Article By Gary Carter. Photos sourced by Western Mining History.

Numerous articles and books have described the techniques to extract valuable metals from waste rock. One of the best books on the subject is Drills and Mills by Will Meyerriecks. Meyerriecks describes the process of extracting metals from waste rock as “winning the metal”.

As methods and technologies became more advanced and innovative, it allowed mining companies to increase their profits by being more efficient and processing low grade ore they once stockpiled until the market price increased.

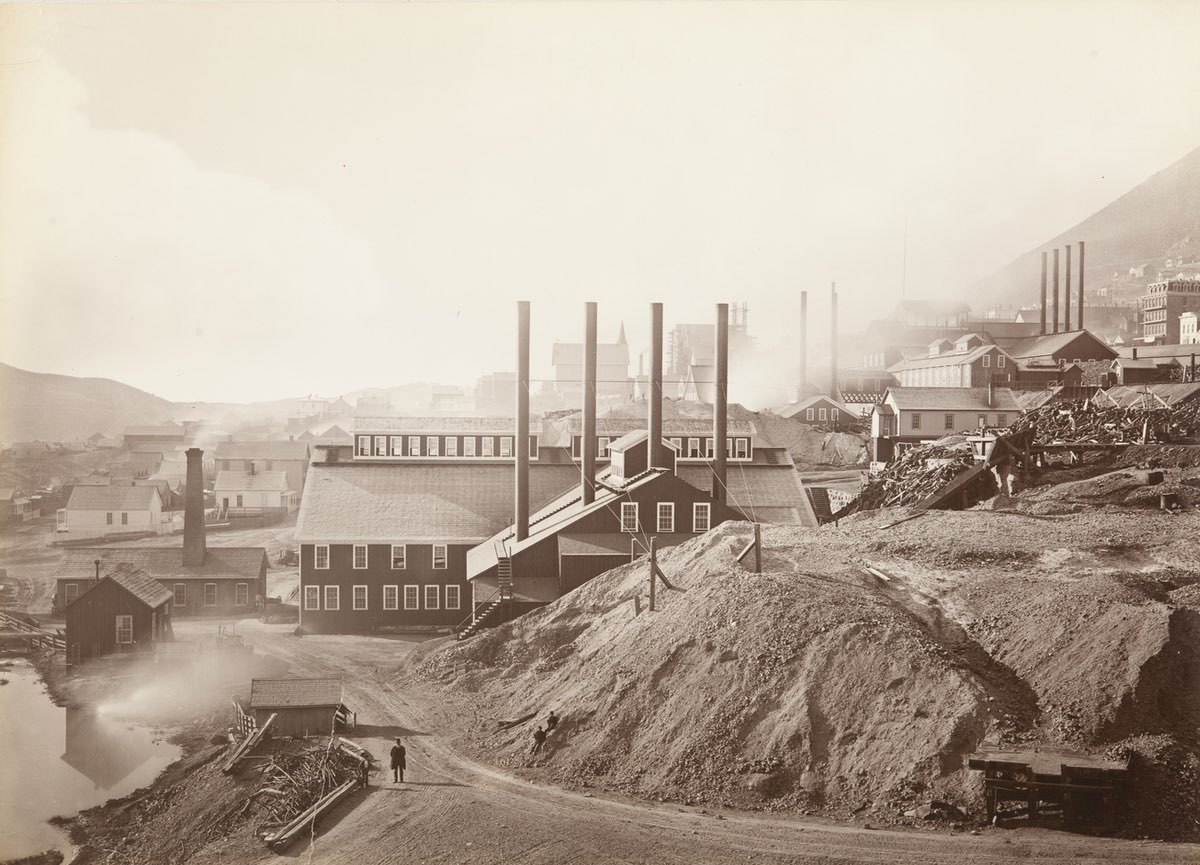

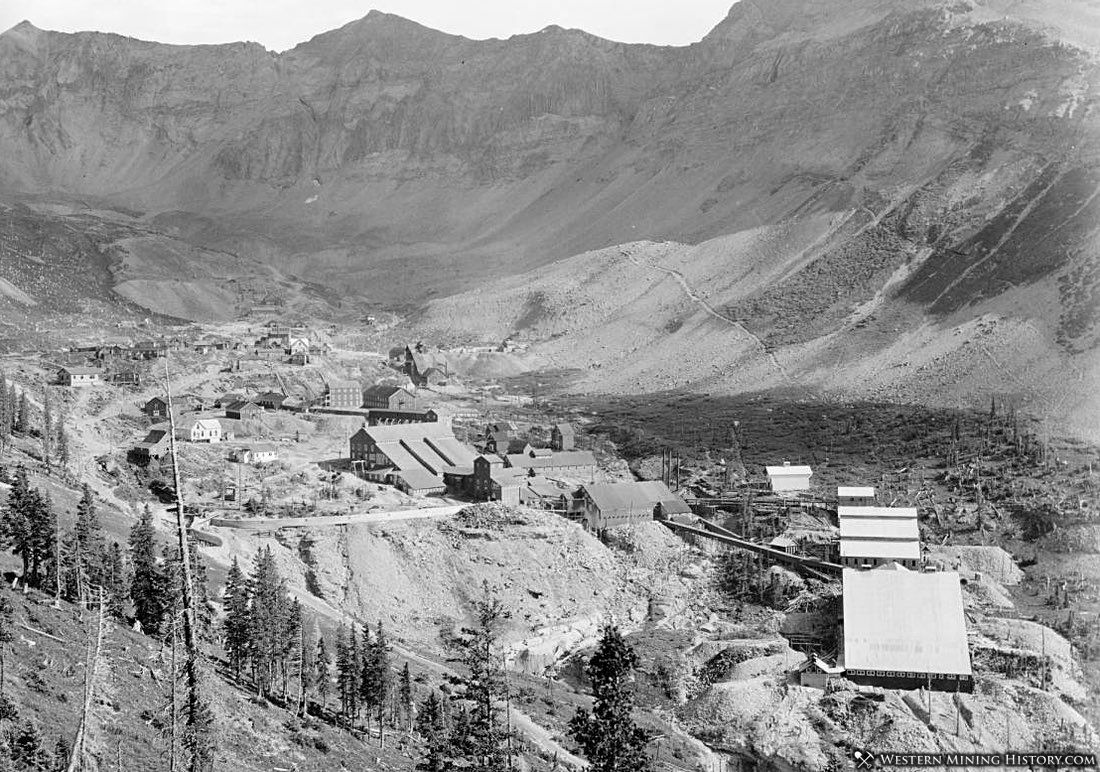

There are many different techniques to process the vast variety of ores that came out of western mines, and many mines often employed their own milling methods. This article will focus on the most common type of ore processing facility – the stamp mill.

An ore is any naturally occurring solid from which a metal or other commodity can be extracted for a profit. “For a profit” is the key phrase as many promising finds fail to have the quality or quantity of material to withstand the expense of mining and still return a profit.

Separating the valuable metal from the waste rock is not always an easy task. While gold, silver, and copper are sometimes found in their elemental state and not associated with other metals, that is infrequent except for placer gold. Zinc and lead are always chemically tied up with other elements.

It is the chore of the mill manager to decide what methods or techniques will be used to obtain the valuable commodity. Treating ore by milling is generally a two-step process, first the ore must be crushed, then the crushed ore must be treated to separate the valuable mineral content from the waste rock.

