Idaho Springs History

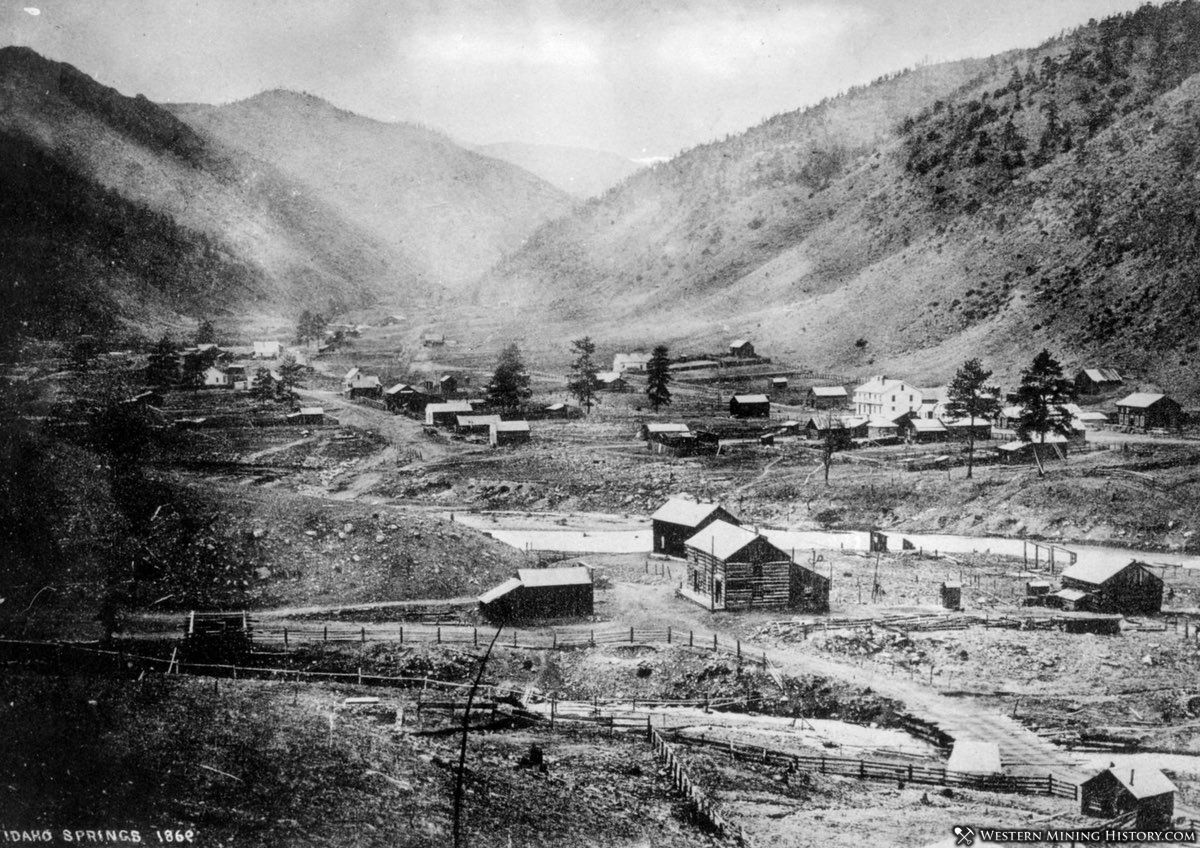

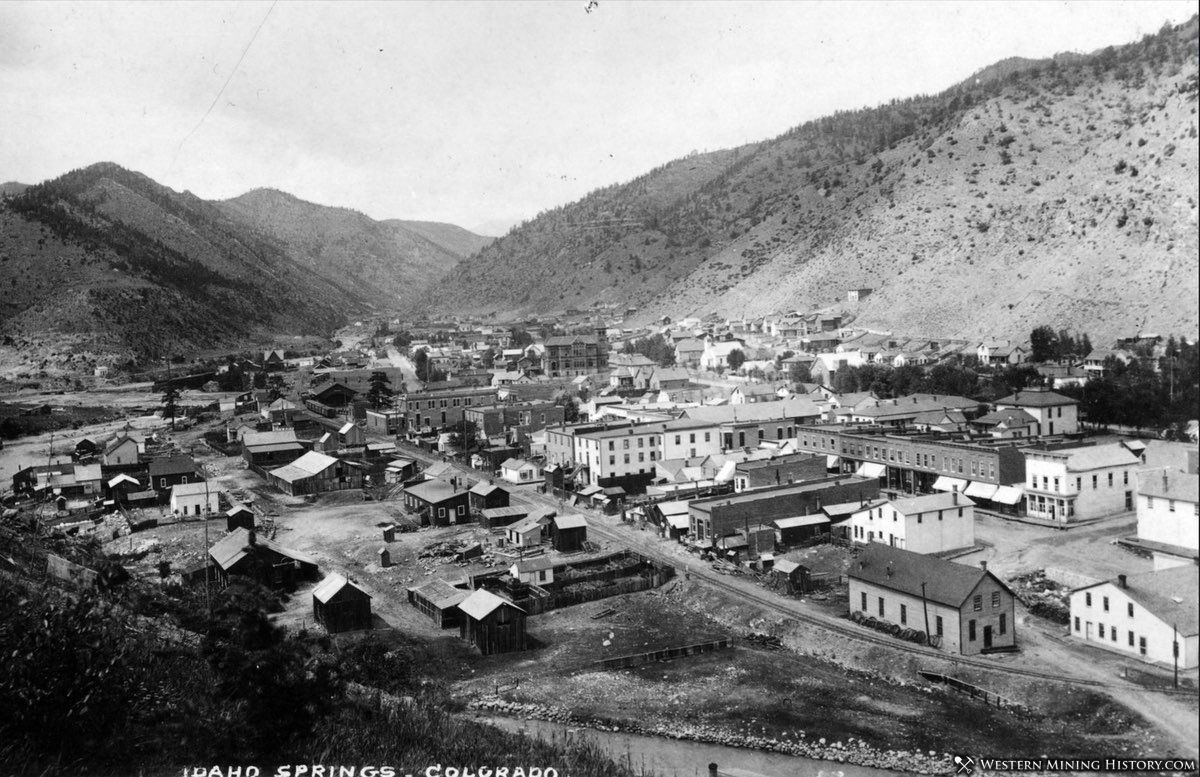

Idaho Springs is the site of the first significant gold discovery during the Colorado Gold Rush. George Jackson found gold at the confluence of Chicago and Creeks on January 7, 1859.

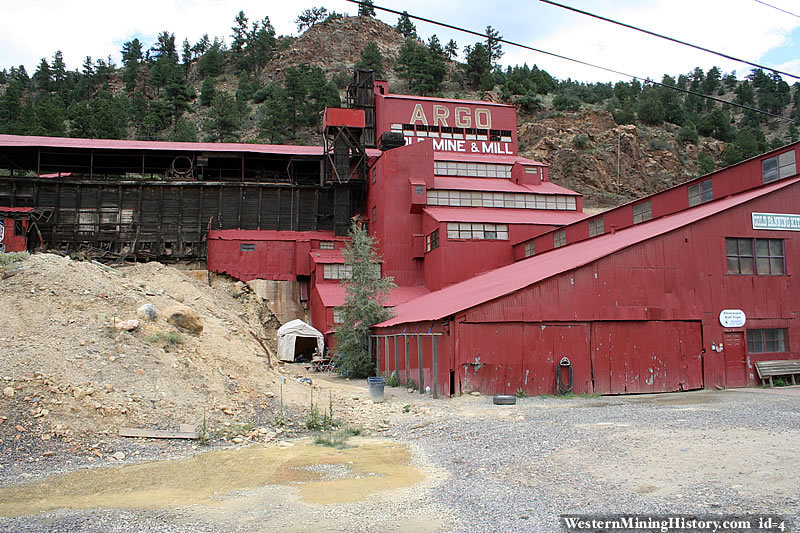

Idaho Springs is the site of the terminus of the Argo Tunnel and the Argo Gold Mill. The Argo Tunnel extends over four miles from Central City to Idaho Springs, under an area of extensive mining. The purpose of the tunnel was to drain problematic water from overlying mines, and to provide a direct route to ship ores from the mines to the Argo Mill. The tunnel took 17 years to complete and was the worlds longest tunnel when completed in 1910.

Today, Idaho Springs is a popular tourist stop along Interstate 70.

Early History and Mines

Text in this section was written by Ellie Frost

Twenty-four year old George Andrew Jackson, emigrant from Missouri and cousin of Kit Carson, first discovered gold on the shores of Clear Creek in what is now Idaho Springs on a winter day in January of 1859. After mining from 1853 to 1857 in California, he returned to Missouri with suspicions that gold lay around Laramie and returned west in 1858. Weeks of prospecting yielded no results, and in September the group heard about gold around Cherry Creek, presumably the discoveries by William Green Russell in Montana City (near modern day Santa Fe and Evans Ave in Denver).

The group first found traces of gold off the St. Vrain River and settled in the Greeley area (then Thompson’s Fork). Jackson moved further south to Arapahoe (near Coors Brewing in Golden), and soon grew bored with hunkering down for winter, becoming convinced he could find gold in the creeks of the mountains.

