Hot Creek History

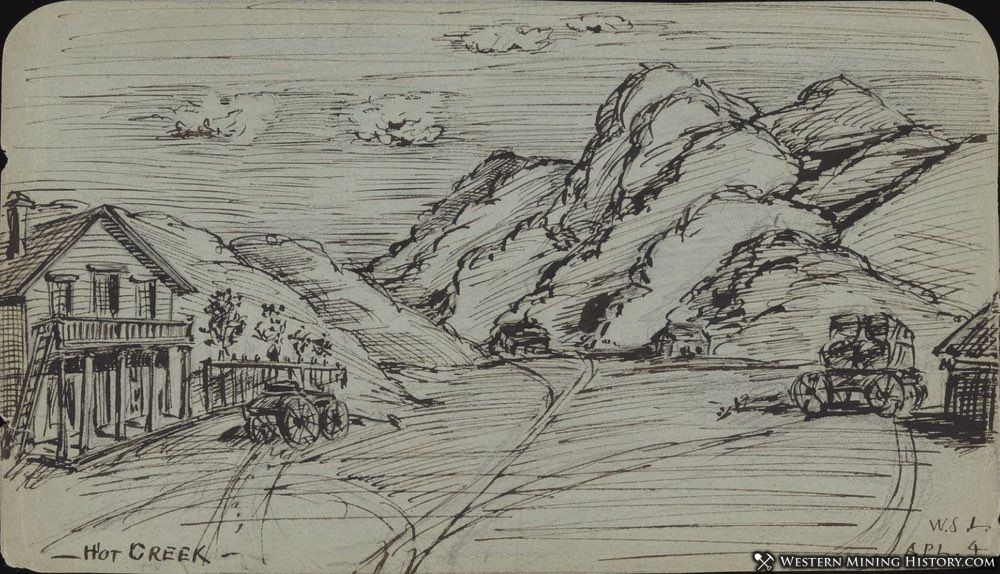

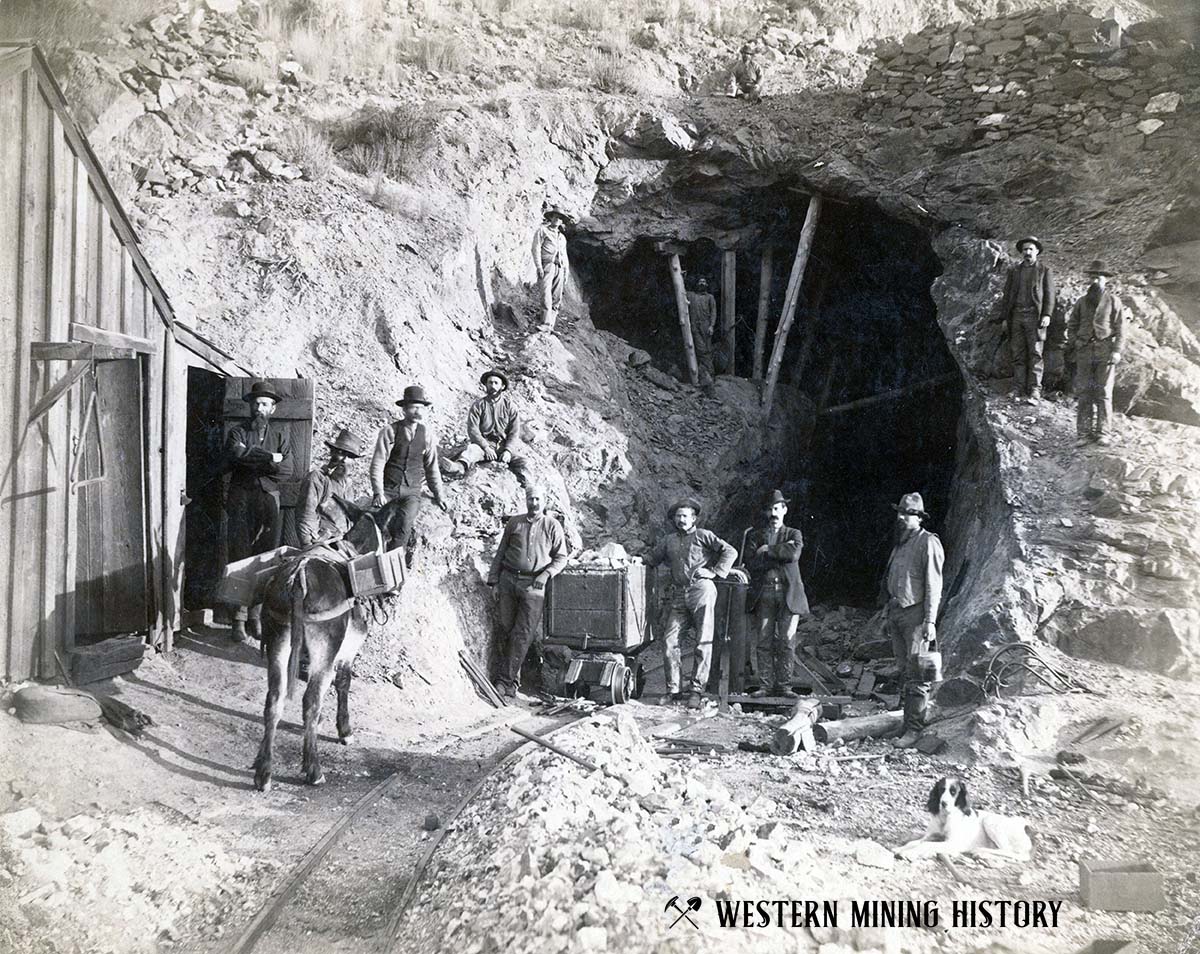

Hot Creek is unusual among the mining ghost towns of Nevada. Founded in the 1860s, the town was both a mining camp for nearby mines and an important stop for freight stage traffic to nearby mining centers like Tybo. The unusual part is that Hot Creek was also a minor resort town deep within one of Nevada's most isolated regions.

Like the name implies, Hot Creek was built near hot springs, and in the 1800s these springs became a popular retreat for residents of nearby mining camps. An unusually ornate hotel was built in the town to serve tourists visiting the area.

Not much is known about the settlement, but an 1869 newspaper article mentions increased interest in the mines near Hot Creek:

A letter from Hot Creek, Nevada, published in the last number of the Mountain Champion, Belmont (Nev.), states that some of the miners of that place who had migrated to White Pine, are returning to their claims at Hot Creek, after having verified the old adage of "going further and faring worse."

The 1951 publication Mineral Resources of Nye County, Nevada by the Nevada State Bureau of Mines includes a paragraph about Hot Creek:

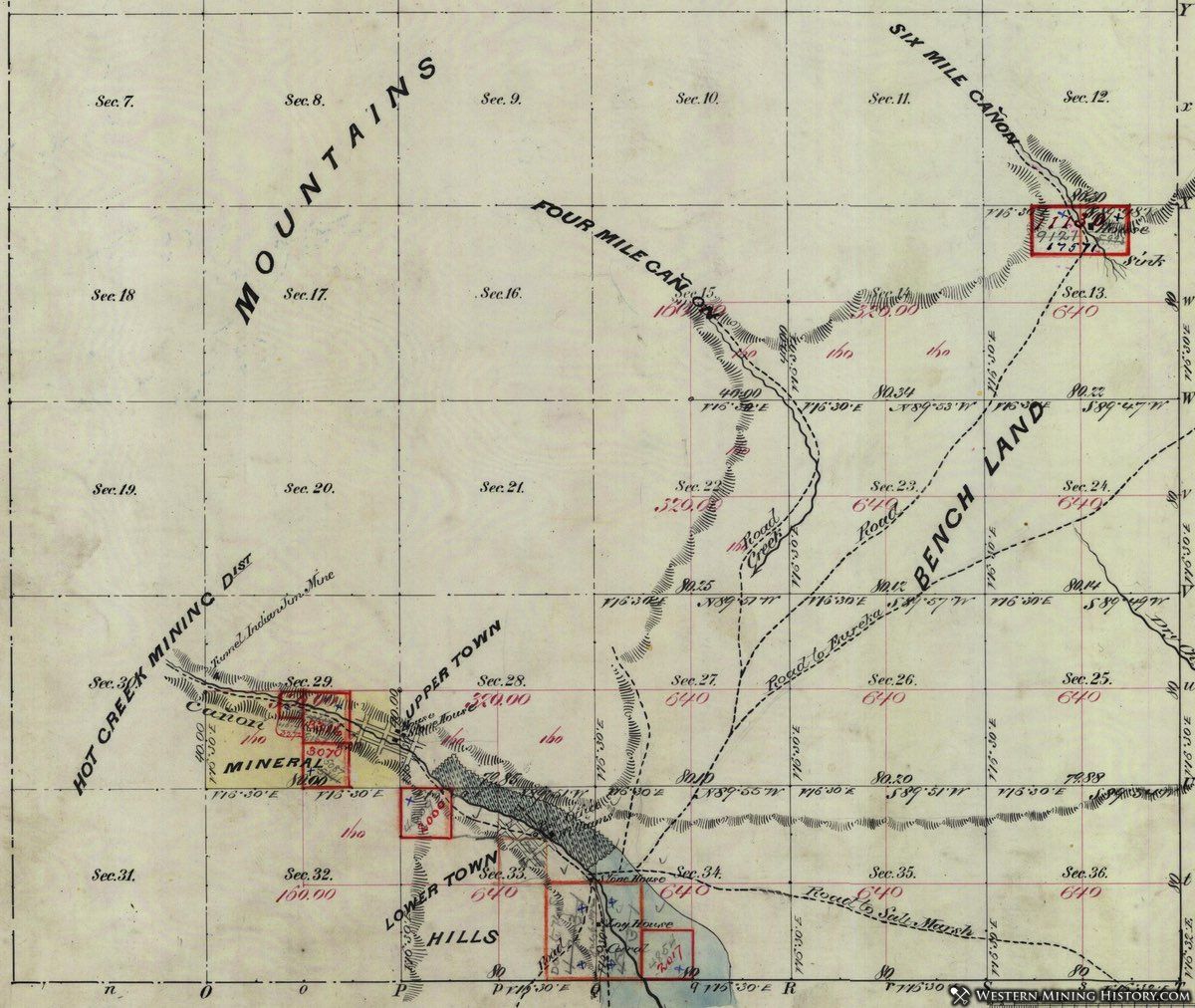

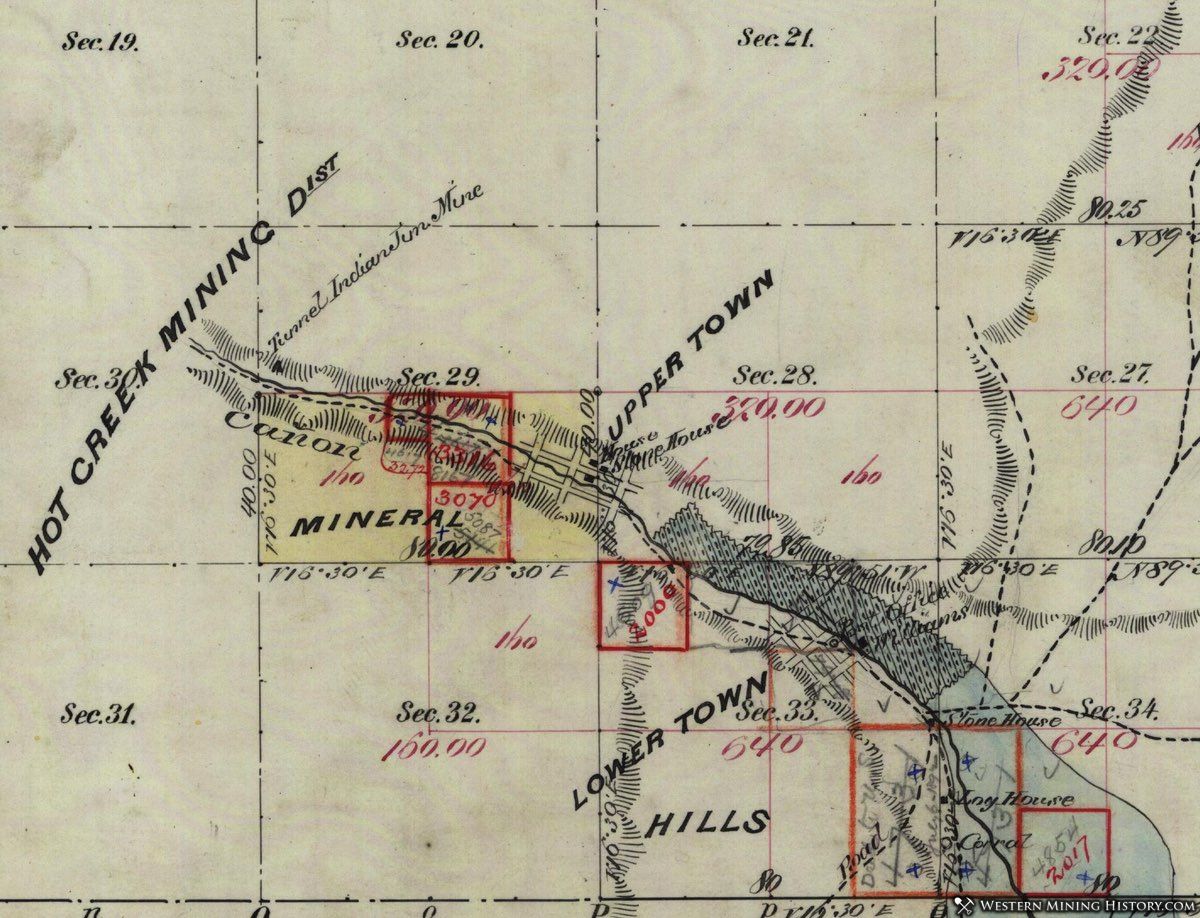

The town of Hot Creek was apparently quite active in the early days. Thompson and West state that it was divided into an upper and lower camp and each had a stamp mill, although neither mill operated much. The town was the property of J. T. Williams and was the site of a very elaborate stone building. This building, later gutted by fire, was restored in the early 1900's; it still stands at Hot Creek. It is said that Williams made a sizeable stake from an early discovery in the Danville district, with which he purchased and improved the Hot Creek site. The town is reported to have had a population of 300 in 1868, but is said to have dropped to 25 in 1881.

Records indicate that Hot Creek had a post office from 1867 to 1881 and from 1897 to 1912. At some point the town of Hot Creek was abandoned and the site became known as the Hot Creek Ranch. It is likely this occurred in the period between post offices 1881-1897. The hotel survived as the ranch house and still stands to this day.

While the date that the town became a ranch is not known, a December, 1909 issue of the Los Angeles Herald article titled "Hot Creek Ranch House, A Famous Nevada Home" verifies that it was a ranch by that year. Interestingly, the title of the article also reveals that the old Hot Creek hotel was a famous building at the time. Unfortunately the article doesn't actually talk about the structure at all, but has a few interesting quotes related to the owners of the ranch and their history with the Nevada mining industry.

Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Williams of Hot Creek, Nevada are in Los Angeles to pass a portion of the winter, and are guests at the Rosslyn.

Mr. Williams is the oldest male resident of Nye county, Nevada, barring a few stray Indians, and has played an important part In the reclamation of a portion of the desert country, the development of the mineral resources and in waging a fight against the railroads, which for years controlled the state. As a member of the legislature he was the author of the Williams resolutions which were sent to congress as a protest against the dominance of the roads.

Mr. Williams was an associate of Fair and Mackay in the palmy days of the Comstock, going to Nye county to reside in 1866. With Mrs. Williams, who is a fitting helpmeet for a man who spends his life on the frontier, and one of the most lovable women in the world, he has reared a family on his beautiful home ranch, which is the stopping place for every wayfarer who travels the road. He is familiar with all of the well known mines in that region, and knows every prominent mining man in the state, including Jim Butler, who discovered Tonopah.

