Ajo History

Spaniards and Mexicans were working the copper deposits at Ajo as early as 1750, though these early operations were intermittent and of limited scale. Ajo is believed to be the second copper district worked by Americans in the Southwest, after Santa Rita, New Mexico.

American involvement in the district was described in the 1946 USGS publication The Ajo Mining District Arizona:

The Ajo mine was located in November 1854 by a party of Americans from California. The organization was known as the Arizona Copper Mining and Trading Co. Maj. Robert Allen, U. S. A. , deputy quartermaster-general of the Department of the Pacific, was the president of the corporation, and J. Downer Wilson, of San Francisco, was secretary and treasurer.

At that date the present boundary line between Sonora, Mexico, and the territory of the United States had not been determined, and its position was not ascertained until the following year, 1855.

As soon as the region began to be occupied by citizens of the United States and work commenced on the Ajo mines, these mines were claimed by several wealthy residents of Sonora as being within Mexican territory. In the month of March, 1855, a Mexican company of cavalry was sent from the district of Altar and from Ures, the capital of Sonora at that time, to dispossess the Americans, to capture them, and take them to Ures as prisoners. But the miners refused to go and defended their position. With only 9 men against 110 dragoons and vaqueros, the mine was successfully held and the Mexicans were dispersed.

For 6 months after this nothing was done beyond mere prospecting, but in the fall of the year 1855 the boundary line had been run, and it was found that the Ajo mining camp was at least 40 miles inside of the boundary on the United States side. Edward E. Dunbar, one of the pioneer residents of San Francisco, was then made the superintendent of the property, and work was resumed in a formal manner. The mining locations, of which there were 17 made in that year, all had some work done on them.

In the meantime 10 tons of selected ore had been taken from shaft No. 1. This ore consisted of red oxide of copper. It was shipped to Swansea and was sold for a little less than $400 per ton. There were several hundred tons of sulphurets of copper extracted from the different workings. The principal portions were in a limestone formation, but the richest ores were all found near where the first work was done and were in porphyry.

The company attempted to transport the ore to San Francisco and thence around Cape Horn to Europe, but the costs were so great that their plan of transportation had to be abandoned. For the first year, on every pound of ore transported from the mine by way of Yuma to San Francisco the freight alone amounted to 9 cents. A reverberatory furnace was built at a cost of over $30,000, and not as much as 100 pounds of copper was ever produced in it.

Finally, after several years of great expenditure, the company ceased operations. The property was left in charge of a keeper whose claim for services amounted to $5,000, and the property was sold at sheriff's sale.

In the decades that followed, repeated attempts were made to profitably mine the low-grade ores of the Ajo mines, but none succeeded. Each effort was ultimately derailed by a combination of challenges, including a lack of water, inadequate transportation infrastructure, and the difficulty of processing the ore.

