Crested Butte History

Prospectors were present in the Elk Mountains region of Colorado as early as the 1860s. However, the remote and harsh nature of the high Colorado mountains, combined with often hostile encounters with Native Americans, discouraged the formation of settlements for many years.

Following the removal of the Ute Indians from Colorado (starting in the 1870s), miners, prospectors, businessmen, and settlers of all types started pouring into the Colorado mining regions.

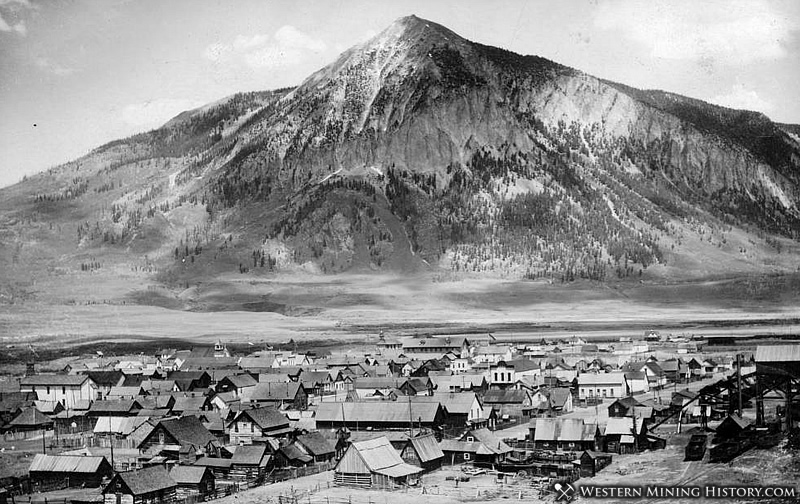

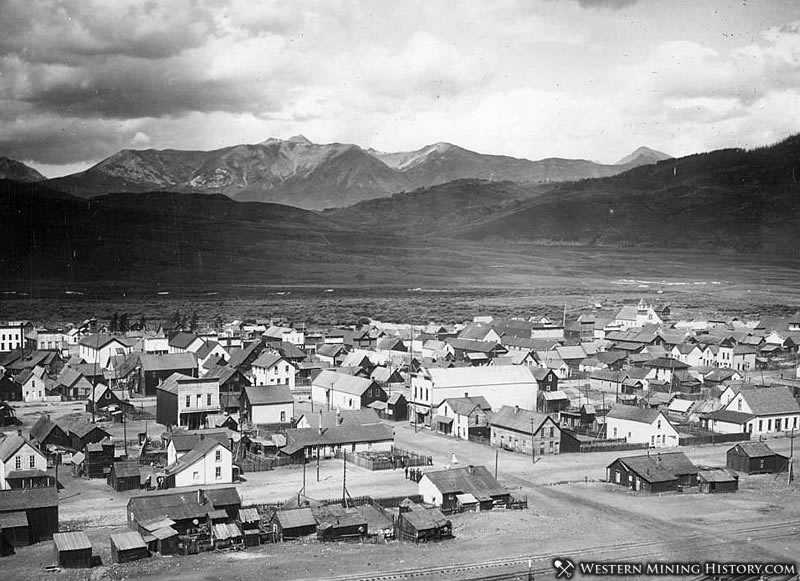

Crested Butte was laid out in 1878 by Howard Smith, and was incorporated in 1880. The town was aggressively promoted as the supply and commerce center of the Elk Mountain region’s numerous mines and camps. The town grew quickly and a population of over 400 was reported in 1880.

Crested Butte was also the location of coal beds. While the prospect of coal mining was not as glamorous as the silver mines of nearby camps, coal would keep the town prosperous long after the silver camps died out.

Former President Ulysses Grant came through in August 1880 as part of a tour of Colorado mining camps. Grant was reportedly impressed with the coal deposits of the area.

