Nome History

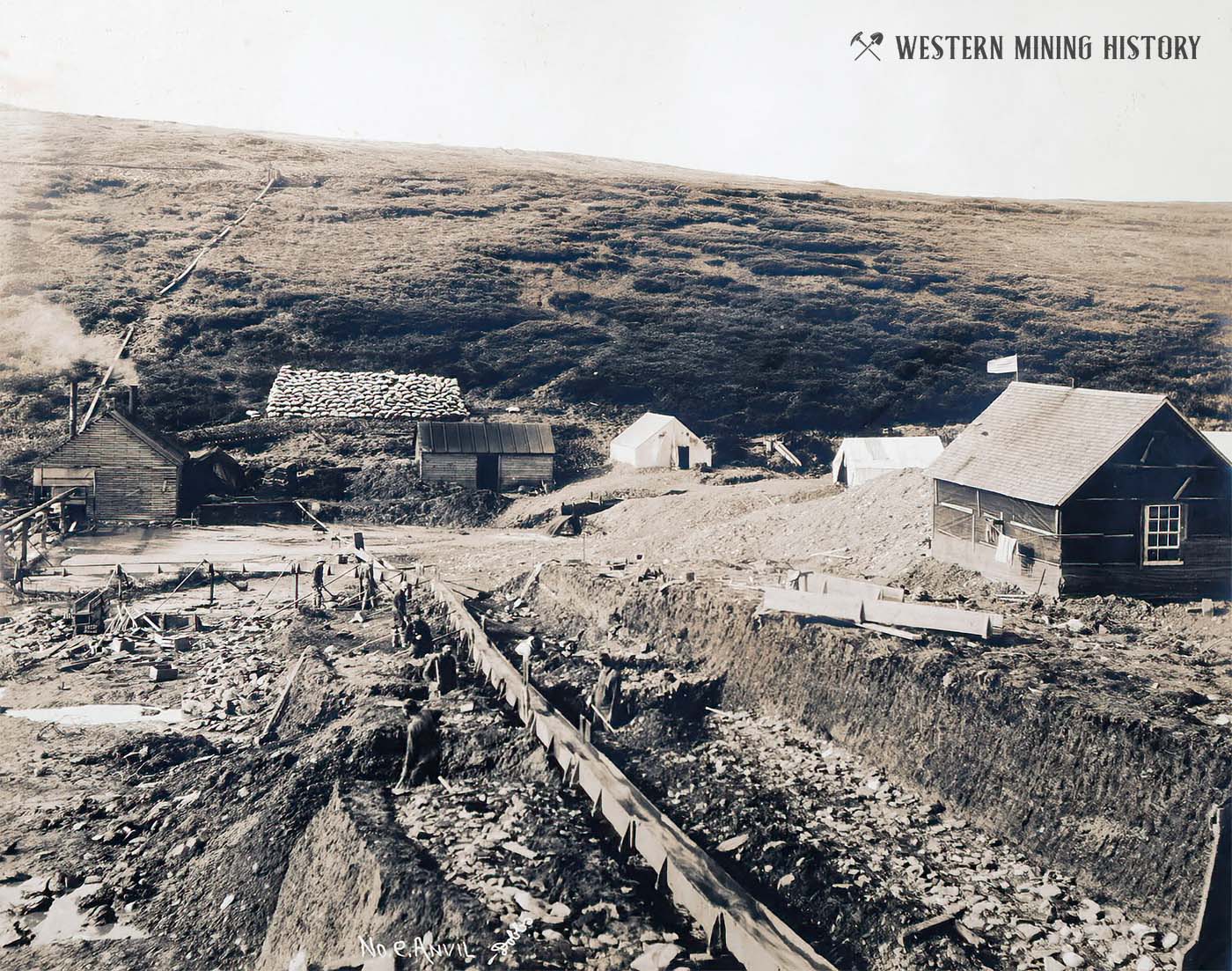

Prospectors discovered gold on Anvil Creek in 1898. Most sources credit the discovery to "Three Lucky Swedes", but a more detailed account published in the Engineering and Mining Journal indicates they were not the first to discover gold in the area. The full account is included below.