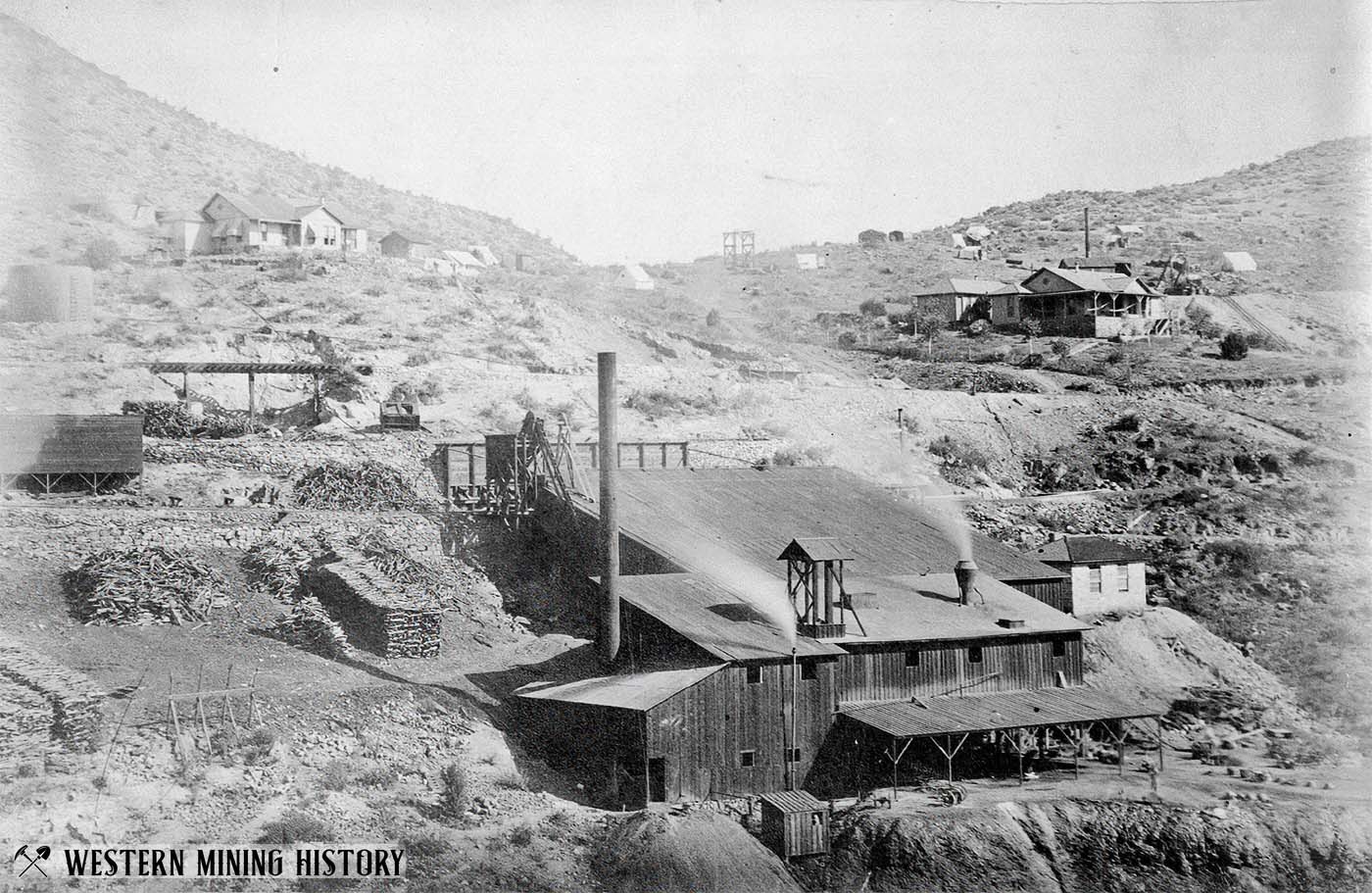

Interest in the deposits never waned however, and by the late 1880s more concerted efforts were being made to get the mines going, including the construction of a 10-stamp mill by the St. Louis Copper Co. In 1900, a post office was established at the community of Ajo.

These renewed mining efforts also ended in failure, as the stamp mill technology of the time proved inadequate for profitably recovering copper from the Ajo ores. Ownership of the claims changed hands repeatedly, as investors and experienced mining professionals persisted in their attempts to solve the challenging problem of economically extracting copper from the low-grade deposits.