Several failed attempts to reach the Idaho Springs valley due to deep snow stopped his progress into the mountains. January 1st, 1859, he went out to hunt, packing nothing more than “his rifle, three biscuit, a tin cup, a buffalo robe and a blanket, intending to remain out two or three nights” (The Western Mountaineer, December 14, 1859, an article based on Jackson’s journal) and happened upon a large band of elk. He followed them into the mountains up Clear Creek Canyon (Vasquez Fork of the South Platte River), hoping they would lead him to an area with gold potential. Over three days they traveled about 12 miles, with Jackson following them from “a respectful distance”. The third night he looked out over the valley he sought and awoke in the morning covered in more than 2 feet of snow.

After traveling further up the creek for a couple days, he reached the mouth of Chicago Creek where he started a fire, intending to thaw the ground enough for prospecting. On January 6th, he and his dogs fought off a wolverine, which wounded the dogs. The next day, he “Removed fire embers, and dug into rim on bed rock; panned out eight treaty cups of dirt, and found nothing but fine colors; ninth cup I got one nugget of coarse gold. Feel good tonight. Dogs don’t. Drum is lame all over; sewed up gash in his leg tonight – Careajou no good for dog.” That nugget was enough to convince him to head back to Arapahoe with his mouth shut, tending to his injured dogs, and preparing for his return in May with a prospecting party and additional supplies.

