Wallace History

Wallace, Idaho is the economic center of the Coeur d’ Alene Mining District, in a region known as the Silver Valley in northern Idaho. The Silver Valley is the richest silver mining district in the United States with over a billion ounces of silver mined, and is one of the top three most valuable silver districts in the entire world.

The first reported discovery of precious metals in the Coeur d’ Alene District was of gold in 1878, at a location west of the present day town of Wallace. The discovery was made by Andrew J. Prichard as he was traveling through the area on the Mullan Military Road, the first wagon road to cross the Rocky Mountains and link the Pacific Northwest with the eastern states.

Prichard would go on to make another gold discovery in 1882. He was unable to keep his 1882 discovery a secret and by 1883 a rush of miners were entering the area in search of riches. This initial gold rush centered in areas north of Wallace and the camps of Murray, Prichard, Eagle City, and others sprang up during that year.

In 1884 the first silver discoveries were made at locations that would become the communities of Burke and Mullan, not far from the future site of Wallace.

Early in 1884 Colonel William R. Wallace built a cabin at an open area in the valley where several streams converged on the South Fork of the Coeur d’ Alene River. The location was one of the only flat spots for building in the rugged mountainous region, and was central to many of the gold and silver discoveries in the area. The site would become known as Wallace, and would grow to be premier mining city in a spectacularly wealthy mining district.

The mines of the Coeur d’ Alene District needed major improvements in infrastructure and transportation routes to become feasible. The first narrow gauge railroad into the valley was built in 1886 and reached the town of Kellogg. By 1887 the line was extended another eleven miles to Wallace.

With the arrival of the railroad, mills and smelters could be built on a large scale, and the district was transformed into a major producer of silver and lead.

The mines of the district were large industrial operations that employed many men, and as is often the case with such operations, conflict between labor and mine owners was inevitable. The first labor unions were organized in the late 1880s, and in response the mine owners formed the Mine Owners Association to present a united front against the unions.

The first miners strike occurred in May of 1890 at the Tiger-Poorman mine. The miners complained of poor food at the mine boarding house and demanded improvements, resulting in a five day work stoppage.

Tensions between the unions and the mine owners would continue to escalate over the next few years, with periodic strikes increasing in size and consequence. The situation culminated in July of 1892, with 400 union members taking control of several area mills and threatening to blow them up if mine owners did not give in to their demands.

Martial law was declared in the district and by July 15 1,500 soldiers were camped in the valley and charged with restoring order. Five men were reported killed during the unrest. The district became quiet again but similar episodes of labor unrest would occur many times in the coming years and decades.

By 1898 over 1,200 men worked in the Coeur d’ Alene District. That year the county seat was moved from Murray to Wallace, which had become the center of a vast mining empire.

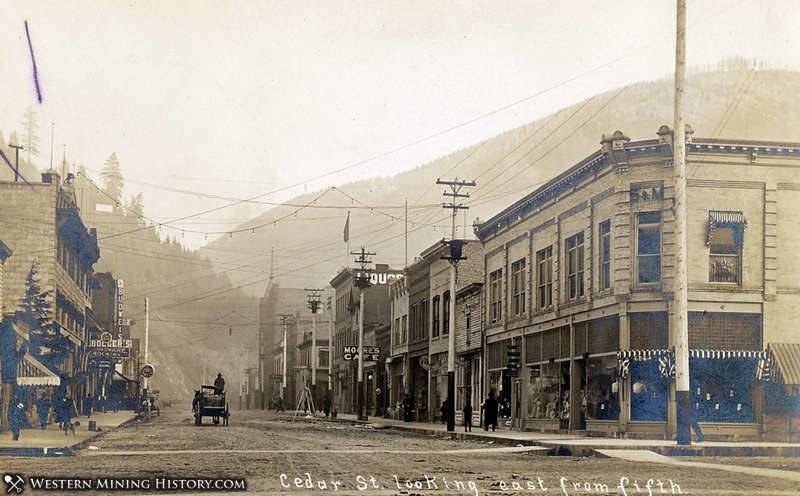

The first decade of the 1900s saw Wallace in the midst of a great boom. The city had thousands of residents, many paved streets, an electric light system, and hundreds of homes and buildings.

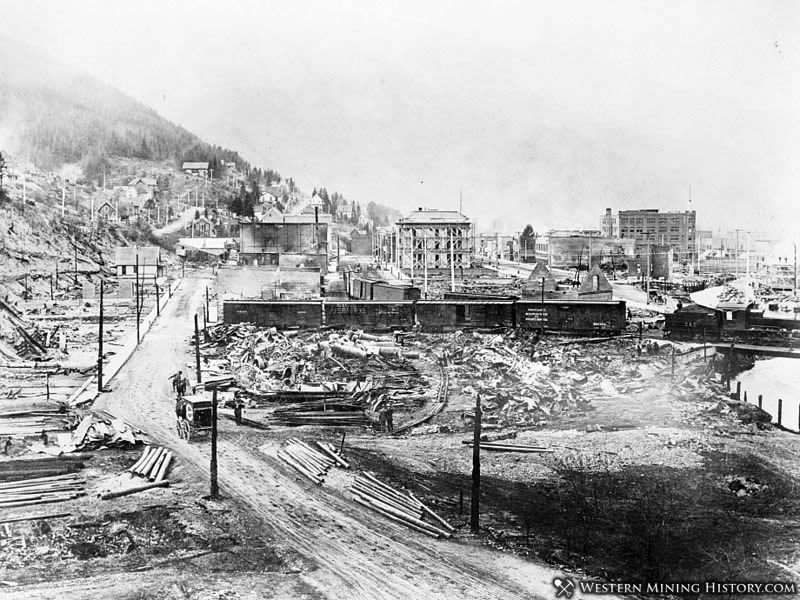

The Great Fire of 1910, a wildfire that ultimately burned over 3 million acres of forest, burned down a third of the city of Wallace and caused heavy damage to almost every town in the district.