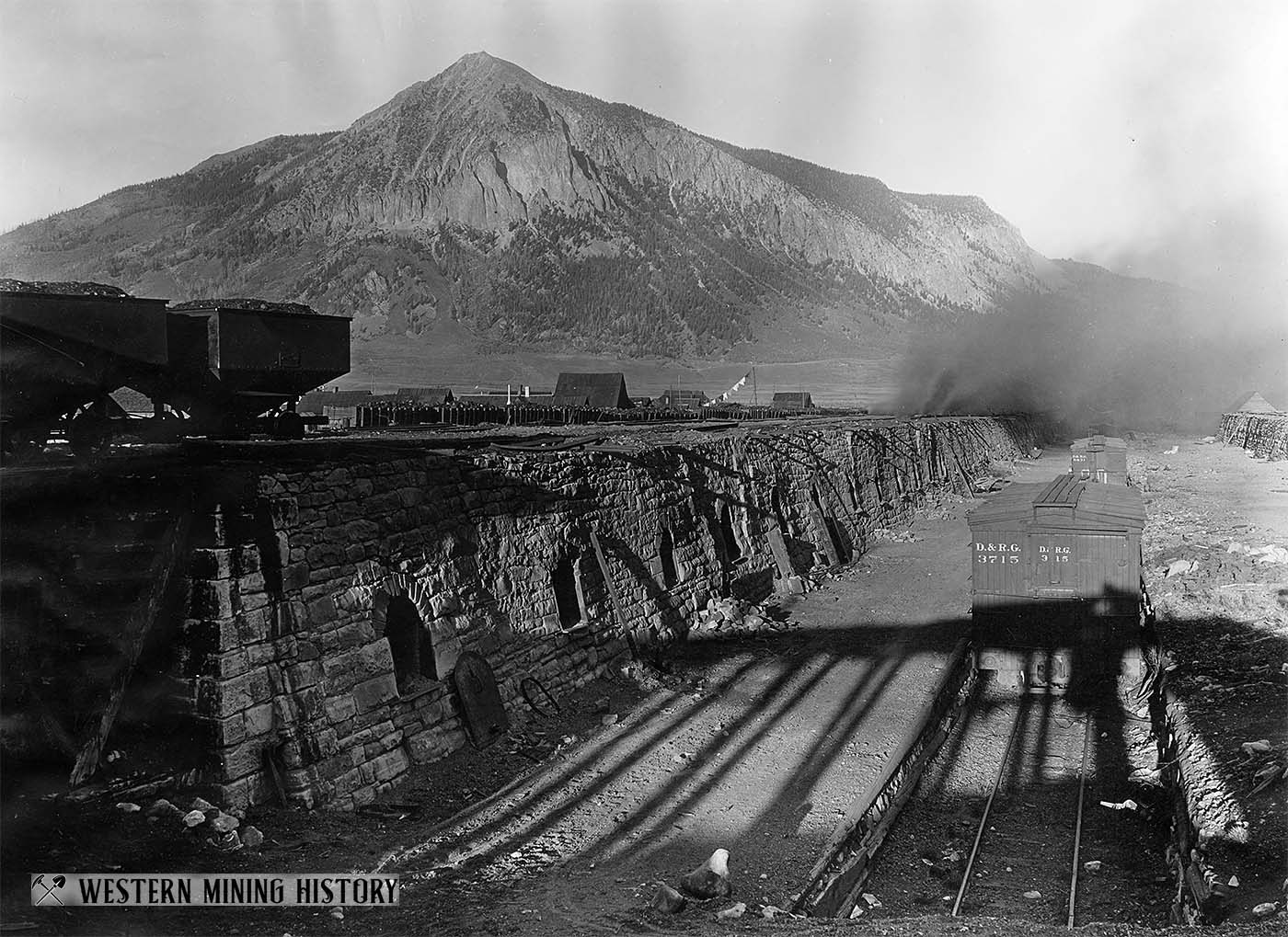

The town’s location in a wide and pleasant valley that was central to many mining camps, along with the presence of abundant coal, attracted a branch line of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad. Construction of the line was completed in November of 1881, ensuring that Crested Butte would be the region’s center of commerce.

The arrival of the railroad further stimulated the growth of the town. In 1882 Crested Butte had over 1,000 residents, and counted a bank, five hotels, several saloons, and three livery stables among its numerous businesses.

Coal mining began in the area in 1881, and throughout the 1880s and 1890s coal was Crested Butte’s primary industry. Early coal miners in the area were Anglo-Saxon from Wales, Scotland, Germany, Ireland and Cornwall. In the 1890s many Greeks, Italians and Slavs from Southern Europe began arriving to work the mines. As a result Crested Butte became a diverse town of immigrants, and many lodges and fraternal orders were established among the various groups.

The Jokerville Mine Disaster of 1884

The Jokerville mine, opened in 1881 by the Colorado Coal and Iron company, was one of the area’s top coal mines. By 1884 the mine had around 120 miners working day and night.

Webmaster's note: although the mine at the center of this disaster is widely acknowledged as being called Jokerville, that name doesn't appear at all in historical newspaper articles. The origin of the name and when the mine started being referred by it are a mystery.

On January 24, 1884, shortly after the day crew had entered the mine, a devastating explosion occurred. The shock of the blast could be felt a half mile away, and smoke poured out of the mine portal.