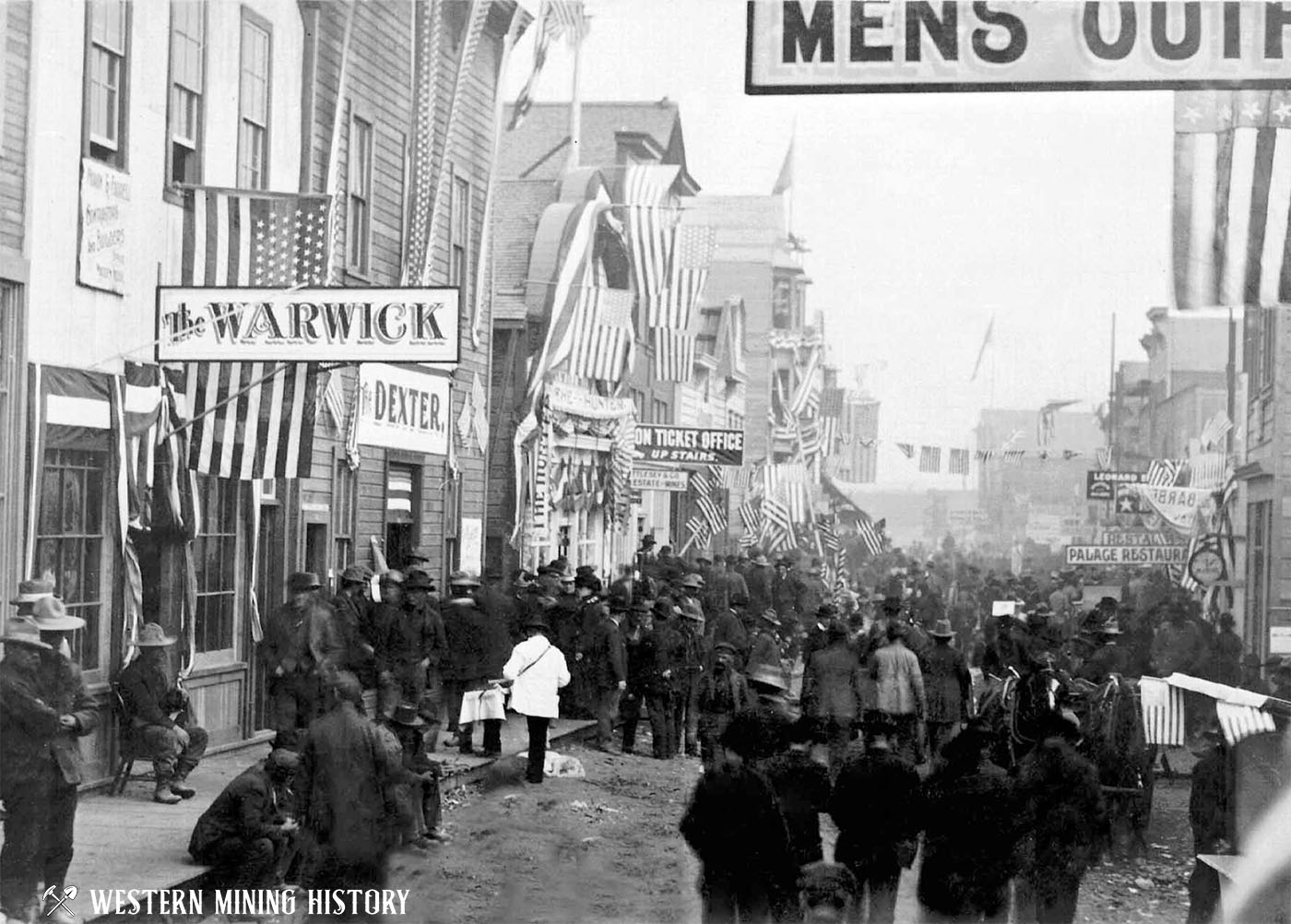

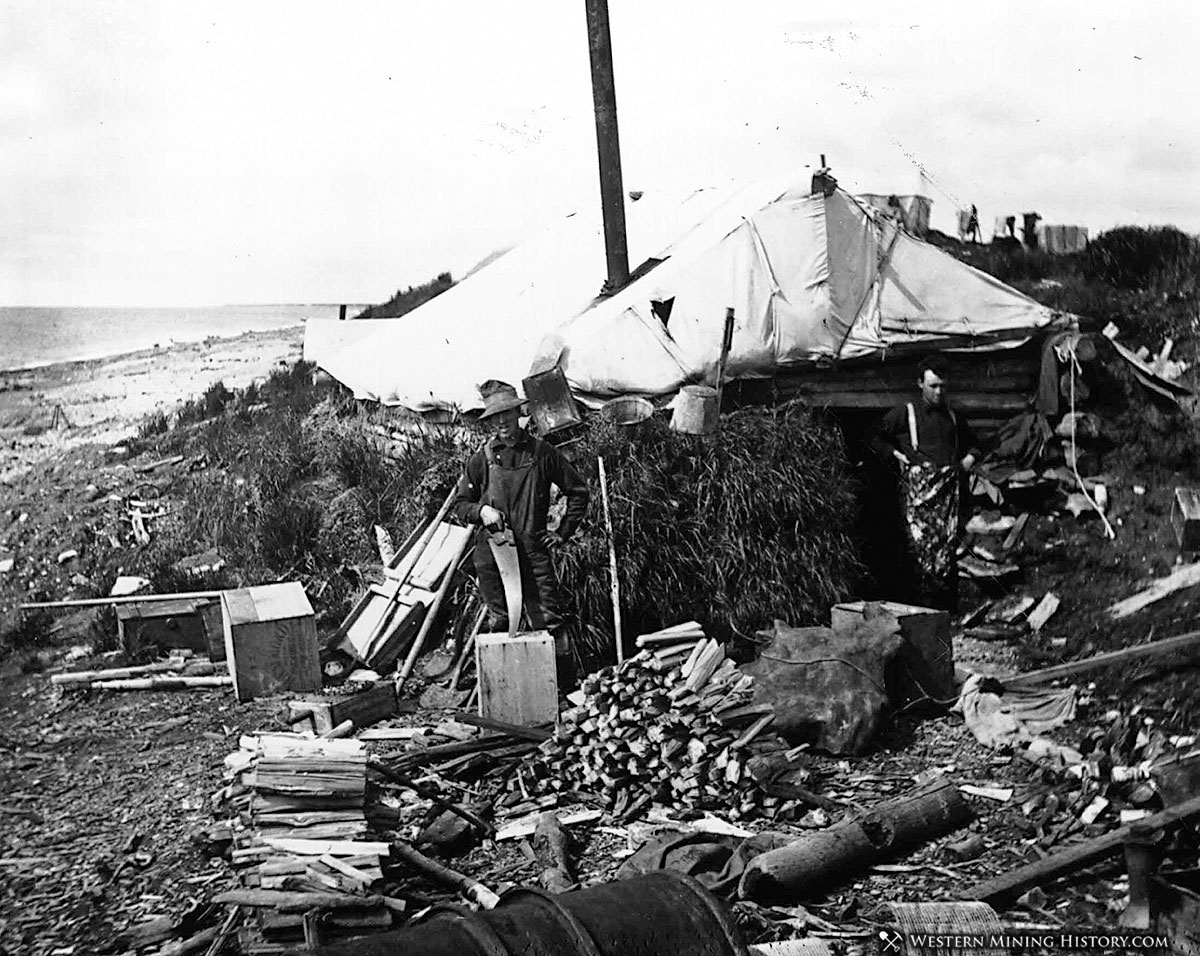

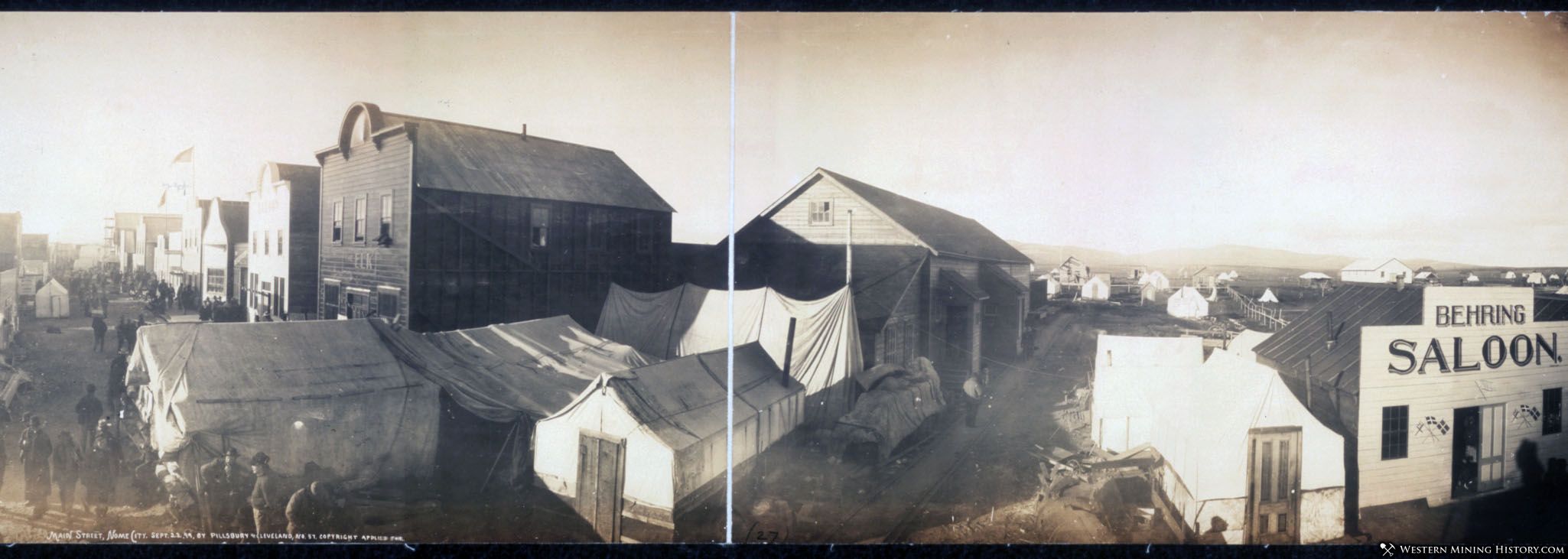

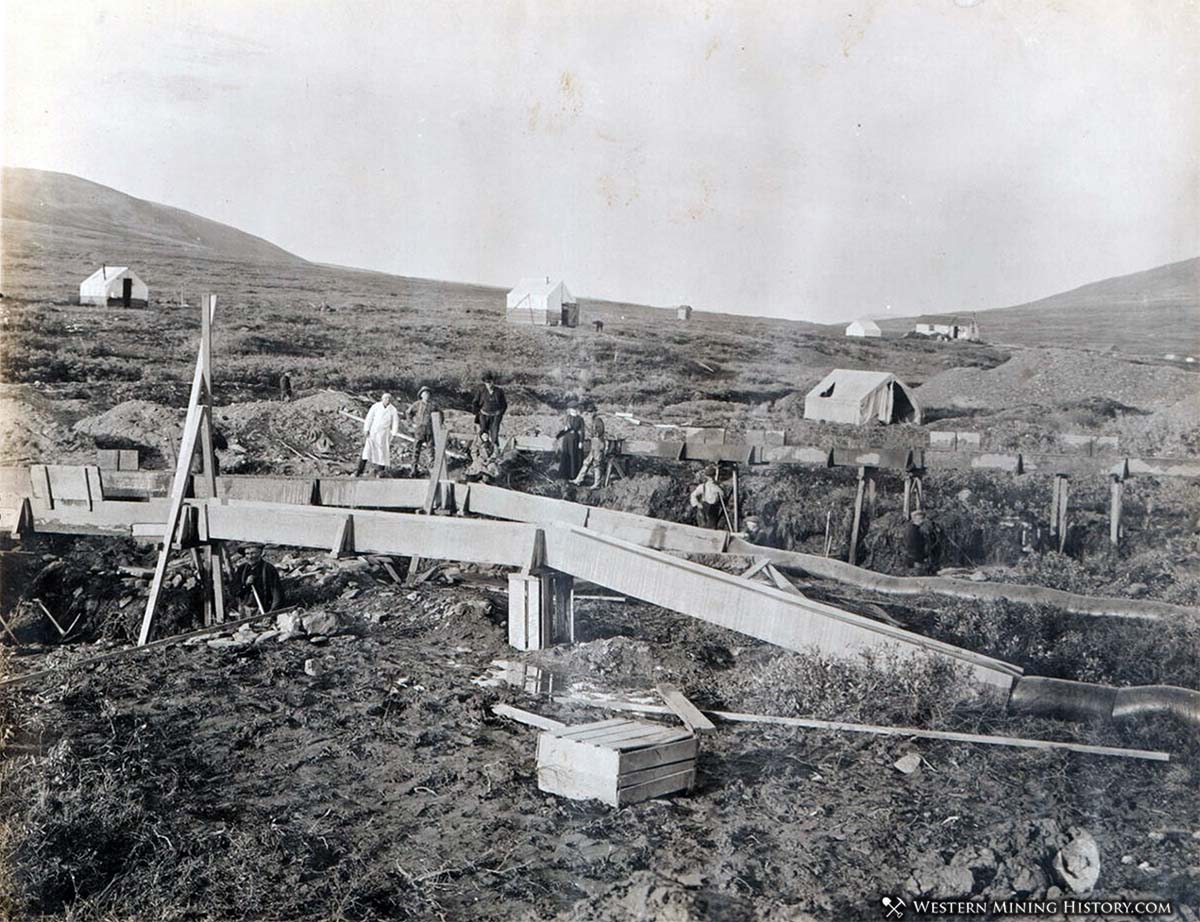

It was these "Three Swedes" however that staked the first claims and started the excitement that resulted in a gold rush early 1899. The original settlement was called Anvil City, and it reportedly had 10,000 people living there the first year, most of them in canvas tents. Once ships started arriving from the lower 48, wood buildings were built as supplies became available.

The 1968 USGS publications Principle Gold Producing Districts of the United States provides a good description of rush to Nome:

Soon after the discoveries of placer gold at Council in 1897, placer gold was discovered on the Snake River near Nome and a short while later on Anvil Creek, Snow Gulch, Glacier Creek, and other streams. Miners streamed into the area from Golovnin Bay, and the Nome district was formed in October 1898. A great rush to the new district took place in 1899 and a still greater one in 1900. The new town was bursting, and the known placer grounds could not accommodate all those who sought gold.