Jackson's party, now thirty men, set out on the second of May, “cutting their road as they went” enroute to “Jackson’s Diggings”. Twenty five dollars worth of coarse gold was found on the first day, but on the tenth day, word arrived of discoveries in Gregory's Gulch, which drew Jackson away from his discovery at Idaho Springs. John Gregory and party had been on their way to Jackson's strike when they took a wrong turn and ended up making an even richer discovery in the area that would later become Central City. Jackson left Idaho and worked the new discoveries for some time. He then went on a series of prospecting tours through the mountains, never returning to his namesake diggings.

Flash in the Pan

On May 9th, 1859, a Miners Meeting appointed a chair, and committee, and set by-laws and resolutions for the establishment of a new mining district:

- Sec. 1. Each claim shall be fifty feet front by two hundred deep.

- Sec 2. Every claim shall be marked and staked with at least two stakes and shall be improved within ten days after taking.

- Sec. 3. The discoverers of new diggings shall be entitled to one extra claim.

Within the first few weeks of May 1859, over 300 men were working in the area and rumored to be making 3 to 8 dollars a day, at a time when the national average was just $2 a day. Although one of the richer discoveries was made on Chicago Creek (named for a group of prospectors known as the "Chicago Party"), many still referred to the area as Jackson’s Diggings, though Jackson himself had long since moved on. Before the name Idaho Springs was established, the area was also known as Idahoe, Clear Creek, Sacramento City, Idaho Bar, Spanish Bar (western end of Clear Creek mined by Mexicans), and Paine’s Bar.

Placer mining around Idaho Springs continued from 1859 to 1913, with the majority of gold recovered in the first three to four years after discovery. Crude arrastras were built as early lode-mining work was attempted. In 1861, a 20-stamp mill was built to process ore from the Whale, Lincoln, and other lode mines in the area. Though there was gold in Idaho Springs, larger discoveries took a great deal of the attention, with miners heading to Central City, Empire, and Georgetown, as well as continuing deeper into the mountains.

The Colorado mining industry was still in its infancy when a depression hit, fueled by the difficult transition to lode mining of the complex local ores, and the onset of the Civil War. By 1866 many of the lode mines were inactive, but some of the more notable mines like the Seaton, Crystal, Whale, Lincoln, Edgar, and Freeland continued to operate..

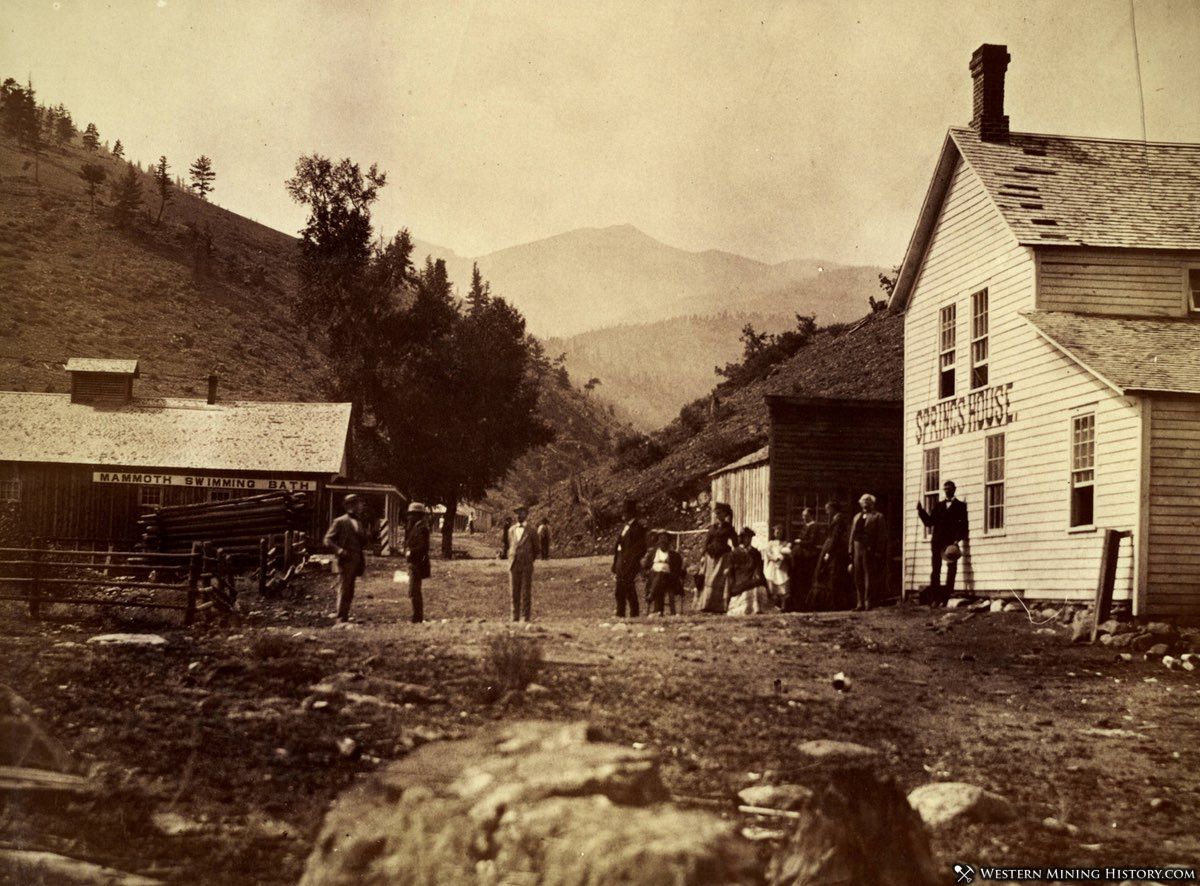

Healing Waters

It didn’t take long for the hot springs to be developed with hotels, pools, and bath houses. In the beginning of 1864, Dr. E. S. Cummins, Hydropathic Physician, constructed a bath house over the soda springs, boasting benefits for rheumatism and other complaints, as well as a restaurant. Before the end of the decade, another bath house had sprung up in the area and Idaho Springs became synonymous with the Idaho Hot Soda Springs.