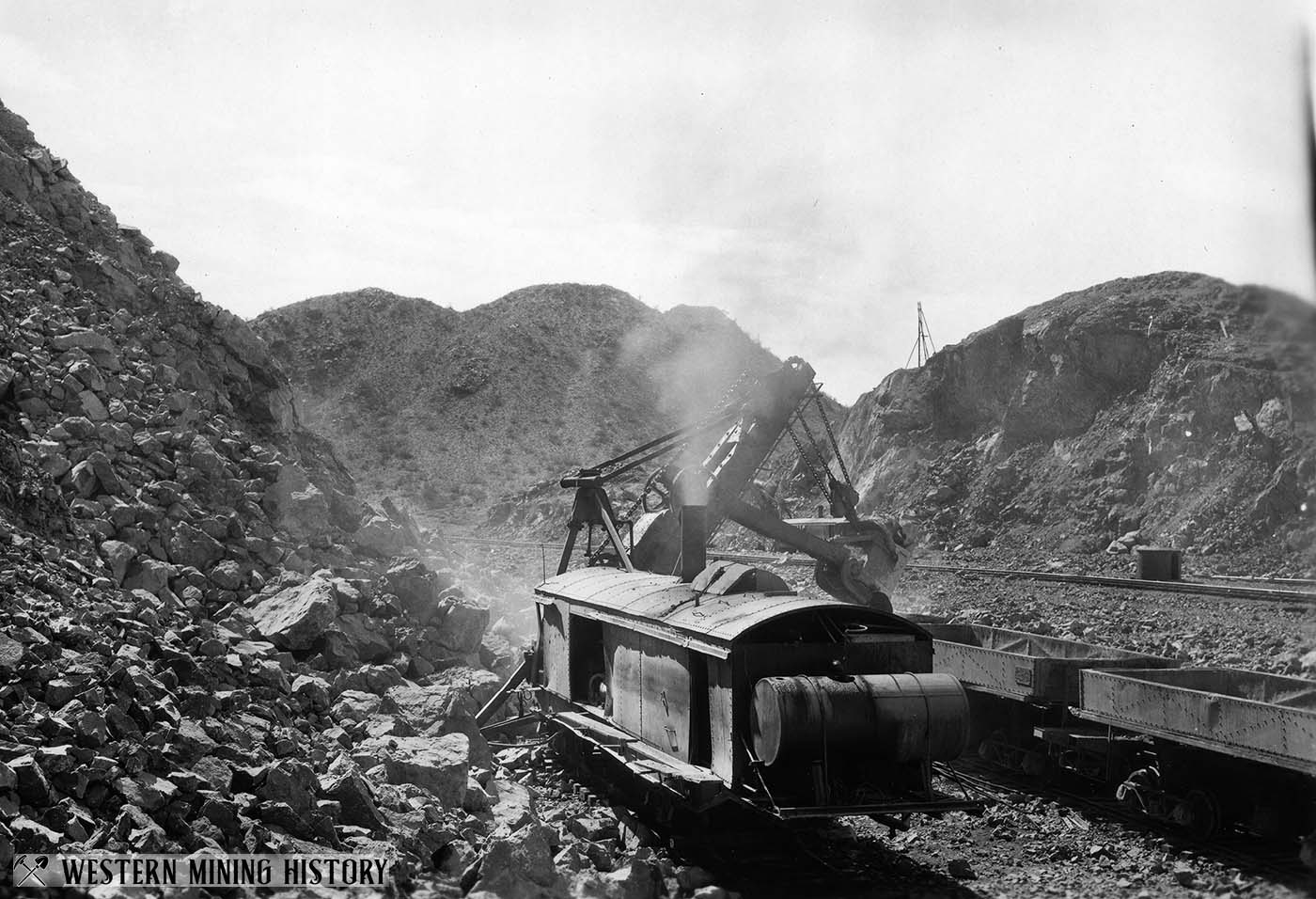

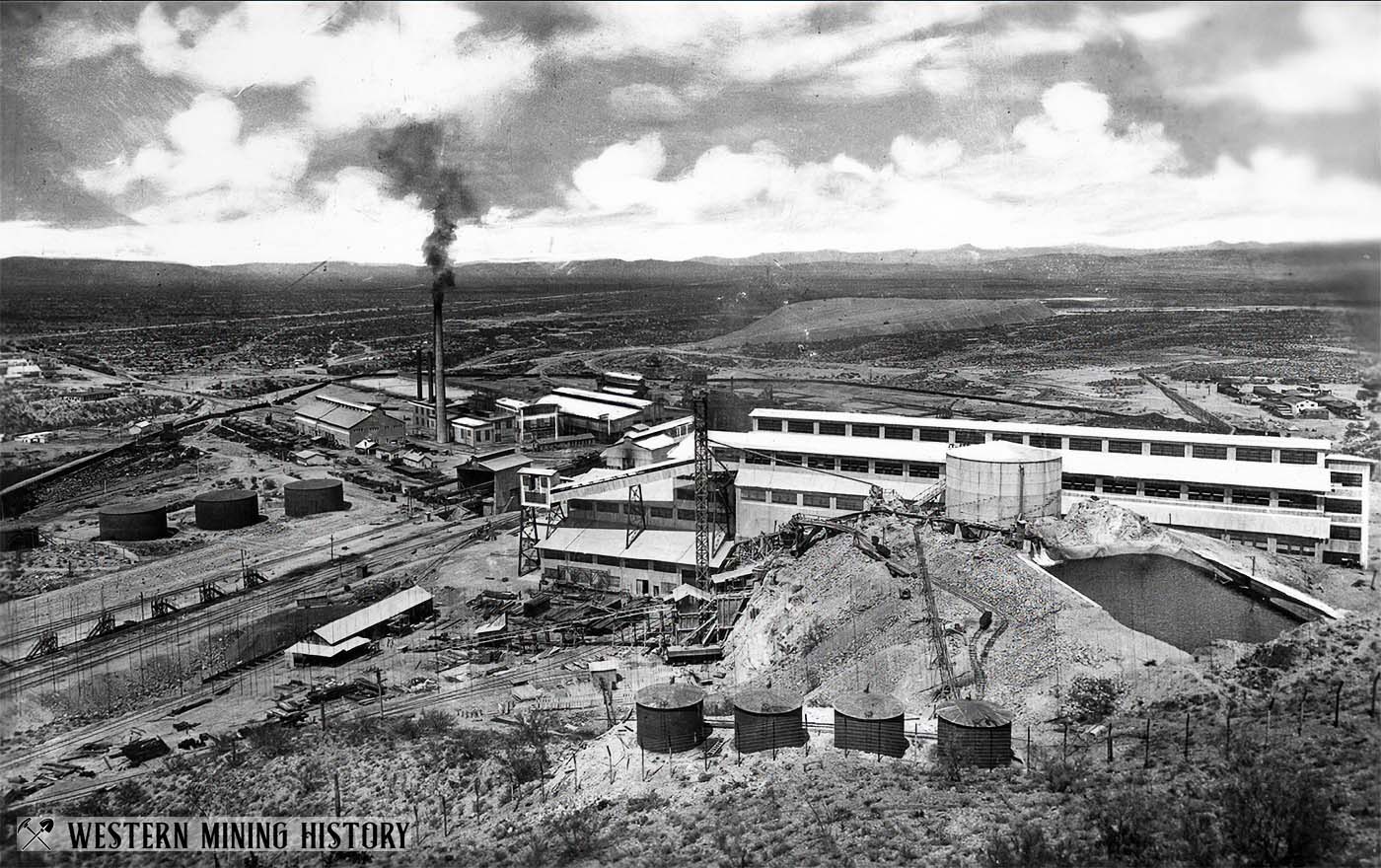

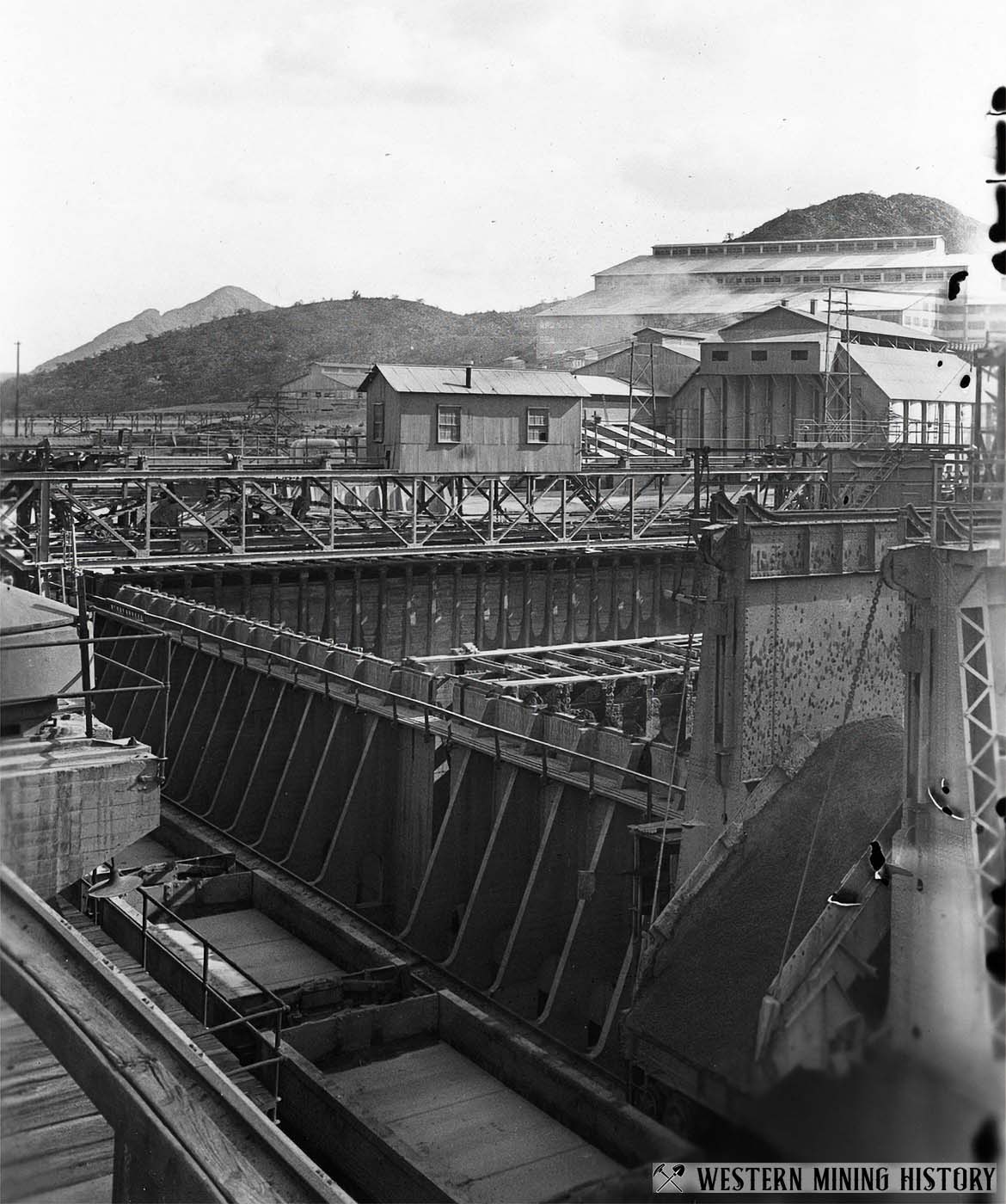

In 1912, the New Cornelia Copper Company conducted successful experiments in leaching copper ore, marking a turning point for mining operations at Ajo. Building on this breakthrough, railroad lines were surveyed, and a major initiative was launched to locate and develop