Charleston History

This page is for both Charleston, and Millville across the river.

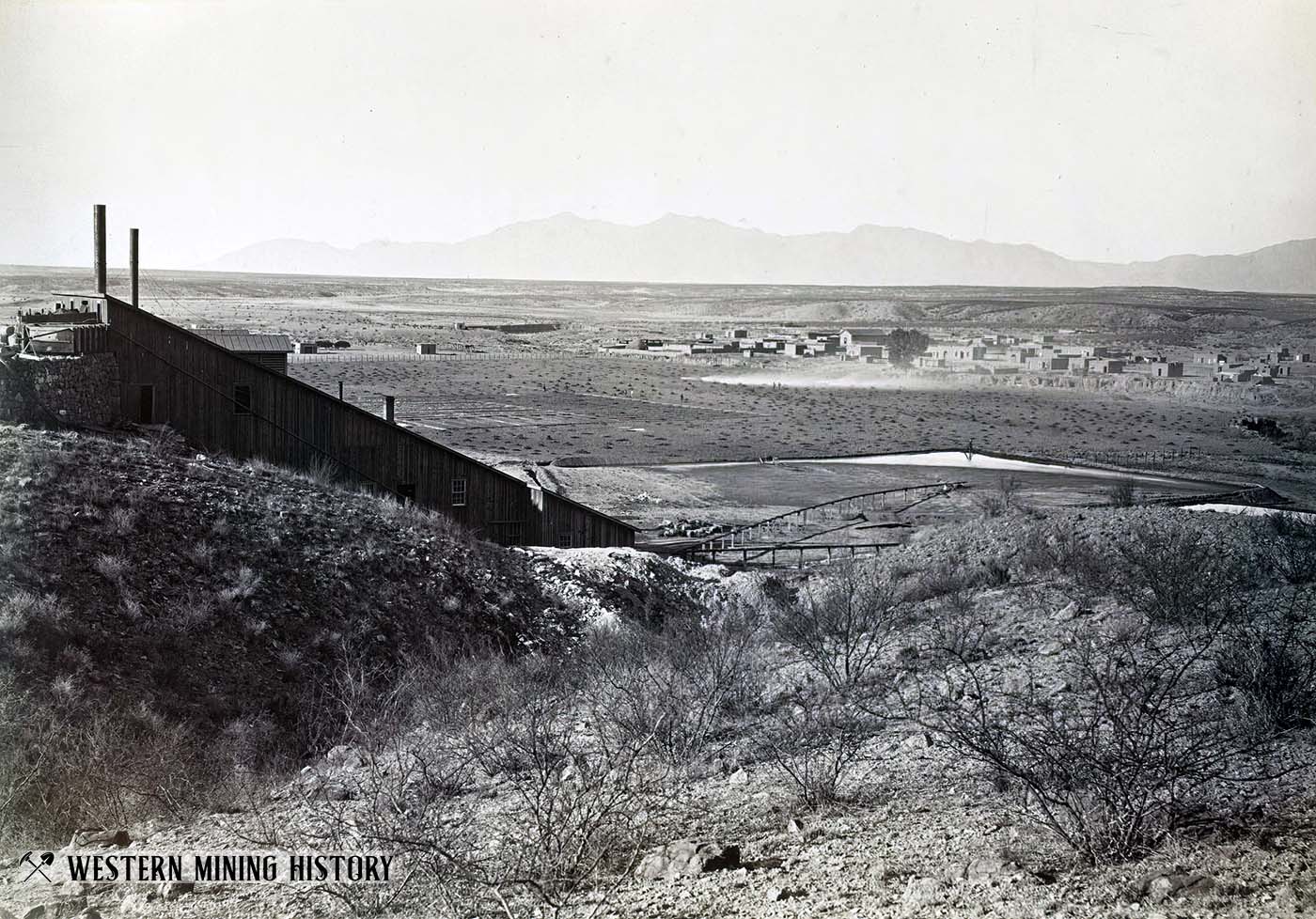

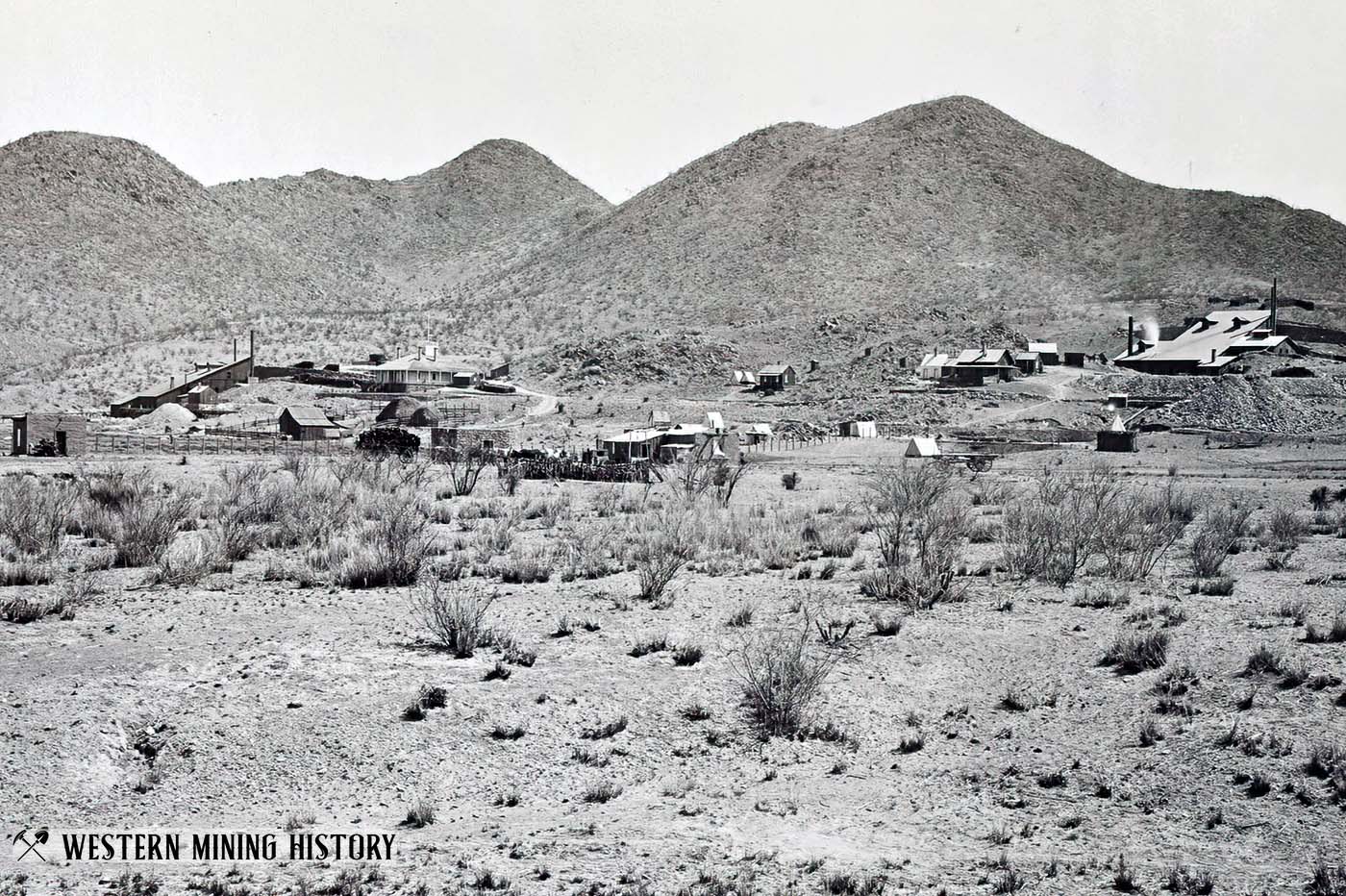