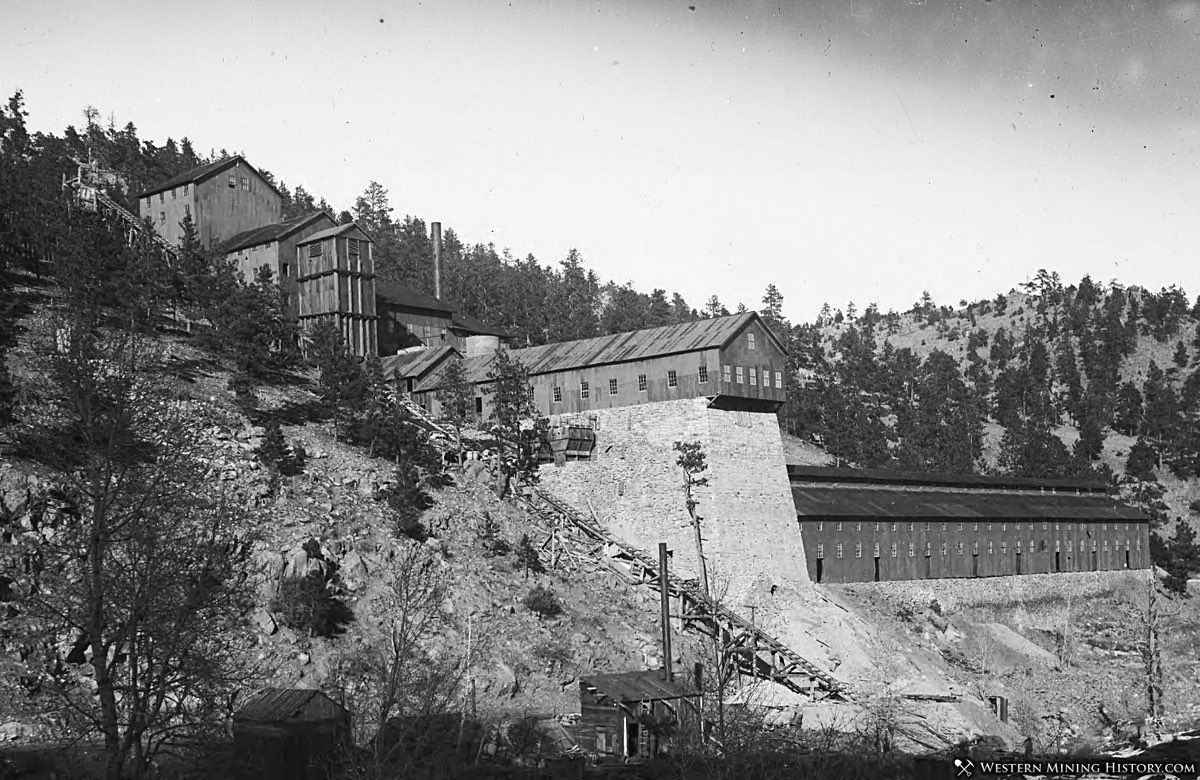

The earliest, and simplest method of crushing ore was the use of arrastras. When enough capital was available, stamp mills replaced arrastras at most mines.

The following sections take a look at various types of stamp mills, the most common milling facilities at mines of the frontier West.

