The hanging flume is is a five mile section of wooden flume that was built on the sheer cliffs of the San Miguel and Dolores Rivers in the canyon country of western Colorado. Built over a three-year period from 1888 to 1891, the flume was 150 feet or more above the canyon floor and was built at great cost, but the mining venture it supplied water to was ultimately a failure.

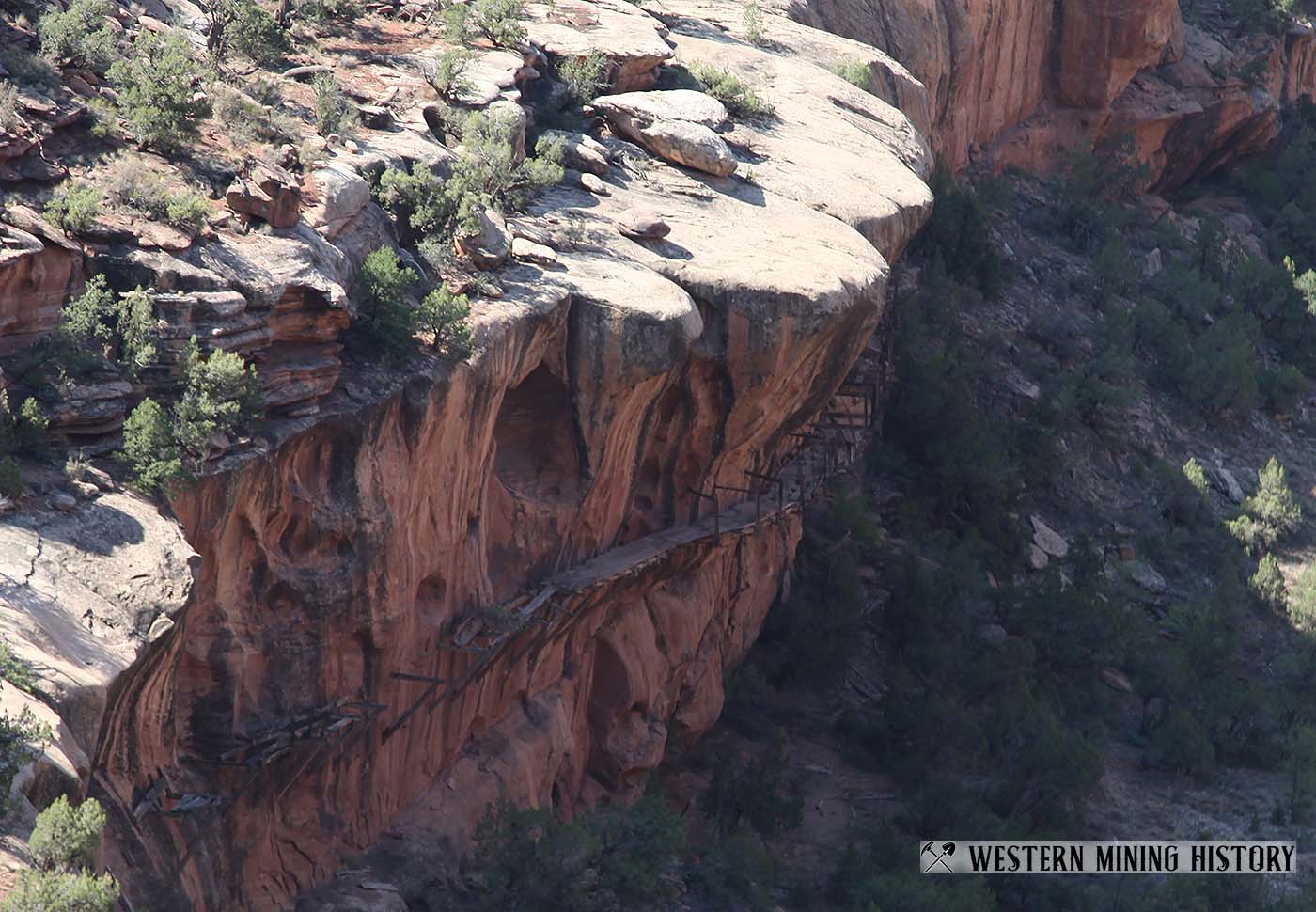

The combination of the dry climate in this part of Colorado, and the extremely difficult placement of many of the flume sections which has deterred vandals and scavengers, has resulted in many segments surviving, although greatly deteriorated, for almost 130 years.