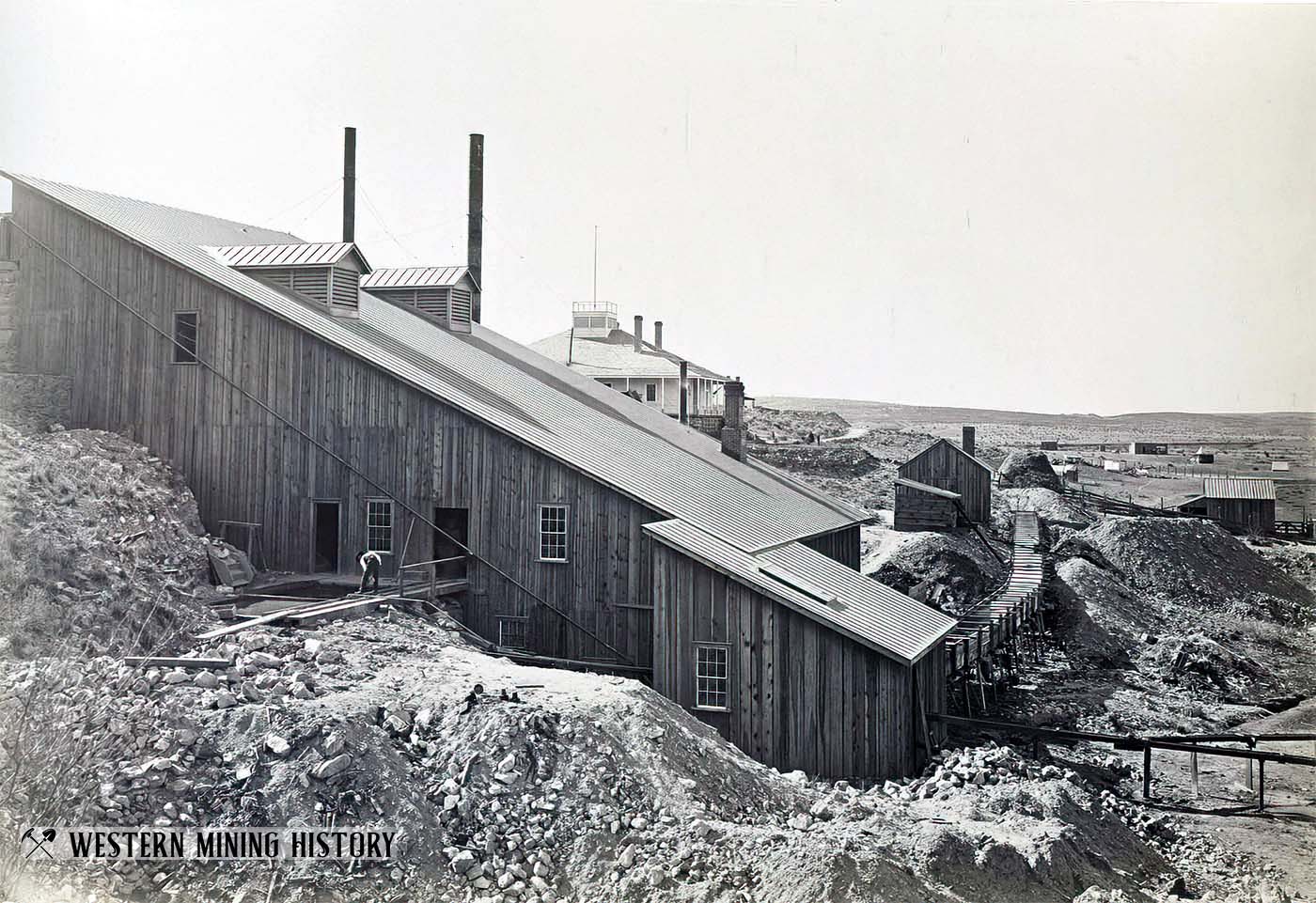

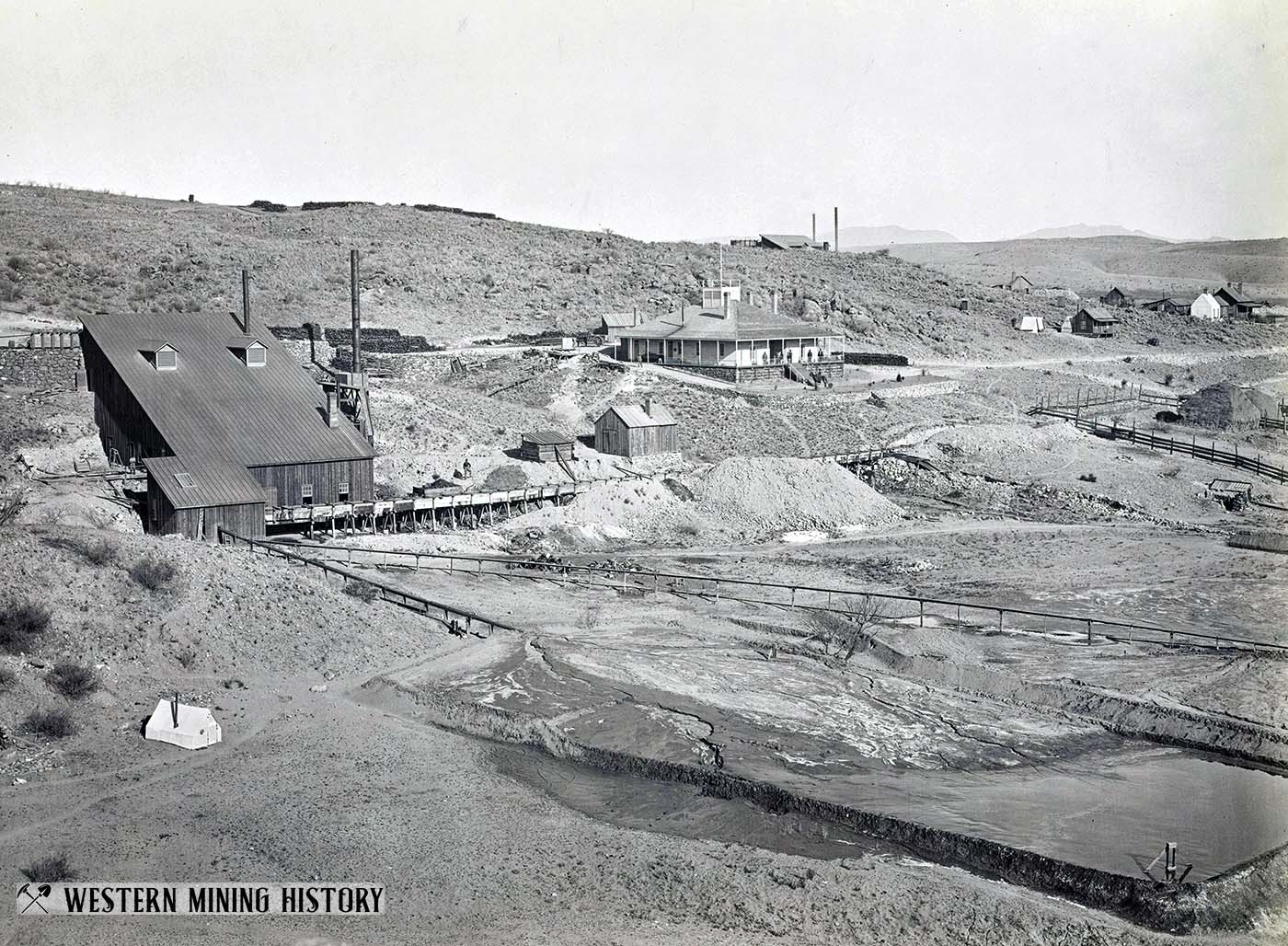

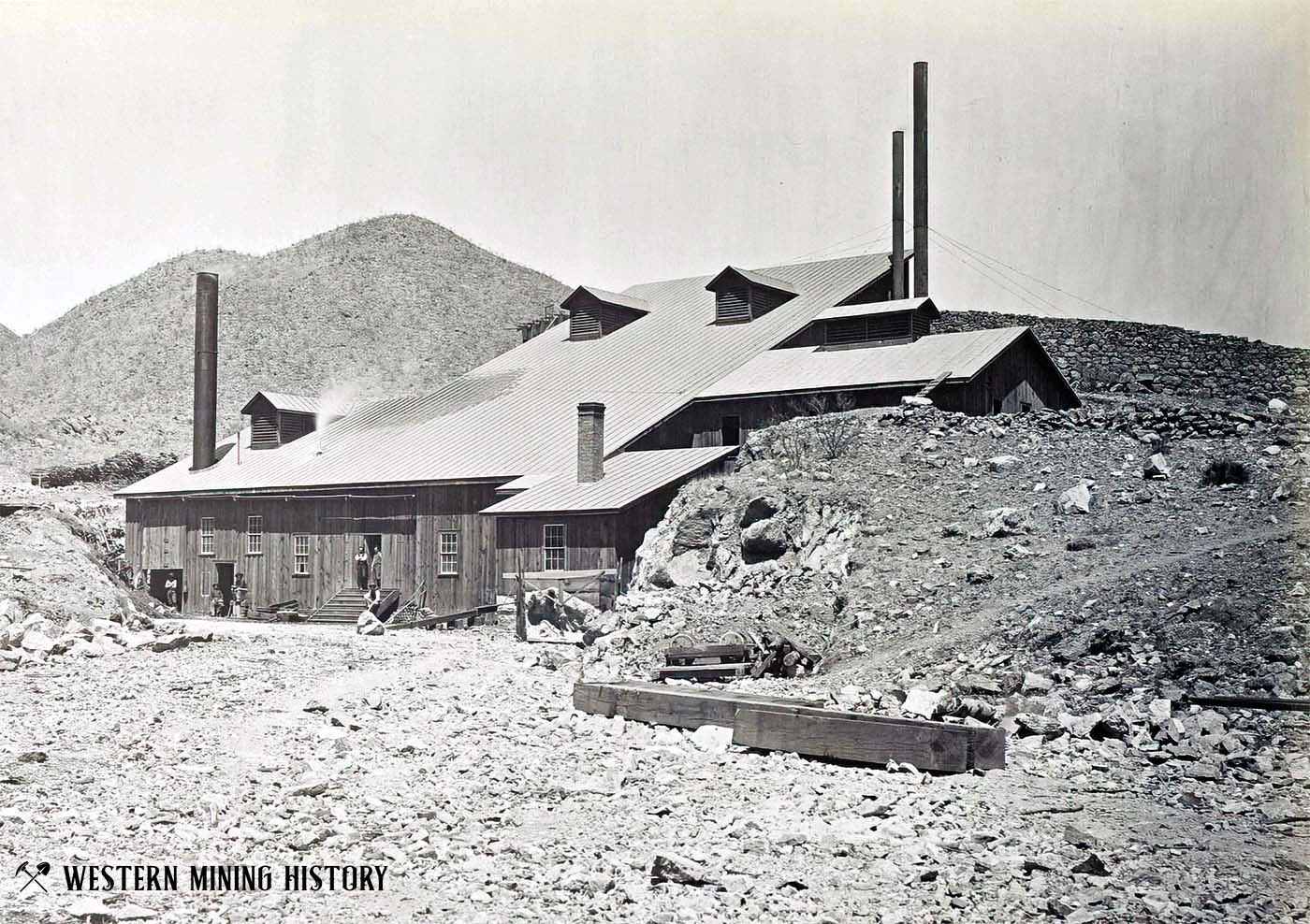

Millville was established in the late 1870's to process ores from the silver mines of Tombstone. The Tombstone area lacked the water needed to run mills, so two mills were built approximately nine miles away on the San Pedro River.

While Millville was named for its primary function as a milling location, Charleston took its name from its original postmaster, Charles D. Handy.