Demand for lead during World War I would get Wallace back on its feet however as the lead-silver mines of the Coeur d’ Alene District supplied much of the lead needed for the war effort.

The mines of the Silver Valley were extensive and deep, and demand for silver, lead and zinc kept the district prosperous through both World Wars and through the 1960s and 1970s.

Concerns about pollution and passing of air quality laws were putting pressure on the mining industry. The 1981 closure of the massive Bunker Hill smelter in Kellogg was a devastating blow to the local economy, with as many as three-quarters of all regional mining jobs being lost.

Wallace was notorious for its red light district. Even as late as the 1960s up to 60 women were still working in the local brothels. A New York Times article from 1973 describes the sudden closure of 5 brothels for political reasons, “the first shutdown of brothels in Wallace’s history.” The last brothel in Wallace closed in 1990.

Wallace was notable in that it was the site of the last traffic signal light on Interstate 90, which spanned over 3,000 miles across the nation. A new bypass was built and the light was removed in 1991.

While Wallace has transitioned to a post-mining economy that includes recreation and tourism, the local mining industry is still active with at least one major mine still in production. The Silver Valley is likely the longest producing mining area in the United States, and one of the most important districts in the West.

Today several blocks of Wallace’s downtown are preserved as the Wallace Historic District. Wallace is one of the West’s best-preserved mining cities and is a must-see destination for anyone interested in mining history.

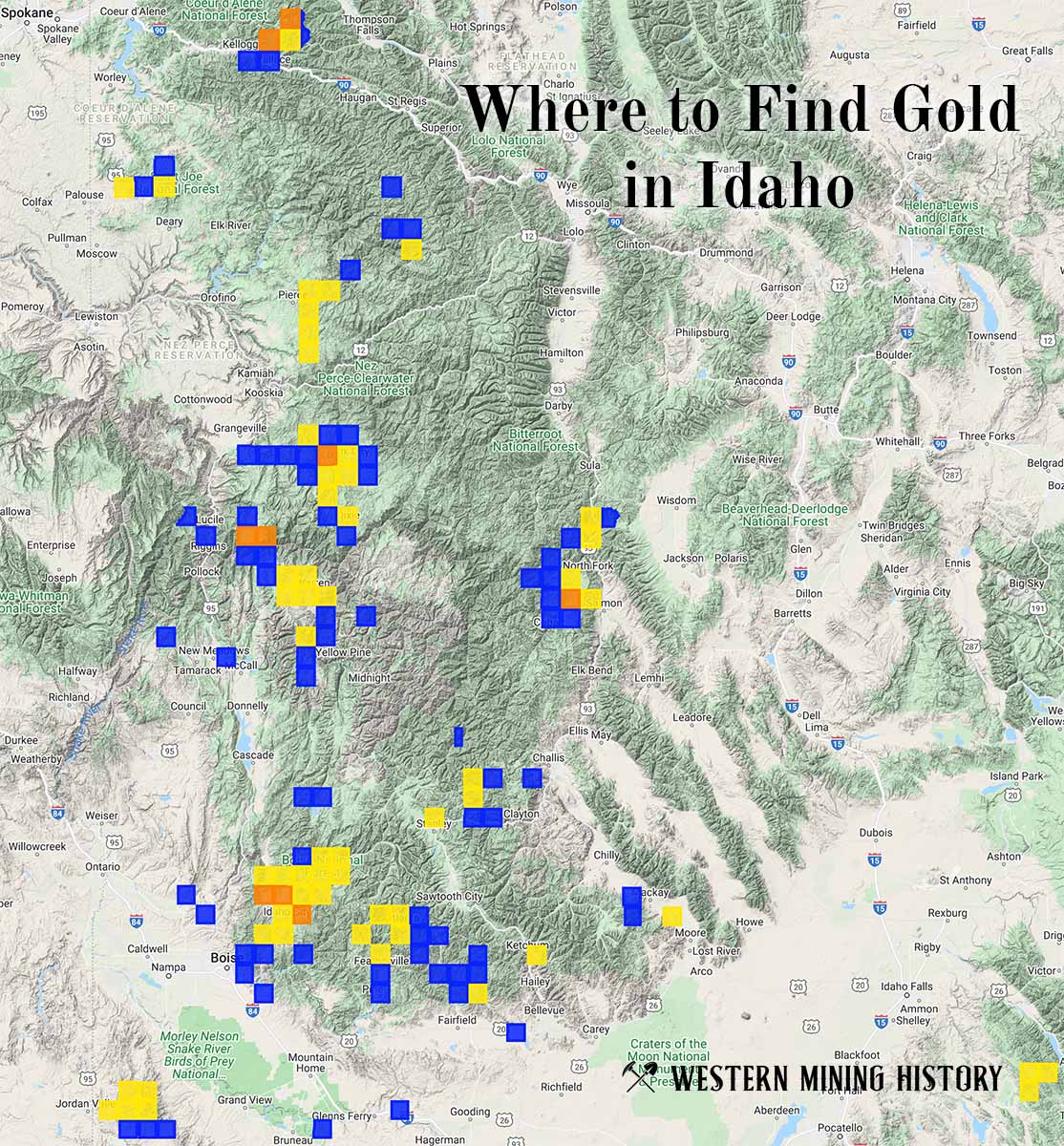

Idaho Gold

"Where to Find Gold in Idaho" looks at the density of modern placer mining claims along with historical gold mining locations and mining district descriptions to determine areas of high gold discovery potential in Idaho. Read more: Where to Find Gold in Idaho.