reliable water sources to support the mine and leaching plant.

By 1916, the railroad to Ajo was completed, and in May 1917, a 5,000-ton leaching plant was brought online. The new operation proved immediately successful—by the end of 1917, the New Cornelia mine had produced over 19 million pounds of copper.

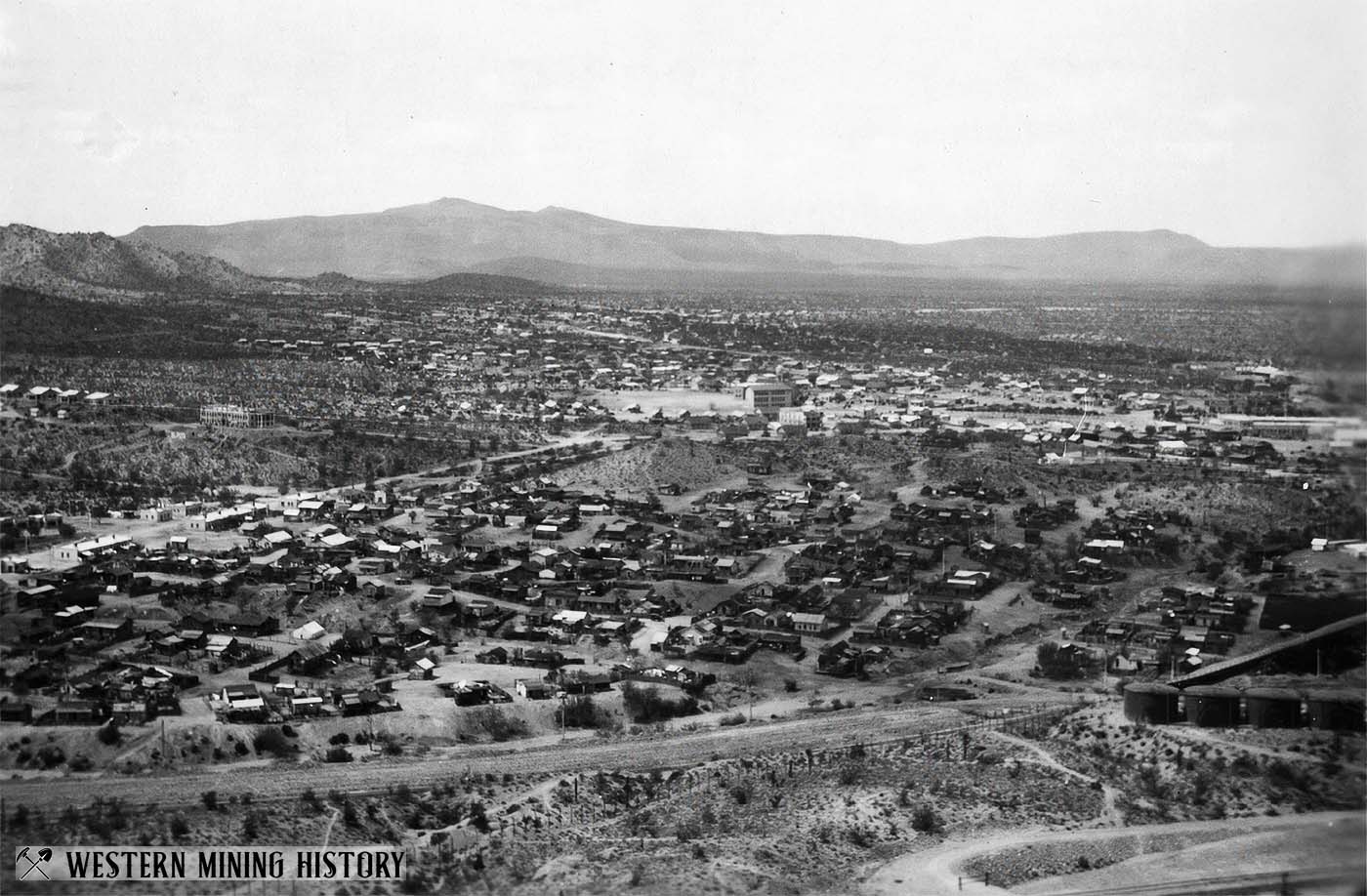

The New Cornelia mine was planned as a large-scale open-pit operation, but the original town of Ajo sat directly atop the ore deposit. As a result, a new company town was built about a mile to the north. Featuring artistically designed streets and attractive, well-built concrete homes, it was a model town complete with a central plaza, stores, hotels, a hospital, paved roads, a reliable water supply, a sewage system, and a bank.