Crushing the Ore

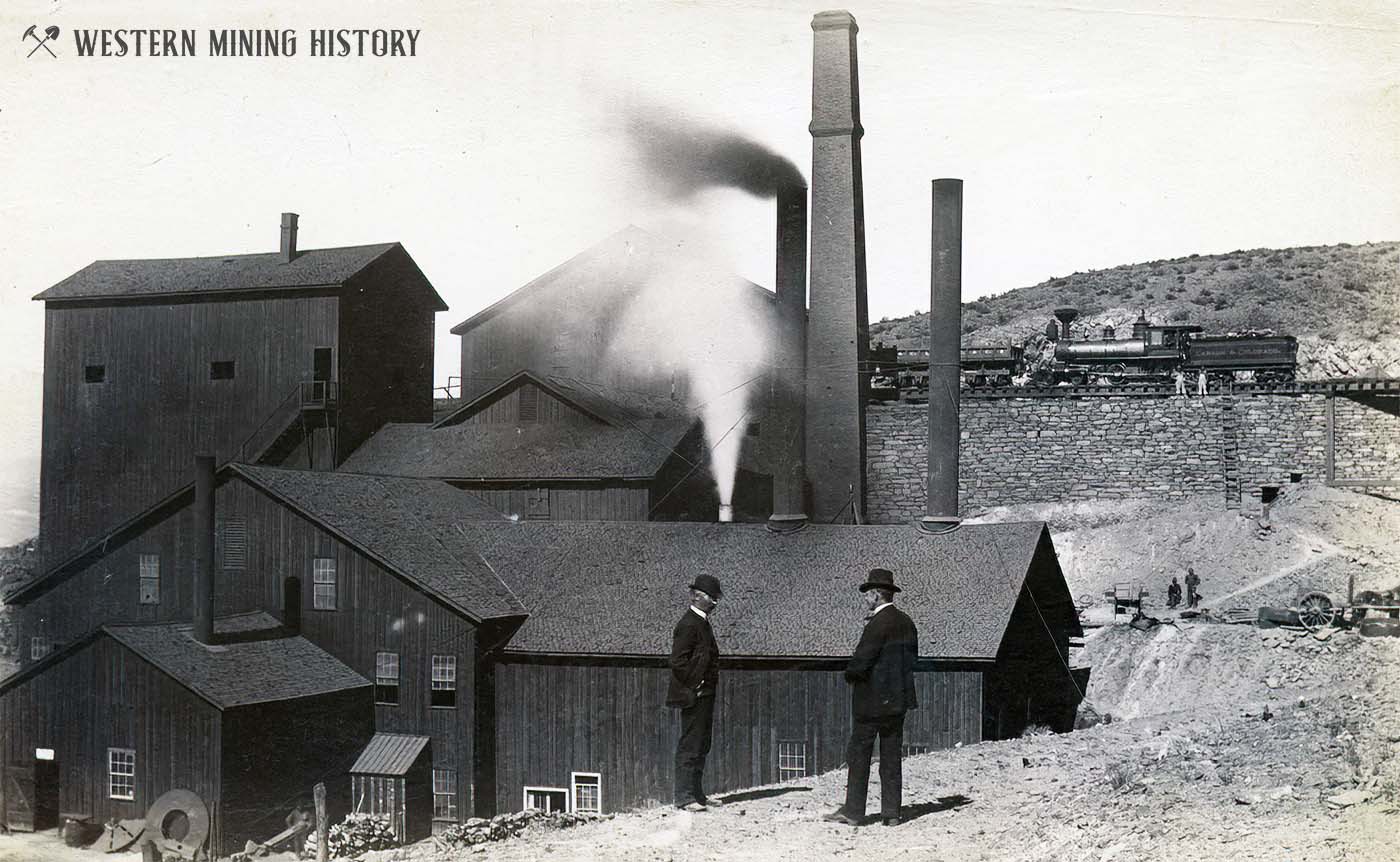

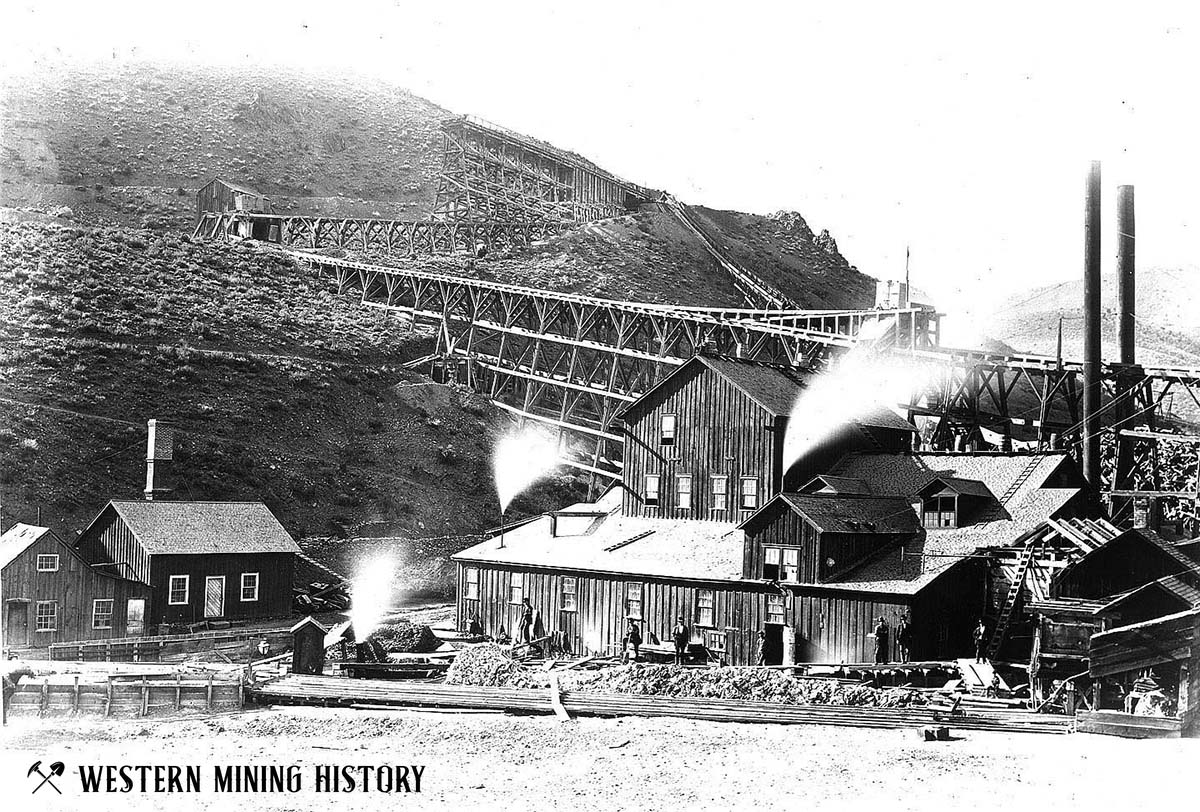

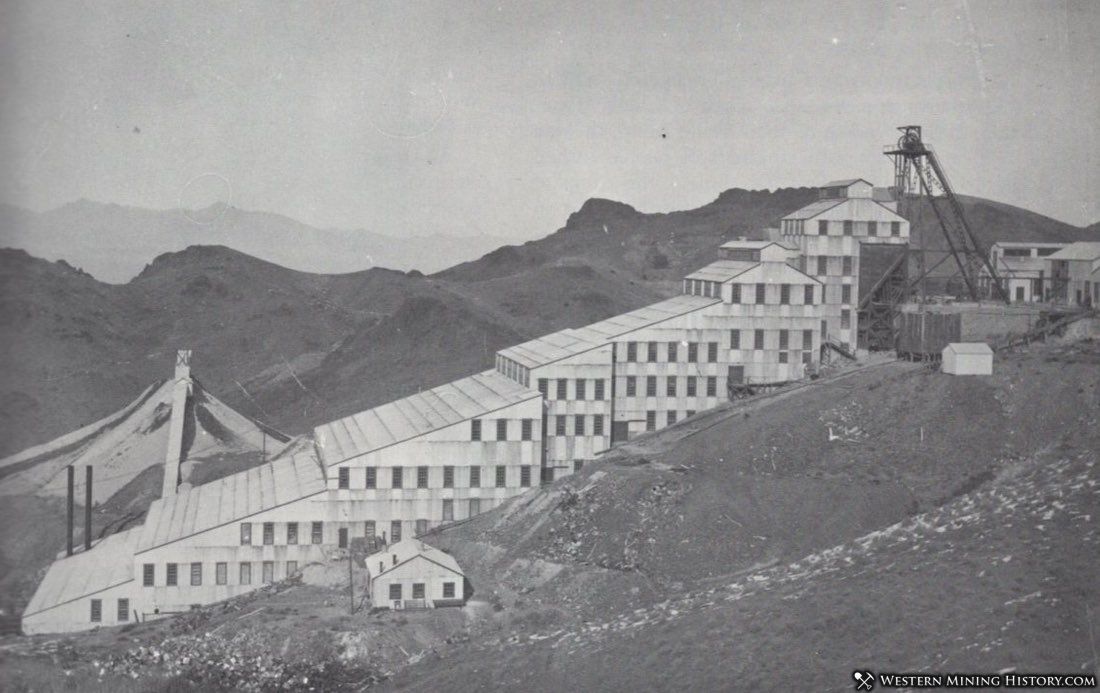

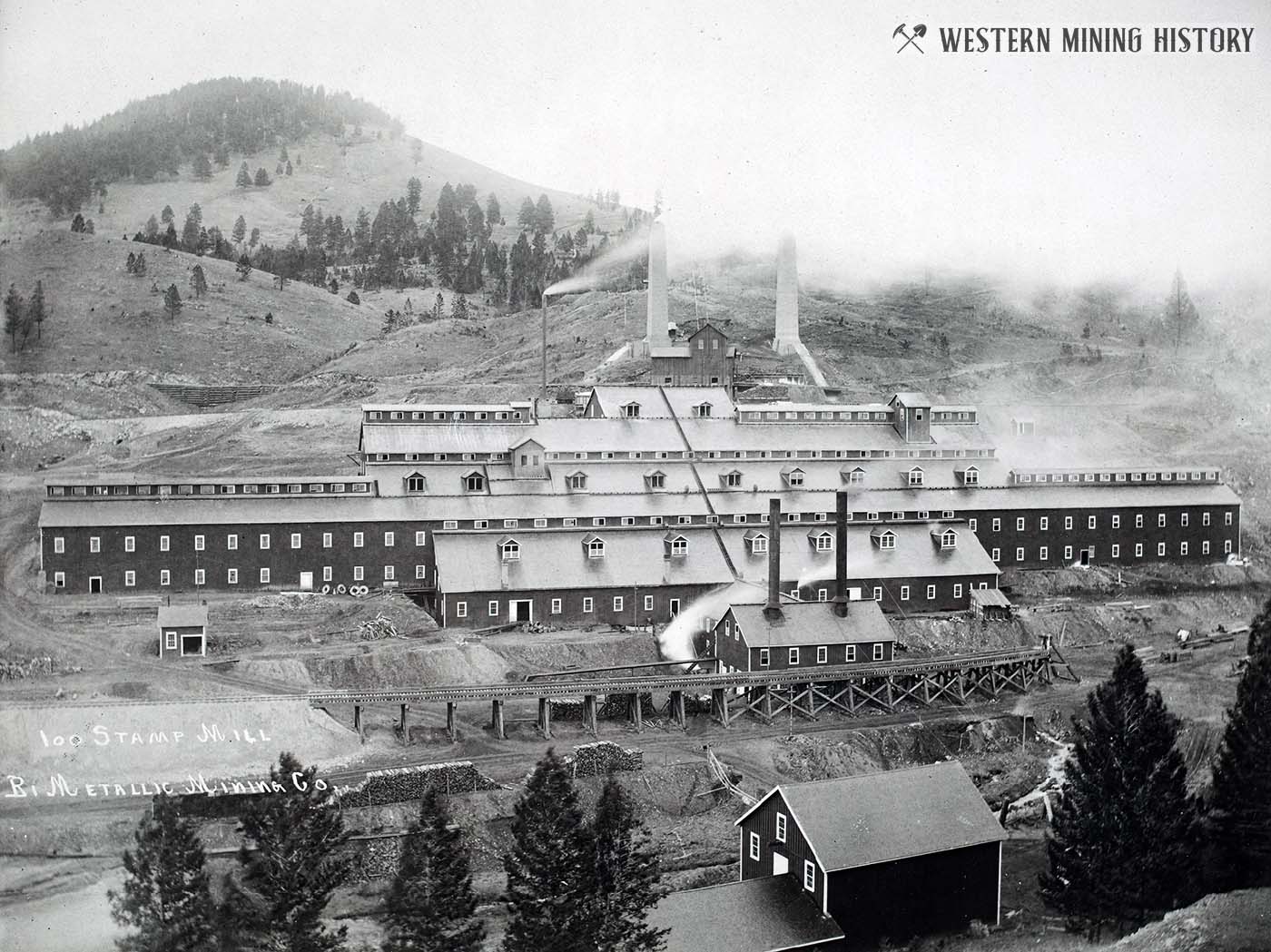

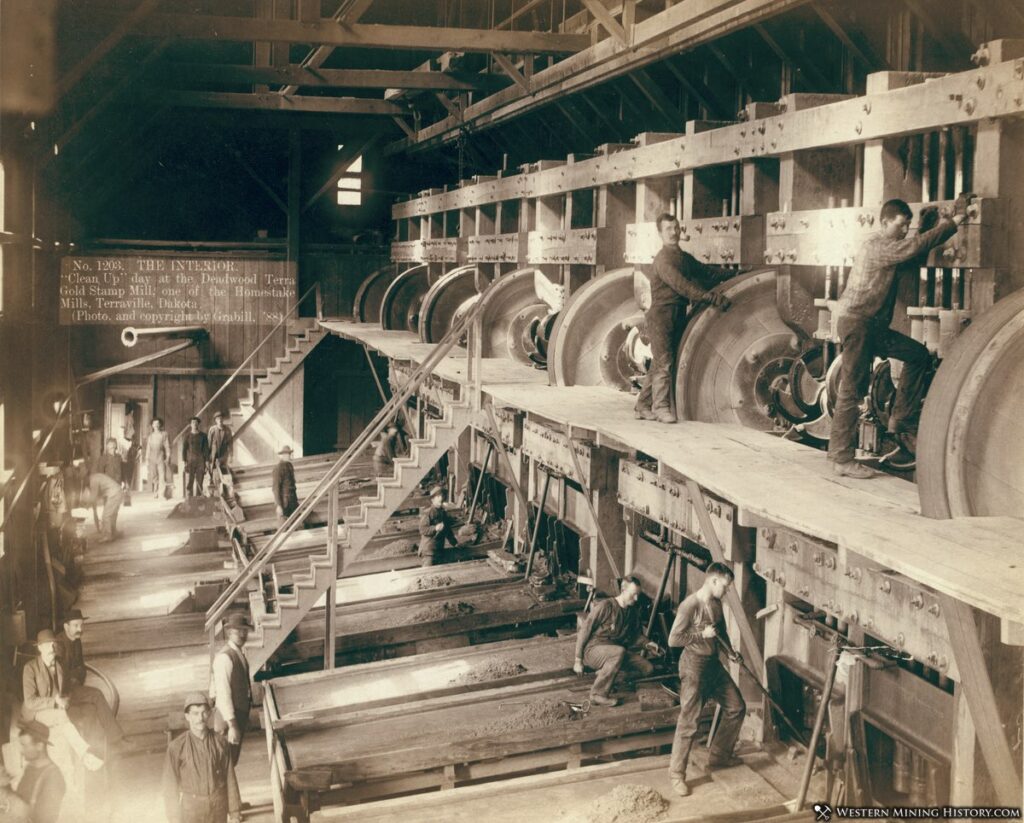

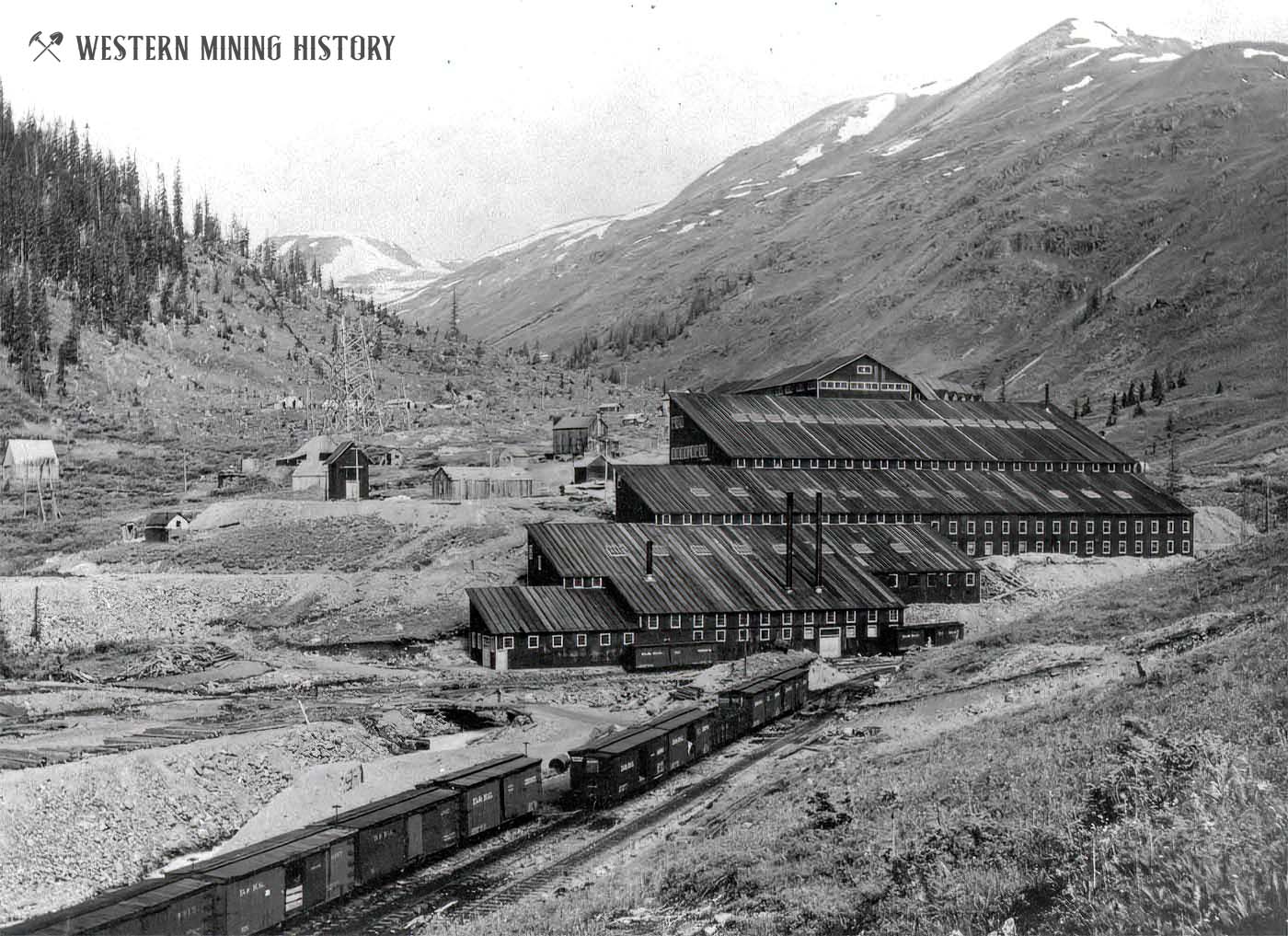

