St. Elmo History

Prospectors Abner Wright and John Royal discovered a valuable silver deposit in Chalk Creek Canyon in 1875 at what would become the Mary Murphy mine, the district's largest and longest lasting producer.

St. Elmo, originally named Forest City, was settled near the Mary Murphy Mine in the late 1870’s. The town thrived during the 1880’s as the local mines employed hundreds of men and were producing millions of dollars a year in gold and silver.

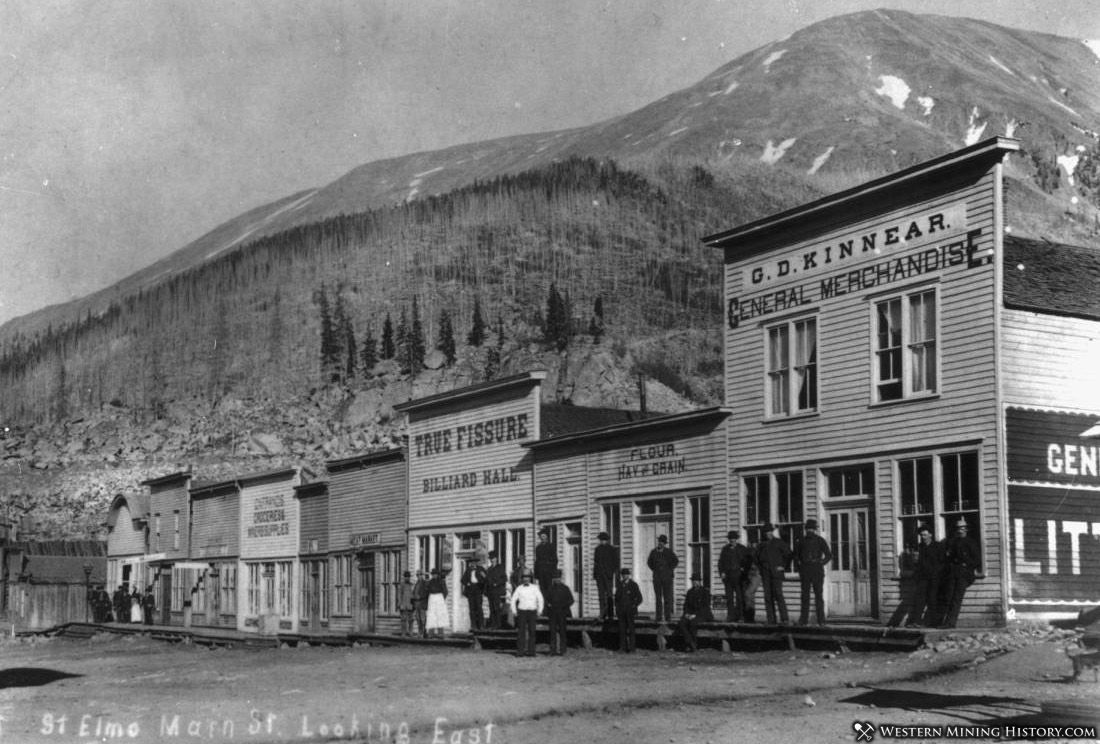

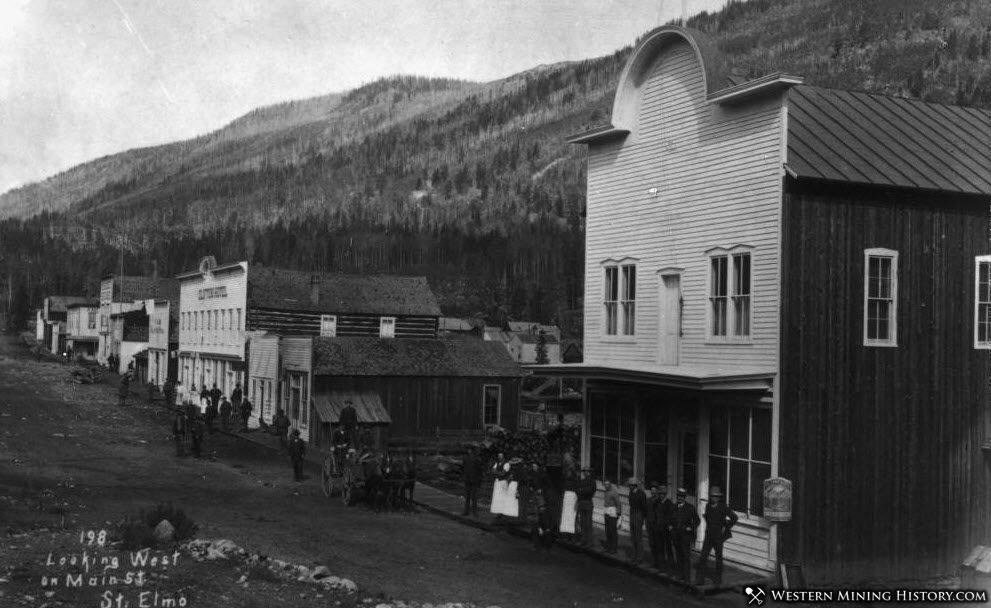

The town peaked early in its history with an estimated 2,000 residents. In 1881 St. Elmo had two sawmills, a smelter and concentrator, 3 hotels, 5 restaurants, a newspaper, and numerous other businesses. New ore deposits were being discovered on a regular basis, and by 1883 the district had over 50 working mines.

In 1880 the Denver, South Park and Pacific Railroad completed a line to St Elmo. A massive project was then started to drive the Alpine Tunnel west through the continental divide. This 1,772 foot tunnel was at the time the highest altitude and most expensive railroad tunnel ever built. The tunnel took 18 months to complete.

With St. Elmo now on a spur of a major rail line, good times seemed ensured for the camp for many years to come. In 1885, the Colorado Daily Chieftain reported “The South Park railroad will make St. Elmo the point of transfer for its Aspen freight, and the St. Elmo people are naturally pleased over the prospect.”

St. Elmo declines

Despite all the momentum of the first half of the 1880s, St. Elmo began to decline in the latter half of that decade. Much of the ore in the St. Elmo mines was low grade which resulted in poor revenue at many of the mines and less interest in exploration for new deposits.

Many residents had already left St. Elmo when a fire burnt part of the town in 1890, resulting in even more residents packing up for good. By 1891 the town had a population of just 500. The silver crash of 1893 dealt another blow to the local economy and the population further declined.