The unrest thus created led to claim jumping and general lawlessness which taxed the small military garrison to the utmost. With the discovery of rich beach placers in the district, this unhealthy situation was relieved somewhat in that a large new area was available for prospecting and the miners were diverted to gold mining instead of preying upon one another. After 1900, the population stabilized somewhat and with additional discoveries of deep gravels and buried beach placers, the district settled down to a long period of economic stability and orderly growth.

Production of the district from 1897 through 1959 was about 3,606,000 ounces of gold, almost all production was from placers. Data are lacking for 1931-46, so that the total given is a minimum. Cobb (1962) reported small but undisclosed production from scattered lode claims in the district. The Nome district, one of the major producers of Alaska, was active in 1959.

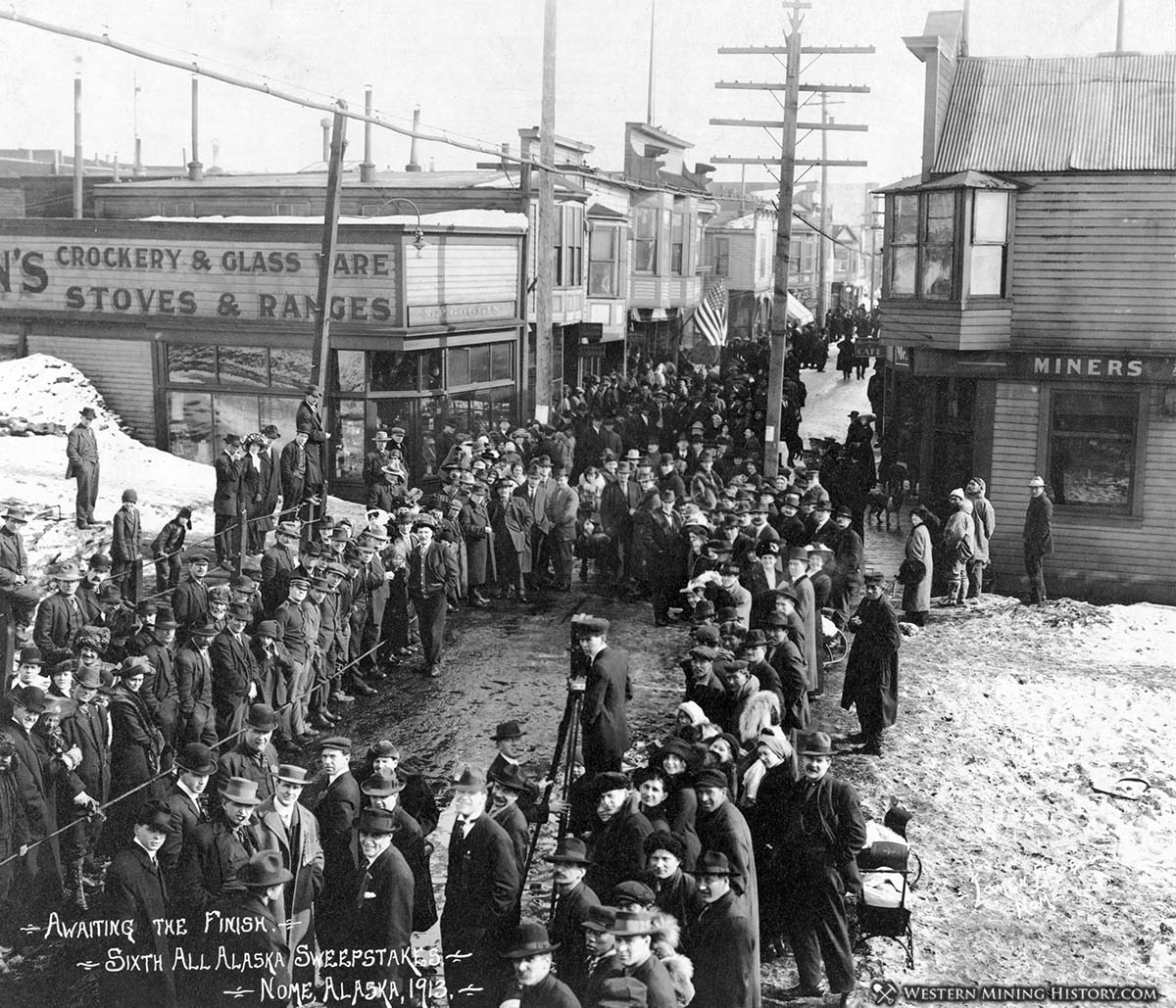

Nome became Alaska's largest city for many years. The 1900 census counted 12,488 residents, and some estimates put the population at around 20,000 during the first decade of the 1900s.

By 1910 the rush was over, and that year the census recorded just 2,600 inhabitants. Although Nome was a substantial city with numerous commercial buildings, a series of fire and severe storms has destroyed most of the historic buildings.

