in Scotchman Creek to contain the tailings. The Omega gravels were intermittently worked as late as 1914.

Comment (Economic Factors): Jarman (1927) estimated that at Omega, 13 million yards were mined and yielded an average 13-? cents per yard. Lindgren (1911) estimated that 40 million cubic yards remained.

Comment (Deposit): The Alpha and Omega mines produced from Tertiary channel gravels that were part of an important branch of the ancestral Yuba River, which flowed westward to the auriferous gravel deposits at Relief Hill in the North Bloomfield District six miles to the west. The gravels rest directly on basement, into which the ancient river incised its channel. The bottom of the channel lies 1000 feet above the level of the present day South Fork of the Yuba River, which is nearby. Consistent with most Tertiary gravel deposits in neighboring districts, the deposits can be divided lithologically and texturally into lower and upper units. The lower unit, or blue lead of the early miners, rests directly on bedrock and contains the richest ores.

Comment (Geology): Bedrock erosion degraded the rich gold-bearing veins and auriferous schists and slates as the rivers crossed the metamorphic belts of the Sierra Nevada. Upstream of the gold belts on the granitic Sierra Nevada batholith, channels are largely barren, but become progressively richer as they cross the metamorphic belt and the Mother Lode trend. They become especially enriched after crossing the gold-bearing "serpentine belt" (Feather River Peridotite Belt) upstream of many Tertiary placer districts. While the most gold is contained in the lower sand and gravel, the majority of rich material is within only a few feet of bedrock. Generally, in drift mines only these lower gravels were exploited; however, in hydraulic mines the whole gravel bed was washed. Lindgren (1911) estimated that on average, the hydraulic washing of thick gravel banks up to 300 feet, including both basal and upper gravels, yielded approximately $0.10 to $0.40/yard. Upper gravels alone might average $0.02 to $0.10/yard and lower gavels from $0.50 to $15/yard or more. The bulk of the gold in the deposits was derived from gold-bearing quartz veins within the low-grade metamorphic rocks of the Sierra Nevada. Gravels that have the highest gold values contain abundant white quartz vein detritus and clasts of blue-gray siliceous phyllite and slate common to the gold-quartz vein-bearing bedrock of the region. Unusually high gold concentrations have also been documented immediately downstream of eroded qold quartz veins exposed in the scoured bedrock. Most of the gold found in the gravels of the North Bloomfield and Moore's Flat districts is thought to have originated from the famous lode veins of the Alleghany Mining District. The veins in the Nevada City and Grass Valley districts have been proposed as possible sources for the gold in the gravels of the Sailor Flat and Blue Tent diggings. Gold particles tend to be flat or rounded, shiny and rough, and range from fine and coarse gold to nuggets of 100 or more ounces. Large nuggets were especially prevalent in the Alleghany, North Columbia, Downieville, and Sierra City Districts. The gold particles are almost everywhere associated with black sands composed of magnetite, ilmenite, chromite, zircon, garnet, pyrite, and in some places platinum. Fine flour gold is not abundant in any of the Tertiary gravels. Lindgren (1911) and others have suggested that most of the flour gold was swept westward to be deposited in the thick sediments of the Great Valley. Valley Springs Formation After deposition of the Eocene channel gravels, Oligocene-Miocene volcanic activity in the upper Sierra Nevada radically changed drainage patterns and sedimentation. The first of many eruptive rhyolite flows filled the depressions of most river courses covering the Eocene gravels and diverting the rivers. Many tributaries were dammed, but they eventually breached the barriers and carved their own channels within the rhyolite fill. Ensuing intermittent volcanism caused recurrent rhyolite flows to fill and refill the younger channels resulting in a thick sequence of intercalated intervolcanic channel gravels and volcanic flows. In the Scotts Flat District, very little of the Valley Springs Formation remains, having been lost to erosion. Mehrten Formation Volcanism continued through the Oligocene to the Pliocene, with a change from rhyolitic to andesitic composition and a successively greater number of flows. During the Miocene and Pliocene, volcanism was so extensive that thick beds of andesitic tuffs and mudflows of the Mehrten Formation blanketed the Valley Springs. Thicknesses ranged from a few hundred to a few thousand feet. Pleistocene erosion removed much of these deposits, but remnants cap the axes of many existing ridges at mid-elevations.