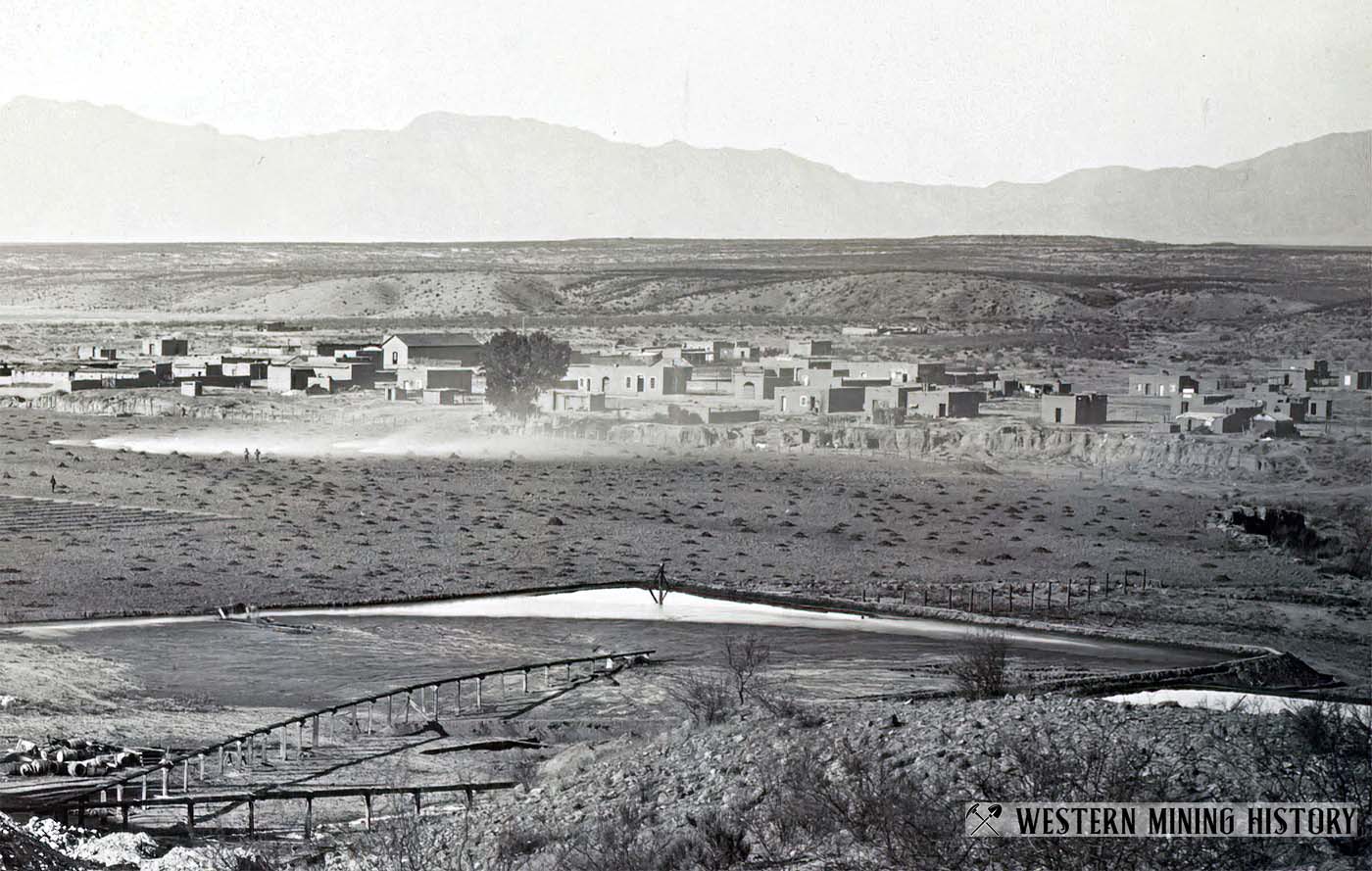

Charleston was laid out across the river from Millville to house the mill workers. Charleston's post office opened on April 17, 1879. Millville's post office opened shortly after Charleston's, on May 26, 1879, but shut down less than a year later on May 3, 1880 as it became clear that Charleston was to be the primary residence for the people of both towns.

Charleston grew quickly, and soon the town had four restaurants, a school, a church, a doctor, a lawyer, a drugstore, two blacksmiths, two livery stables, two butcher shops, two bakeries, a hotel, five general stores, a jewelry shop, a carpenter, a brickyard, a brewery, and at least four saloons. One of the butcher shops in town was owned by noted frontier lawman John H. Slaughter.

Charleston had a lawless reputation and was connected to many of the infamous characters associated with the Gunfight at the OK Corral in Tombstone which involved the Earp Brothers, Doc Holliday, and a band of famous outlaws.