In 1870, a chemical analysis of the water showed carbonates of soda, lime, magnesia, and iron, sulphates of iron, soda, and lime, and chlorides of sodium, calcium, and magnesium, as well as traces of silicate of soda. Chemist J. H. Pohle deemed it an antacid alternative, with laxative properties, noting it was beneficial for rheumatism and diseases of the skin.

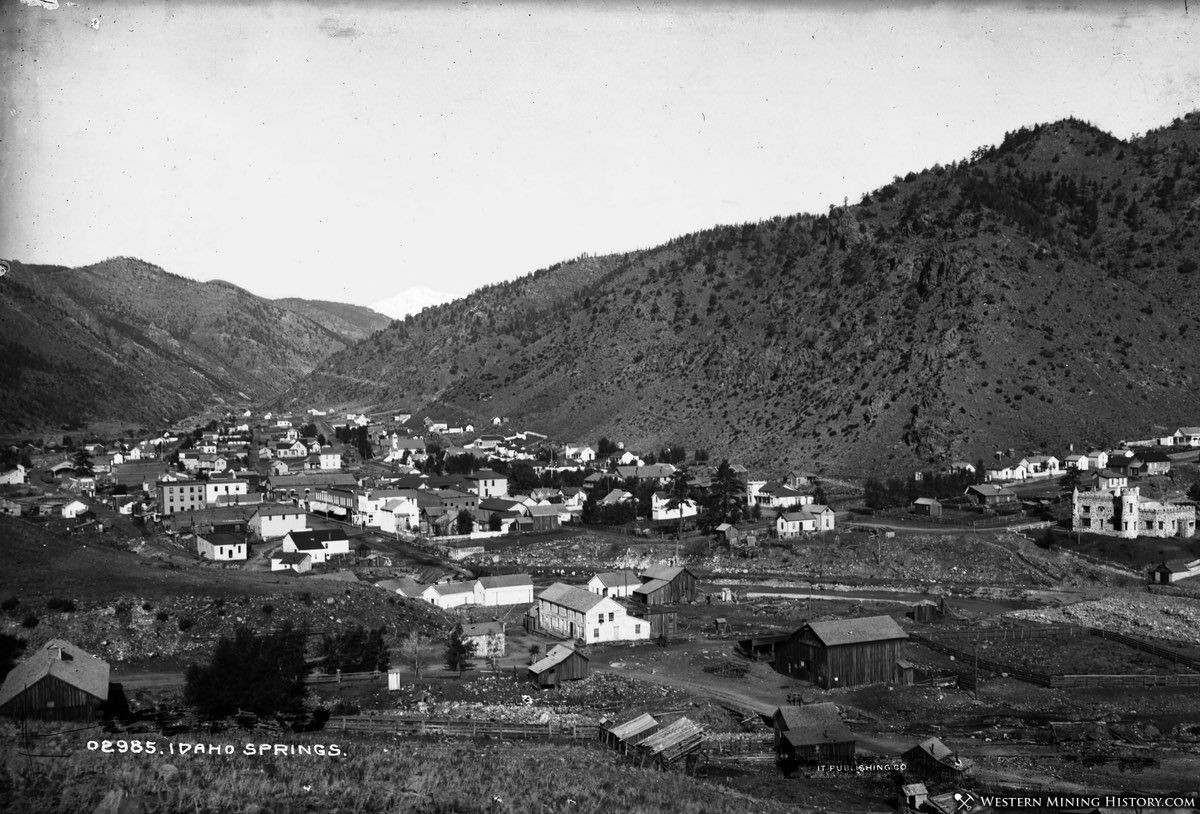

A Stable Mining Community

By the 1870s the Colorado mining industry was back on its feet, fueled by eastern capital that started flowing again after the conclusion of the Civil War, and by improvements in milling and smelting technology. The railroad arrived at Denver in 1869, and the 1870s saw spur lines built to the major mining centers, greatly stimulating mining operations throughout the state.

While Idaho Springs was overshadowed by it's booming neighbors Central City and Georgetown, it still grew to be an important mining city. An October 17, 1885 edition of the Colorado Mining Gazette described the local mining industry:

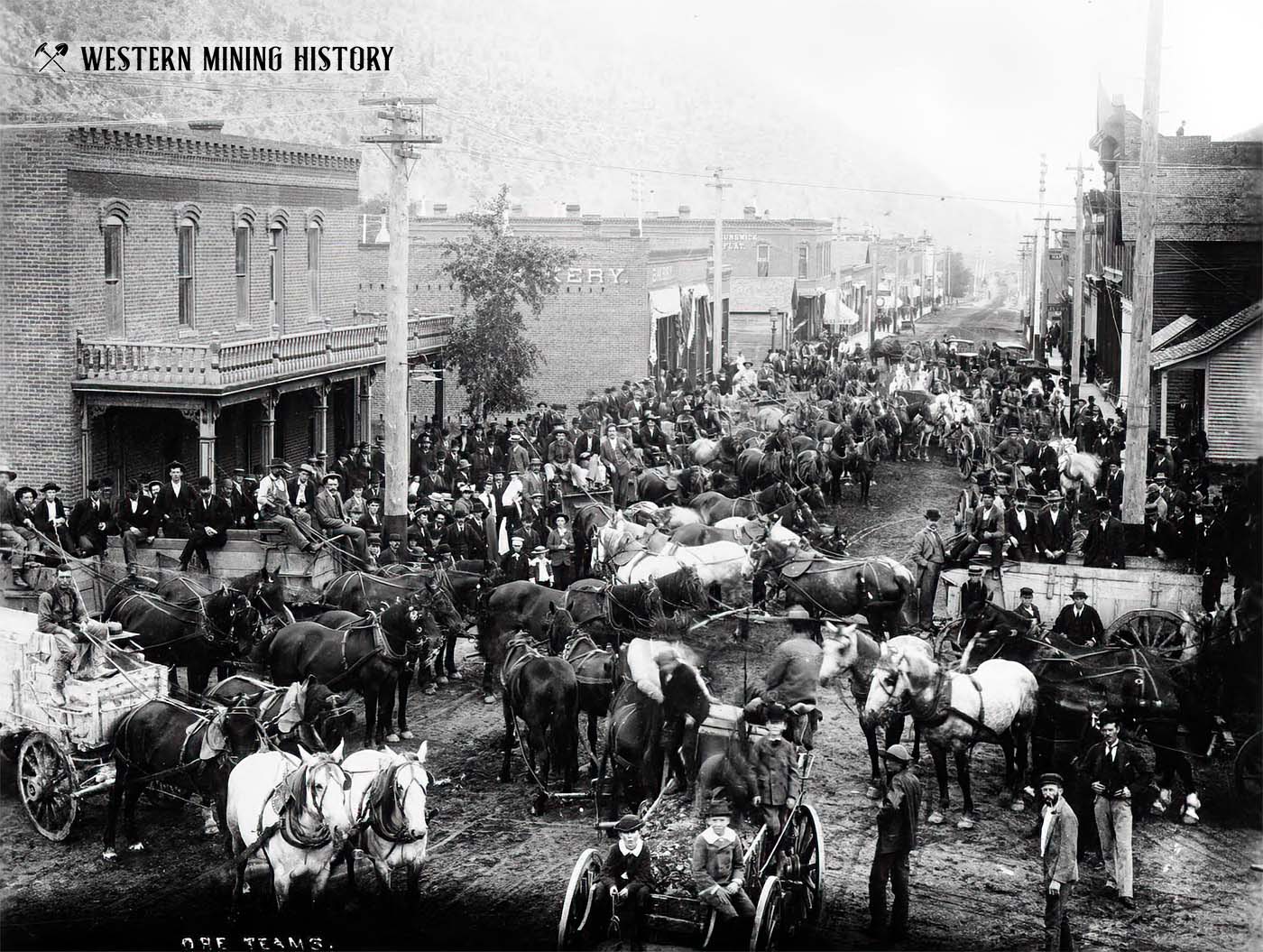

Idaho Springs dates its birth as a town and mining district twenty-five years ago. At that time placer mining was the great industry, and the records prove this vicinity to be second to none in production from its placers. As time rolled on, lead mining became not only fashionable but profitable. The Hukill and the Whale were discovered and developed, followed by the Freeland, Donaldson, Champion, and many others. No boom, characteristic of almost every other mining camp in the State, has ever visited Idaho Springs. Its growth has been sure and steady, and to-day the district contiguous to this town is producing and shipping to the sampling works, smelters, stamp mills and concentrating works 1,425 tons per week, which would be over 5,700 tons a month. The numerous placers being worked, from Fall River to Grass Valley and below, attest the fact that gold is still to be found in paying quantities in the bed of what was once Clear Creek, now only known by that name, as the numerous mills scattered along its course soil its waters and cause the wondering stranger, as he views it for the first time, to imagine it a child of the big Missouri.

Unlike Colorado's other mining boom towns, Idaho Springs was known as an orderly, if not boring community. A September 16, 1882 edition of the Colorado Mining Gazette laments:

There is one drawback to the growth of this beautiful town. Not social dissentions – not lawlessness, - as some might imagine from reading exaggerated and sensational publications elsewhere, magnifying, absurdly, matters of the slightest possible consequence. Indeed, it is a daily comment of intelligent and observable tourists, that despite the fact of Idaho being a mining camp, it is conspicuously as quiet and orderly as the most staid of New England villages, and statistics of the police (only one such office in the town and his office a sinecure) conclusively prove it, for an arrest, even for the most trivial offense, is such a rarity as to startle the entire population....... Inconspicuous as the place has been, having been entirely omitted from most of the maps, except those of recent publication, people on the other side of the plains were generally unconscious of its existence, and those who happen to hear of it for the first time, suppose it to be located in the territory of the same name.

Idaho Springs continued to be a tourist center for decades. A July 1885 article describes the benefits of the hot springs "valuable waters, especially useful in rheumatism, catanous diseases, contraction of joints, syphilis, etc."