The Jokerville’s night crew of miners returned to the site of the blast, along with miners from a neighboring mine. Rescue attempts were halted by the poisonous gas pouring out of the mine, and the helpless miners could do nothing but wait until fans were repaired and the air to the mine restored.

When rescuers were finally able to enter the mine, a devastating scene awaited them. Nearly all of the Jokerville’s day crew had been killed, a total of fifty-nine men.

The Jokerville portal was reopened in May of that year, then closed permanently a year later when a new portal was finished at a higher location that was deemed safer.

A newspaper article from 1884 that describes the disaster is included lower on this page.

Coal is King

In the months following the disaster the coal miners returned to work and eventually some sense of normalcy returned to Crested Butte. The local coal mining industry continued to prosper and grow through the 1880s, and by 1891 the mines employed over 500 men.

1891 saw a violent strike against the coal company after miner’s wages were reduced. The strike didn’t last long, with the miners relenting without their demands being met. Subsequent strikes in 1913 and 1927 lasted longer, but always ended the same way for the miners. The Colorado Fuel and Iron Co. (formerly Colorado Coal & Iron), had an iron grip on the Colorado coal industry and was time and again able to thwart the demands of striking miners.

CF&I opened its “Big Mine” coal operation in 1894, which would be Crested Butte’s primary producer for decades to come.

Compared to most of the metal mining districts in Colorado which often had boom and bust periods measured in just years, or a few decades for the more famous ones, Crested Butte remained an active coal town for over 70 years. The Big Mine finally closed in 1952, ending Crested Butte’s status as one of Colorado’s longest-lasting community of miners.

Transition to Tourism

With Crested Butte’s mines idle, there was no longer justification for the maintenance of a rail line and the branch was closed in 1955. Many residents left during this period to seek jobs elsewhere.

The beautiful setting attracted the interest of outside groups and by the late 1950s the transformation of the coal town’s economy to a tourist destination began. In 1958 the Law Science Academy was founded, establishing scientific educational programs for doctors, lawyers, and their families during the summers.

In 1962 the first ski resort was opened - that resort has grown into Mt. Crested Butte, the area's largest ski resort. Today Crested Butte is a popular and vibrant tourist destination. Know as “the wildflower capital of Colorado”, the town is popular with both winter and summer tourists.

The Crested Butte Horror

The following article from a February 2, 1884 edition of the Silver World newspaper describes the tragedy of the Jokerville mine disaster.

We have not the heart to write the full details of the terrible disaster at Crested Butte, referred to in the few lines received as we went to press last week. It is the most awful calamity that ever visited the State. By it 59 men, a large number of them men of family, were launched into eternity. Their blackened, bruised and crushed bodies were not recovered until Saturday and Sunday, and several of them were unrecognizable.

The explosion was caused by a Swedish miner carrying an uncovered light into one of the chambers of the mine, which being filled with fire-damp immediately exploded tearing away the fan which furnished air to the mine, the timbering of the mine and its approaches and filling every street and chamber with debris which the imprisoned miners who were not killed outright could not pass, and barring out help from the outside, until the doomed men within were suffocated with the deadly gas which soon filled the chambers.

The fan was repaired after a stoppage of about nine hours and air forced into the mine with the vain hope of saving some lives, but when, after thirty-six hours, the first chamber was reached and the horrified searchers found seventeen bodies piled upon each other all hope fled.

At the end of the third day’s search all that remained to do was to lay 59 ghastly corpses side by side on the platform prepared for their reception. Words cannot describe the scenes which followed when wives, mothers and orphaned children were permitted to receive all that remained of their loved ones. It must have been distressing beyond imagination.

The funeral took place last Tuesday, the Masons and Odd Fellows of the town and of Gunnison caring for their dead brethren, and the clergy of the several denominations performing the last sad rites over the others. All expenses were paid by the C. C. & I Co., and General Palmer telegraphed $1,000 from New York to supply the immediate wants of the families of the deceased.

The names of the killed were: Henry Anderson, John Williams, M. J. Stewart. John Martin, Thomas Rogers, James O’Neil, Jacob Laux, John Anderson, James Walsh, Peter Baker, William Davison, Richard James, David Hughes, P. McManus, W. T. King, John Creelman, John Hular, Thomas Williams, John Shun, Pat Barrett, John McGregor, John Myers, F W. Smith, G. B. Nicholson, William Maroney, Nick Probst, Thomas Laffev, John Price, James Driscoll, James Coughlin, Henry Stewart. B. Heffron, L. P. Heffron, W. L. Jones. John Donnelley, Carl Rodewald, Charles Sterling, Thomas Roberts, Jim McCourt, Fred Becht, Iber King, Joseph Weisenberg, H. Donegan, Joseph Kranst, James F. Stewart, Jr., William Neath, Morgan Neath, Thomas Glancy, John Rutherford, William McCowitt, A W. Godfrey, Dan McDonald, William Aubrey, Ben Jefferies, Thomas Stewart and four unrecognized.

