By Gary Carter

Early History of the Vulture Mine

The Vulture Mine, near Wickenburg, Arizona could be the central character in a dime novel. Its myths, legends, and facts have and continue to stir the imagination. Stories of ghosts, men, and animals lost in the “Glory Hole”, Indian attacks, bullion robberies, gold fortunes, lost veins, and personalities as grand and sweeping as the desert winds are part of Arizona history.

Wickenburg fell one vote short of being named the territorial capitol. Jack Swilling, one time mine and mill owner, addict and hero is noted as the Father of Phoenix. HAW Tabor, the legendary Silver King from Leadville, Colorado, once owned the Vulture and later said it was the worst mining decision he ever made.

Michael Goldwasser (aka Goldwater) the grandfather of famous Arizona politician and presidential candidate, Barry Goldwater, had an early lien on the Vulture. Michael and his brother were prosperous businessmen and in the early days loaned the Vulture $35,000 to buy water pumps and continue operation. The money was quickly paid back and the Goldwater brothers eventually operated successful businesses in Phoenix and Prescott. Michael became the founder and first president of the Arizona Democratic party!

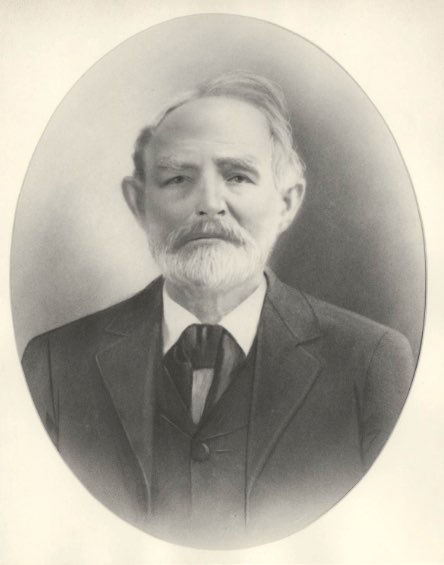

After President Polk formally announced that the rumors of rich gold strikes in California were real, a grand exodus from the East Coast and Europe began with the destination being California’s gold fields. Easterners braved the long overland trek by wagon and Europeans braved the ocean voyage around the Cape to reach the port in San Francisco. Henry Wickenburg, a Prussian by birth, is first noted in some of the Mother Lode gold towns around 1852, probably too late to get in on the easy, early placer locations.

There was no Phoenix, no Flagstaff, or Prescott. Most of the population was Mexican and most were in Tucson. Indian tribes abounded with the notorious Apaches creating the most fear. Roads were basically nonexistent. As the easiest of the gold gathering in California began to play out miners gradually moved toward Southern California, then through Yuma and up the Colorado or into Arizona—still seeking riches.

Henry Wickenburg was to sign on with an expedition founded by A. H. Peeples and led by an old Southwest scout, Paulina Weaver. The group of about 30 crossed the Colorado River into Arizona Territory in the spring of 1863 and headed east, prospecting as they went. They eventually stumbled onto one of the richest surface finds of gold then known.

At what is known as Rick Hill, in Central Arizona they found nuggets, flakes and pieces of gold that could be dug out with spoons, knives and picked up with the hands. A nearby town was named Weaver for the early explorer. But the surface gold was soon depleted and while some remained to dry wash, others moved on to the nearly contemporaneous strike near Prescott in the Walker Mining District.

Henry Wickenburg and two companions, Isaac Van Bibber and Theodore Green (aka Rusk), took advice from an early pioneer, King Woolsey, who was in the area. Woolsey suggested they travel to the Harquehala Mountains where a decent gold strike had been made. The three, traveling by following streams and trails reached the Harquehala’s but came up empty. On their return trip, they noticed a conspicuous quartz outcropping but continued back to camp along the Hassayampa River near present day Wickenburg.

In November of 1863, the three put up a location notice but failed to do much more. Wickenburg remained camped along the river, some 15 miles from the strike while Green, having samples of the gold quartz, left for Tucson, his home, and Van Bibber’s set off for California to obtain financing and supplies. In May of 1864, Henry Wickenburg and four different men went back to the claim and officially filed on it and at the same time organized the Vulture Mining District, with Wickenburg as President and a James A. Moore, a businessman, as recording secretary.