Another fire in 1898 burned much of St. Elmo’s commercial district. Just a year later, yet another fire struck the town, burning many of the buildings that had just been built after the 1898 fire. By this time a decade of economic hardship and multiple fires had permanently diminished this once great mining camp.

St. Elmo was not done however, and the first decade of the 1900s saw an improved outlook for the local mining industry. The Mary Murphy Mine was reopened and was among several mines that began new operations during this time.

The 1900s bring new prosperity

The Alpine Tunnel closed in 1910 and some sources report that this was the beginning of the end for the town of St. Elmo. However, newspapers from the time describe optimism as new discoveries starting in 1911 started to revive the local mining industry (Salida Record September 15, 1911):

BIG STRIKE AT THE MARY MURPHY MINE

From St. Elmo comes the report that a large ore-body has been penetrated by the Mary Murphy tunnel which is being driven into the mountain beneath the workings of the mine. It is said the vein matter exceeds a width of twenty-five feet and that the ore compares favorably with the best grades taken from the upper workings. By means of the tunnel a tremendous depth from the surface has been acquired and this strike proves the existence of unlimited bodies of pay ore. The outlook for St. Elmo and vicinity is brighter than at any time in the camp’s history.

The Salida Record reports on July 5, 1912 that “A good strike of free milling gold ore has just been made in the Black Hawk mine, 2 miles from St. Elmo, Chaffee county.”

By the summer of 1913, the district was buzzing with new activity. The Salida Mail reported:

ST. ELMO CAMP WORKING AGAIN

Camp With a Production of Twenty Millions of Dollars Enters an Era of Permanent Prosperity

St. Elmo has taken on a new growth eclipsing former days, entering a period of mining prosperity that places town and district permanently before the country as a gold-producing section of inexhaustible resources. Besides the great dividend paying Mary Murphy mine, employing hundreds of miners, other properties in the district have reached the goal of steady production, many are rapidly attaining that basis, and a large area of unexplored mineral land holds out vast possibilities to the prospector and capitalist.