Today, Nome is an active community with several thousand residents. Gold mining continues to be an important economic activity to this day.

Discovery of Gold

A January 1900 edition of The Engineering and Mining Journal included a good article on the early history of Nome. This is the text from that article.

Some Notes on Nome, Alaska

Written for the Engineering and Mining Journal by Paul F. Travers.

Nome, Alaska, on the Behring Sea, 120 miles north of St. Michael and an equal distance southeast from Cape Yorke, is the new Eldorado. The wealth that this district is expected to yield this year has been estimated at various amounts, ranging from $5,000,000 up. The total will certainly be very large. This new field was only discovered in the fall of 1898 and by accident. Many stories are in circulation, but the true facts of the case are as here given.

Two Laplanders, working as reindeer herders for the Government station at Port Clarence, took it into their heads to go to St. Michael, and as they were deserters they had to travel secretly; so with what preparation they could conveniently make, they started overland. After they got down as far as Cape Rodney they accepted shelter with some Esquimaux, and noticing the crude golden ornaments, made from nuggets, some of the women were wearing, made inquiry concerning the same and were told that they were picked up on the coast.

These two men then determined to prospect the country, with the hope of securing some of the coveted metal, and after spending a few days at the Esquimaux camp, where they were treated with all hospitality by these simple people, they worked away down to the place where the city of Nome now stands. There they discovered and located the claims on a creek, which they named Anvil Creek on account of a peculiar rock, shaped exactly like a blacksmith's anvil, which is at the extreme southerly point of the creek and serves as a distinctive landmark, which can be recognizable from a great distance.

The men scratched around a little, satisfying themselves that they had a pretty good thing, and started down to Golofnin Bay to the then nearest recorder to register. Passing Dexters, in the Bonanza District, they exchanged some dust for provisions and continued on to Golofnin Bay. They made mention of their discovery to the few miners there and caused much comment. The miners, however, took no stock in it, for they decided to remain on the claims they were then working, as the results were quite satisfactory, in preference to going on a wild goose chase.

As the winter was coming on they decided not to take any chances on having the water freeze on them before they had their paydirt washed. However, one man became interested in the story-a Mr. Huetzberg, Swedish missionary to the Esquimaux—and he outfitted three men, Lindbloom and two others, and sent them up to verify the stories, if possible. They went off rather reluctantly, and not being fortunate right away, two of them deserted Lindbloom. He persevered and found the place designated, also proving the authenticity of the strike.

Determining on some certain way to mark the route, he returned to Golofnin Bay and there secured the services of two others, Borjonsen and Linderberg. They started back and staked claims for themselves, their friends and everybody else they could think of. Then they went over to St. Michael and swore out citizens' papers. This originated the stampede which depopulated the town. All the big transportation companies, outfitting their own employees, and securing every available party, dispatched them on the trail.

Before the middle of winter there was hardly a foot of ground free of stakes; every creek, gulch and bench was measured off and staked, and a recorder's office was established on the shore. The place was named Anvil City, but was afterward called Nome. There were then 1,250 claims staked out by power of attorney, and from what I saw on the spot I believe that 1,200 of the number are fictitious.

These men, constituting a miners' meeting, enacted and passed laws regulating the bounding of the district, making it 25 miles square, beginning at Cape Nome, or point of contact with the Bonanza District, 12 miles below Nome City, and following the coast west to Penny River. They called it the Cape Nome Mining District. They also passed a resolution fixing the recorder's fee at $2.50, excepting in the case of power of attorney claim, in which it was to be $25. Of this fee $22.50 was to be contributed to a hospital fund.

The size of a claim is 1,320 by 660 ft., or an area of 20 acres.

The meeting also regulated the water rights and virtually settled everything to the entire satisfaction of the original seven men. They also elected one of their number recorder, a Swede named Kittlesen, who has large holdings in these claims.

This was the state of affairs when I reached there last spring. There were then only three houses and some 50 tents squatted on the beach in the snow. One cannot imagine a more desolate, dreary outlook than that which presented itself. Here was a vast expanse of country, mountainous, but utterly devoid of timber or vegetation, covered with ice and snow; certainly anything but an inviting prospect to the tenderfoot.

Comparatively few will succeed in this country, for not many are physically capable of enduring the hardships attending this work. Practically it is always winter at Nome. It is wet and foggy at all times, and to go tramping over the country in the slush of melting snow, with never a dry spot to rest on, is anything but pleasant or healthy. Even in the lower country prospecting is no mean undertaking. At Nome the steamers land you direct from Seattle, but after reaching the beach in a small boat—which in itself is a hazardous undertaking, there being no wharfage facilities—the newcomer must look out for himself.