First work on the Vulture was by pick and shovel and basically amounted to quarrying the exposed gold quartz lode. Early estimates from unofficial records indicate 20 troy ounce per ton gold. Later, in litigation, filed under Murray vs. Wickenburg and associates (Murray and Roberts had bought, from Green, what they felt was his one-third share), Henry Wickenburg claimed that the Vulture was yielding $700 a day! (Gold prices in the 1860’s ranged from $20 to $47/ounce). The claim was heard by Judge Joseph Allyn who found in favor of the Wickenburg group. Ewing Van Bibber was later paid $10,000 to “Quit Claim” by subsequent new owners.

Despite the prosperous find, problems arose. Distance from water for mining and milling, lack of knowledge of even simple arrastra and mercury recovery, transportation shortcomings, Indians, lack of good labor, theft, and lack of mining and milling know how plagued the mine from the start. Eventually arrastras were put up along the Hassayampa River some 15 miles distant.

Wickenburg began selling ore for $15 a ton plus a royalty for anyone who would dig, load, and transport ore to the river, build and work an arrastra. Once word was out the area was trampled by prospectors looking for another Vulture. Claims like The Dinosaur, Turkey Buzzard, Apache, Harriet’s Wall, and my favorite, The Whopper were all recorded within six months. None ever proved productive.

Within two years of discovery, Henry Wickenburg and the other claimants sold most of their original footage and The Vulture Mining Company, under East Coast auspices, took over. The town of Wickenburg grew and developed when mill sites were established along the river. Sites moved as the wood supply used to produce steam energy was depleted. In 1883, receipts indicate the mine and mill used up to 15 cords of wood a day.

Desert trees were cut for miles around the area. Freighters hauled in wood and supplies. Large mining equipment was floated up the Colorado to La Paz and then hauled some 150 miles overland to the Vulture. Wickenburg became the business and supply center of the area. Phoenix was still not viable as a town and Prescott, Tucson, and Yuma were the principal settlements.