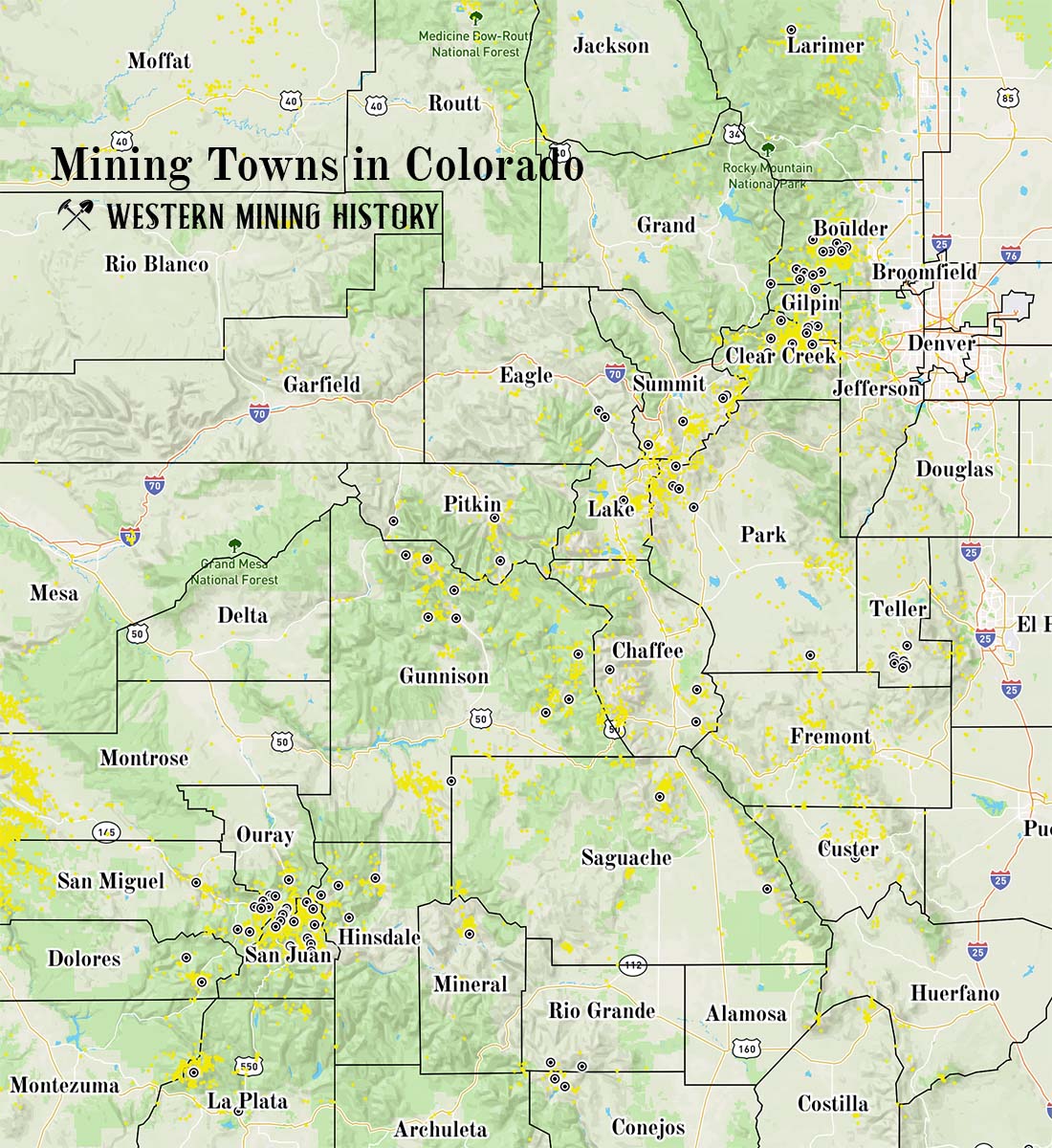

A Tour of Colorado Mining Towns

Explore over 100 Colorado mining towns: A tour of Colorado Mining Towns.

Colorado Mining Photos

More of Colorado's best historic mining photos: Incredible Photos of Colorado Mining Scenes.