“Its construction dazzled mining pros with its sheer ingenuity”

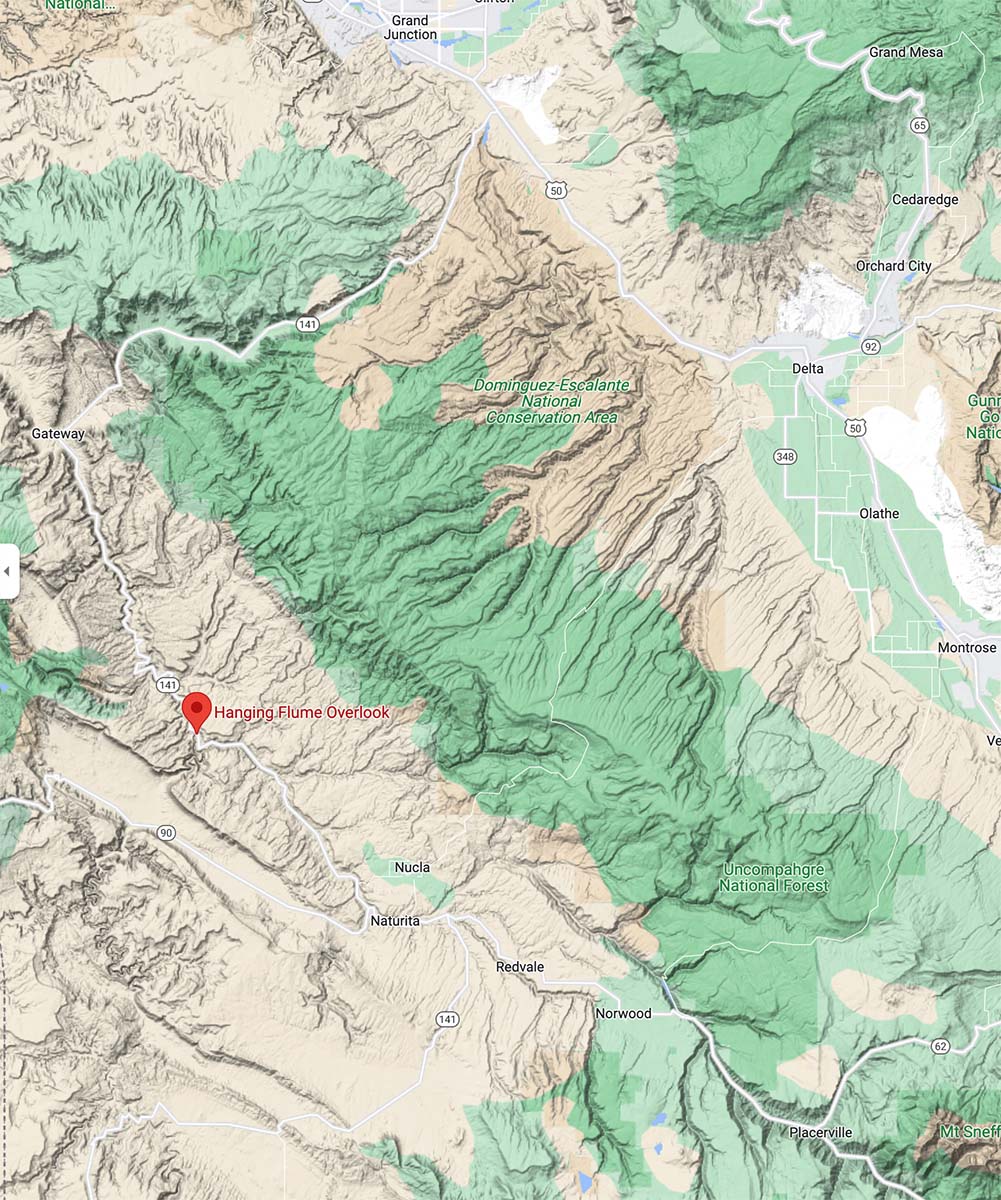

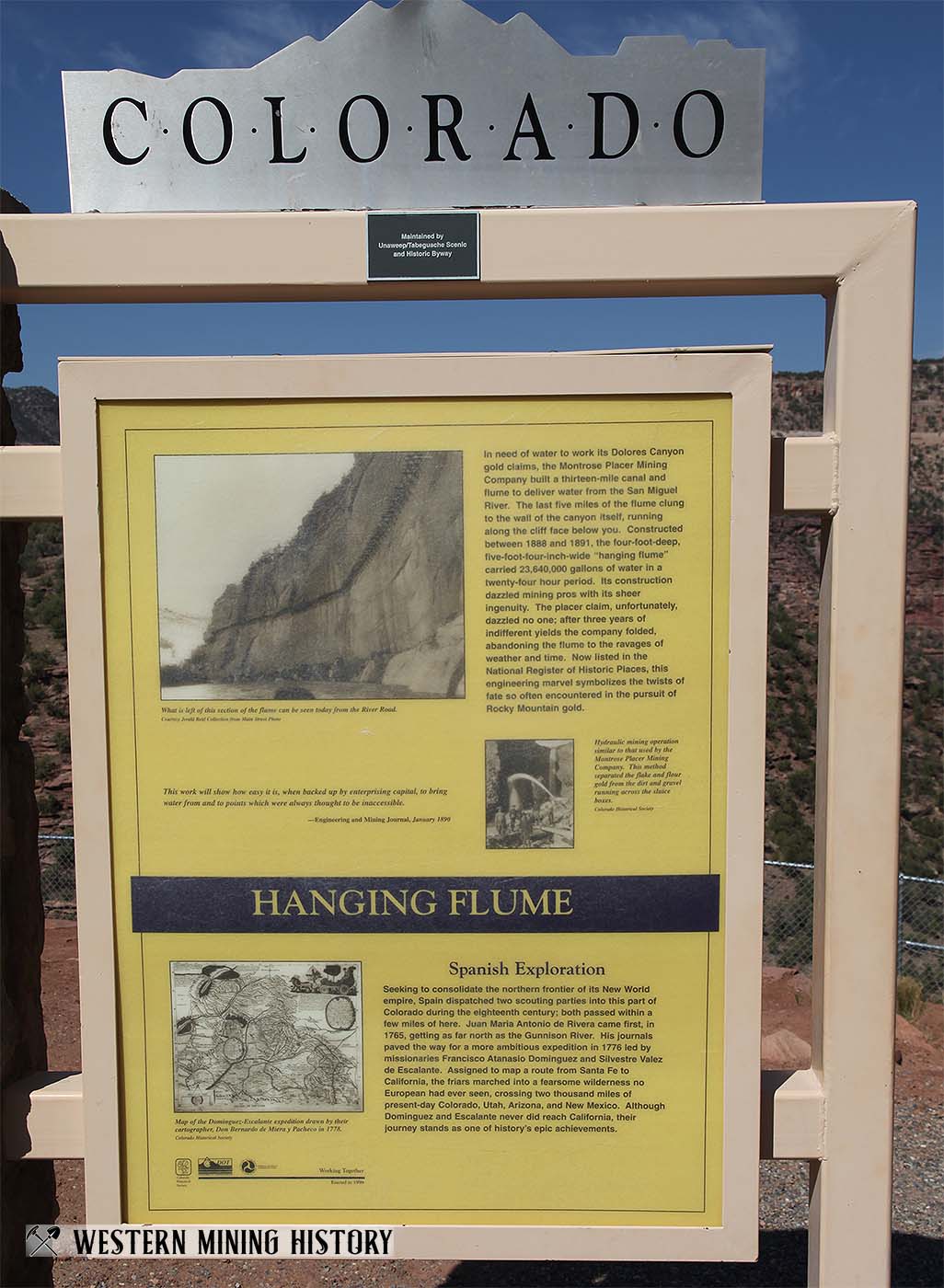

An overlook and interpretive site on highway 141 provides a view of the flume and several interpretive signs that convey the history of the flume and recent efforts to preserve the history of this amazing structure. The following quotes are from the interpretive signs at the overlook.

