New Almaden History

New Almaden is California's first mining settlement, predating the earliest of the famous gold-rush towns. Mercury ore was identified at the site in 1845 and mining operations commenced a short time later.

Mercury (also known as quicksliver) was crucial to the recovery of gold, and when the California Gold Rush started in 1849, New Almaden was uniquely positioned to supply mercury to the new mines. The New Almaden deposit was rich, and the mine became California's largest producer of mercury for over 50 years.

Early History

Although mercury ore was 'discovered' in 1845, leading to the establishment of New Almaden, native inhabitants of California and southern Oregon had been aware of these mineral deposits for decades prior. Natives used the minerals from the "Red Cave" to paint their bodies a vermillion color. Historical accounts suggest that this cave was at least partially excavated by the natives, as Mexican visitors to the site described finding crude excavation tools and the skeletons of men that had been killed in a cave in.

Mexican prospectors had been aware of the deposit long before its 1845 discovery. During the 1820s and 1830s, they visited the site and recognized the metallic quality of the ore, mistakenly believing it contained silver. Ironically these early prospectors used quicksilver in an attempt to recover the silver content of the ore. When these early attempts failed, the deposit was abandoned and it would be many years before the the nature of the mineral deposit at Red Cave was realized.

It was Don Andreas Castillero, a Mexican army officer, that finally solved the puzzle of the heavy red ore. Castillero was shown a sample of the ore which intrigued him, so he visited the mine and collected his own samples. He then returned to the fort at the Santa Clara Mission where he pulverized and roasted the ore in a crude furnace that he made with hot coals and a tumbler. The result of his experiment was his tumbler frosted with minute globules of metal, which he recognized as quicksilver.

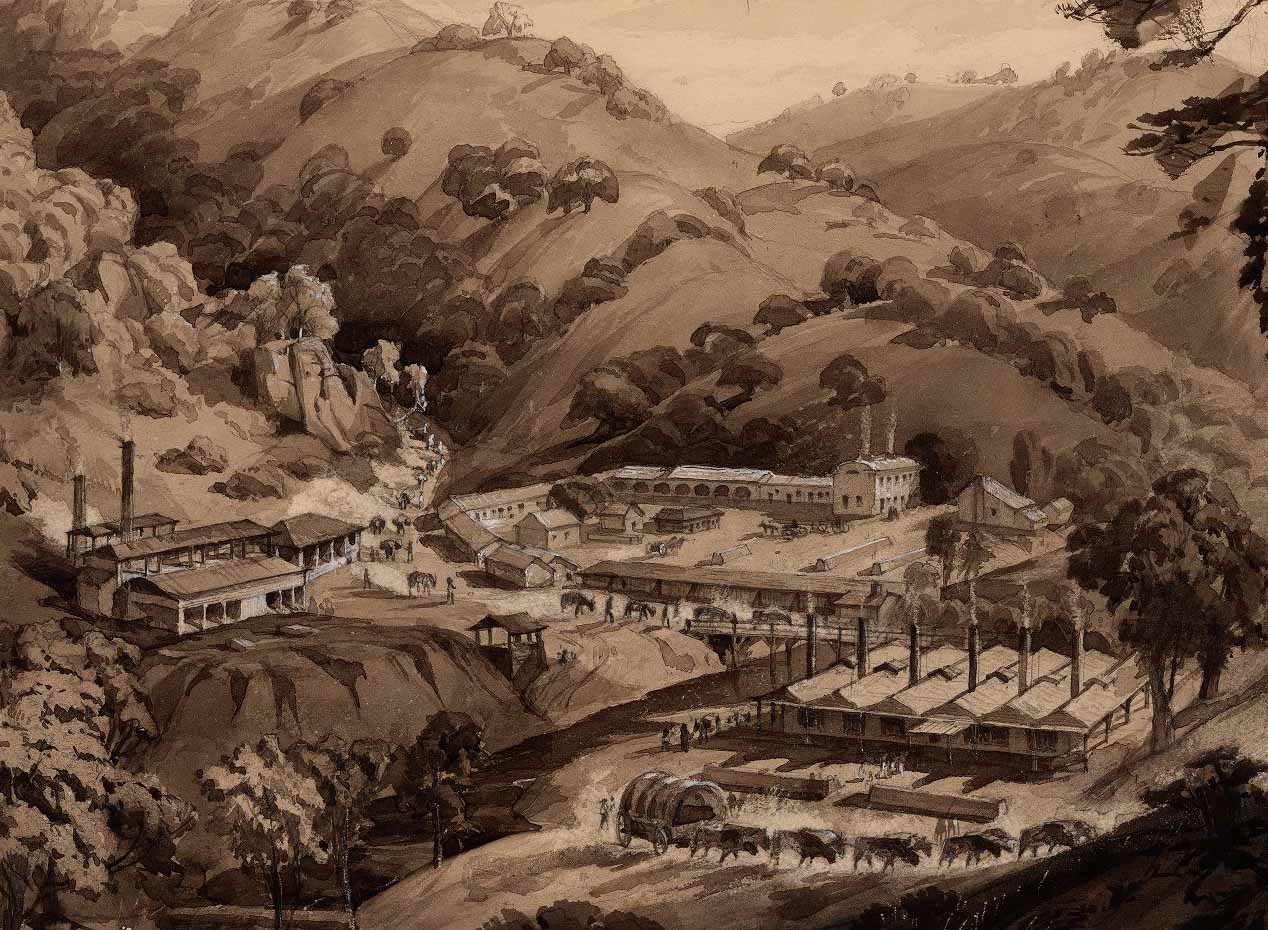

Castillero made a claim to the mine, which he called the Santa Clara, with the Mexican government. A company was formed and mining commenced in early 1846. Even with the crudest methods of mining and refining being used in this early operation, over 2,000 pounds of quicksilver was recovered. This early activity confirmed that this was fabulously rich "bonanza" ore, and the Barron, Forbes, & Co. was brought in to supply the capital needed to properly develop the mine. The mine was renamed "New Almaden" after the Almaden mine in Spain which was the world's greatest at the time.

By 1848, improvements in ore roasting techniques were yielding significant improvements in quicksilver recovery. In one three-week period 10,000 pounds of quicksilver was recovered, and in a separate two-month period 20,000 pounds was recovered. At this time only six miners were working on the property, which highlights just how rich the ore was during this early period of the mine's history.