St. Elmo the frontier tourist destination

Like many Colorado mining camps, St. Elmo sits in a beautiful alpine valley surrounded by towering mountain peaks. What is unusual is that the town was an early tourist destination, with descriptions of tourist excursions all the way back to the 1880s. In 1886 the Aspen Daily Times reports on sleigh rides between Aspen and St Elmo:

BEAUTIFUL SLEIGHING ON THE ST ELMO ROUTE

Passengers are carried between Aspen and St. Elmo without transfer. Large buffalo robes for wraps. Six horses, careful drivers, safe rides. The sleighs leave Aspen every morning at 6 a.m., arrive in St. Elmo at 5 p.m.

A 1913 article in the Salida Mail describes the beauty of Chalk Creek Canyon and St. Elmo:

St. Elmo is also rich in the sublimest scenery in the Rockies, and the streams, parks, dales and lakes hidden away in the recesses of its majestic old mountains offer irrectible allurement to health and pleasure seekers who would partake of Nature’s balsam at the fountainhead of the continent.

Hortense Hot Springs resort, down the canyon from St. Elmo, is mentioned as a popular tourist spot in the first decades of the 1900s and still operates as a resort today.

Life in a frontier mining camp

Not much has been recorded the daily life of the early citizens of St. Elmo but we can learn about some of the more noteworthy events from frontier newspaper articles.

Like many frontier mining camps, St. Elmo had its share of crime and violence. The Salida Record relates the details of a robbery that occured on August 21, 1914:

Last Saturday night two masked men entered Pat Hurley’s place at St. Elmo, secured $50 and a gun from the proprietor and relieved of their valuables several persons who were in the room. With their guns pointed at those within, the bandits backed out of the door and escaped to the mountains. The holdup occured at ten o’clock and, as usual, one of the bandits was tall of stature and the other short.

In 1912, food poisoning hit the Mary Murphy Mine boarding house as detailed by the Montrose Daily Press:

Oct. 24. Two men are dead and the third is dying from the effects of being poisoned by eating Wienerwursts and sauerkraut at the Mary Murphy, mine near St. Elmo. The dead are J. R. Gardner and Peter Johnson, two miners, while the superintendent of the mine Is now at his home in Buena Vista dying from the effects of the poison. His wife is prostrated with grief.

Although not many laws were in place to protect wildlife, it seems that dynamiting fish was one activity that was not tolerated in 1912 (reported by the Salida Record):

Reports have become current repeatedly of fish dynamiting near St. Elmo. Both this and last summer, evidences of blasts have been left in the lake beds at the head of Chalk Creek and the North Fork, many dead trout have been found on the surface of the waters which leaves no doubt in the minds of the people as to the cause.

The people of that vicinity are highly indignant over the matter and state that they will urge the highest penalty that can be imposed if the guilty parties can be brought to light.

The penalty for dynamiting fish is as follows, according to the statute: “Every person in violation of this act, shall be punished by a fine of not less than $500 nor more than $1,000, or by imprisonment in the penitentiary not less than six months or by both such line and imprisonment.”

St. Elmo becomes a ghost town

The boom of the 1910s waned by the end of the decade and the local mining industry was in serious decline. In 1922 railroad service to St. Elmo stopped, and in 1926 the rails were removed, which usually signaled the end of frontier mining camps.

The Mary Murphy mine continued to operate until 1936, extending the life of the St. Elmo into the Depression years.

By World War 2 the mining industry at St. Elmo was mostly idle and just two residents remained in the town. The remaining residents made a living by renting summer cabins to tourists. This small tourist operation provided just enough interest in the town to keep it preserved when it otherwise would have been abandoned and lost to time.

Today St. Elmo has a small year-round population with an active population of summer residents. The town has over 40 historical structures and is a popular destination for tourists with an estimated 50,000 visitors each summer season.