Nevada Mining Photos

A Collection of Nevada Mining Photos contains numerous examples of Nevada's best historic mining scenes.

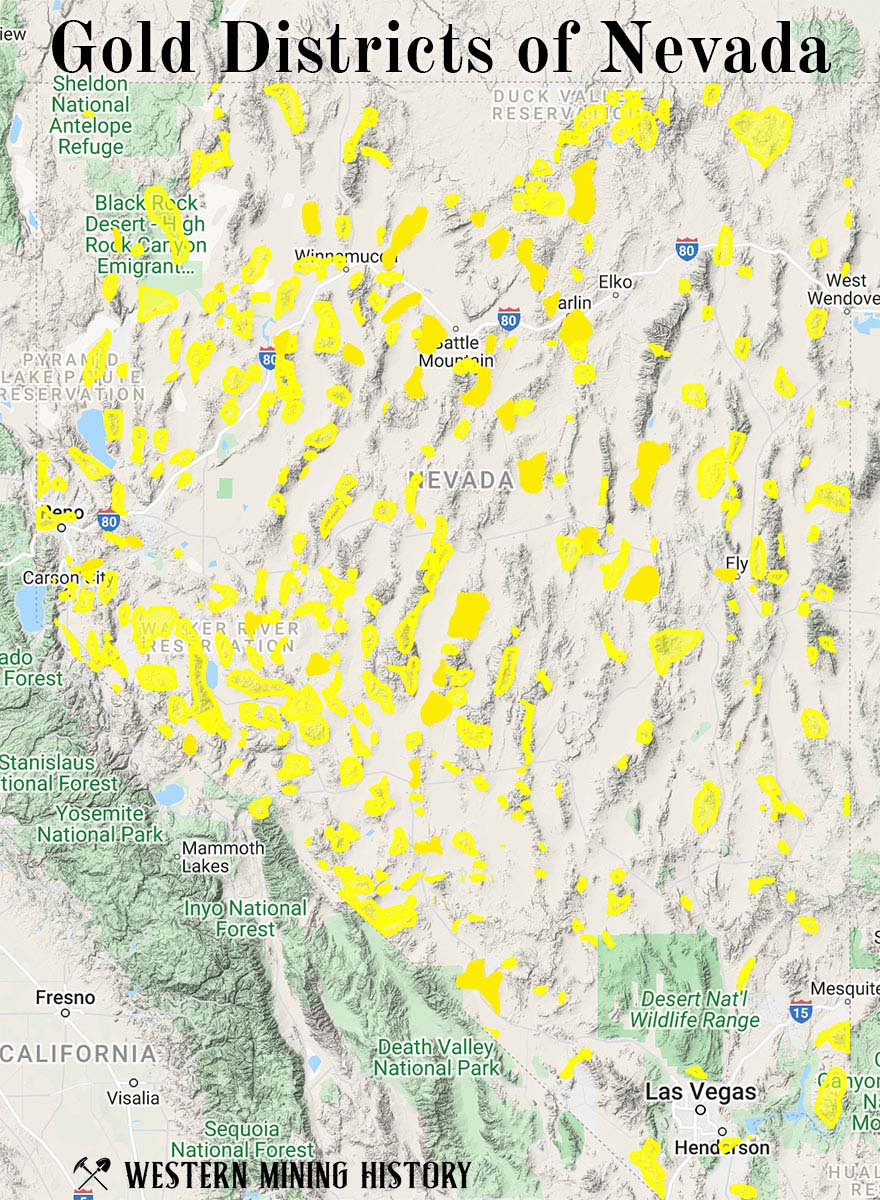

Nevada Gold

Nevada has a total of 368 distinct gold districts. Of the of those, just 36 are major producers with production and/or reserves of over 1,000,000 ounces, 49 have production and/or reserves of over 100,000 ounces, with the rest having less than 100,000 ounces. Read more: Gold Districts of Nevada.