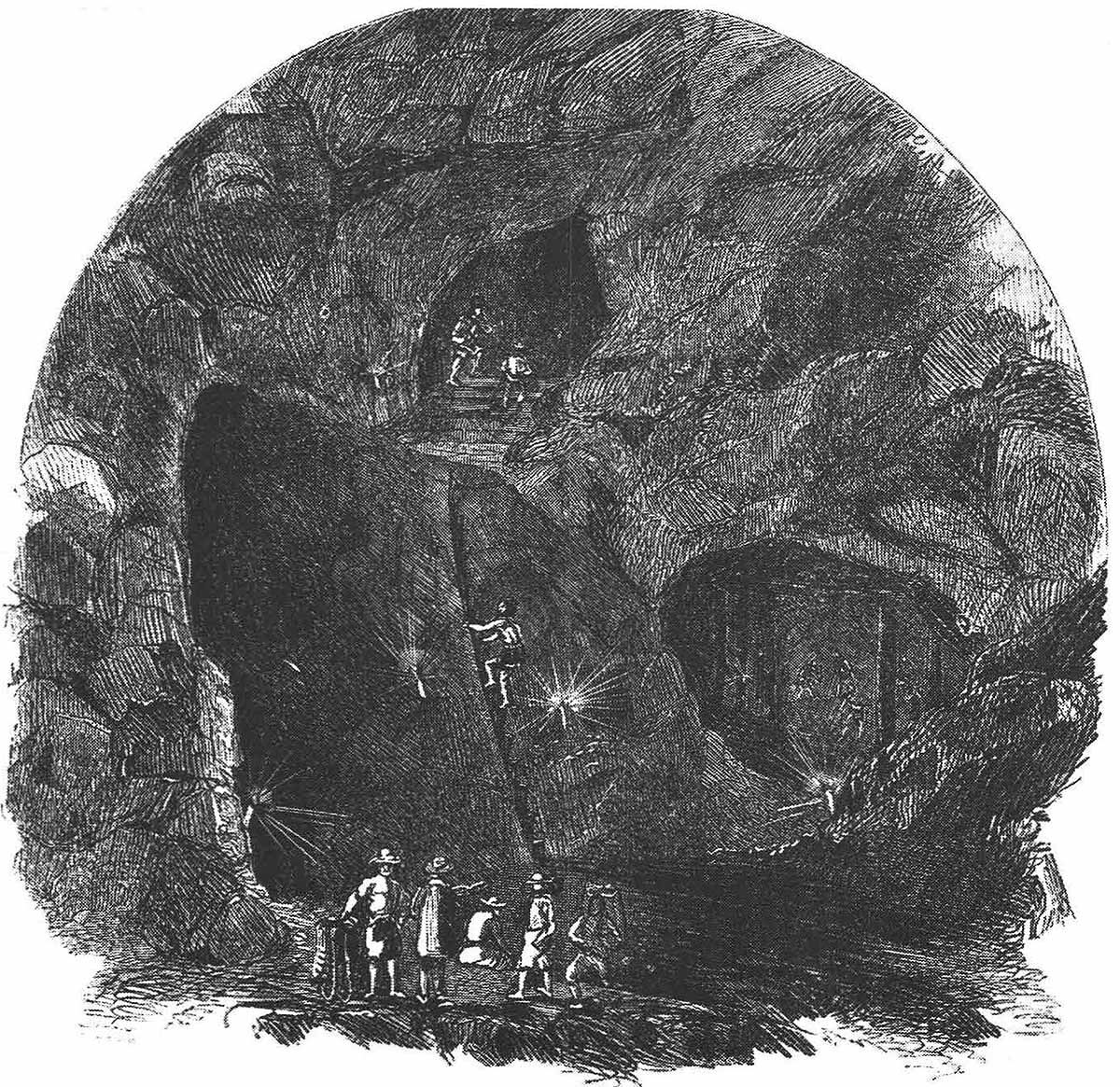

By the 1850s, much of the underground labor was done by Yaqui Indians. Using large leather backpacks, they carried 200 pounds of ore up notched log ladders, with the expected day's work consisting of 25 to 30 such trips up more than 200 feet of ladder.

Over the next few years the mine expanded rapidly and was producing over $1,000,000 worth of quicksilver every year (over $40,000,000 today). Trouble was on the horizon however as the great California Gold Rush and the subsequent admission of California to the Union in 1850 drastically changed the region's political landscape. The U.S. Congress established the Board of Land Commissioners in California and required that all land grants previously awarded by the Mexican government be reviewed. New Almaden was one of the most valuable such grants in the state, and the legal battle that ensued over control of the property attained national prominence and ultimately lasted almost a decade.

The full account of the legal battle is a long and complicated story, but it culminated in 1863 with Abraham Lincoln sending a U.S. Marshal to the New Almaden property to evict the Barron, Forbes, & Co. that had operated the mine since the late 1840s. A standoff ensued when 170 armed miners refused the Marshall's group entry to the property. Lincoln planned to send Federal calvary to take the mine by force, but public sentiment in California was turning against the government over fears they would seize more California mines. Concerned that California might align with the Confederacy during the Civil War, Lincoln changed his stance and rescinded the order to seize the property.

By the summer of 1863 a deal had been struck that saw the Quicksilver Mining Co. pay $1,750,000 to Barron, Forbes, & Co. for clear title to the New Almaden property. On September 1, 1863, the new company began a 50-year period of operation of the mine.