In need of water to work the Dolores Canyon gold claims, the Montrose Placer Mining Company built a thirteen-mile canal and flume to deliver water from the San Miguel River. The last five miles of the flume clung to the wall of the canyon itself, running along the cliff face below you.

Constructed between 1888 and 1891, the four-foot-deep, five-fooot-four-inch-wide hanging flume carried 23,640,000 gallons of water in a twenty-four hour period. Its construction dazzled mining pros with its sheer ingenuity.

The placer claim, unfortunately, dazzled no one; after three years of indifferent yields the company folded, abandoning the flume to the ravages of weather and time.

Now listed in the National Register of Historic Places, this engineering marvel symbolizes the twists of fate so often encountered in the puruit of Rocky Mountain gold.

The Flume was built by lowering lumber from the top of the cliff with winches and cables. Men worked from “bosun’s chairs” that were hung from ropes. Lumber had to be cut and milled many miles away and hauled over crude roads and then trails to each staging point along the canyon rim.

An 1890 edition of Engineering and Mining Journal made an ironic statement regarding the construction of the flume:

This work will show how easy it is, when backed up by enterprising capital, to bring water from and to points which were always thought to be inaccesible.

The work required to complete this difficult project was anything but easy. Today the hanging flume is regarded as an amazing feat of ingenuity and determination by the men who built it so long ago with nothing but crude tools and in a very remote region that was both difficult to access and extremely rugged.

The flume only operated for several years as the fine gold proved to be too difficult to separate from the river gravels. Decades later, much of the wood was scavenged to build homes during the uranium mining boom.

Much of the flume was located in such challenging canyon terrain that even determined scavengers could not tear it all down. Today the flume is regarded as a historic wonder and in 2006 was placed on the World Monuments Fund`s “100 Most Endangered Sites” list.

In 2012, in a project funded by the Colorado State Historical Fund, forty-eight feet of the flume was reconstructed with the goal of gaining better understanding of how the flume was built in the 1890s.

There is still much interest in preserving Colorado’s amazing hanging flume and hopefully enough will be preserved so that future generations can witness firsthand this wonder of ingenuity from a bygone era.

The Hanging Flume of the Dolores

A Unique Engineering Accomplishment

This article by Douglas D. Scott was published in “Your Public Lands” in 1983 – a publication of the Bureau of Land Management.

Since 1859, gold has lured men to the mountains and streams of Colorado. The desire to find and recover gold in the mountainous regions of Colorado has required miners to employ new, and often ingenious, methods to extract this precious resource.

In 1887, the Montrose Placer Mining Company bought six and one-half miles of placer gold mining claims on the Dolores River in west-central Colorado, an event which triggered the construction of a unique engineering feature-the hanging flume of the Dolores.

The placer miners prospected the Montrose claims in the fall of 1887 and during the spring of 1888. Their panning yielded a good show of gold, but it became obvious that traditional methods of extraction would not be profitable. The superintendent, N.P. Turner, along with several other individuals concluded that, if enough water could be brought to the Mesa Creek Flats claims area, hydraulic mining procedures could be effectively and profitably employed.

The Dolores River had more than an adequate water supply. The problem was how to get enough pressure and water to Mesa Creek through the winding, precipitous, deeply entrenched Dolores River Canyon that had only limited access. To Superintendent Turner the answer was simple enough; build a ditch and flume system along the Dolores to Mesa Creek and then extract the millions in placer gold that awaited the innovative entrepreneur.

And construct a flume they did! The remnants of the hanging flume still cling to the walls of the Dolores River Canyon and they are considered such a significant engineering feat that the hanging flume was placed on the National Register of Historical Places in 1980.

