From Harpers New Monthly Magazine, 1888 by Edwards Roberts

From Helena to Butte is only a half-day's ride. Leaving the one early in he morning, you are at the other by noon. The journey is extremely interesting. The route is westward, by the Northern Pacific, over the main divide of the Rocky mountains to Garrison, and from there southward, through the fertile Deer Lodge Valley, to the city of mines, smelteries, and steep hills. For an hour after leaving Helena the road traverses the Prickly Pear Valley. Westward rise the Rockies, seemingly impossible, and in the southeast Helena is seen nestled in its winding gulch, and creeping out upon the lowbrowed hills.

The air is so clear that objects fifty miles away seem close at hand. By degrees the grade becomes steeper, and leaving the valley, one finds himself among the gigantic cliffs and buttresses of granite that form the foundations of the huge natural wall that stretches north and south from British Columbia to the borders of old Mexico. Then comes the Mullan Tunnel, long and dark, through which the train passes to the western side of the divide, where the slopes have a pastoral beauty in strange contrast to the appearance of those on the east.

At last we are literally among the mountains. Tall peaks surround us; the pines choke the winding valleys that we follow; clear streams of water flow past us; we enter park after park. The coloring is exquisite, and so varied that one cries out with delight. Strangely fashioned monuments of red and yellow sandstone, grim cliffs of dark basaltic rock, rich green masses of firs and pines, surrounded by dull brown grasses, and scattered over the slopes the bright patches of the quaking asp, colored by the early frosts, and as beautiful as the New England maples after their first encounter with the chilly nights of fall.

The Deer Lodge Valley is of varying width, and contains a large area of agricultural and natural hay lands. The chief towns are Deer Lodge and Anaconda, the latter having a population of 5000. The smelting-works at Anaconda are said to be the largest in the world, and cover nearly fifteen acres of land.

The city of Butte does not claim to be picturesque. It is an interesting place, however, as one so rich and productive and energetic must be, and from the top of its high hills the view of distant mountains does much toward making one forget the disagreeable features of the city itself. The very activity of Butte is sometimes wearisome. It never ceases. By day and night the tall chimneys at the mills are pouring forth there smoke sand flame; the stress at all hours of the day and night are filled with moving throngs.

Money-making is the evident passion of the day. In the race for it all else is forgotten. The city covers the slope of a steep, rocky hill, overlooked by a bare butte, from which the town derives its name, and for the most part the houses are set down at random, and present a heterogeneous collection of wooden cabins and high brick blocks. There is every where a sign of haste and uncertainty. No trees are to be seen; the stets take a bold plunge from heights above to the levels below. There is nothing soft or winning to the side which nature shows. By some great convulsion the hills have been created, and man has occupied them with all their crudities.

Silver Bow County, of which Butte is the country-seat, has the smallest superficial area, but the largest population, of any country in Montana. It was originally a part of Deer Lodge County, but in 1881 achieved its independence by reason of the discovery of the great copper and silver leads at Butte and vicinity. Mining is the main industry in the country, which so early as 1870 contained the locations of 981 gulch claims and 226 bar and hill claims. The total cost of ditches at that time was $106,000. Gulch mining prospered until 1871, when it collapsed.

Butte is the centre of what is known as the Summit Mountain District, and has an elevation of 5800 feet. The city is virtually the county of Silver Bow. Under the general title of Butte are included Butte proper, South Butte, Walkerville, Centreville, and Meadesville; the several towns from the largest and richest mining camp in the world. The district of which Butte is the natural centre is three miles square, and contains more than 5000 mineral claims, 2000 of which are held under United states Patents. The product of the camp for 1886 was $13,246,500, divided as follows:

Fine bullion per express................................ $5,856,500

Copper (55,000,000 pounds, at 10 cents) $5,500,000

Silver ore shipments........................................ $650,000

Silver in matte................................................... $1,240,000

Total.............................. $13,246,500

In 1881 the output amounted to only $1,247,600. For 1887 the returns show na increase over the product of 1886 of over $3,000,000. Nearly 5000 men are employed in the various stamp-mills and smelteries, and the monthly pay-roll amounts to $500,000.