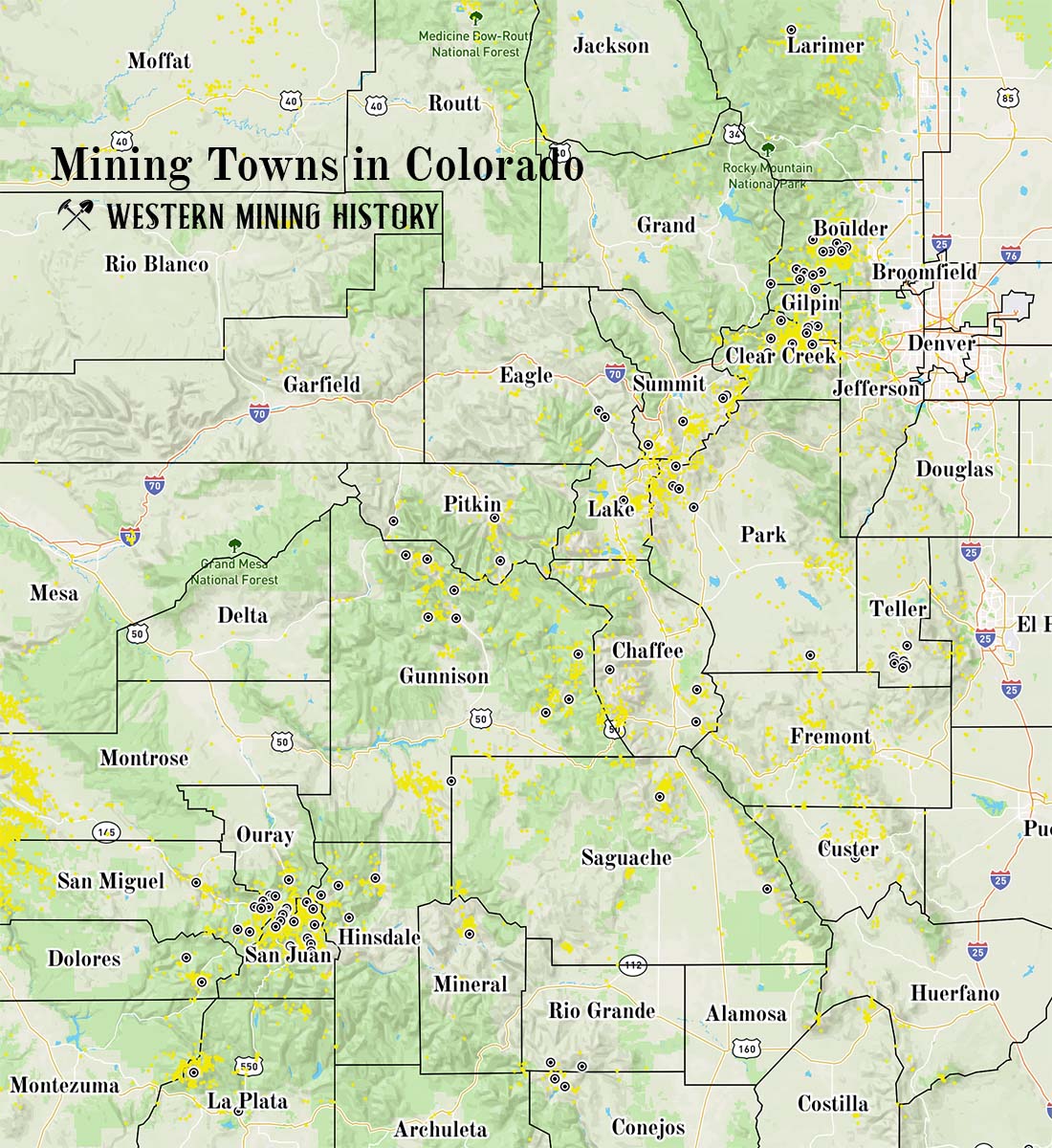

A Tour of Colorado Mining Towns

Explore over 100 Colorado mining towns: A tour of Colorado Mining Towns.

Colorado Mining Photos

More of Colorado's best historic mining photos: Incredible Photos of Colorado Mining Scenes.