Quicksilver Mining Company Era

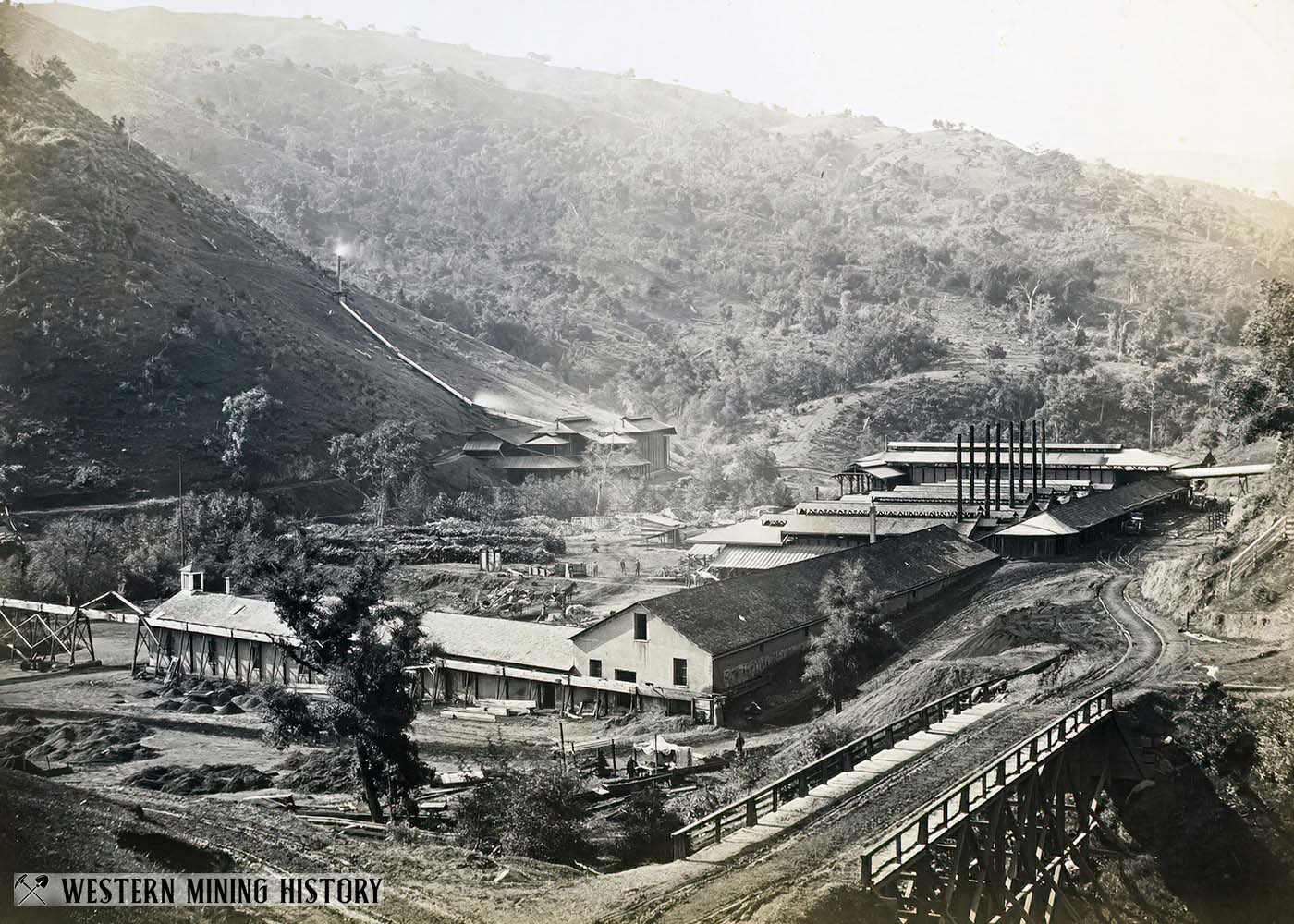

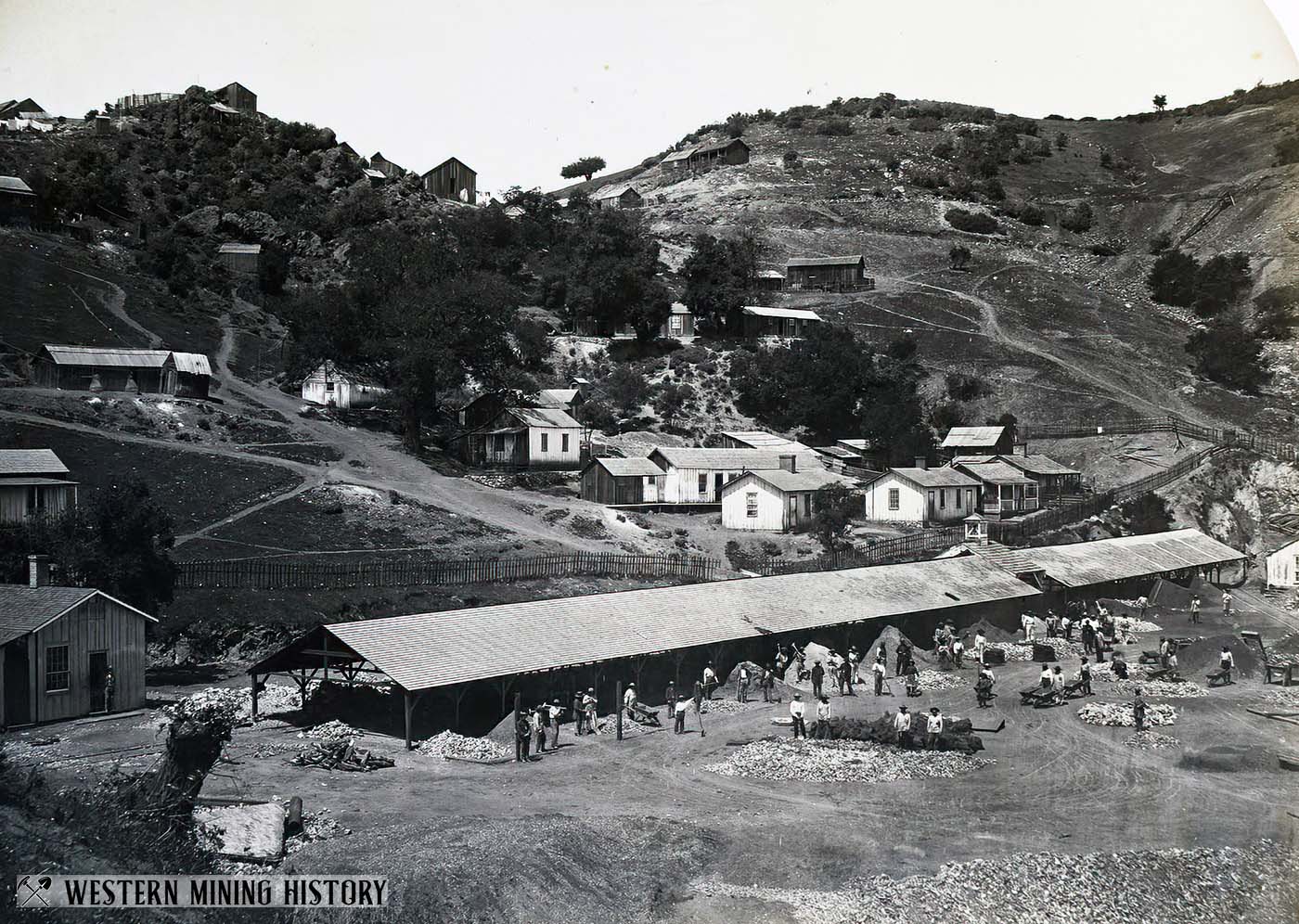

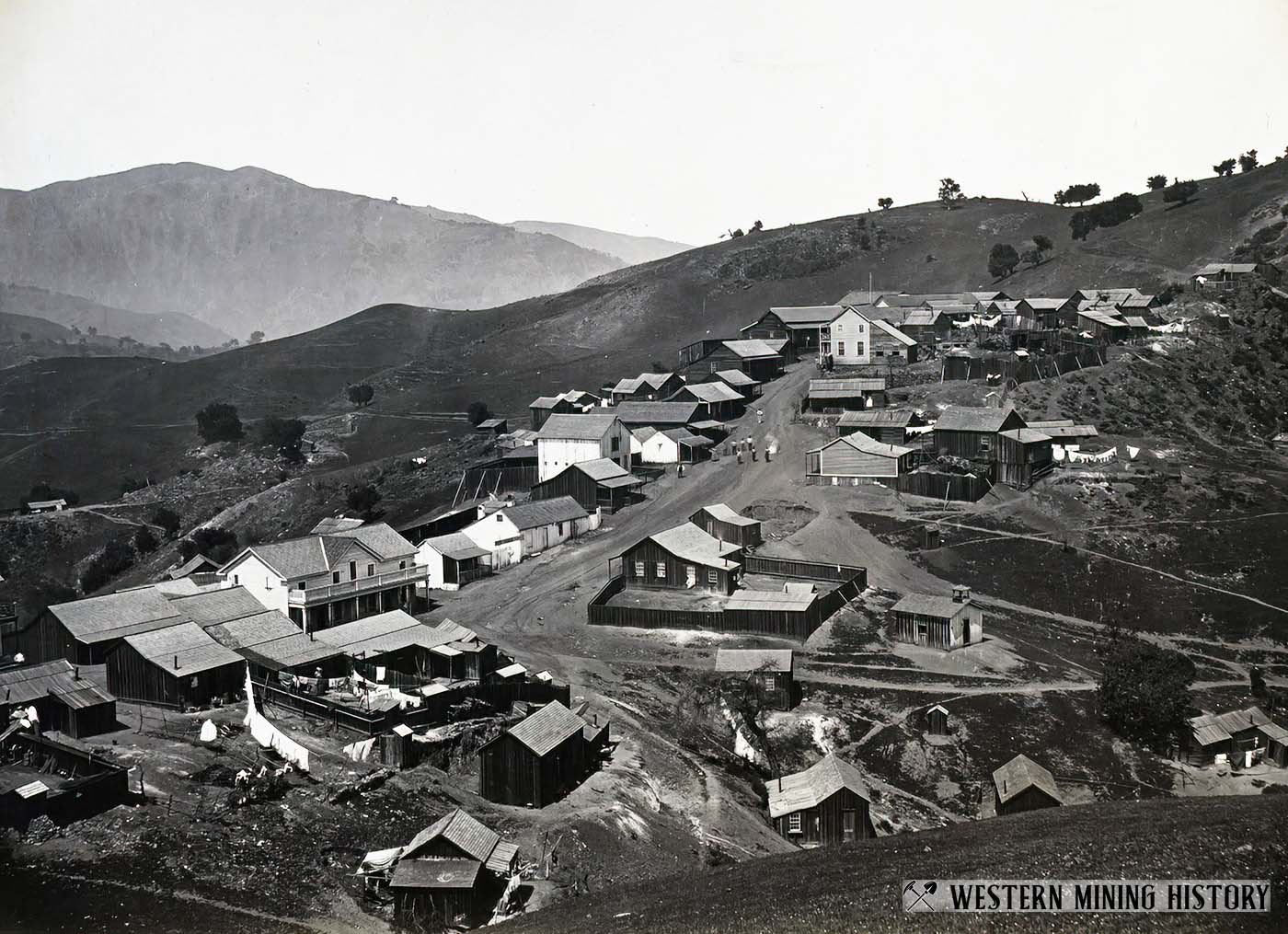

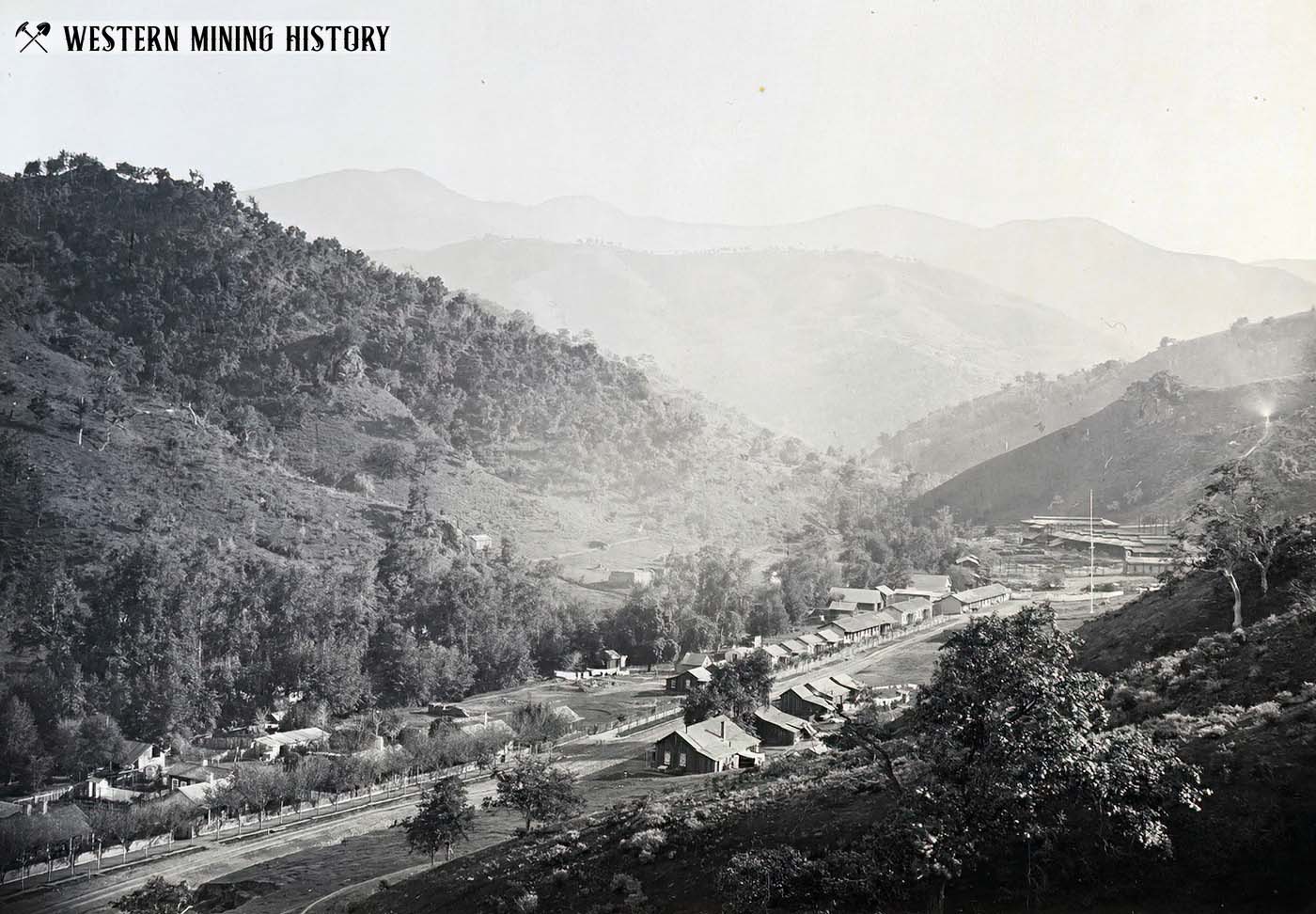

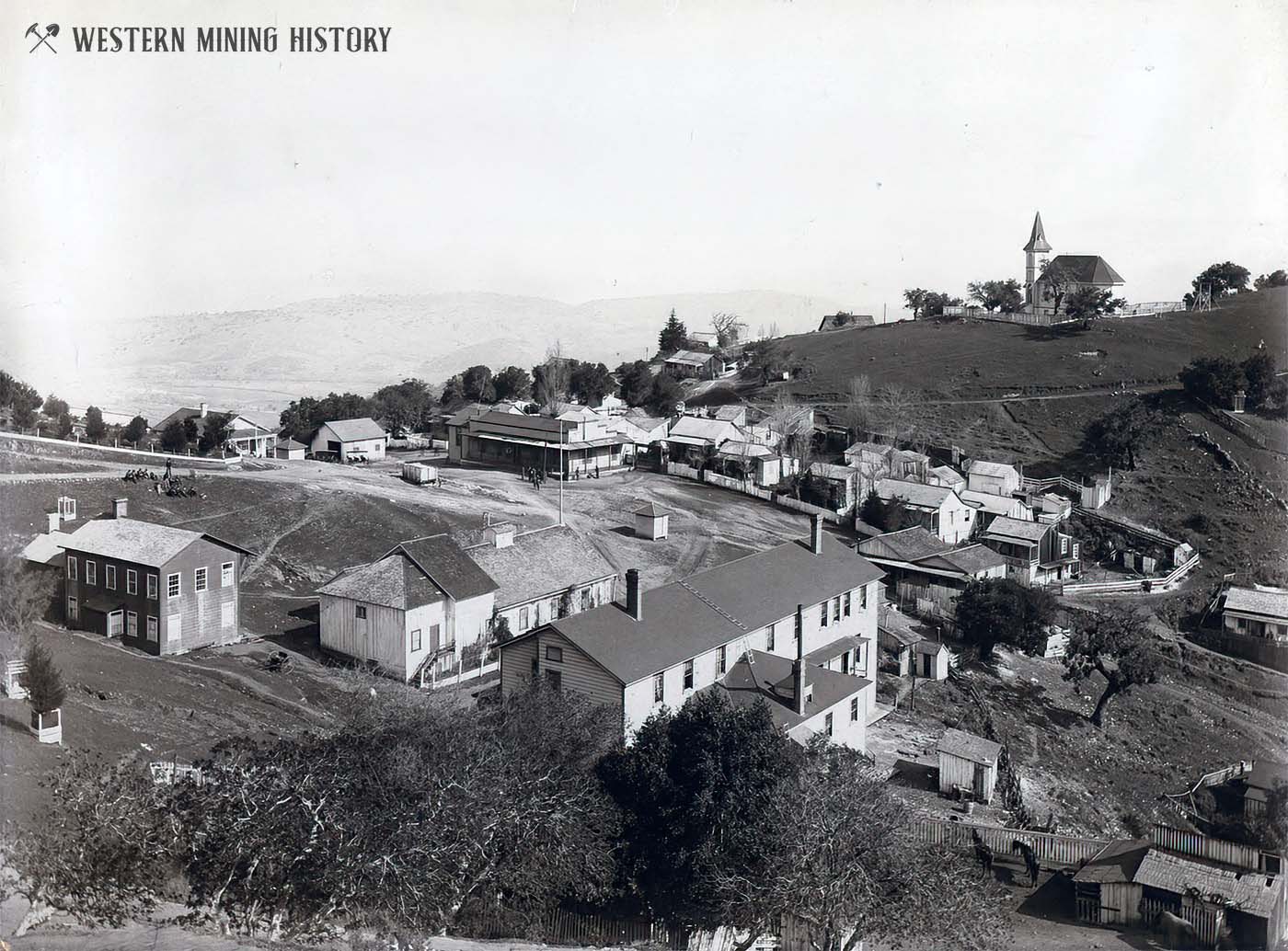

By the time the Quicksilver Mining Co. took over operations in late 1863 the communities of New Almaden were already well established. There were three settlements: management and furnace workers resided at the 'Hacienda,' while miners lived in Englishtown and Spanishtown. At its peak, New Almaden had over 3,000 residents, many of whom came from England, South America, and China. The "Casa Grande" mansion, built in 1854, was originally a hotel but later served the mine manager's residence.

In the eight months prior to New Almaden changing ownership, the Barron, Forbes, & Co. had stopped development work at the mine and focused entirely on mining out all the best ore from the stopes. The Quicksilver Mining Co. was forced to focus its early operations on processing the low grade ore available to them while exploring for new ore bodies. The exploration paid off and two significant new ore bodies were found first in August of 1864, then again in early 1865.