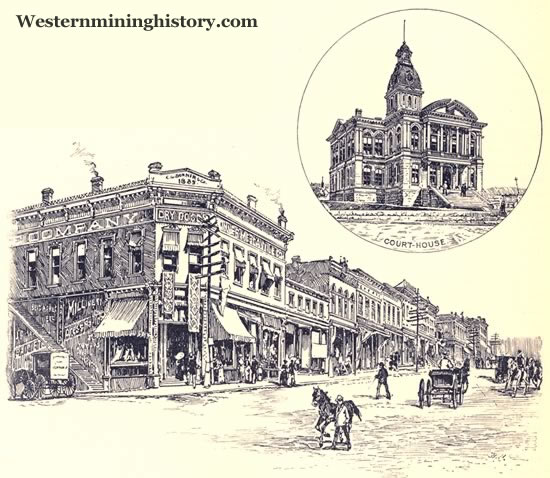

The post-office at Butte pays a net profit to the government of $23,000 a year. The city is well supplied with banks, carrying check deposits aggregating over $2,000,000, and has an assessed property valuation of from $8,000,000 to $9,000,000. On the business streets are a number of buildings of great size and solidity, and elsewhere are several private houses built by those who have made princely fortunes since coming to Butte. Particularly noticeable are the public buildings, such as the schools and Courthouse. The latter cost $150,000, and on the former more than $100,000 have been expended.

Gas and electricity are used in lighting; the retail trade is large; and as a rule Butte is a well-regulated city, enjoying a majority of the modern improvements, and happy in the knowledge that its fame is world wide, and its prestige as a mining centre undisputed.

Quartz locations were made on and near the present site of Butte as early as 1864. In 1867 the town site was laid out, and Butte had a populations of nearly 500 souls. The early comers were only moderately successful in their ventures, however, and in time the placer claims were exhausted.

In 1875 came the startling discovery that the "black ledges of Butte" were rich with silver. The news spread rapidly. Old claims were relocated, and smelteries and mills erected. The camp grew readily. In a year the Utah and Northern road reached the place, and the present era of wealth and progress was fully inaugurated. This, in brief, is the history of Butte. All its trails and disappointments came at an early day, and when once overcome, never returned.

Today the Utah and Northern furnishes its southern outlet, and the Montana, Union, and Northern Pacific its eastern and western. Before another year passes the Manitoba will give it still another direct connection with the outside world, and with other local lines will bring it into closer communication with Helena and the various districts of Montana.

The mines of Butte are of two classes-one silver, the other copper-bearing. The silver ores vary in richness from fifteen to eighty ounces of silver per tone. Most of the silver veins also contain from $4 to $12 per ton gold. Some of the copper mines carry silver, but the percentage is small. The principal copper ores are copper glance, erubescite, and pyrites. The rough ore assays from 8 to 60 per cent copper, and most of it bears a concentration from two to two and one-half tons into one, with a small loss in lastings.

The process of mining as practiced at Butte is of too complicated a nature to be properly described by a layman, and I therefore quote from an expert. The silver ores, he says, are either free or base. In the first the silver contents are extracted after the ore has been stamped by simply mixing it with mercury in water, the precious metal amalgamating readily with the quicksilver.

In base ores, however, the process is more expensive and complex. After the ore had been hoisted from the mine, it is conveyed in handcars to the upper part of the mill, where it is put through large iron crushers, which reduce it to about the size of walnuts. From the crushers it drops to the drying floor, where all the moisture it contains is evaporated, and where it is mixed with proportion of salt varying from 8 to 10 per cent. of its weight, the amount of salt depending on the baseness of the ore. When thoroughly dried it is shoveled under the stamps-large perpendicular iron bars weighing 900 pounds-which are raised by machinery and permitted to drop on the ore below at the rate of about fifty strokes per minute.

The effect, of course, is to crush the ore to powder, in which condition it is taken automatically to the roasters. These are huge hollow cylinders, revolving slowly, and filled with flames of intense heat, conveyed from the furnaces below by means of a draught. As the cylinders revolve, the actions of the heat drives off the sulphur in the ore, liberated the chlorine in the salt, and a chemical change takes place in he nature of the silver in the ore, making a chloride of what was formerly a sulphide of silver, and rendering it susceptible of amalgamation with quick silver, just like the silver in the free ore mentioned.