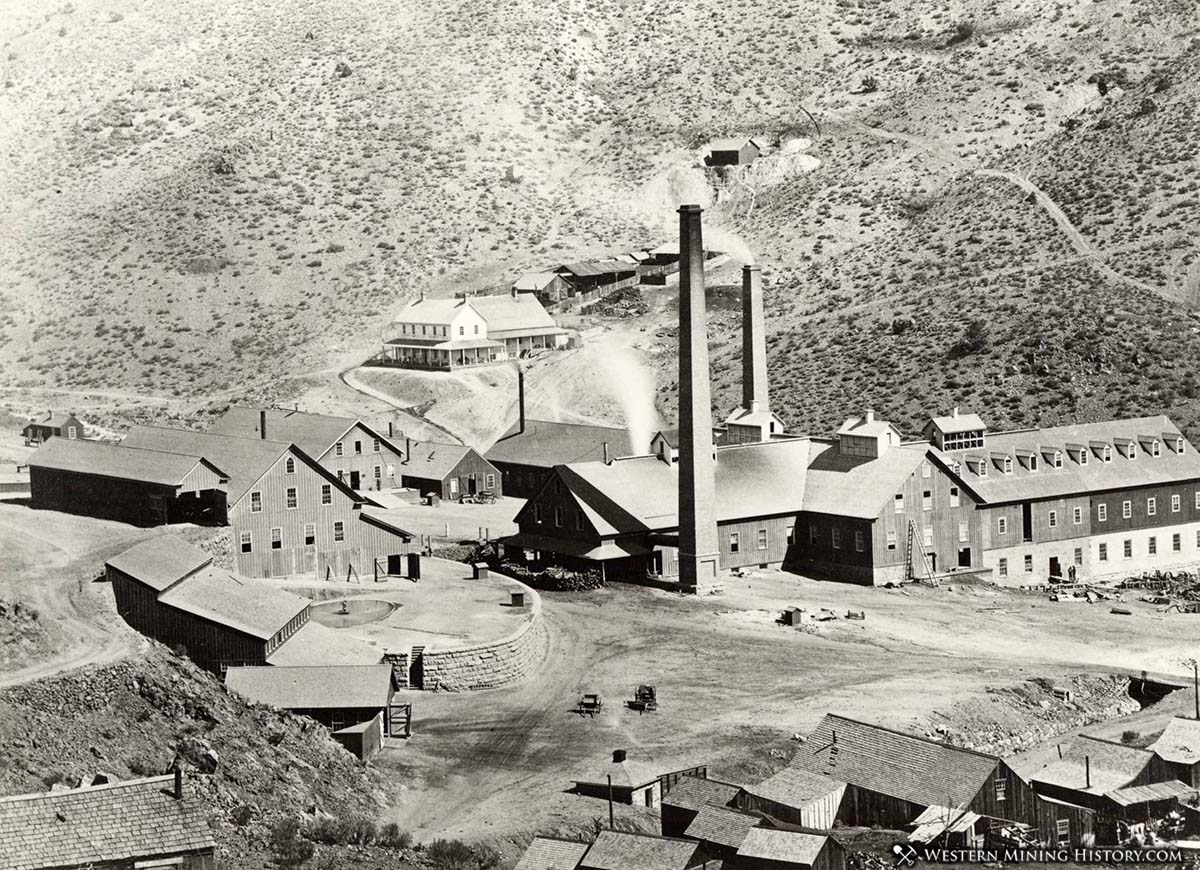

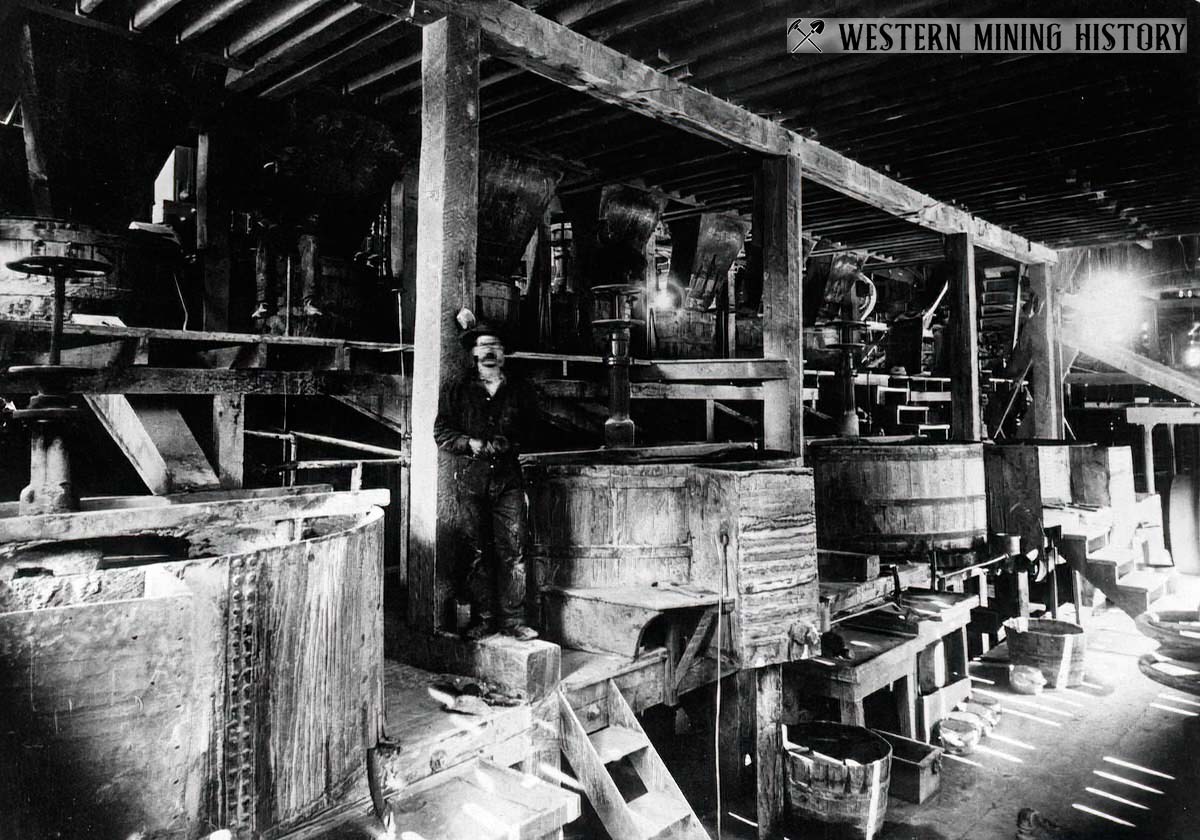

Mills consisted of machinery and materials set up to recover the valuable contents in ores. The mills were typically enclosed in buildings with the equipment arranged in levels, with the lower level last so gravity moved the product downward.

Between the 1860’s and 1880’s many processes were tried and abandoned before some were successful. Each ore deposit had its own peculiarities to contend with and methods effective on one mineral might prove to be a waste of time and money on others.