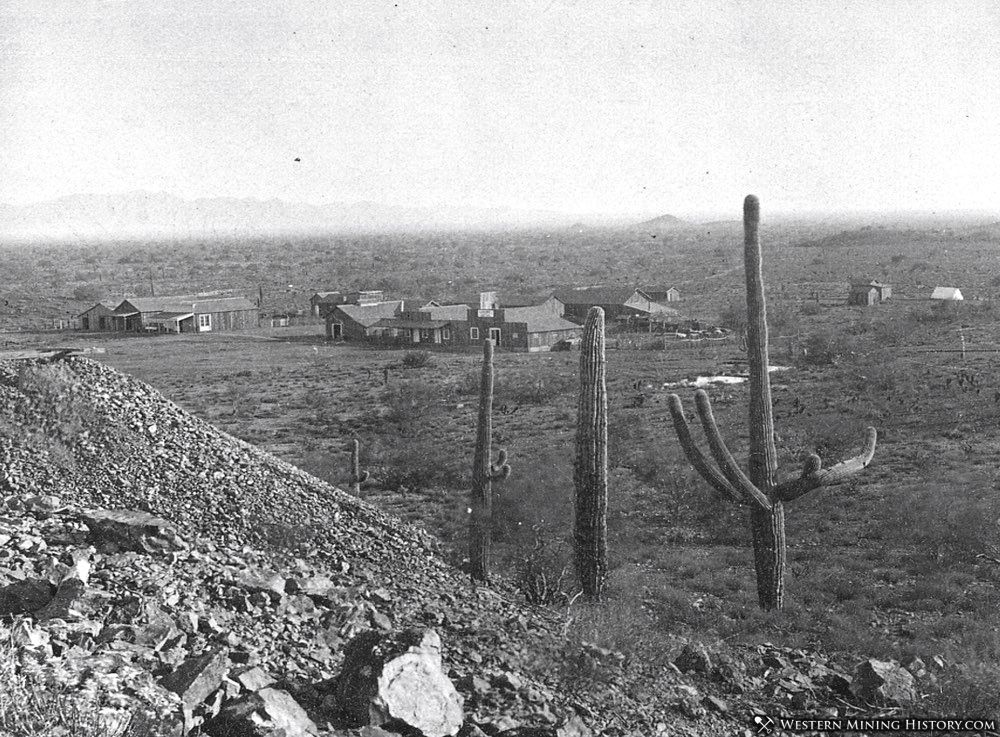

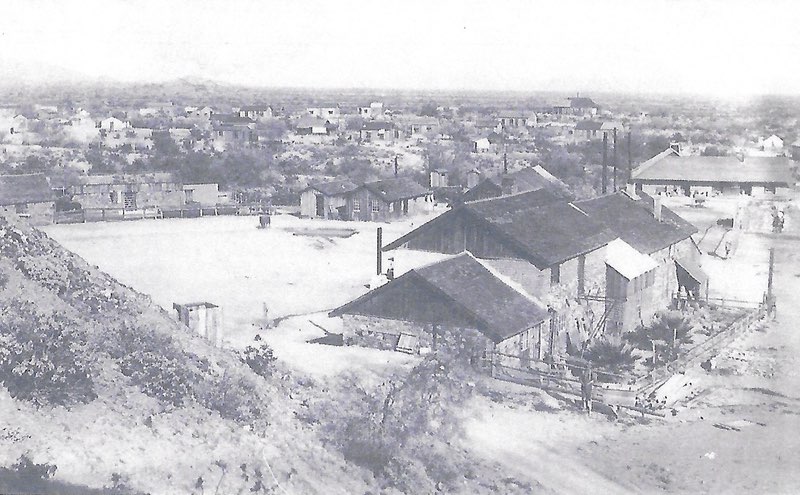

In the 1880s it was decided to build a 15-mile, six-inch pipeline from the Hassayampa River to the mine site. Expenditure of $2,400 a mile and six months of grueling labor accomplished the task—and water was delivered to the mine and mill site. Once water was available a small town, Vulture City (the first Vulture City was a mill site north of present day Wickenburg) grew and developed.

In 1890 the disastrous Walnut Grove Dam collapse flooded the river and destroyed much of the pipeline. It was never repaired but water from the 300 foot level of the mine and finally a well were in use on the property. Eventually the mill increased to 80 stamps, which ran day and night with a thunder that could be heard in Wickenburg on a clear and windless day.

Electricity came to the Vulture in the early 1900s, but until 1913 when their first truck was purchased horses and wagons for both mine and personnel transport were used. Miners and a few families began to settle at Vulture City. A school house, with two schoolmarms, operated from 1908-1915, but overall population seems to have never moved above 500.

Mexican miners, who made up the bulk of the work force, were forced to receive lower pay than whites doing the same work and their housing was segregated. The town of Wickenburg also had strict rules regarding blacks, Mexicans, Jews, and other nationalities. Unlike many mining towns the Chinese population was negligible.

While Wickenburg was the “big city”, its fortunes, as well as those of Phoenix, mirrored the doings at the Vulture. Numerous Vulture personalities eventually located in Phoenix, Jack Swilling got the idea of irrigating the area by opening up the old Hohokam Canals. Henry Wickenburg and others put money into the Swilling Irrigation Company.

Within a few years the area around what is now Van Buren and 32nd in downtown Phoenix became an agricultural center. Swilling later became the first postmaster of Phoenix and E.E. Kirkland, who once ran the Wells Fargo office at the Vulture, became the first postal clerk 1884.

Following the successful Swilling Irrigation Company, Charles T. Hayden who was involved in mining measures, established another irrigation company and grain storage in what is now Tempe. The Hayden Library and land for building ASU came from Hayden.

The Vulture Mine often went through long periods of shutdowns, startups, leases, and exploration activities. Faulting, mismanagement, low gold price, and high overhead accounted for much of the down time. At least twice the property was sold, for back taxes, at sheriff’s auction. Once the rich ores played out reworking of tailings became a prominent and lucrative undertaking.

While some underground mining of pillars and overlooked areas continued, the veins of profitable gold thinned and the lode lost by faulting, for the final time, in 1916. Numerous attempts to find extensions were unproductive. The last try was carried out in 1931 by “Rawhide “Jimmy Douglas of Little Daisy fame. After much conjecture and drilling, Douglas put down a 500’ shaft that was to intersect the faulted lost lode but it was a waste of money.