Comment (Geology): Continued uplift during the Pliocene-early Pleistocene increased gradients allowing the modern drainages to cut through the volcanic mantle and auriferous gravel deposits and deeply into basement. The once-buried Tertiary river gravels were left exposed in outcrops high on the flanks of the modern drainage divides. Structure Most Upper Jurassic and younger basement rocks of the northern Sierra Nevada were metamorphosed and deformed during the Jurassic-Cretaceous Nevadan Orogeny. The dominant northwest-trending structural grain is a result of this period of compressive deformation, which produced thrust faults, major northwest-trending folds, and regional greenschist facies metamorphism. This episode also resulted in intrusions of granitic plutons that formed the Sierra Nevada. Nevadan deformation structures within and between the northern Sierra Nevada lithotectonic blocks are steeply dipping northwesterly trending faults and northwesterly trending folds. These features are best developed in the Eastern, Central, and Feather River Peridotite Belts, where the faults have been collectively described as the "Foothills Fault System" (Clark, 1960). Where the attitude can be determined, most of the bounding faults dip steeply east and display reverse displacement. The regional northwest-trending structural grain is also at approximately right angles to the prevailing direction of stream flow of both the ancient and modern channels. This grain, expressed in the form of foliation and cleavage in the metamorphic bedrock, served as a good trapping mechanism for the gold particles. GEOLOGY OF THE ALPHA AND OMEGA MINES Basement beneath the Alpha and Omega mines consists of slate, schist, and quartzite of the Paleozoic Shoo Fly Complex. The Melones Fault Zone is just west of the Alpha Mine and separates the Shoo Fly Complex from the Feather River Peridotite Belt. Basal Eocene Auriferous Gravels The Alpha and Omega mines produced from Tertiary channel gravels that were part of an important branch of the ancestral Yuba River, which flowed westward to the auriferous gravel deposits at Relief Hill in the North Bloomfield District six miles to the west. The gravels rest directly on basement, into which the ancient river incised its channel. The bottom of the channel lies 1000 feet above the level of the present day South Fork of the Yuba River, which is nearby. Rocks of the Valley Springs and Mehrten Formations, which were originally deposited over the gravels, have been stripped away by erosion exposing the gravels. Consistent with most Tertiary gravel deposits in neighboring districts, the deposits can be divided lithologically and texturally into lower and upper units. The lower unit, or blue lead of the early miners, rests directly on bedrock and contains the richest ores. At the Omega workings, several hundred acres of auriferous gravel were exposed with a maximum exposed thickness of 175 feet. The deposits are composed of 150 feet of lower auriferous gravel covered by 6 feet of clay, which is overlain by another 20 feet of auriferous gravel that carries fine gold. In the lower gravels, the bulk of the material is less than 6 inches in diameter; some large granite boulders rest on bedrock. Compared to most other Tertiary gravel deposits where the finer upper gravels are the thicker unit, the extraordinarily thin unit at the Omega deposits suggests extensive Pliocene and later erosion. Omega gravels were known for their consistent yield of between 13 ? and 23 cents per yard. At the Alpha Workings, about 75 acres of auriferous gravels were preserved. The lower gravels are mainly quartz, quartzite, and hard conglomerate. Some quartz boulders up to 5 feet in diameter rest on bedrock. The gravel banks were 90 feet high including a 20-foot thick clay bed at the top.

Comment (Commodity): Commodity Info: Average values for the undifferentiated gravels at the Omega workings were estimated to be $0.23/cubic yard ($35/oz).

Comment (Commodity): Ore Materials: Native gold - Fine -coarse gold and nuggets (.900 fine)

Comment (Commodity): Gangue Materials: Quartz and metamorphic gravels; accessory minerals - magnetite, ilmenite, zircon, pyrite, amphibole, epidote, chlorite, and siderite