Typical of mining towns of that period, Fourth of July festivities included a Fireman’s Tournament of Races (which became a 4th of July tradition in the area), rock drilling competitions, baseball tournaments, and fireworks displays that were attended by people from Silver Plume, Georgetown, Central City, Black Hawk, Golden, Boulder, and Longmont.

Tunneling a New Future

While Idaho City was relatively inconspicuous among Colorado mining cities, it gained fame as the location of the famous Argo tunnel and mill.

The rich mines in the area, including those of the fabulous Central City district, were increasingly burdened with water at depth. Samuel Newhouse, a New York lawyer with many business interests in Colorado, recognized an opportunity to solve the problem of water in the mines. According to a February 4, 1893 edition of the Silver Standard:

Articles of incorporation were filed for the Argo Mining, Drainage, Transportation and Tunnel company by Samuel Newhouse, Andrew Newhouse, and C. C. Parsons. The capital stock is $100,000. The principal office is in Denver, but the company’s operations will be confined to Clear Creek and Gilpin counties.

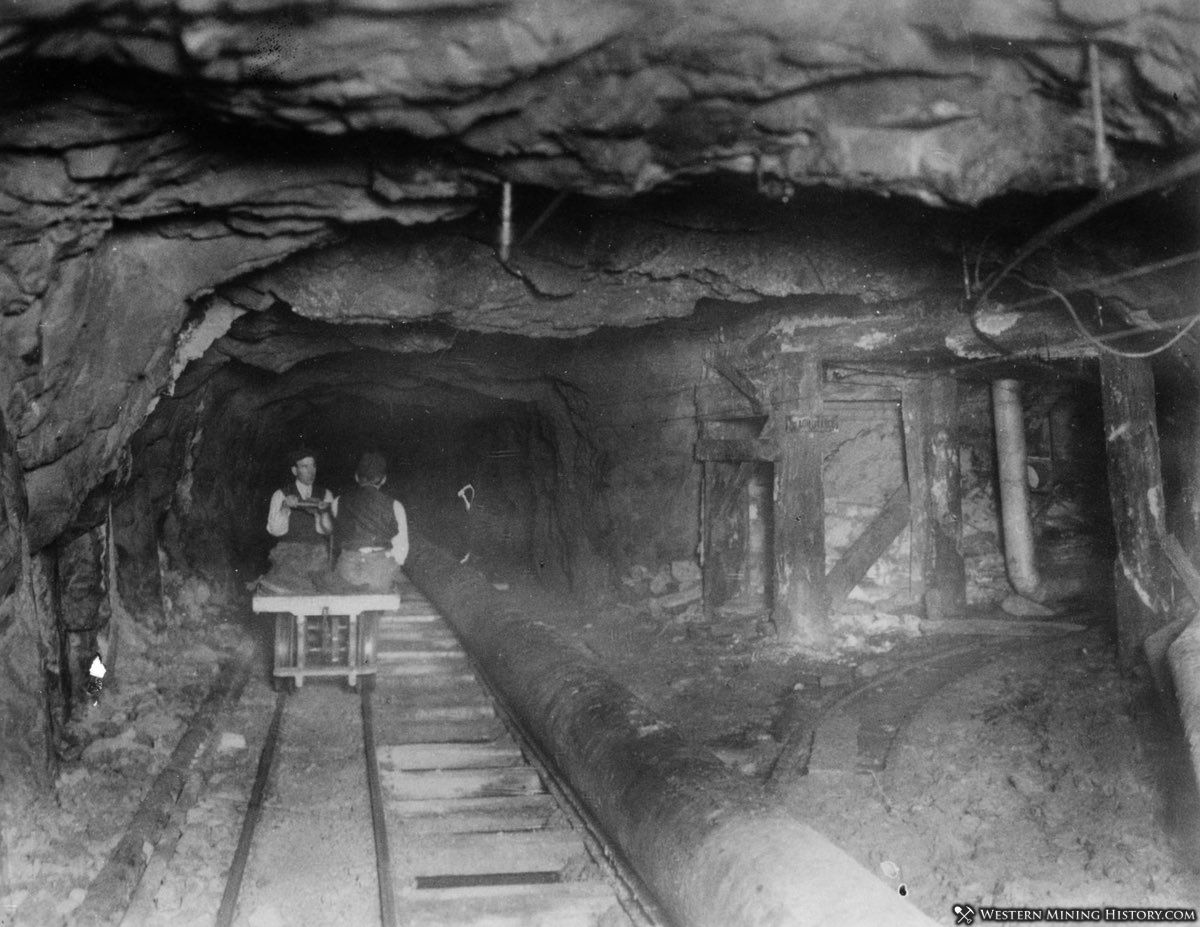

By October, work started on the “Newhouse Tunnel”, with a new road and rail spur being built to the portal. Work was started on the foundation for the engine and compressor and an 80-horse boiler was installed. The plan was to build a 4 mile tunnel from Idaho Springs, extending under the mines of the Central City district. The tunnel would both drain the mines of water and allow ore to be carted out downhill rather than hoisted out of the shafts.

Though he had earned the trust of the English investors, local mine owners were more than hesitant to join his grand enterprise. Newspapers of the time published opinions for and against the tunnel. One published an opinion against the tunnel project:

Do you suppose for a moment that us people who have mine, mill and property interests in Central City and Black Hawk are going to invite the tunnel over here to cheapen the values of our holdings? Idaho Springs has made her brags that the Newhouse tunnel would take half the business away from Central City, and it would do that very thing. Now let me give you a pointer. We may not be quite as metropolitan over there as you folks claim to be over here, but we are by no means d—n fools. The water in our mines is not bother us as bad as it might be, and the pumping system suits us pretty well.