World War II to the Present

Shortly before WW II, Ernest Dickie and John C. Lincoln held the Vulture. Dickie was a good mining man and Lincoln had vision and money. Together they worked the Vulture into WWII. Common wisdom has it that the Vulture closed in 1942, never to reopen again, but that scenario is incorrect. Apparently the Vulture had obtained an exemption to mine during the war years, and state mining records indicate that as late as 1944 the Vulture was producing lead, minor copper and gold.

Soon after that Dickie and Lincoln left to take over the Bagdad Copper Mine. Lincoln was instrumental in developing the company town at Bagdad. Both combined to turn the mine from a marginal underground producer to a very productive open pit operation. The use of large haul mining trucks and new on-site refining contributed greatly to Bagdad’s prosperity. That mine is still in operation, primarily as a producer of “molly”. John C. Lincoln had a long life of philanthropy – not only at Bagdad but also Phoenix.

The John C. Lincoln Hospitals (one of which is at I-17 and 101) and his development and donation of land in the Scottsdale/ Paradise Valley area were two examples. He developed the original Camelback Inn (now the Marriott Camelback) and was instrumental in Arizona’s entry into the winter resort business.

From 1945 until 1959 the mine was idle or in limited production. At the height of the Soviet nuclear threat, Civil Defense Authorities considered using the mine to store emergency supplies in case of an attack.

During the early 1960s, Dr. George Mangun bought the property with the idea of building a Desert Science Center devoted to research in the biological and physical sciences. Apparently that dream never materialized as there is no record of any activity. L. Wayne Beal owned the property from 1970 until 2011 when it was bought by the current owner, Vulture Peak Gold LLC.

Until now the last large scale exploration and mining at the Vulture took place in the late 1980s under supervision of Don White and Ben Dickerson working for the Budge Mining Company. Don is perhaps the person who best knows the geology and mining history of the Vulture. Mr. Budge, a rich industrialist from Nottingham, England was a western aficionado and had a dream and a need to own a gold mine.

Budge mining instructed geologists and engineers to leave no stone unturned in looking for new gold leads at the Vulture. This included reworking tailings, placer search, drilling and exploring historical leads. The operation lasted several years and perhaps broke even but no new basis to warrant extensive mining was uncovered.

Perhaps the best, most succinct and up to date Geology of the Vulture Mine is the article of that name in the Vol. 19, No.4, Winter 1989, Arizona Geology. Basically, the mineralization at the Vulture is due to a late Cretaceous pluton of quartz porphyry that intruded earlier rocks. The dikes, faulting, tilting, and rotation caused numerous headaches for the miners. Free gold in quartz, silver, often with the gold as electrum, galena, pyrite, chalcopyrite, sphalerite, wulfenite, and minor copper mineralization occurred in the deposit.

Exploding Myths

Extensive research primarily using Arizona Mining Records, Arizona Historical Foundation collections, Sharlot Hall collections, and the Weekly Arizona Miner among nearly one hundred references has enabled the author to ferret out many myths, misconceptions, and exaggerations regarding the Vulture story. Listed here are a few of those “non facts”.

Henry Wickenburg was never in the Civil War, was born in Prussia (not Austria), and did commit suicide but probably from dementia or depression as he was not penniless.

The town of Wickenburg came about when James A. Moore, the recorder for the mining district, sent a letter to Federal troops asking for protection for miners. The letter had a simple return address of “Wickenburg Ranch.” From then on the area became known as Wickenburg.

Jacob Waltz, the Dutchman of Superstition Mountain fame, never worked at the Vulture Mine. His whereabouts from 1864 on can be traced, and there is nothing but hearsay to indicate that Waltz’s Lost Dutchman Mine gold came from the Vulture. Some of that notion may relate to the fact the Jacob Waltz was with Wickenburg in the Peeples-Weaver party and Waltz and Wickenburg both signed a miner’s petition asking for government protection from Indians.

The origin of the Vulture name is still in doubt. It is unlikely that Henry Wickenburg would use scarce shot and shell to shoot and kill a vulture (bird). They were not good to eat and it would be a waste of ammunition in a country where supplies were scarce. Wickenburg gave various stories of how he came to name the mine.