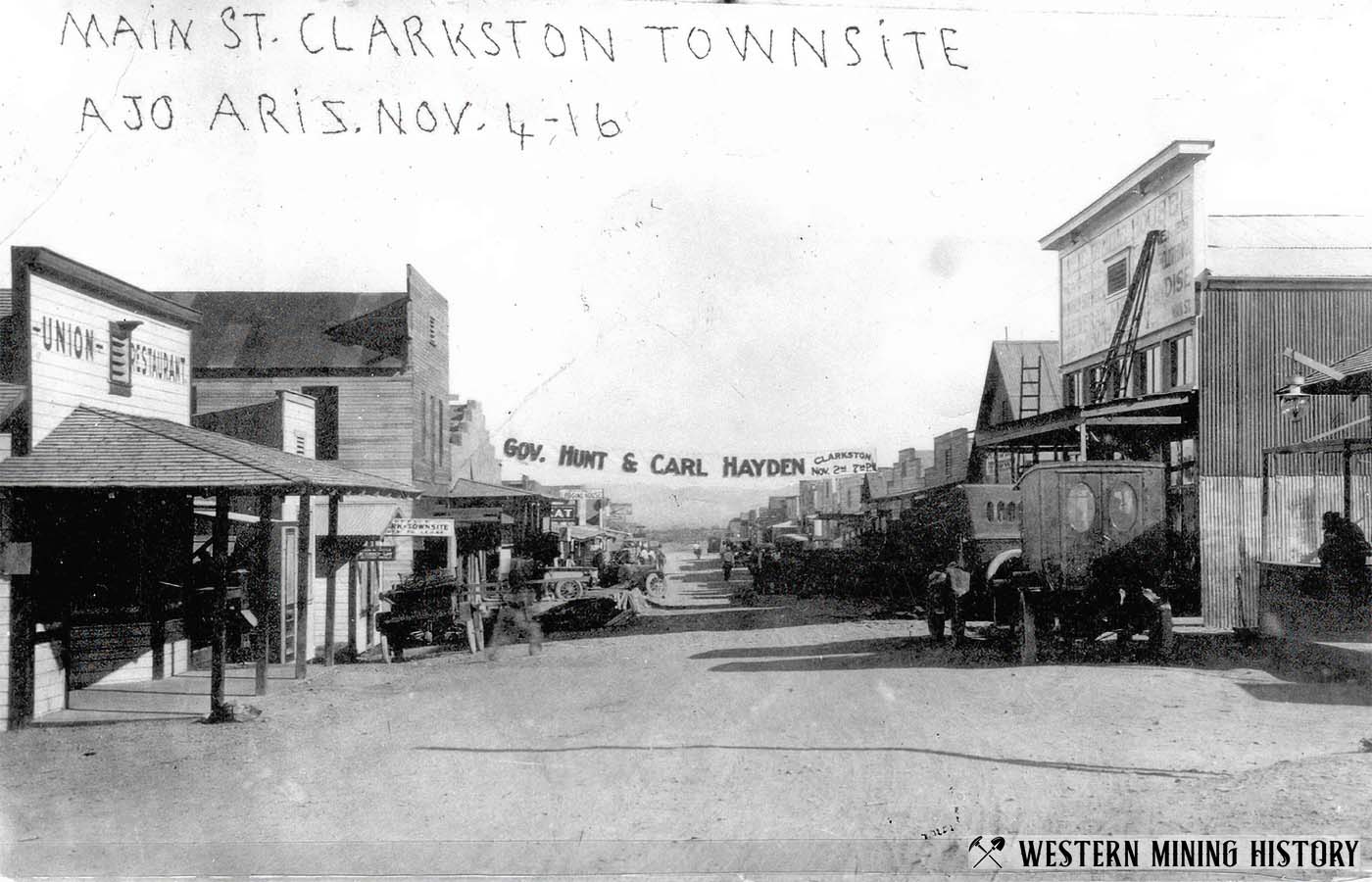

Not everyone wanted to live in a company town however, so the settlement of Clarkstown was established just east of the leaching plant. During 1916 and 1917, Clarkston was the largest settlement in the area with between 800 and 1,200 residents. Once the company town was completed however, Ajo became the principal settlement and Clarkston faded.