While another newspaper came out in support:

Some people up in Gilpin County … are foolish to believe that the Newhouse Tunnel Company is a device to rob them of their mines. If the people would stop and think a minute, they would see the absurdity of the proposition. At the price for which any mine owner would be glad to give for the privilege of working his property through the Tunnel Company, he should realize he will receive this price back. This is hardly trying to rob the owners of their mines.

Whether or not mine owners were on board with the project, the tunnel was not going to be completed quickly. Late in 1894 construction stopped when tensions boiled over with Superintendent at the time, Lou R. Johnston, who quickly decided to sell his interests. Newhouse returned to England for three months in early 1895, securing a rumored additional $500,000. Over the summer, work started at the Central City side, while the Idaho Springs side had reached nearly a mile in length.

It was determined that the addition of a mill at the tunnel portal was needed to improve the projects profit potential. Newhouse returned to Europe in the fall to continue seeking backers for the project.

In 1897, after 4 years of construction, the tunnel still had not brought any income to investors. Work shifted to mining lodes found along the way in a bid to generate revenue. The project may have never been completed under a less-accomplished leader, but Newhouse was determined to see it through. The sale of his one-third interest in the Highland Boy mine in Bingham, Utah to Standard Oil's John D. Rockefeller for $4,000,000 established him as one of the World's leading mining men, with the Durango Democrat stating he was “building up a world-wide reputation as a successful manipulator of big mining enterprises” (June 18, 1899).

The tunnel entered Gilpin County in the spring of 1900. As the work neared Central City, a frustrated Newhouse shut the tunnel construction down for a full year, starting in April of 1902, with backers angry that no contracts had been signed with Gilpin mine owners. Many mine owners believed they would still get the benefit of drainage from the tunnel without paying into the project. Though construction had stopped, mining continued on the mineral deposits revealed during tunneling.

Construction commenced in April of 1903, and it was seven more years before it was completed. Finally, on November 18, 1910, the last round of shots was fired, connecting Clear Creek and Idaho Springs after seventeen hard worked years, at a total length of 21,968 feet (over four miles), and a cost of around $5 million dollars. The Argo Tunnel inspired many others around the state and the Rockies, with many other mining enterprises learning the lessons of the Argo project.

The Argo in the 1900s

After the tunnel was completed, work on the mill began in June 1912, and was processing ore by 1913. Gem Mining Company general manager and Colorado Senator, William E. Renshaw purchased the tunnel from the Argo Tunnel Mining and Milling company in 1921 for just $250,000. The tunnel and mill continued working the mines of Seaton Mountain up until 1943.

One day in January 1943, while men were working on draining the Kansas mine, a wall of water was unleashed that killed four men and sent a massive column of water and rock out into the valley. The force of the water shot a full ore cart from about 100 feet from the entrance of the cave to where the modern day Safeway grocery store resides, and the drainage caused Clear Creek to shift across the valley. The accident coincided with the government shut down of gold mines during World War 2, and the Argo tunnel never again serviced the mines of the area.

After sitting abandoned for decades, the mill and tunnel were purchased in the 1970s, restoration began, and the site was added to the National Register of Historic Places. Today the Argo mill is a museum, and the tunnel is sealed about 150 feet from the entrance but water continues to drain from the hundreds of mines it connected to. The water is pumped through the Argo Tunnel water treatment facility and then released into Clear Creek.

The Fabulous Phoenix Mine

Discovered in 1871 and patented as the Phoenix No 1, and No 2, and Phoenix Mill Site in 1875, the mines did not see much success in the 19th century. Once sold for back taxes of $20 to a real estate developer, the Phoenix was then sold for $5,000 to a Minnesota farmer named Gunderson in 1934. Prior to World War Two when the mines were shut down, Gunderson became a rich man working the Phoenix Vein. In the 1950s, Al Simmons, under a lease from Gunderson, cleaned up many of the old stores within the mines producing large amounts of gold from unprocessed ore.

The mine was purchased in 1972 by Alvin Mosch, the Mosch family worked the mine on as large a scale as they could for years, hoping for gold and silver prices to rise and it to be profitable enough to work the vein.

Before purchasing the mine, Alvin met his wife Patricia in a mine up Virigina Creek near Idaho Springs in 1957. Twelve years later in 1969, she became the seventh female graduate of the School of Mines in Golden, and the first to graduate with two degrees in two separate fields in one year, one in geological engineering and another as a masters in mining engineering.

“There was more than a little resentment from the boys at Mines, they would help each other, but they wouldn’t even begin to help us girls [only 2 in her graduating class], so we just had to study harder. I may be a better geologist because of that” (Golden Transcript, January 26, 1977) She became a senior geologist and pioneer in the oil shale industry, and the first female member of the Clear Creek Mining Association, raising their children in the shade of the Phoenix tunnels as she completed her studies.

“When I was 8 years old, she took me to one of her classes. That alone made me decide that one day I would become a Mining Engineer. Thirty-two years later, I became the manager of the CSM Experimental Mine and even instructed the same Mining Engineering Lab and Surveying classes my mother once took.” – Dave Mosch. Dave, current owner of the Phoenix, has become a legend of his own account in the mining world, with a degree in mining engineering and a literal lifetime of experience working inside the earth as a geologist, mineral processing engineer, and environmental engineer.