By 1865 over 2,000 men were employed at the mine, at an average daily wage of $2.50. High wages led to lavish spending, making the camp famous for its payday celebrations and reputation for lawlessness.

Between 1864 and 1870, New Almaden supplied the entire demand for quicksilver in the United States, and also exported to China, Mexico, and South America. However, by 1870 both the quantity and quality of the mercury ore being mined was falling dramatically. In a bid to turn the mine around, J.B. Randol was hired as General Manager in 1870. Randol implemented significant changes to both the communities and the mines of New Almaden, ushering in a new era of prosperity.

Randol set about to change the communities of New Almaden from notoriously lawless and dirty camps to clean, orderly settlements. He posted edicts in both English and Spanish on many bulletin boards throughout the property, and then saw to it that the edicts were carried out. The first edict mandated that every able-bodied man living on the property must be employed by the mining company, aiming to rid the area of undesirable residents such as gamblers and drunks. Everyone was required to contribute a dollar a month to the “Miners’ Fund,” which offered miners and their families free access to a first-class physician and surgeon, dental care, as well as literary programs and educational lectures.

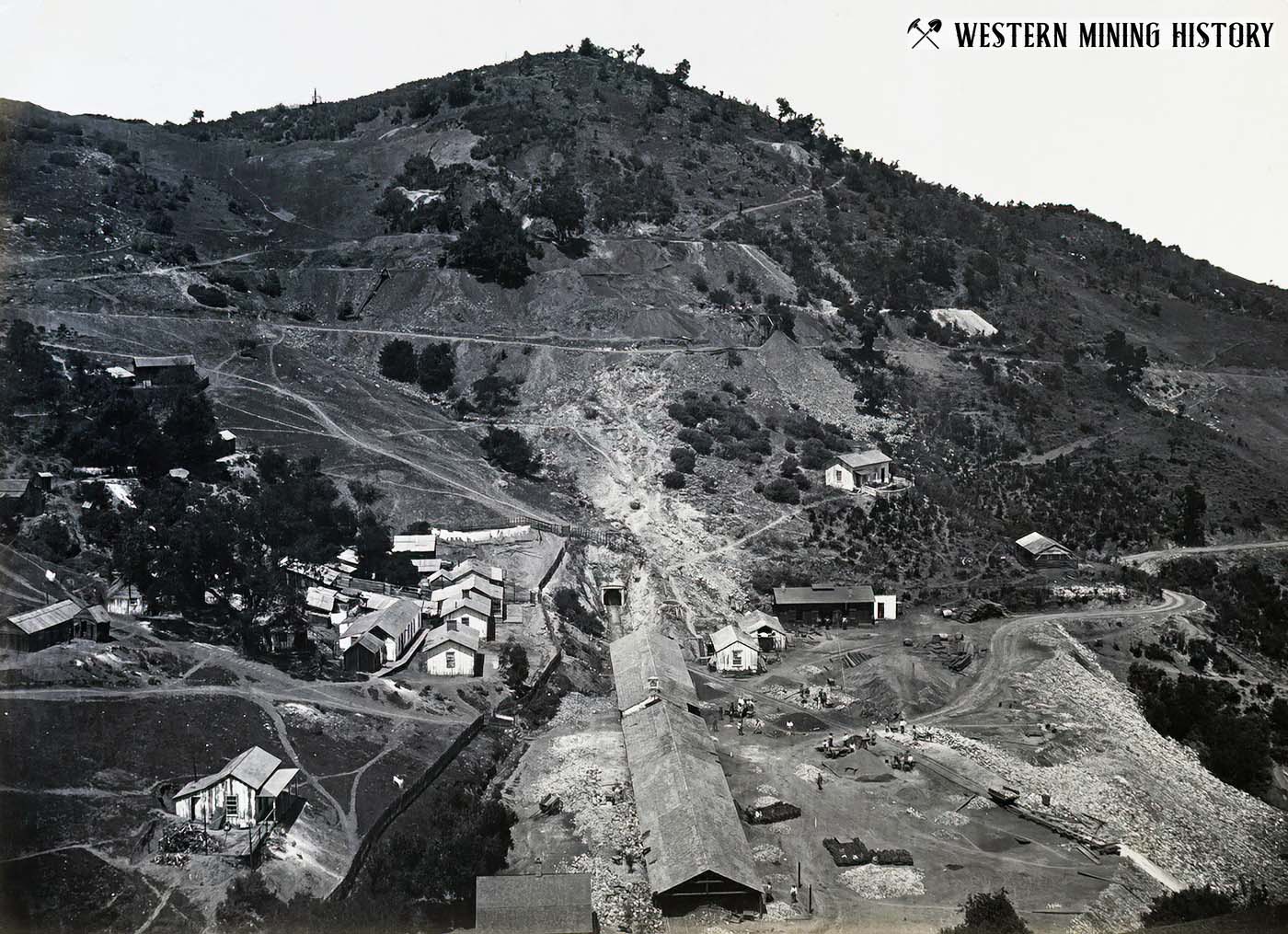

To address the declining ore reserves, Randol initiated an ambitious exploration and development program. Over the next two decades, many new shafts and tunnels were excavated at significant cost. While not every effort was successful, Randol's strategy proved largely effective, leading to the discovery of numerous new ore bodies.

After nearly two decades as General Manager, Randol left New Almaden in 1889. By this time, the quantity and grade of the ore were once again in serious decline. The new management once again turned to exploration in hopes of discovering new deposits. One shaft was driven to a depth of 2,450 feet, the deepest shaft of any quicksilver mine in the world.

Ultimately a combination of new ore discoveries, the mining of an open cut on the surface at Mine Hill, and reprocessing old dumps and stope fills prolonged the life beyond the year 1900. Few new discoveries were being made after 1900 however, resulting in miners and their families leaving the settlements in large numbers. By 1909 the property was largely a ghost town. The Quicksilver Mining Company, owner of the New Almaden mine, went bankrupt in 1912.

New Almaden in the New Century

In subsequent years, the mine and surrounding communities experienced a long and colorful history that alternately included mining and recreational resort development. Starting in 1926, wealthy residents of San Francisco used the area as a retreat, turning Hacienda homes into vacation cabins and building new homes on vacant lots. Civilian Conservation Corp workers lived in Englishtown during the 1930's.