Comment (Geology): REGIONAL SETTING The northern Sierra Nevada is home to numerous important gold deposits. These include the famous lode districts of Johnsville, Alleghany, Sierra City, Grass Valley, and Nevada City as well as the famous placer districts of North Bloomfield, North Columbia, Cherokee, Foresthill, Michigan Bluff, Gold Run, and Dutch Flat. The geological and historical diversity of most of these deposits and specific mine operations are covered in numerous publications produced over the years by the U.S. Bureau of Mines, U.S. Geological Survey, California Division of Mines and Geology (now California Geological Survey), and others. The most recent geologic mapping covering the area is the 1:250,000-scale Chico Quadrangle compiled by Saucedo and Wagner (1992). Stratigraphy The northern Sierra Nevada basement complex has a history of both oceanic and continental margin tectonics recorded in sequences of oceanic, near continental, and continental volcanism. The complex has been divided into four lithotectonic belts: the Western Belt, Central Belt, Feather River Peridotite Belt, and Eastern Belt. The Western Belt is composed of the Smartville Complex, an Upper Jurassic volcanic-arc complex, which consists of basaltic to intermediate pillow flows overlain by pyroclastic and volcanoclastic rock units with diabase, metagabbro, and gabbro-diorite intrusives. The Cretaceous Great Valley sequence overlies the belt to the west. To the east it is bounded by the Big Bend-Wolf Creek Fault Zone. East of the Big Bend-Wolf Creek Fault Zone is the Central Belt, which is in turn bounded to the east by the Goodyears Creek Fault. This belt is structurally and stratigraphically complex and consists of Permian-Triassic argillite, slate, chert, ophiolite, and greenstone of marine origin. The Feather River Peridotite Belt is also fault-bounded, separating the Central Belt from the rocks of the Eastern Belt for almost 95 miles along the northern Sierra Nevada. It consists largely of Devonian-to-Triassic serpentinized peridotite. The Eastern Belt, or Northern Sierra Terrane, is separated from the Feather River Peridotite Belt by the Melones Fault Zone. The Northern Sierra Terrane is primarily composed of siliciclastic marine metasedimentary rocks of the Lower Paleozoic Shoo Fly Complex overlain by Devonian-to-Jurassic metavolcanic rocks. Farther east are Mesozoic granitic rocks of the Sierra Nevada Batholith. The northern Sierra Nevada experienced a long period of Cretaceous to early Tertiary erosion followed by extensive late Oligocene to Pliocene volcanism. The oldest Tertiary deposits are Eocene auriferous gravels deposited by the predecessors of the modern Yuba and American rivers and preserved in paleochannels eroded into basement and on adjacent benches. In contrast to earlier volcanism, Tertiary volcanism was continental, with deposits placed on top of the eroded basement rocks, channel deposits, and Mesozoic intrusives. Two regionally important units are the Valley Springs and Mehrten Formations. The Oligocene-Miocene Valley Springs Formation is a widespread unit of intercalated rhyolite tuffs and intervolcanic channel gravels that blanketed and preserved the basal gravels in the valley bottoms. The younger Miocene-Pliocene Mehrten Formation consists largely of andesitic mudflows, which regionally blanketed all but the highest peaks and marked the end of Tertiary volcanism. Pliocene-Pleistocene uplift of the Sierra Nevada caused the modern drainages to erode through the volcanic Valley Springs-Mehrten sequences and carve deep river gorges into the underlying basement rocks. During this process, the modern rivers became charged with placer-gold deposits from both newly eroded basement rocks and from the reconcentration of the eroded Tertiary placers. The discovery of these modern Quaternary placers in the American River at Sutter's Mill sparked the California Gold Rush.

Comment (Identification): The Alpha and Omega mines are the two primary hydraulic placer mines that comprise the Washington mining district in east-central Nevada County. They are located approximately 18 miles northeast of Nevada City. The Alpha "Diggings" produced over $2 million. Production figures are unavailable for the Omega diggings, a mile to the east.

Comment (Location): Location selected for latitude and longitude is the approximate center of the larger ?Omega Diggings? on the USGS 7-1/2 minute Washington quadrangle.