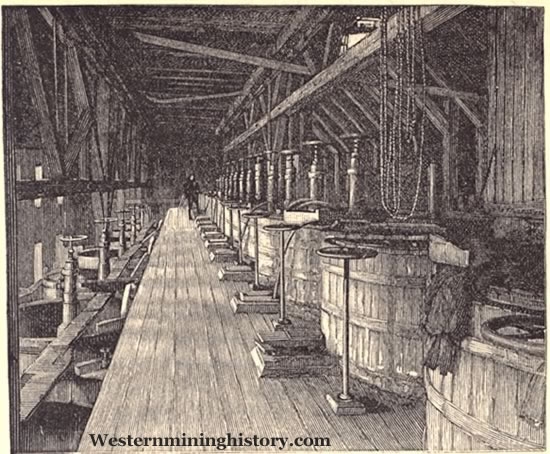

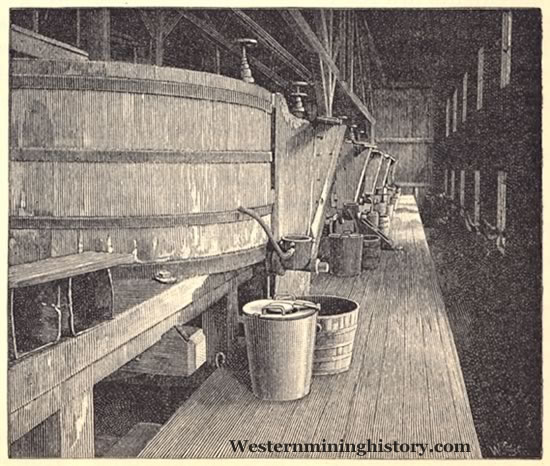

From the roasters the pulp is then conveyed by tramway to the pans-large tubes filled with water, in which quicksilver is placed with the pulp. The mass is then violently agitated, so that every particle of the sliver chloride comes in contact without eh quicksilver, by which it is taken up.

The whole is then conveyed to the settlers-another series of tubs in which the water settles, and from which the metal is drawn in eh form of amalgam. This is afterward subjected to heat, volatilizing the quicksilver, which is afterward condensed for use again by means of cold-water pipes, leaving the silver in a pure metallic state, to be melted into bars and shipped for coinage.

Copper ores are somewhat more simply smelted. They are of a sulphurous composition, and must be roasted before the metal contents are put in marketable shape. They are either desulphurized by heat roasting, or by being run through reverberatory furnaces. After this initial treatment, the ore, previously crushed and rolled to the fineness of sand, is dumped into the matting furnaces, whence, so far as possible, the worthless ingredients are reduced to a molten state to separate them from the metal base. The metal is then drawn off into sand cavities, similar to the drawing off of pig-iron, where the metal cools and becomes copper matte, this matte usually assays from 55 to 65 per cent. of copper, besides the silver it contains. Silver copper matte is a desirable matte.

The Parrott Company, by an adaptation of the Bessemer converter process, produces a copper matte carrying only two per cent. of impurities. The process is a very interesting one, and probably the cheapest in use in this camp, all things considered. Some of the Butte companies, whose ore carries form 49 to 79 per cent. of copper, ship their product in a crude state-some to Eastern smelters, others to England and Wales. The high per cent. of copper returns a handsome profit.

Our hotel at butte was nearly the centre of the city. Close by ran the main street, with its ever-changing pictures, and from the upper end of which we could look down upon the famous camp. The sight was novel in the extreme. On every hand were tall smoke-stacks pouring forth smoke and flames like miniature volcanoes, and great heaps of mineral refuse were scattered around promiscuously. There was nothing to see but stamp-mills and smelteries, nothing to do but visit them. Mines and mining were the talk of the hour. No one thought of anything else.

The very ground seemed honey-combed, and we know that by day and night an army of men was at work in the dimly lighted cross-cuts, industriously searching for the treasures nature so long refuse to disclose. Rough looking, pale, worn, and haggard are these miners of Butte. Many of the them have lived the greater part of their lives in the horrible chambers that, lined as they are with precious metals, have still no charm for their inmates. Life in the mines is modern slavery. The looks of the men prove this; the wan faces of the childern bear painful evidence of the fact.

Above the city proper, on the road to Walkerville, were grouped the cabins of these laborers. Nothing more desolate than their appearence can be imagined. Perched on rocky ledges, crowded into narrow gulches, unpainted, blacked by the smoke, unrelieved by tree or shrub or grass-plot, they bore not even the suggestion of home, but were more like hovels-untidy, neglected, and oppressive to look upon.

There are 340 stamps in operation at Butte, and the amount of ore treated every day amounts to 500 tons, ore 15,000 tons per month. Besides the stamp-mills there are seven smelteries, with a capacity of 1250 tons.

A majority of the mines have their own mills and smelteries, equipped with every modern appliance for the rapid and saving reductions of ore, and all are rich producers. Viewing the many properties, acquainted with their figures, one wonders how copper can be cornered, and how long it will be before silver is a drug upon the market.

Related Articles

Two Montana Cities Part I - Helena

Butte, Montana information and photos