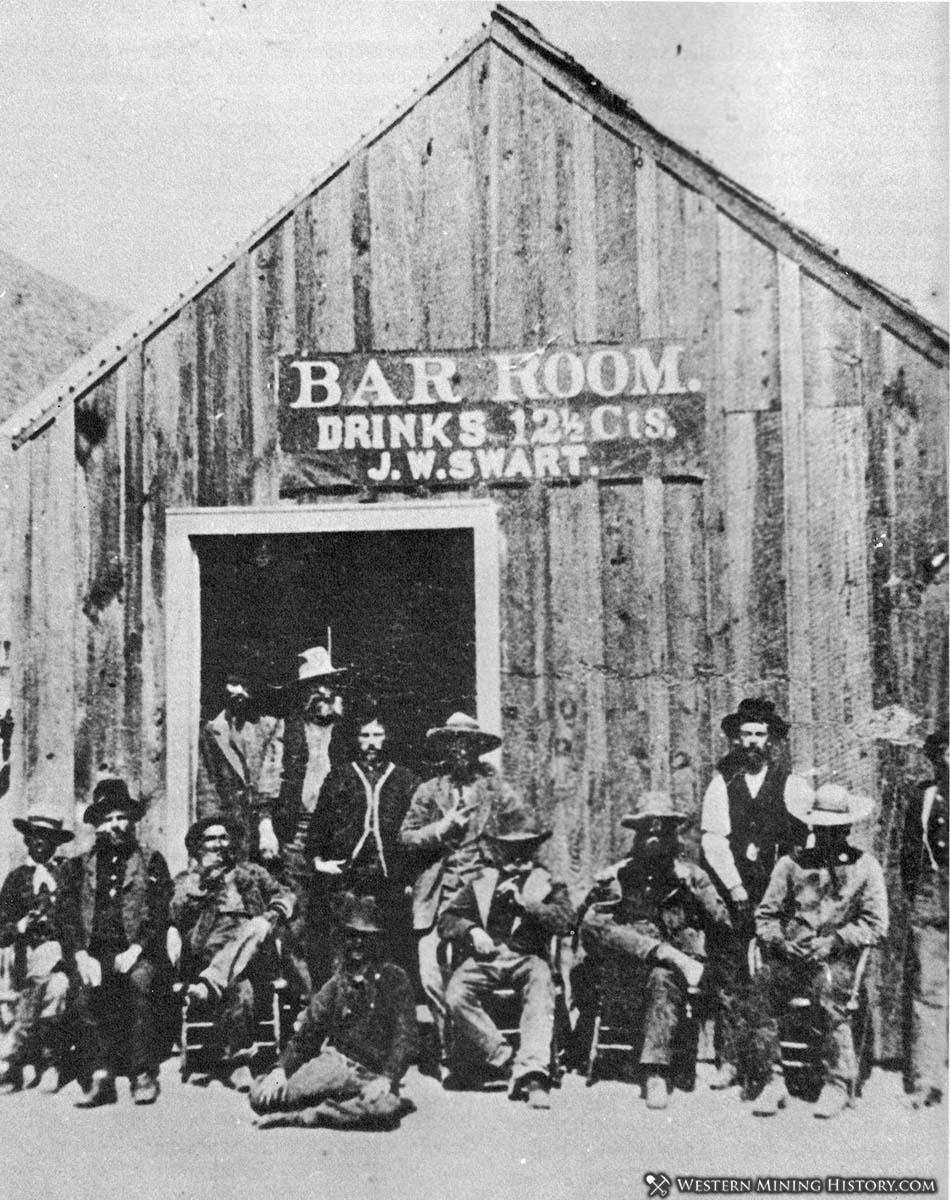

Noted outlaw Frank Stilwell owned a saloon in Charleston, before selling it to Jacob W. Swart in 1881. The Clanton Ranch, owned by "Old Man" Clanton, and run by his sons John, Phin, Ike and Billy, was located just five miles south of town. Some of the most infamous figures in the territory at the time were employed by or associated with the Clanton Ranch, including the Clantons themselves, Johnny Ringo, "Curly Bill" Brocius, Pete Spence, and Frank and Tom McLaury.

Despite its reputation and its infamous residents, the town never suffered a single successful robbery of either silver or money at the hands of outlaws, though a failed robbery of the Tombstone Mining Company which resulted in the murder of mining engineer M. R. Peel was reported in Millville on March 25, 1882.

The Tombstone Epitaph on May 6, 1882 said of Charleston that it was "well regulated and free from turmoil" and that it was "one of the most peaceful places we were ever in." Either that statement was an attempt by the newspaper to promote the town, or Charleston's reputation as a nest of outlaws was fading after the events that followed the gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

When the silver mines in Tombstone flooded in 1886, the mills were forced to shut down, and Charleston and Millville went into steep decline.