Comment (Geology): Tertiary Channel Gravels It has been estimated that 40 percent of California's gold production has come from placer deposits along the western Sierra Nevada (Clark, 1966). These placer deposits are divisible into Tertiary deposits preserved on the interstream ridges, and Quaternary deposits associated with present streams. Lindgren (1911) estimated that approximately $507 million (at $35.00/oz.) was produced from the Tertiary gravels. Almost all Tertiary gravel deposits can be divided into coarse basal Eocene gravels resting on basement, and overlying upper or "intervolcanic" gravels. While the gravels differ texturally, compositionally, and in gold values, no distinct contact exists between the two. The boundary is usually placed where pebble and cobble beds are succeeded by overlying pebble, sand, and clay beds. Lower gravels contain most of the gold and rest on eroded bedrock that is usually smooth, grooved, and polished. Where bedrock is granitic, it is characterized by a smooth and polished surface. Where bedrock is slate, phyllite, or similar metamorphic rock, rock cleavage, joints, and fractures acted as natural riffles to trap fine to coarse gold. In many cases, miners would excavate several feet into bedrock to recover the trapped gold. The lower gravels, or "blue lead," of the early miners are well-cemented and characterized by cobbles to boulders of bluish gray - black slates and phyllites, weathered igneous rocks and quartz. Boulders may range upwards of 10 feet in diameter. In many deposits, disseminated pyrite and pyritic pebble coatings are common in the lower blue lead gravels. Adjacent to the bedrock channels, broad gently sloping benches received shallow but extensive accumulations of auriferous overbank gravels sometimes 1-2 miles wide. The lower unit is also compositionally immature relative to the upper gravel unit as evidenced by their heavy mineral suites. Chlorite, amphibole, and epidote are common constituents in the basal gravels, but are conspicuously absent in upper gravels. The upper gravels compose the bulk of most deposits, with a maximum measured thickness of 400 feet in the North Columbia District. These gravels carry much lower gold values (rarely more than a few cents per cubic yard) than the deeper sands and are often barren. Upper gravels are finer grained, with clasts seldom larger than cobble size, and contain abundant silt and clay interbeds. Cross-bedding and cut-and-fill sedimentary structures are abundant as well as pronounced bedding and relatively fair to good sorting. Compositionally they are much more mature, with quartz prevailing, and more stable heavy mineral components consisting almost exclusively of zircon, illmenite, and magnetite. Oxidation is common and often imparts a reddish hue to the gravels. During the Cretaceous, the Sierra Nevada was eroded and its sediments transported westward by river systems to a Cretaceous marine basin. By the Eocene, low gradients and a high sediment load allowed the valleys to accumulate thick gravel deposits as the drainages meandered over flood plains up to several miles wide developed on the bedrock surface. The major rivers were similar in location, direction of flow, and drainage area to the modern Yuba, American, Mokelumne, Calaveras, Stanislaus, and Tuolumne Rivers. Their auriferous gravels deposits are scattered throughout a belt 40 - 50 miles wide and 150 miles long from Plumas County to Tuolumne County. In the northern counties, continuous lengths of the channels can be traced for as much as 10 miles with interpolated lengths of over 30 miles. The ancient Yuba River was the largest and trended southwest from headwaters in Plumas County. Its gravels are responsible for the placer deposits in the North Bloomfield, San Juan Ridge/North Columbia, Moore's Flat, and French Corral districts. Tributaries to the ancestral Yuba River were responsible for most of the other auriferous gravels in Nevada County.

References

Reference (Deposit): Clark, L. D., 1960, Foothills fault system, western Sierra Nevada, California: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 71, p. 483-496.

Reference (Deposit): Clark, W.B., 1966, Gold, in Mineral resources of California: California Division of Mines and Geology Bulletin 191, p. 179-185.

Reference (Deposit): Clark, W.B., 1970, Gold districts of California: California Division of Mines and Geology Bulletin 193, p. 128.

Reference (Deposit): Jarman, A, 1927, Omega Mine: California State Mining Bureau Report 23, p. 112-113.

Reference (Deposit): Lindgren, W., 1900, Colfax folio: U.S. Geological Survey Atlas of the U.S., Folio 66, 10 p.

Reference (Deposit): Lindgren, W., 1911, Tertiary gravels of the Sierra Nevada: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 73, p. 139-141.

Reference (Deposit): MacBoyle, E., 1919, Nevada County, Washington Mining District: California State Mining Bureau Report 16, p. 59-63.

Reference (Deposit): Saucedo, G. J. and Wagner, D. L., 1992, Geologic map of the Chico Quadrangle: California Division of Mines and Geology Regional Map Series Map No. 7A, scale 1:250,000.

Reference (Deposit): Yeend, W.E., 1974, Gold-bearing gravel of the ancestral Yuba River, Sierra Nevada, California: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 772, 44 p.