In 1929 the New Cornelia Copper Co. was consolidated with the Calumet and Arizona Copper Co., and the new company was merged with the Phelps Dodge Corporation in 1931. The New Cornelia mine was in production almost continuously until finally closing in 1985. The town of Ajo peaked around 1960 with just over 7,000 residents.

The loss of 1,000 mining jobs dealt a significant blow to the community, but like the former copper towns of Jerome and Bisbee, Ajo has successfully reinvented itself as a tourist destination. Today, it attracts visitors and retirees alike with its unique charm, rich history, and scenic desert surroundings.

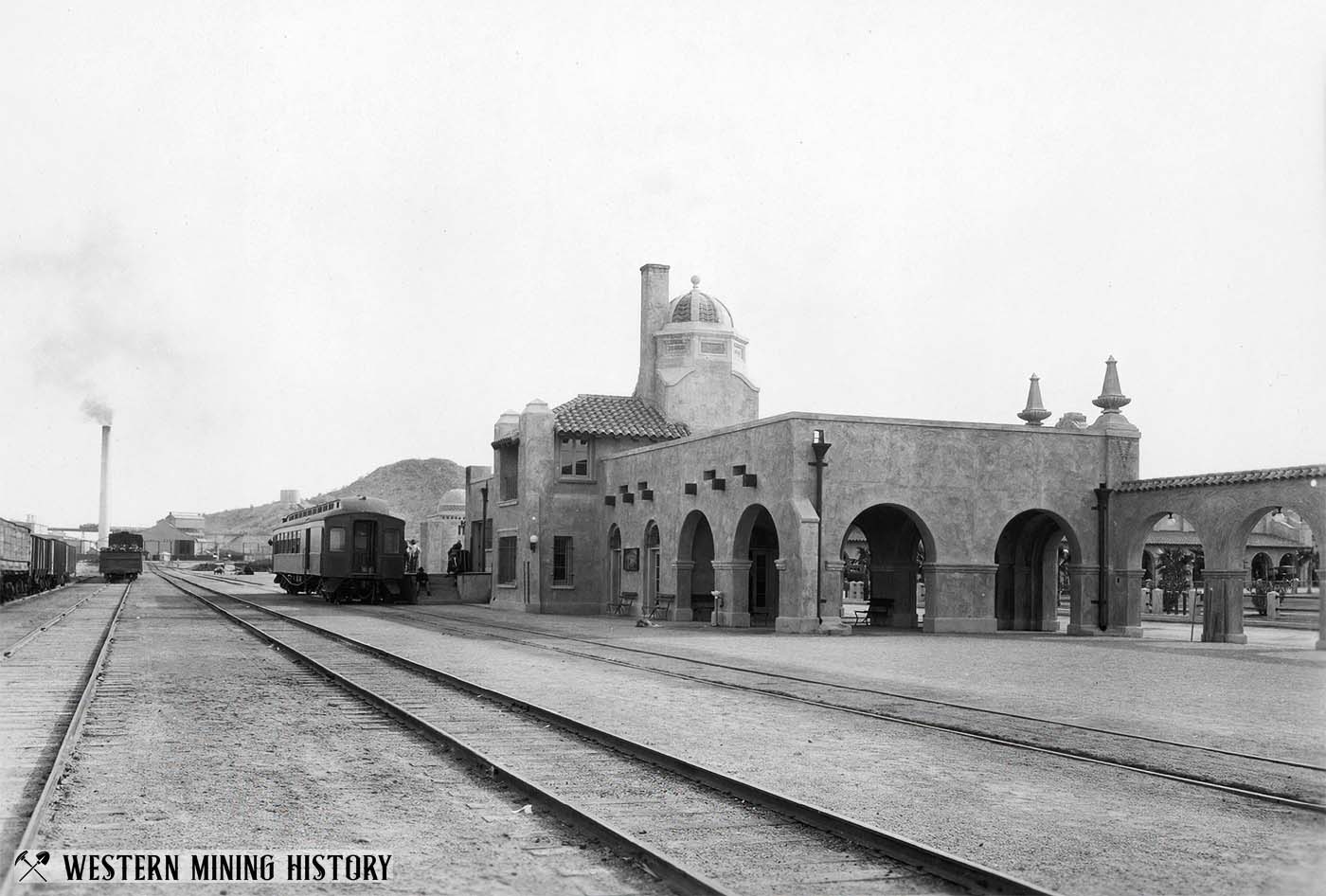

Many of the original company town's buildings, constructed in the Spanish Colonial Revival style, still stand today as enduring symbols of Ajo’s heritage. Notable examples include the plaza and train depot, both built in 1916, and the Curley School, completed in 1919.