The second World War spurred interest in mercury mining, resulting in new furnaces being built and the commencement open-pit mining. After the war, only small scale mining occurred until the operation was finally shut down in 1970.

According to the USGS, by the end of 1945 the total production of all the New Almaden mines reached 1,046,198 flasks of quicksilver, with 93 percent of that amount recovered before 1900.

Today, New Almaden is the location of a National Historic Landmark district and a county park. The New Almaden Quicksilver Mining Museum is located in the historic Casa Grande building.

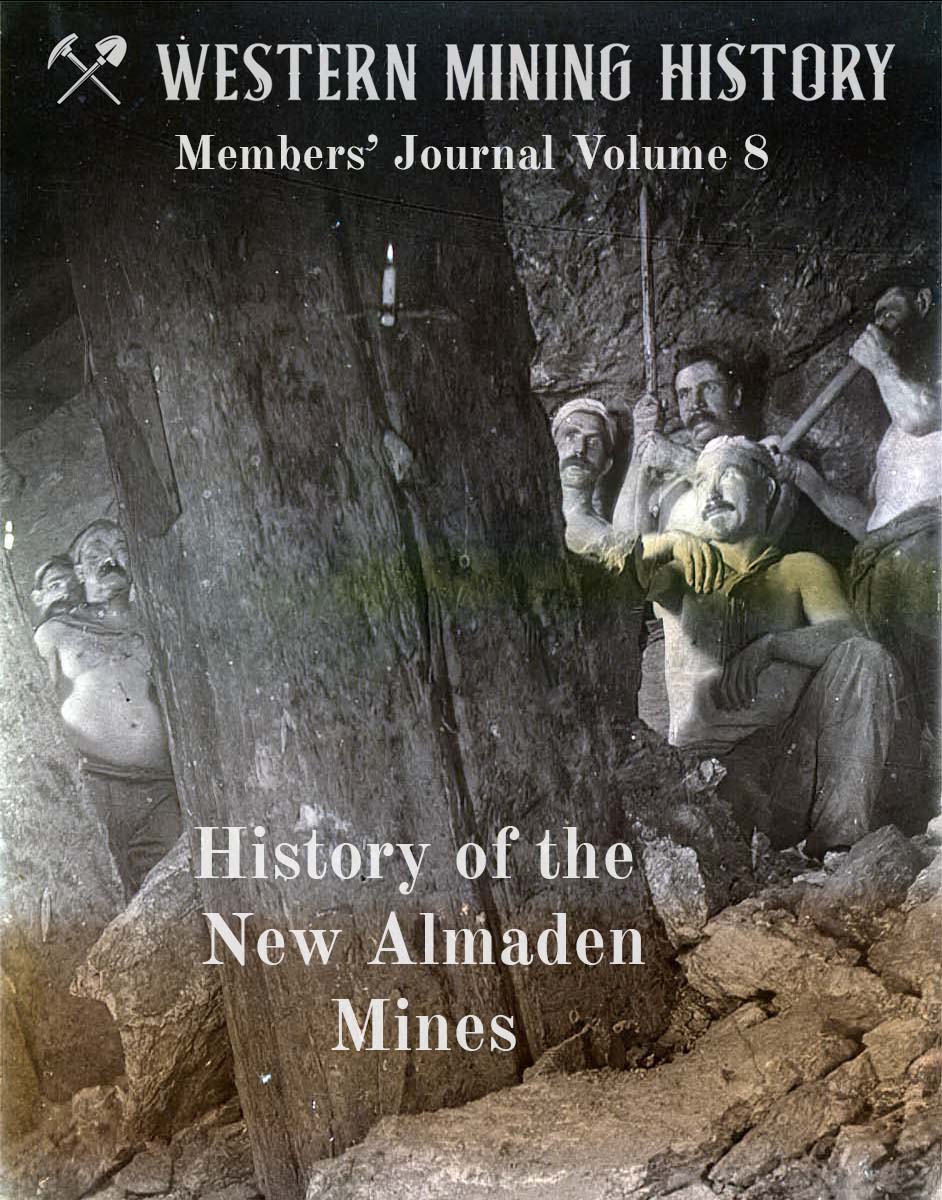

History of the New Almaden Mines

The WMH Member's Journal Volume 8 - History of the New Almaden Mines is a much more detailed history of the fascinating New Almaden quicksilver mines, including numerous additional historical images. "Mining started at New Almaden in 1846, and in the early years when the most valuable ore was being extracted the works here resembled Tolkien’s Mines of Moria more than the organized industrial operations that rapidly evolved in the goldfields of California, the Comstock Lode, and throughout the western states."