According to the Engineering and Mining Journal of May 17, 1890, the flume was begun in 1889 and constructed in the following manner:

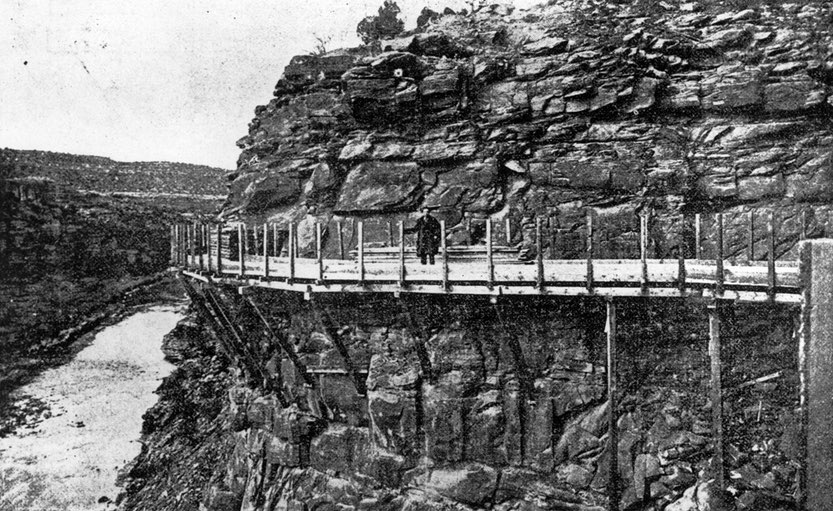

There is about half and half ditching and fluming, and the latter has a fair claim to be considered a fine piece of engineering work, the flume being suspended on brackets and on benches. The total costs will be about $75,000 when finished, and it is expected to be completed within a few months.

This work was commenced at the lower end, where the greater part of the flume is. This was done for the reason that the forest from which the lumber was obtained is located nearest that point. Now work is going on at the upper end where the river is tapped, floating the lumber down the flume to where it is required.

By this means it is hoped to have everything tight and no leakages to give trouble when hydraulicking is commenced. This work will show how easy it is, when backed up by enterprising capital, to bring water from and to points which were always thought to be inaccessible.

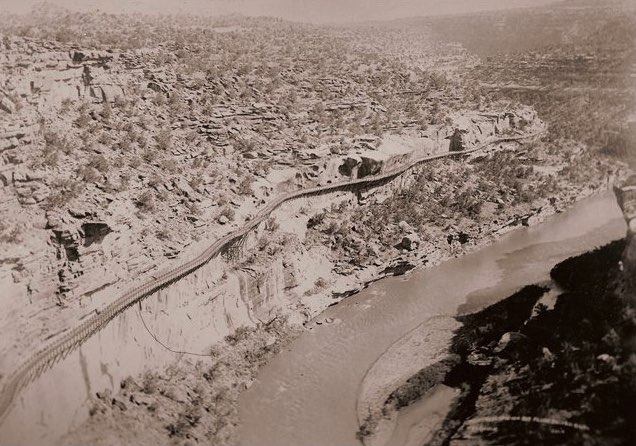

The flume traverses the whole length of the Dolores Canyon which is almost four miles. It is fastened to the walls of the cliff, and for a long distance is at an elevation above the river of 300 to 400 feet. It is very firmly built and has been fully tested to carry the volume of water which will pass through it when finished.

At a number of places the lumber has been piled in the flume as high as 13 feet and additional weight added to it without any noticeable variation. A large rock weighing many tons fell from the top of the cliff and only tore off a small section of 20 feet. It snapped off the heavy timbers as if they were matches, without loosening or even straining the supports a few feet further on. The break was entirely and fully repaired in two hours.

The lumber is clear mountain pine, the wide boards and dimension pieces running full length, without sap and with very few knots. It is all well seasoned before being used.

In getting the levels the work was very dangerous, the man being lowered down over the cliff over 50 feet, marking in red paint the line to be followed by the construction gang. As the supporting timbers were put in place, the floor of the flume was laid and the derrick pushed out ahead, from which other supporting timbers were raised and secured to their places.