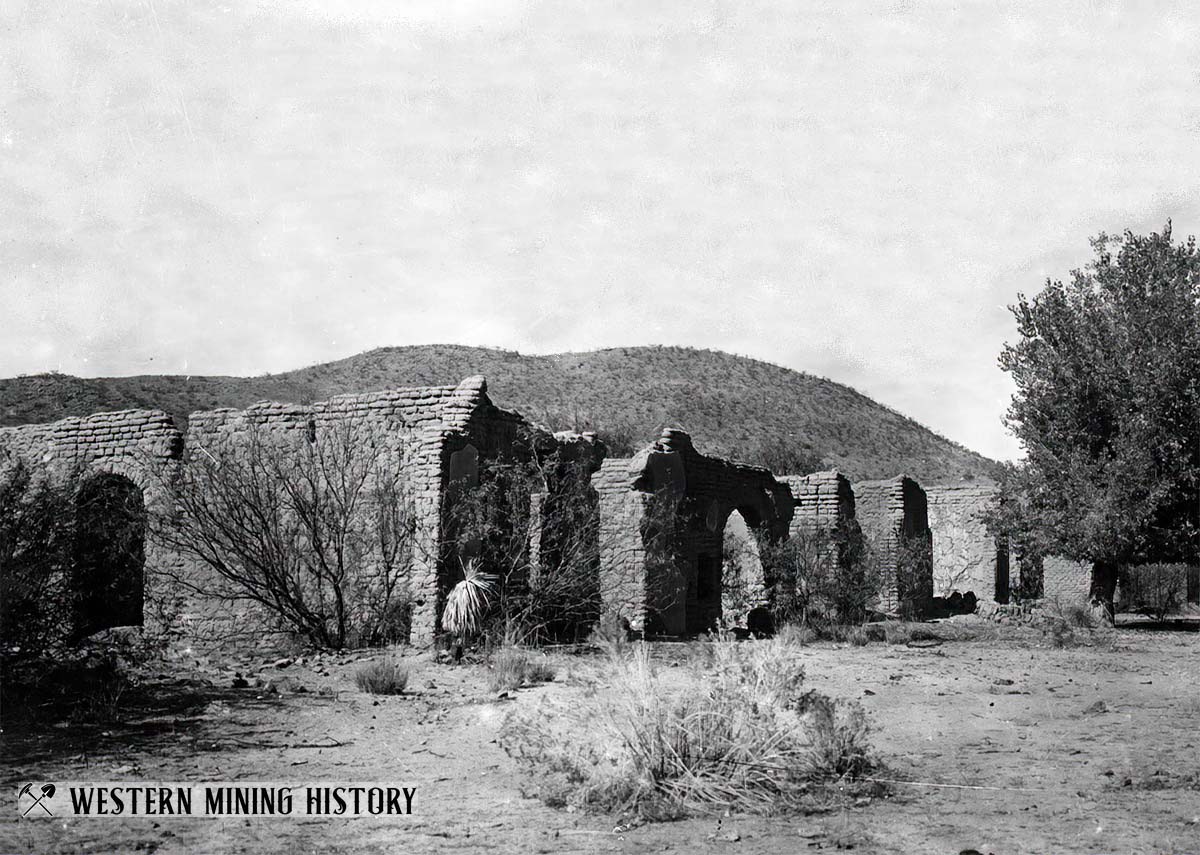

The large Sonoran earthquake that struck on May 3, 1887, accompanied by more than thirty minutes of aftershocks, left all of the town's adobe structures in ruins, sealing the town's fate. The town was quickly abandoned as none of the structures remained habitable.

The Charleston Post Office shut down on October 24, 1888, and by 1889, both Charleston and Millville were already ghost towns.

Charleston Described in 1878

From the Mar 27, 1892 edition of the Tombstone Weekly Epitaph.

Tombstone was booming in 1878. The Contention, Grand Central, Toughnut, Lucky Cuss, Vizina and Head Center, together with other bonanza claims, were turning out the richest of carbonate and chloride ores, and Tombstone District, which but a short year or so before was the undisputed haunt of the Apache, was now teeming with life and animation.

Contention Hill was now dotted with great hoisting works, and towards Tombstone, the restless searchers after live mining camps turned their foot-steps. The ore from these rich mines was milled at Charleston, a milling camp on the San Pedro river in south-eastern Arizona.

Charleston was nine miles distant from Tombstone, and the road between the two places was a busy thoroughfare, lined as it was with huge ore wagons drawn by from sixteen to twenty animals who tugged at the traces in response to black-snake whips, and the desert air fairly shuddered, as the dust begrimed teamsters yelled at the patient mules in "beautiful language soft and sweet."

Architecturally considered, Charleston was not a success, variety was lacking in the rambling adobe structures, more useful than ornamental. Along the banks of the river were scattered the camps of the prospectors and the "schaks" of the Sonoranians, and when the shades of night had fallen, the voice of the Arizona canary (jackass) was abroad in tho land, mingling in soft cadence with the dolorous chant of the musical Mexicanos.

The population of Charleston was mainly composed of men employed in and around the reduction works; in addition to these, however, the stock-men along the river made it their headquarters; the troopers from Fort Huachuca dropped in as often as Uncle Sam's regulations would permit and carefuly sampled Charleston whisky.

Prospectors purchased their outfits; Mexican traders favored the merchants with their patronage, and numerous trains of burros laden with goods, upon which the Mexican Customs officials failed to collect the extortionate duties imposed, crossed the Sonora line; and last but not least, a choice selection of desperadoes, who, from a constitutional dislike to be interviewed by the officers of the law, found Charleston, on account of its close proximity to the boundary line, a desirable place of residence, and under cover of night, many a head of stock passed down the valley, such stock having come into possession of the festive cowboy without the formal- ity of a bill of sale.