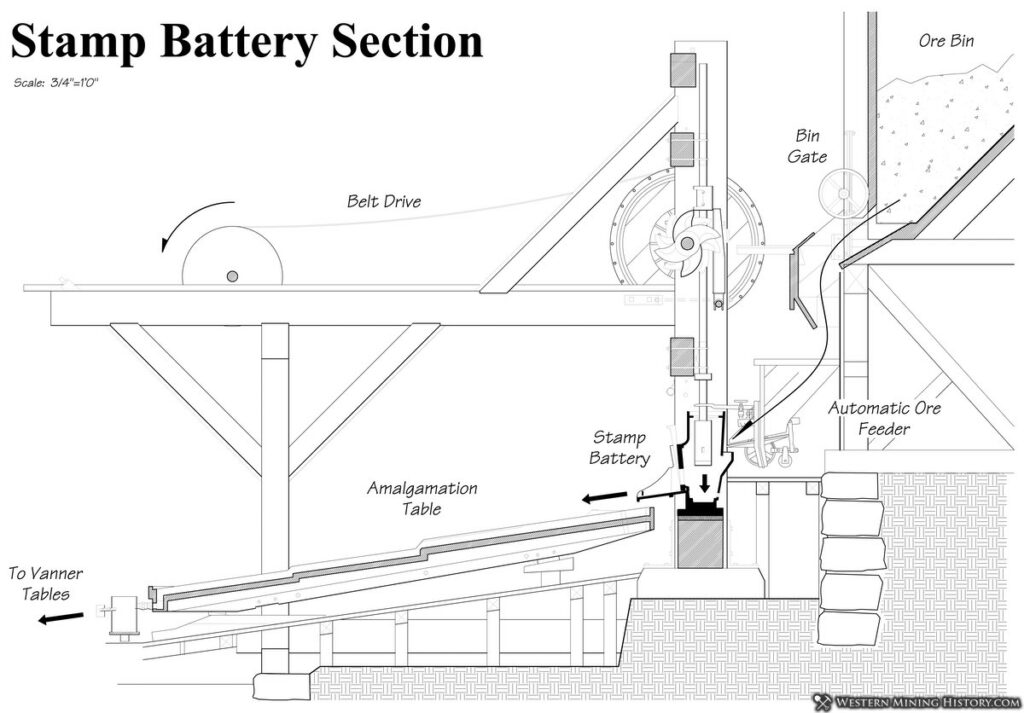

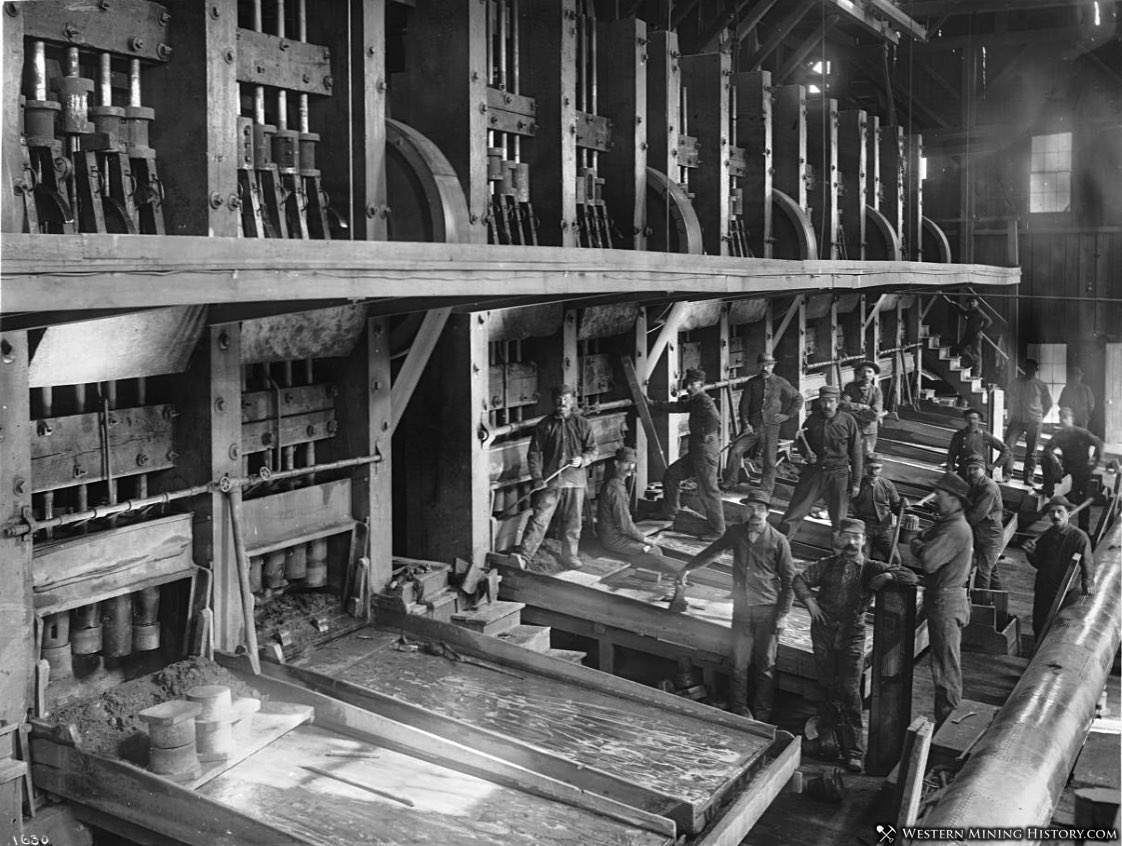

Whatever methods were used, water was the key liquid to carry the crushed “pulp” to the next stage of the milling process. Stamps were employed to do the crushing. Stamps were akin to using a mortar and pestle with the pestle being a long metal rod with a heavy iron “shoe” at the crushing end.

Blasted rock was fed from an ore bin and the stamps (usually in arrangements of five), raised and dropped by steam power, boomed away. At one time the Vulture Mill in Arizona ran 80 stamps and on a clear day the noise could be heard fifteen miles away!

For hard rock, stamps might weigh as much as 750 pounds, and water to the tune of 150-200 gallons an hour was fed into each stamp to produce a slick pulp.

It has been estimated that roughly ninety per cent of quartz bearing minerals were crushed by stamp mills. By 1875, California’s Gold Rush country had nearly 400 mills operating.

Stamps were the most common way to crush ore for many decades, but by the first few decades of the 1900s the ball mill started replacing stamps. By the 1930s, many stamp mills were retrofitted with ball crushers, replacing the stamps that were originally used.

While stamp mills throughout the west were similar in how they crushed the ore, the second stage – separation of the metals from the crushed ore – varied widely based on an array of factors.

Basic ores, sometimes called “free milling ore”, could be separated by relatively simple processes like amalgamation. Complex ore required more elaborate solutions, and as technology advanced, many new processes were introduced in western stamp mills.

The process of separating valuable metals from waste rock is known as concentration. The following section will take a look at some of the more common processes for creating ore concentrates.

Metal Recovery and Ore Concentration Techniques

Stamp mills would either ship the bullion product of free-milling ores, or it would ship a concentrate, the product of more complex ores, that would need further processing at a smelter.

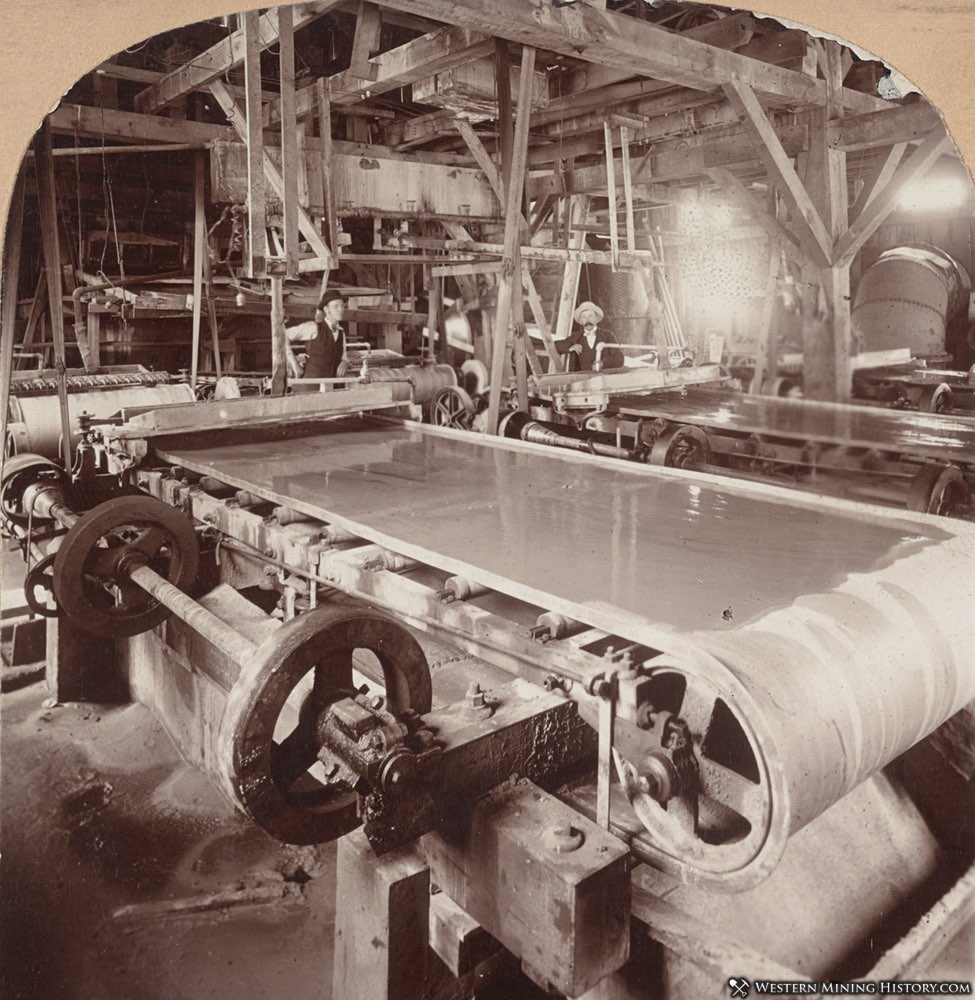

A variety of machines and techniques were developed to concentrate the crushed ore that came out of the stamps. Frue Vanners, Wilfley Tables, and Hendy’s Concentrators were just a few of the machines used at various times and locations to aid in the concentration of crushed ore.