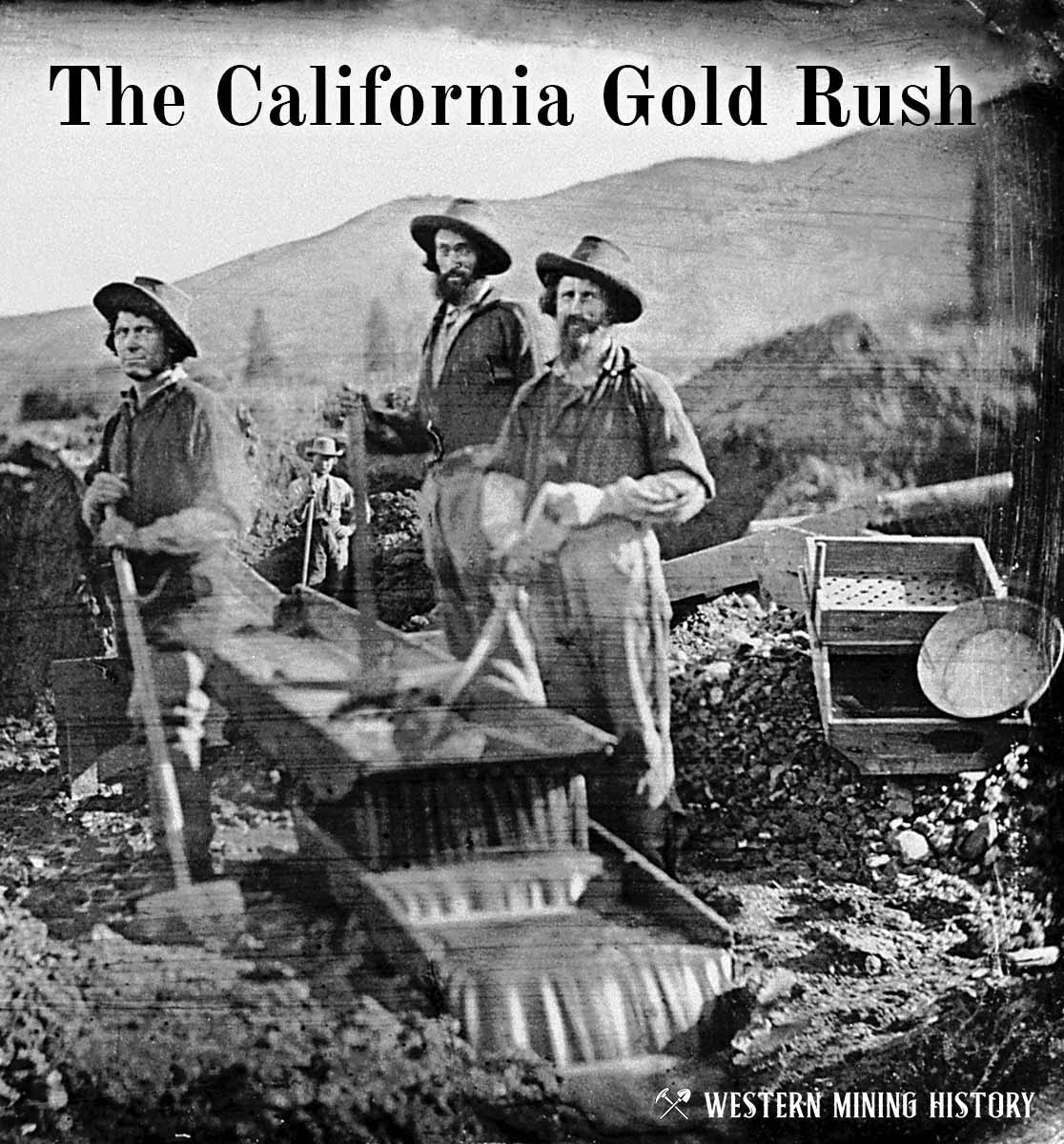

It All Started With The Gold Rush

The great California Gold Rush kicked off the entire saga of western mining. Read about it at The California Gold Rush.

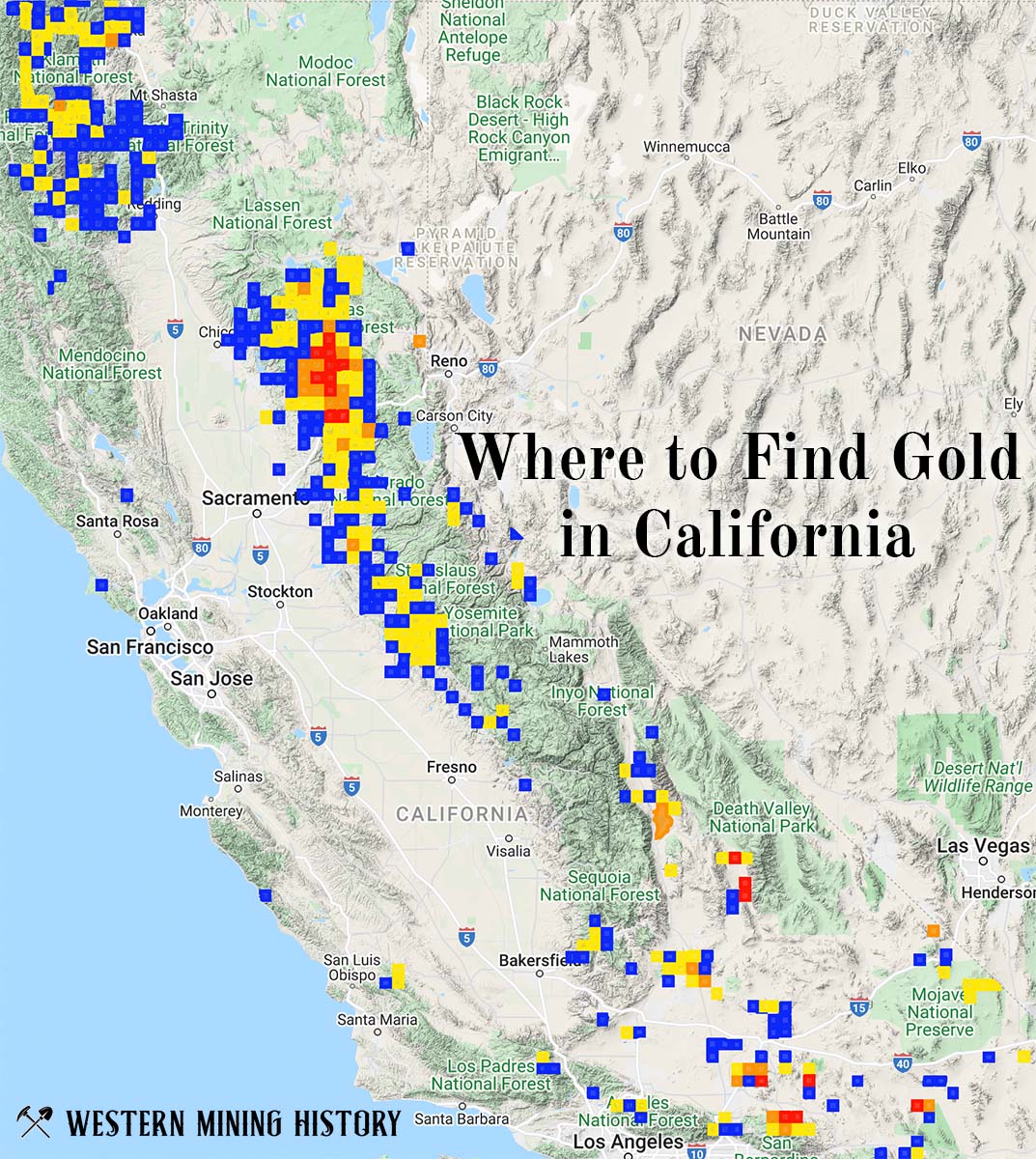

California Gold

"Where to Find Gold in California" looks at the density of modern placer mining claims along with historical gold mining locations and mining district descriptions to determine areas of high gold discovery potential in California. Read more: Where to Find Gold in California.