Before starting out a prospector ought to learn all he can. A week passed in the beginning, getting other people's views, will be well spent. Above all, even the old miner should not be pretentious enough to think that he knows it all. No matter how long he has mined, or where, he will find the conditions at Nome entirely different. Ordinary common sense will further his interests better than a life time spent in a stamp mill or cyanide plant.

About the middle of June the beach and foothills will be free of snow; then it is time to start for the interior. There is nothing left to locate upon nearer than 20 miles from the coast. Every creek and gulch is staked from top to bottom and all benches and side-hills were eagerly sought for last summer. The beach is free for everyone, as the Government reserves it and will not grant a location. It will, however, recognize squatter rights and protect miners while they work.

The gold is about evenly distributed in this beach sand for a distance of 100 miles-possibly further and will pay on an average $20 a day to a man with a rocker. If a miner is intent upon going to Alaska, and has $1,000, he might bring an engine, centrifugal pump and vanner, and he will be satisfied. He should not forget to have oil burners in the boiler and bring the fuel with him. An oil engine ought to be better still. He must take no chances as to buying or duplicating what he wants. If he does he may have a useless piece of machinery on his hands.

The rush of people to Nome this year will be very large. Some will profit while others will be stranded unless they have a trade. Mechanics will command good salaries, while competition will cheapen the cost of living.