For ores that required roasting, numerous furnace designs were developed during the latter half of the 1800s.

The following section will take a look at some of the more common metal recovery and concentration techniques used at western stamp mills.

Amalgamation

Liquid mercury has a unique characteristic of forming an alloy when it touches gold and silver. This process, known as amalgamation, was labor intensive, time consuming and dangerous as mercury, especially the vapor, is poisonous.

Ores were considered to be “free milling” if they could be treated straight forward by just crushing and amalgamation without the addition of a lot of steps. Amalgamation “plates” were long plates of mercury coated copper placed directly under the discharge of the stamp mills. The finely crushed rock, containing gold or silver, along with water, was slowly distributed over the plates and the mercury and metal ore would combine.

Cleanups or scraping off the plates to recover the amalgam was frequent and it was then strained to recover some of the mercury for reuse while the bulk of the “glob” was sent to the retort and heated to vaporize the vented mercury and then condensed to be used again. What remained in the retort (often a large crucible) was called “sponge gold” as the heating was not hot enough to melt the metal.

Small firebrick melting furnaces were then heated and the sponge gold (or silver) was melted (often a flux was added to speed the process), yielding a “dore” (a non-pure bar of gold and/or silver). The dore bars were then further refined at the mill, or sent to a smelter.

The patio process, the Washoe Process, The Sagebrush Process, Reese River Process and countless others were variations but crushing, amalgamating, perhaps adding chemicals for reaction and heating were the key steps.

For the silver ores of the Comstock both iron and salt were substances that would promote a chemical reaction with the silver. The Washoe Process was especially effective in liberating silver from sulfides. Large amalgamating “pans” replaced the plates.

In a 10 year period, the gigantic Consolidated Virginia Mill processed over 800,000 tons of gold and silver ore worth around sixty million dollars.

This description of the amalgamation process is very simplified as I have failed to mention many other steps and equipment (see the epilogue for a first person account of a milling setup).

A mill manager was as much a chef, keeping track of and improving the yield and efficiency, adding and removing reagents until the right combination was found. As milling became more scientific and sophisticated the mining company reduced costs and increased their profits.

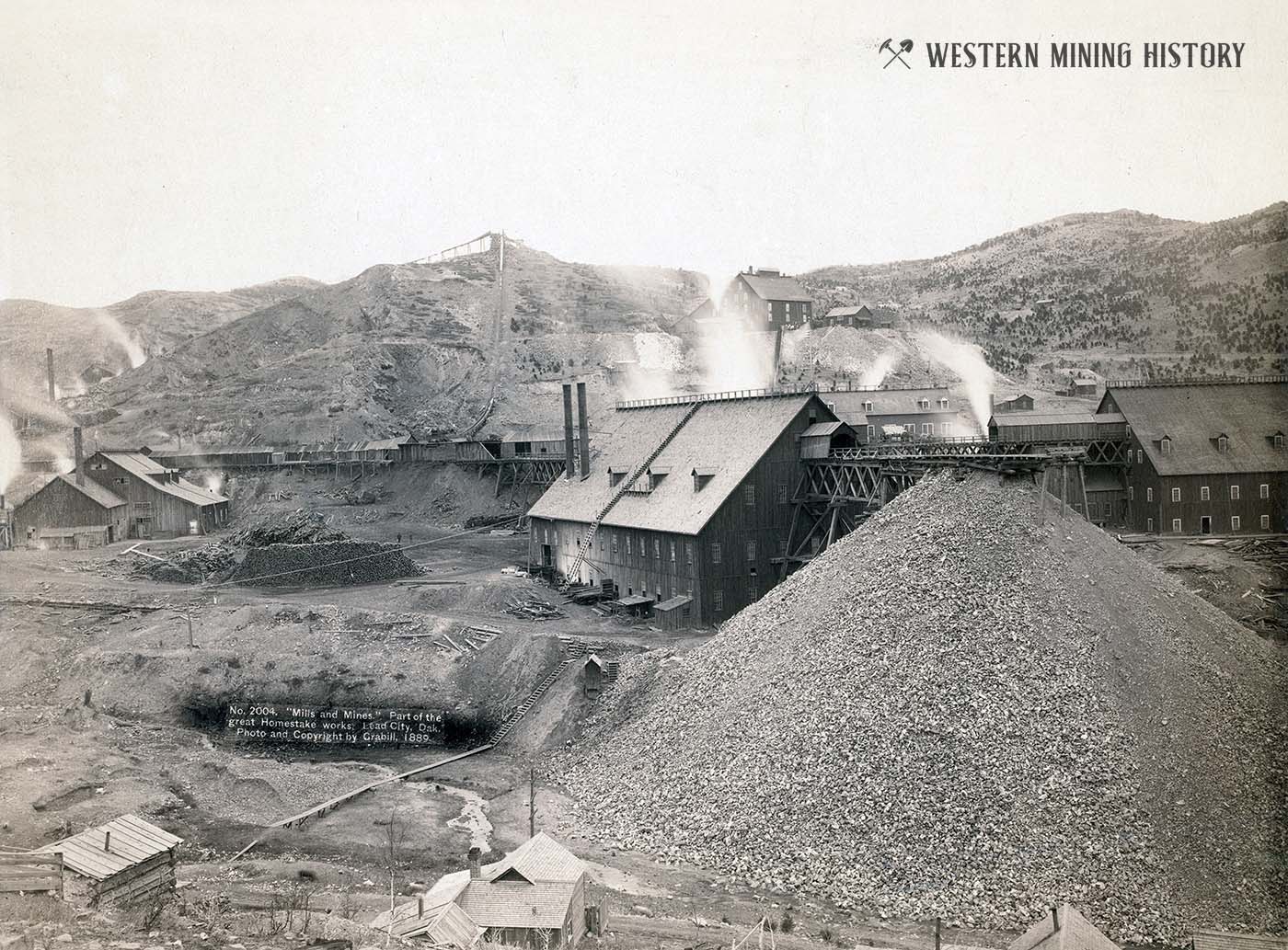

The Homestake Mine of South Dakota hung onto a form of amalgamation for its gold ore clear into the 1960’s when the method was replaced by cyanidation.