Reference (Deposit): Additional information on the Alpha-Omega mines is contained in File No. 339-5934 (CGS Mineral Resources Files, Sacramento).

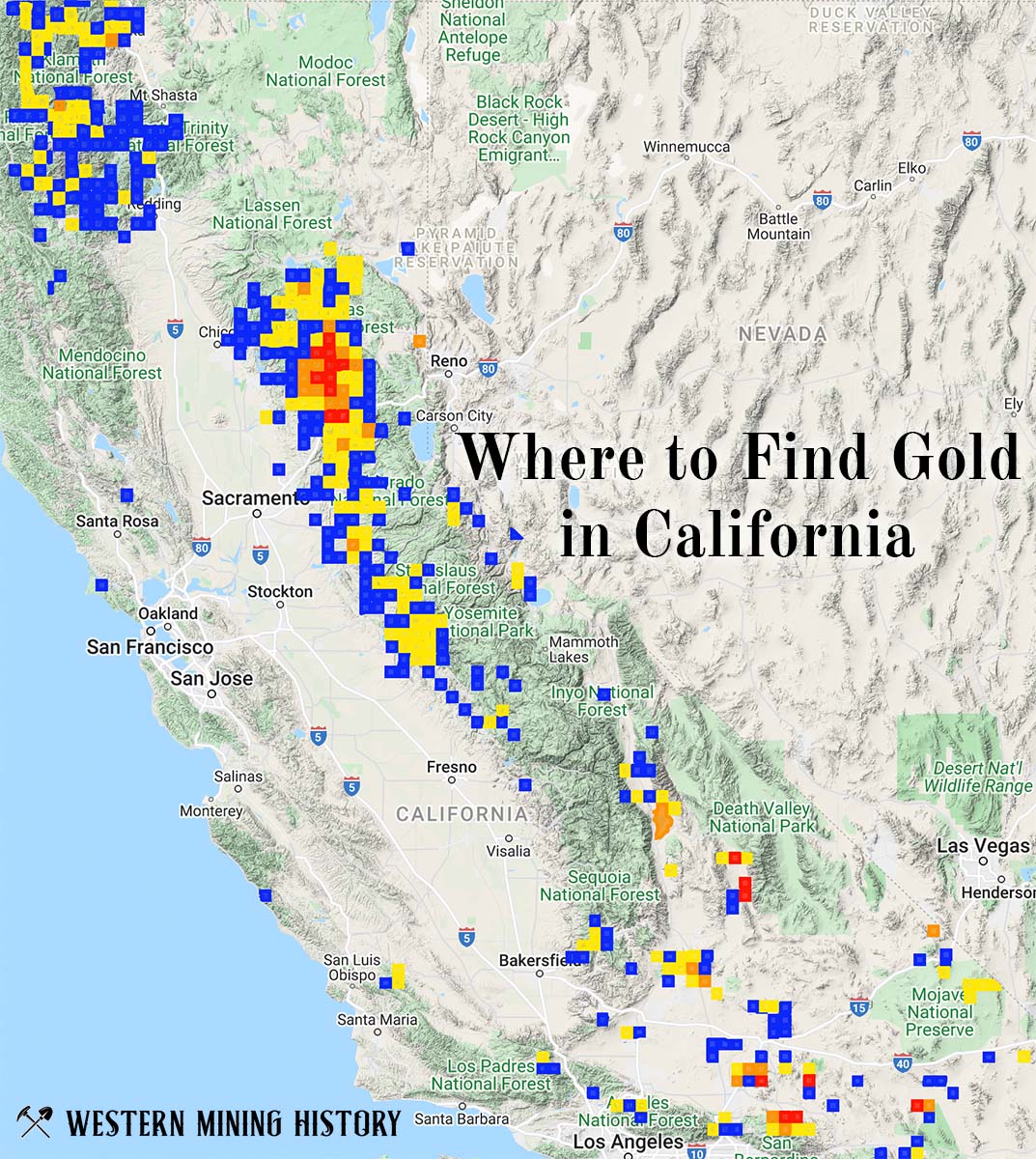

California Gold

"Where to Find Gold in California" looks at the density of modern placer mining claims along with historical gold mining locations and mining district descriptions to determine areas of high gold discovery potential in California. Read more: Where to Find Gold in California.