Charleston was indeed "painted red" when the last named element "whooped up" The crack of the revolver then became a familiar sound, and much valuable time was lost by leading citizens through serving on coroner's juries. Money was plenty: Miners were paid $4 and mill men and mechanics $5 to $7 per day. The lowest coin in circulation was two bits: nickles were unknown.

No railroad had crossed the territory, and there was no demand for cheap labor to harvest the crop of bullion that flowed from the mills, the roar and rumble of whose stamps echoed and re-echoed across the valley of the San Pedro. In fact, Charleston was a "live camp."

Arizona Mining Photos

View over 35 historic Arizona mining scenes at A Collection of Arizona Mining Photos.

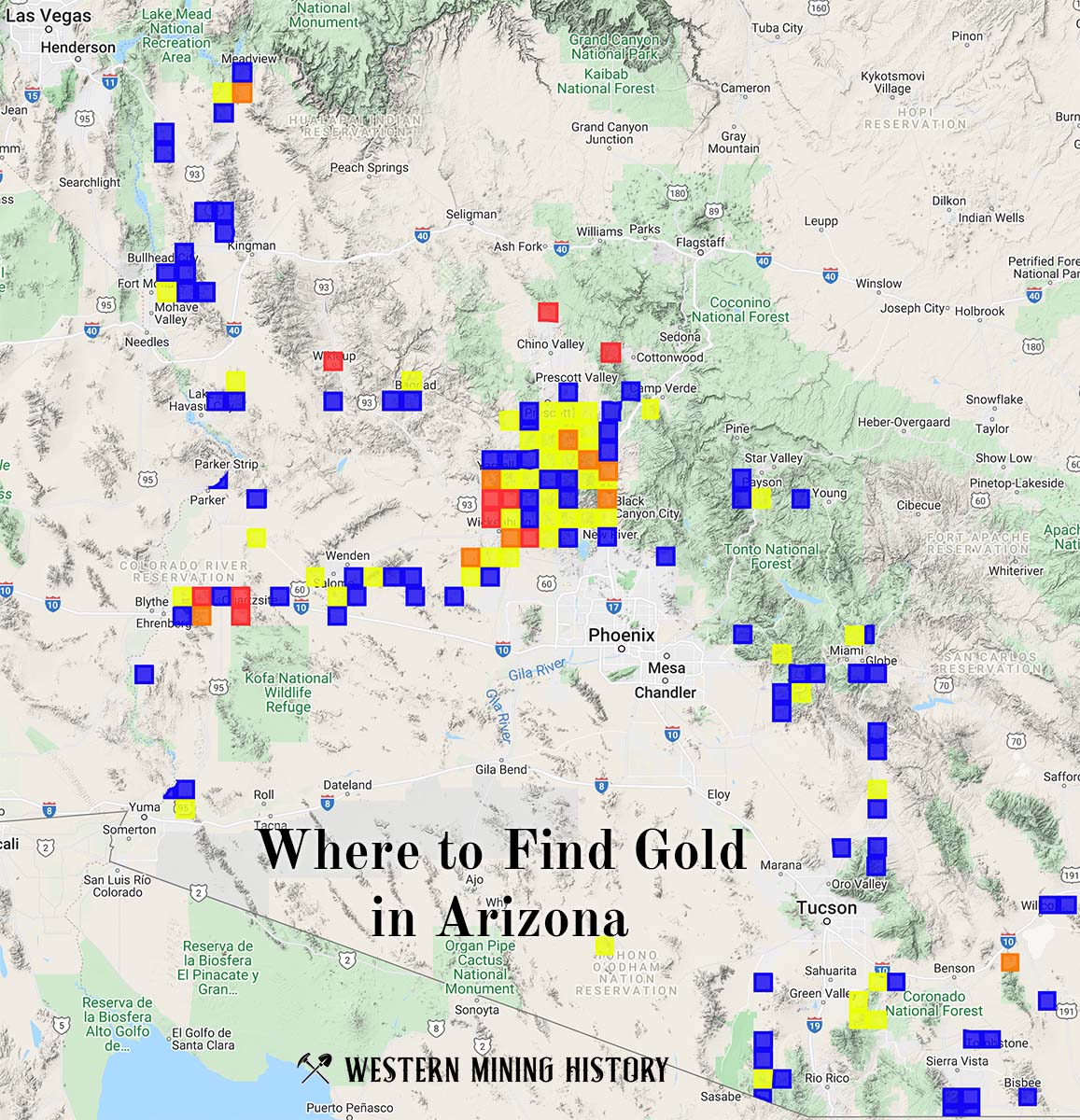

Arizona Gold

"Where to Find Gold in Arizona" looks at the density of modern placer mining claims along with historical gold mining locations and mining district descriptions to determine areas of high gold discovery potential in Arizona. Read more: Where to Find Gold in Arizona.