Chlorination

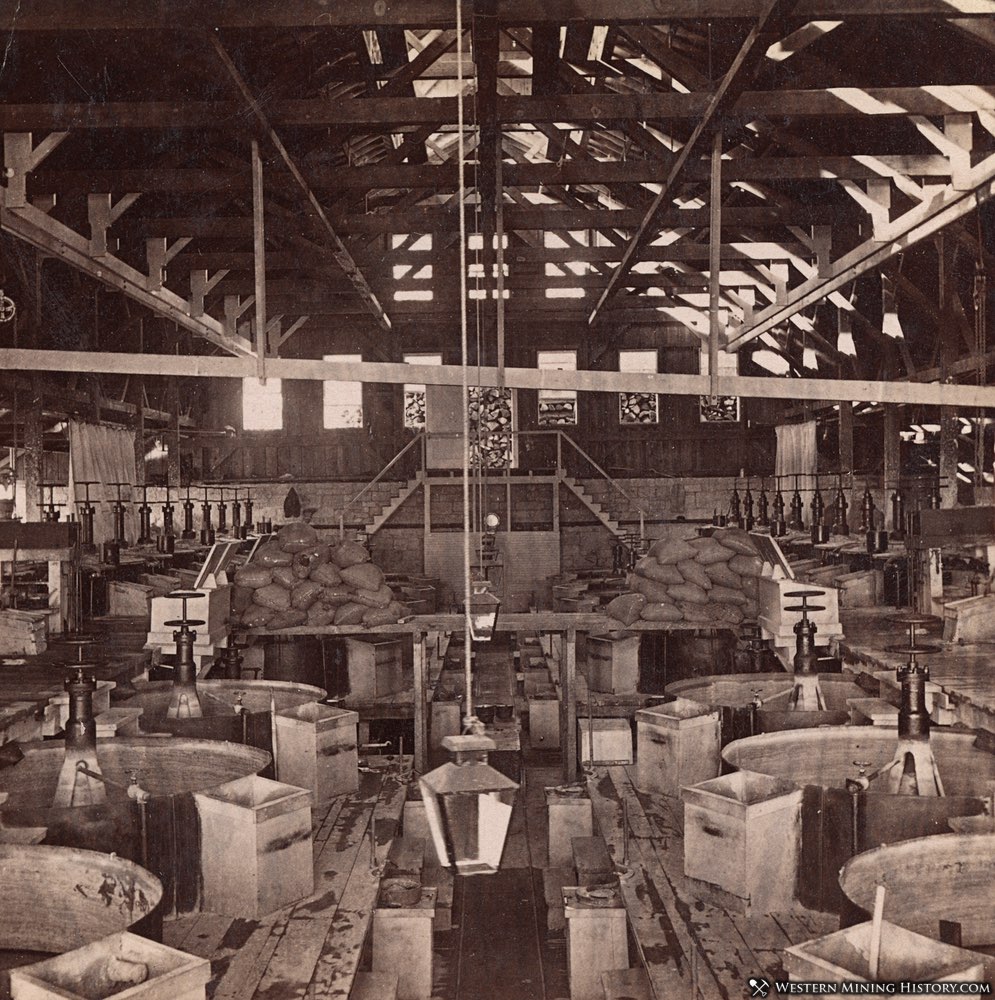

Using chlorine gas to extract gold began in the United States in the Mother Lode region. After roasting the ore chlorine compounds, acids, and attending chemicals were used in large vats with the ore to obtain a gold chloride solution that was then precipitated.

Chlorine gas was usually made at the site and depending on labor, fuel, efficiency and chemical costs, the chlorination process could be as effective as amalgamation.

A large chlorination mill was built at Wall Street, Colorado in 1903. The mill was built at great expense and was ultimately a failure. The Wall Street town profile page has a detailed description of how the chlorination process at that mill worked.

Due to the time involved and the dangers with the gas and chemicals, the process was eventually discontinued. The first mill seems to have been started in Cripple Creek in the late 1890’s.

Flotation and Cyanidation

As free milling ores gave way to more complex ones, especially sulfides, many milling techniques either did not work or were too costly or time consuming. Today, flotation froth (adding air bubbles) systems are in common use. Flotation methods improve recovery and decrease time and expense.

It had been long known that gold is soluble in a potassium cyanide solution, however it was not until the late 1880’s when an organized patented process of using cyanide to dissolve gold began to be used. Once it proved successful the process spread quickly throughout the western mills.

Basically, a cyanide solution is sprayed or is introduced into large vats or outdoor “heaps” (as in heap leach piles) of finely crushed ores that it can dissolve. Chemical combinations are then set up to release the gold from the pregnant cyanide solution.

Today flotation and cyanidation are commonly used in ore mills.

The Great Mills

Some mills were as famous as the mines that supplied them. I will leave it to the interested reader or researcher to investigate this list of some of the more famous mills:

The Consolidated Virginia Mill, Standard Mill at Bodie, Anaconda and Dexter mills in Montana, Mercur (perhaps first to use the cyanide process), Silver King, and Ontario mills in Utah, The Stuart Mill in Montana, The Golden Star and Homestake mills in South Dakota, the Old Hundred Mill in Colorado, the Carissa Mill, Wyoming.

Idaho had its Silver Valley with mills working the lead and silver deposits. In California, the Benton, Allison, Sierra Buttes, Jamison, Eureka, and Johnstown are just a few of the many interesting mill stories in the old California Mother Lode Country.

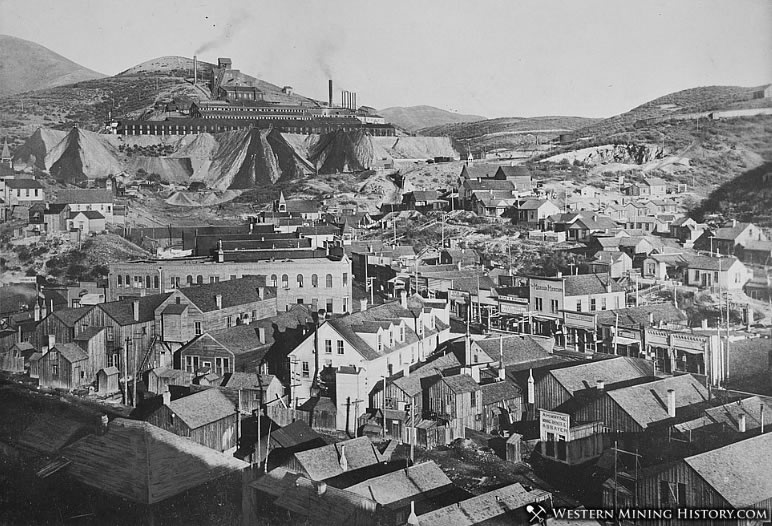

There are also mills that were famous for being spectacular failures. One of the most stunning examples was the Gould & Curry Mill of Virginia City, Nevada.

Built in 1863 at a cost of over $900,000, then rebuilt just a couple years later at an additional cost of $560,000, this mill was a monument to the excesses of the Comstock at that time. The extravagance of the mill was detailed by Eliot Lord in his 1883 book Comstock Mining and Miners: “The extraordinary mill of the Gould & Curry Company was, however, the most conspicuous monument of inexperience and extravagance ever erected in a mining district.”

The Gould & Curry mill was sold and by 1873 completely disassembled and removed. The Omega Mill was built in its place.

Related: Arrastras Illustrated in These Historical Photos

Epilogue

It is almost impossible to describe, let alone do justice to, the variety of processes that have been used to mill ore. The importance of mills cannot be understated since no money was made until the minerals were stripped of their metal values by the mill.

A good metallurgist or mill man was literally worth their weight in bullion. Much of what they did was innovative, experimental, and trial and error as to how much or how many chemicals to add, how long to grind, or amalgamate.

We have not discussed the ways and fine points of smelting, roasting, and each had a slightly different method, furnace, and flux to gain what the mill manager felt was the biggest return for the smallest cost. At one time, in its heyday the great lead – silver areas of Leadville, Colorado had sixteen smelters with over thirty furnaces.

Multiple pieces of equipment were in the mills to facilitate extraction and the following account provides one with a verbatim account from Waldo Twitchell the assayer at the Vulture Mine in Arizona, of their mill operation in 1912:

“The new mill was erected in 1910, at a cost of about $80,000. The capacity is about 100 tons of ore a day. The quartz mill at the Vulture is a modern twenty stamp mill, each stamp weighing over a ton. At this time, the stamps are the heaviest in use in the country. The ore is taken from the mine and crushed to a suitable size in an Allis-Chalmers gyratory crusher, carried to the storage bin in an ore car. Eventually, a 4 ton ore car is hauled up a tramway and ore stored in a second bin at the mill. This bin feeds direct to the stamps.”

“The ore is crushed in a solution of cyanide water with amalgamation taking place in the mortars. Plates(amalgamation) are not used. The pulp is passed through a 30 mesh screen and then over a Dorr Classifier( for separation). The classifier slimes are sent to a Dorr Thickener #1. Other fines (lead minerals) are sent to regrinding pans and then to Wilfley Tables (use specific gravity to sort metals) where the lead concentrates are taken off, dried and shipped to a smelter at El Paso.”

“The Wilfley tails are passed over a Deister slimer, concentrates removed (again). There are 4 Dorr Continuous Thickeners used. The cyanide solution is precipitated by means of zinc dust discharged from an endless belt into a cone. The cyanide and zinc combine precipitating the “dirty gold”). The precipitate is collected in a Merrill Filter Press with triangular leaves then dried, fluxed, melted and refined at the mine.”

There is not a lot about the old mills and processes easily accessible, in print but I would suggest “Drills and Mills” by Will Meyerriecks, and the old standby of Otis E. Young, Jr., “Western Mining”, for more specific information on the various mill processes.