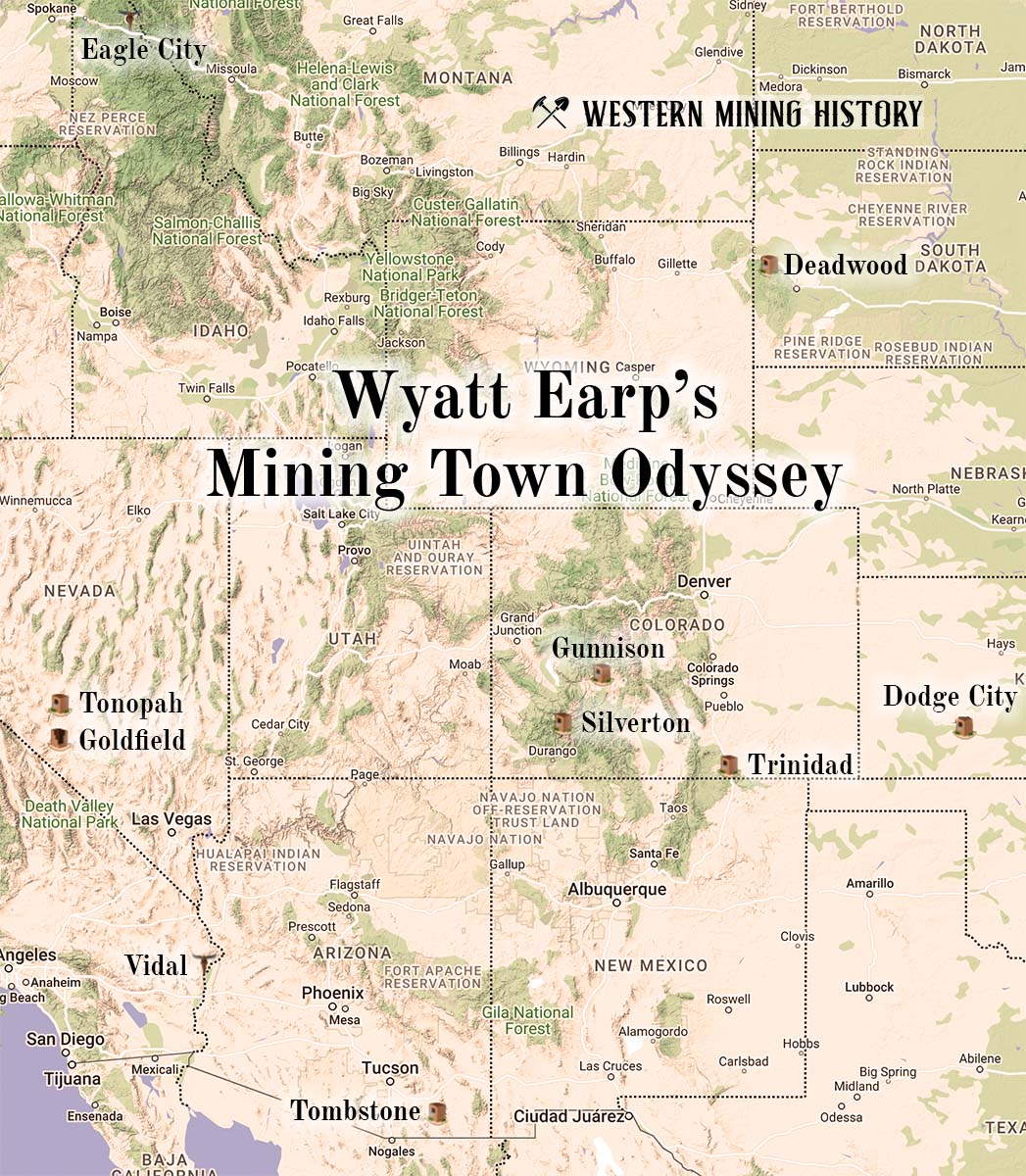

Wyatt Earp: A Mining Town Odyssey

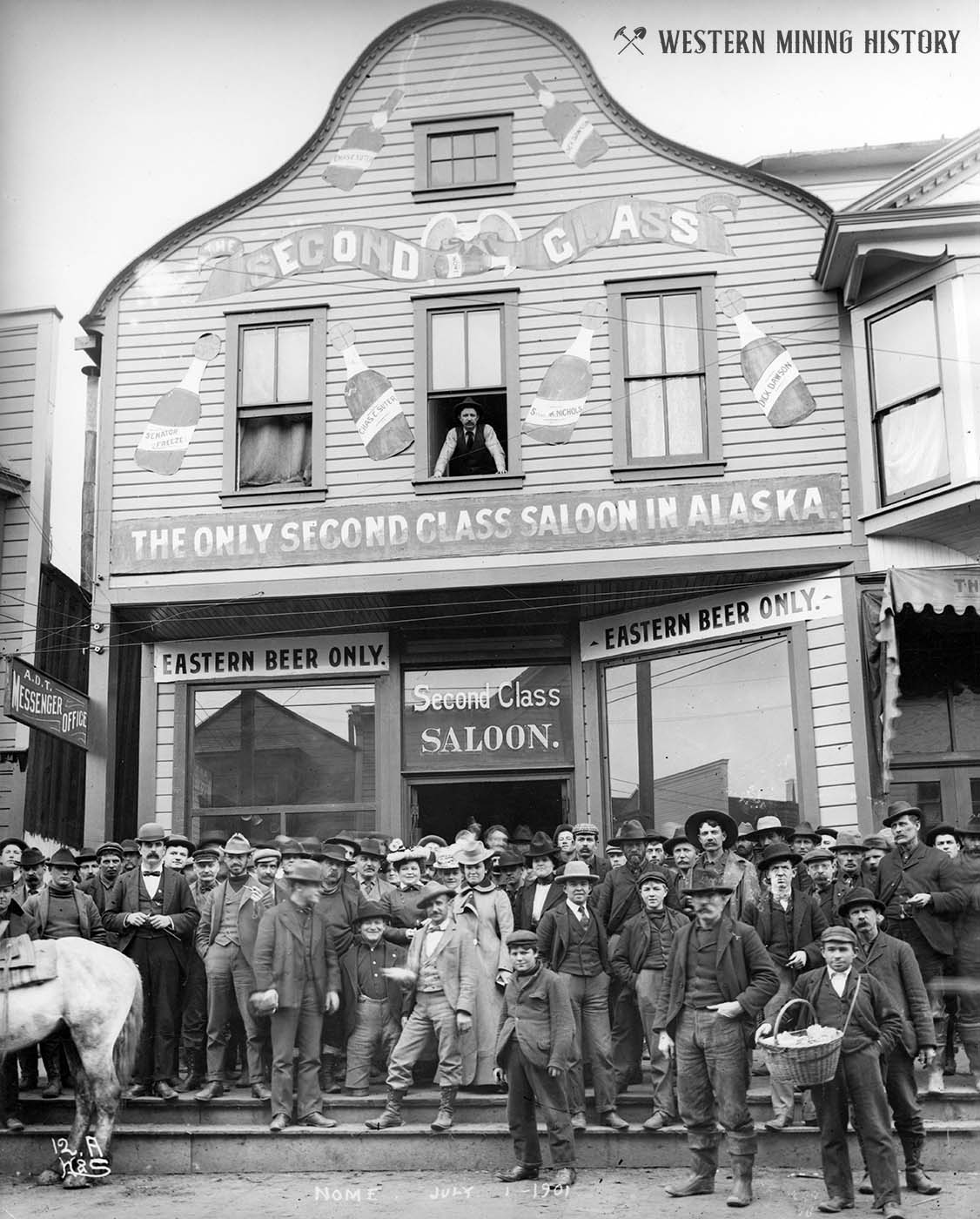

Wyatt Earp spent most of his adult life moving between numerous gold rushes and mining excitements. At Nome, he earned a small fortune as a saloon owner, although after returning to the states he quickly squandered the money and was back to the life of prospector and gunman.

In 1905 a newspaper described his wanderlust: "wherever was a new gold camp, a new oil field, a new place in which money was plentiful, there could be found Wyatt Earp, quiet, careful, but deadly in his own defense." Wyatt Earp: A Mining Town Odyssey