On Labor Day 1975, Dave, a ninth grader at the time, found the astounding Resurrection Vein. The bright blue copper oxidized vein was heralded at the time as the “biggest find Idaho Springs has had in recent years” (Golden Transcript, August 15, 1975). Recent surveys indicate that the vein may be as long as five miles, but ore production can't begin until the permits required by the Colorado Division of Reclamation and Mine Safety are obtained. Until the owners can secure those permits, the visitors to the mine are the lucky ones getting to pan the spoils of this beautiful example of Colorado geology.

The mine is rich in gold, silver, quartz, rose quartz, garnet, and citrine, and gives the public a personal experience in the thrill of finding riches from the local hills. Visitors to the mine can witness the stunning geology, manmade stopes and winzes, all variety of historical mining tools, machines, and cart tracks. Well worth the trip from Denver, visitors will be in awe of the gorgeous Resurrection Vein and the other treasures found at the Phoenix Mine. As they say, “gold rides the iron horse”, and the iron throughout the tunnel shows the aspiring miner exactly the secrets they may wish to find in the ground themselves.

Information on visiting the Phoenix Mine can be found on their website.

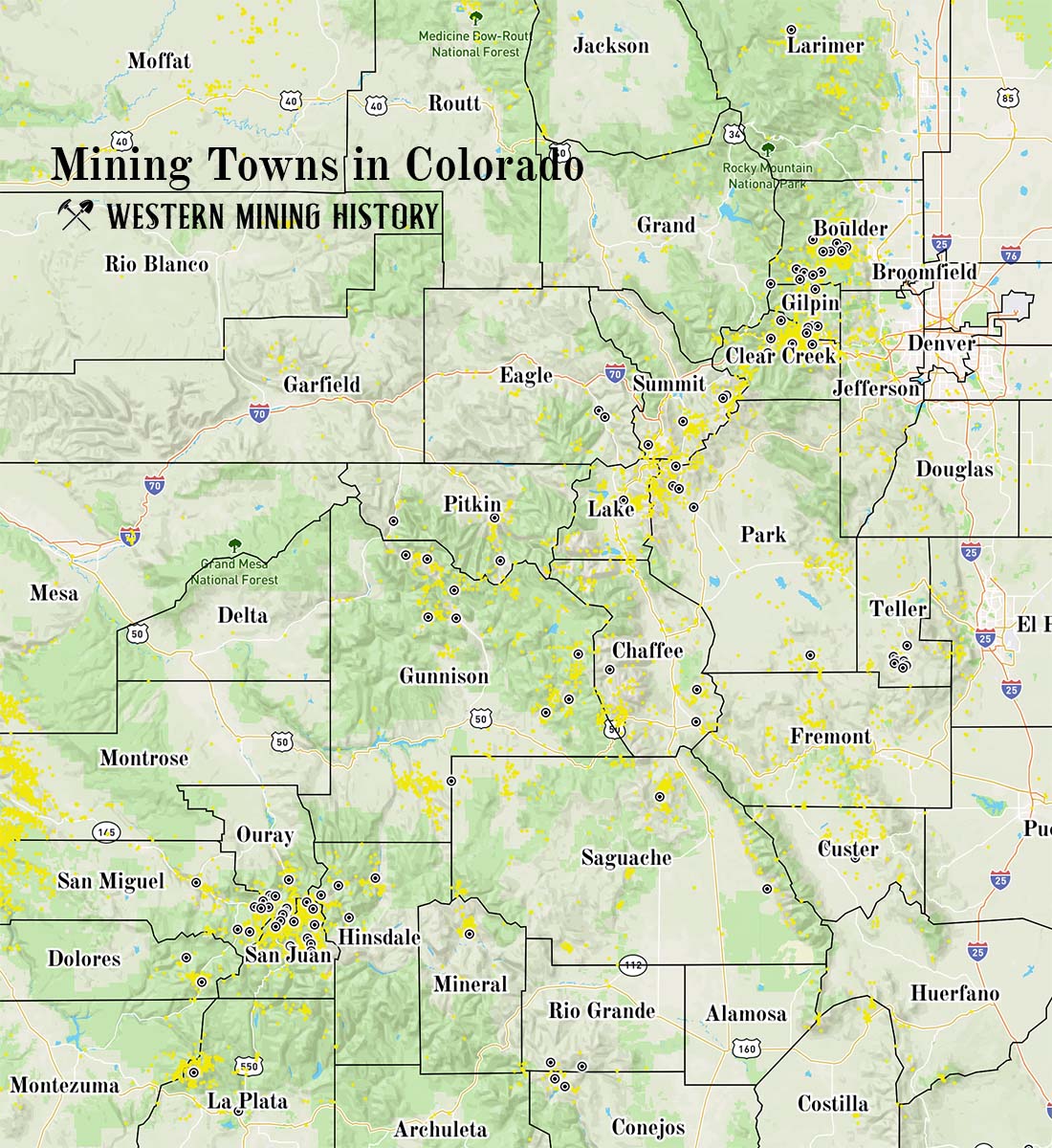

A Tour of Colorado Mining Towns

Explore over 100 Colorado mining towns: A tour of Colorado Mining Towns.

Colorado Mining Photos

More of Colorado's best historic mining photos: Incredible Photos of Colorado Mining Scenes.