Under favorable conditions and with a gang of 12 men, 250 feet per day have been erected. At one point on the line, nearly 200 feet long, the rock projects out, forming a sort of canopy, and is so shaped that it was impossible to support the flume on brackets, and it is hung from bolts, driven in overhead, on which the flume swings.

In making the survey for this work the nature of the country necessarily made it a very difficult operation, as most of it had to be done by triangulation. It is very creditable to be able to state that no mistakes were made except slight ones, which were easily corrected.

The flume is fastened to the cliff… The bolt is 1-1/4 inch in diameter, and is driven in the rock 18 inches, the shoulder which supports the weight being first bent to shape at the blacksmith shop. The long brace at the bottom rests on a shelf-natural, if it can be found, otherwise one is cut, and the pin is driven through this brace into the rock, and thus prevents it getting loose.

Wilson Rockwell, author of Uncompahgre Country, obtained additional information of the construction and use of the flume system from local residents. According to Rockwell, the mining company established a sawmill in San Juan County, Utah, to cut timber for the flume. The lumber was hauled by six-horse-hitch wagons to the building site along the Dolores.

Most of the lumber was two-inch pine boards. Approximately 1.8 million board feet of timber were used in the construction of the four-foot-deep, six-foot- wide, three-sided flume.

The flume was supported by brackets on the cliff walls high above the river and from 250 to 500 feet below the summit of the gorge.

In building the flume bed along the side of the cliffs, an improvised flat car was used with a long crane attached to the front of it. This car was pushed on improvised railroad tracks along the flume bed, and the crane in front was used to hold the workmen out over the canyon wall while they drilled holes into the face of the wall to insert the iron brackets on which they would build the flume.

When one joint was completed, the tracks on the flume bed would be extended and the flat car with its platform pushed forward to construct the next joint. The rear of the car was loaded with rocks to weight it down while the crew was was working out over the cliff on the crane.

Where the bluff was straight enough with no overhanging walls, men were dropped over the side in “bosun” chairs to drill the holes, insert the braces, and lay the flume. One of the “bosun” chairs can still be seen in rockshelter on the Dolores River that served as one of the campsites for the laborers.

The lumber for the flume was pulled up from the bottom of the canyon with ropes, or lowered down from the top of the canyon, depending on which way was more feasible. In the deepest part of the canyon, where it was impossible to get a wagon and too far to swing the lumber over the top, the building material was floated down the river on a barge and then pulled up by the ropes to where the men were working.

Local labor of about 25 individuals was used in the construction of the project. According to Wilson Rockwell the laborers were paid $2.50 per day plus board. Legend has it that Chinese coolies were the primary labor source and that substantial numbers of them were killed during the undertaking. As with most legends, there is a grain of truth in it but only a grain. There was one Chinese on the project and he was the cook. There was also one man killed, the but he drowned while swimming in the river.

It took over two years and more than $100,000 to complete the hanging flume. The project was completed during the summer of 1891 and on the day water was turned into the flume all the cowboys and miners in the area came to see the big event, or so the story goes.

From an engineering perspective the flume was a complete success. The flume carried 80 million gallons of water over a 24 hour period and fell in a grade of six feet, ten inches to the mile over an eight-mile length.

Unfortunately, the mining operation was not as successful. The placer gold in the river is an extremely fine flour gold and could not be extracted by hydraulic pressure. The gold washed right through the sluice boxes.

Superintendent Turner thought the liberal use of quicksilver (mercury) as an amalgam was a cure, but even the quicksilver could not hold the gold. By the fall of 1891, the project was an obvious failure. According to legend, Turner, on a promotional trip to Chicago, killed himself over the failure.

The flume was shut down in 1891, the same year it was finished, and the local ranchers and farmers salvaged as much of the lumber as possible for use in constructing sheds, and other ranch out-buildings.

The remaining portions of the abandoned flume began their slow decay, but some of the skeletal remnants of the enterprise still cling to the walls of the spectacular Dolores River Canyon for the modern passerby to see.

The Hanging Flume, located on BLM-administered public lands in southwest Colorado has been placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Colorado Mining Photos

Check out this collection of Colorado’s best historic mining photos: Incredible Photos of Colorado Mining Scenes.