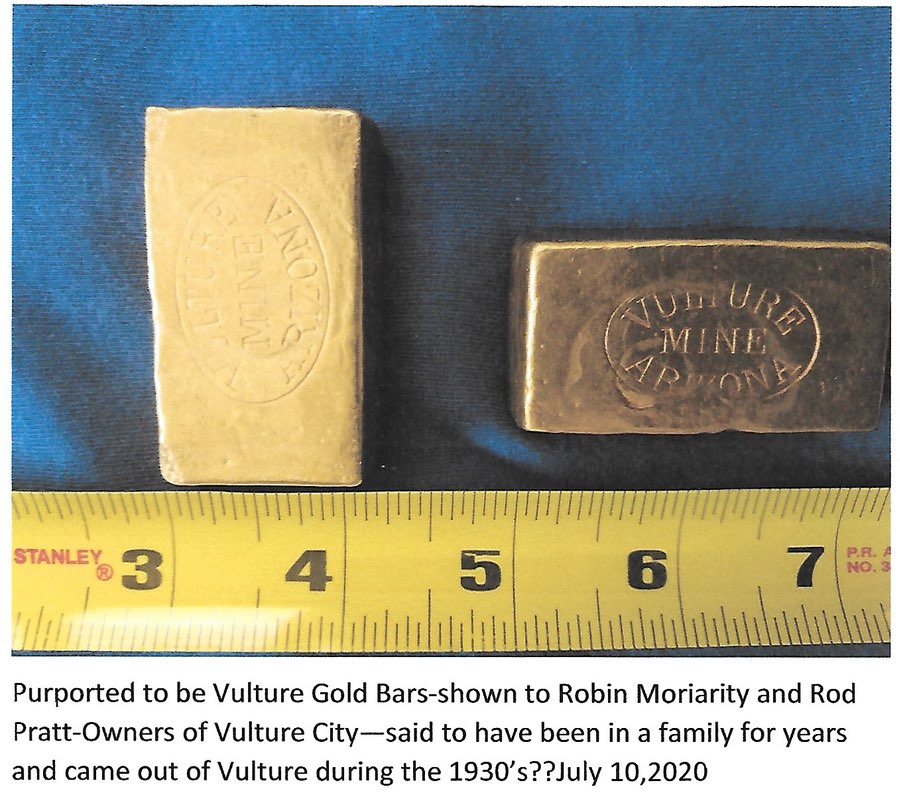

Gold estimates have run from a low of $6 million to as high as $200 million. Mining records would seem to indicate that the value in yesterday’s dollars was between $9 and $10 million dollars. A separate analysis by Don White is also in this ball park.

The current route that Grand Avenue takes as it goes from Phoenix to become state route 60 was originally called the Vulture Road as it was used to transport gold and passengers from the mine to Maricopa Wells and later to Phoenix. The stage line ran from Prescott to Phoenix and had stations at Wickenburg and the Vulture Mine (2nd site). Passengers could usually expect a two-day ride from Wickenburg to Phoenix, and roundtrip fare was $40.

Thomas Farish was/is known as the guru of Arizona historians and was the first state-appointed historian. Farish engaged in mining and took a lease when HAW Tabor had the property. During the last three months of the lease, Farish ran out of ore and began tearing down the old stone building on the property. The building had been constructed of rock from the mine so the stones went to the crusher.

There are tales that the stone in the assay office (still standing) is rich in gold. Waldo Twitchell, the mine assayer from 1911 to 1913, assayed that material and determined it held about $5/ton in gold. At that time gold was in the range of $20 an ounce.

Much talk surrounds the present pit, often called the “Glory Hole.” There is legend that “Sunday” miners and mules died in a cave-in and bodies were never found. Exact numbers differ as does the time span. Most frequently mentioned are that seven miners and twelve burros died in 1923. There is nothing to substantiate that legend. To the contrary, Arizona mining records show no fatalities for that year. Past and current operators who have been underground to virtually all areas have found no evidence, and as early as 1913 the rumor was active but mine workers then also believed it a tall tale.

Epilogue

Currently the Vulture property is divided between a group still attempting to extract some gold values and Vulture City Ghost Town which is an interesting tourist venue with exhibits and many buildings replicating what was once there.

Related: Vulture City, Arizona