Arizona Mining Photos

View over 35 historic Arizona mining scenes at A Collection of Arizona Mining Photos.

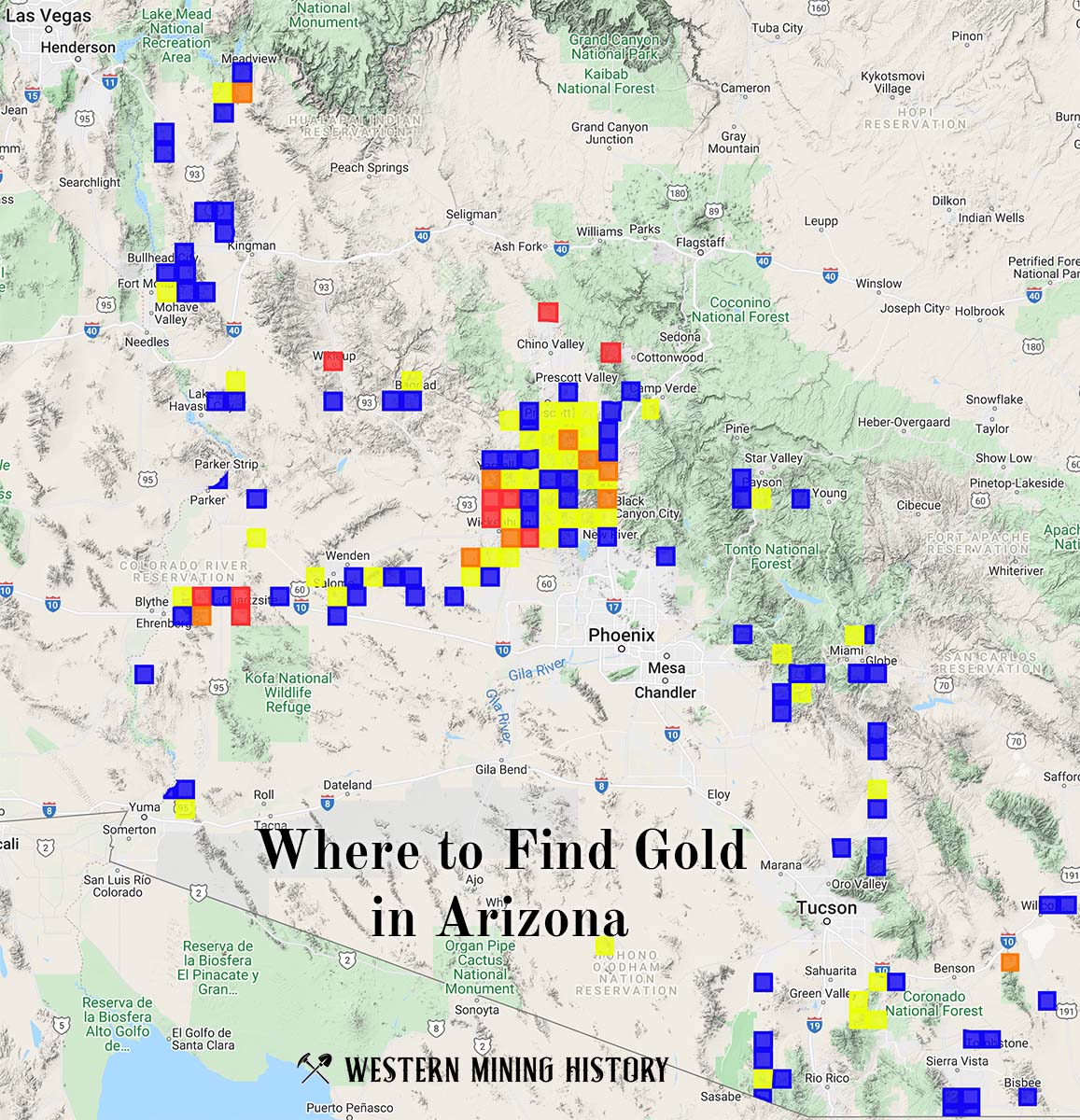

Arizona Gold

"Where to Find Gold in Arizona" looks at the density of modern placer mining claims along with historical gold mining locations and mining district descriptions to determine areas of high gold discovery potential in Arizona. Read more: Where to Find Gold in Arizona.