By Gary Carter

Author’s Note

I began my interest and research in the history of the Vulture Mine in 2011. Until recently the story of the 1880 pipeline was just a small chapter in the overall history. For more than a year, Frank Brailo, of Surprise, Az., has had a passion, commitment, and eagerness to investigate, find and ponder the story of the old pipeline.

He is the “Dean of the Vulture Pipeline” and has undoubtedly drove more back sandy roads, driven over the dry Hassayampa, met up with more cactus bushes and cholla than anyone else in search of not only pieces of the steel pipe but its route, and story.

Frank’s enthusiasm is contagious and my trips with him have been memorable. Along the way he has been able to establish, from pipe remains, maps, metal detectors and good old fashioned detective work and incessant scouting of the miles between the Seymour site and the Vulture Mine numerous sections of intact pipe and what appears to be metal patches to shore up leaks. All the pictures associated with this story were taken and belong to Frank Brailo.

Introduction

By the mid 1870’s the first big gold mine in Arizona, The Vulture, had begun to stumble. Rich ore was still being encountered but quarrying, high wood, water, and transportation costs necessitated that only ore of $25 per ton be hauled to the river mills, some 13-15 miles away.

Steam was the power mode and for that the two crucial ingredients were wood and water. Despite efforts, no water source was found at the mine site, and the scarcity of wood in the surrounding desert often necessitated closing the mills above Wickenburg and arrastras for indeterminate periods of time. Wood was $8 a cord and the mills, when under full steam, were using over 30 cords a month.

From 1866 to 1879 mill sites were moved several times to access a new wood supply from scant desert vegetation. Every bit of water for domestic and mining needs was transported in 40 large barrels, by wagons to the mine site at a cost of $10 a wagon load.

Claim disputes and litigation, a deepening depression, and the expense of driving shafts contributed to the narrow profit margins for the Vulture Mining Company (VMC), however, at the same time and until 1878, P.W. “Bill” Smith and Company were mining Vulture ore from their nearby extension claim, hauling it to the Smith Mill down stream on the Hassayampa and doing quite well. This served to convince many that poor management by the VMC may have been the root cause of their problems.

By 1872 various mining men had envisioned several ideas to reduce the costs of hauling ore, water, and wood. The two ideas most considered were to build a narrow gauge railroad or to build a pipeline from the Hassayampa River to the mine site. The Hassayampa, which comes through Wickenburg and is about 13-15 miles from the mine site, is dry along large stretches and shallow wells would need drilling to supply water.

From 1873-1878 the Vulture Mining Company was down as much as it was operating. During 78 and 79, James Cusenbary and James Seymour, representing Eastern capitalists began buying out all the Vulture claims, including the Smith property. The new group was named the Central Arizona Mining Company (CAMC).

Exploratory work and development were done to outline potential ore reserves and a prospectus was printed. Stock sold well at $10 a Share. Seymour was an inveterate promoter and promised to bring the Vulture back to its past glory. As such he made plans for a new town, to be called Seymour, on the Hassayampa, not far from Smith’s old mill. In fact, water for domestic use in Seymour came from Smith’s old flume.

Twenty of the stamps from the old mill above Wickenburg were moved to Seymour and a well was dug into the dry river bed to provide water. Lumber for the new 94’ x 60‘ mill building was transported from Prescott by the famous Cerro Gordo Freight line. Additional stamps for the mill were ordered and from April through July of 1879 continual deliveries of equipment and other needed items were hauled from railroad stops at Gila Bend and Maricopa to Seymour.

Excitement and anticipation were promoted in the Weekly Arizona Miner( out of Prescott) and soon lots were sold. Saloons, a mercantile store, boarding house, corrals and stables, a stage stop began construction. One saloon advertised a Billiard Table. In June of 1879, Isaac Levy came from Wickenburg to open a Post Office

Incredible as it may seem as early as February of 1880 Treadwell was seeking a surveyor to determine a route for a potential pipeline to carry water to the mine site. By May more and more news leaked out about that possibility. Of course, the realty of this would mean water delivered to the Vulture Mine, a mill built there and overhead costs of hauling ore, water, and labor needs would be drastically reduced—and the end of the need for Seymour!

The Vulture mill at Seymour did begin processing ore in the summer of 1879 and while the haul to the river was somewhat shorter than going to the mills near Wickenburg, it soon became apparent that another solution was needed if the abundance of 2nd grade ore from the mine was to be worked profitably.

The Pipeline

CAMC Superintendents Shipman and George Treadwell were insistent and convinced the Sexton/Cusenbary group that a pipeline from the river to the mine was the solution to lowering costs and increasing profits. Treadwell was an excellent mining man and noted for increasing the efficiency of mill operations.

The pipeline proved to be more than just an idea when in April of 1880 a contract was signed with the C&M company of New York to manufacture 14.5 miles of pipe and also to make some parts for a new stamp mill. (it is often erroneously reported that the pipe was made and riveted in the Vulture blacksmith shop.) It is unclear when the pipe sections arrived but news reports indicate that 30 men were employed to work on laying the line.

After completion the CAMC employed a crew of 4-5 men (called “Water Service”) hired exclusively to keep the pipeline in repair and operating. By November of 1880 water was flowing (eventually at full flow of 400,000 gallons a day) through the pipeline some 13-15 miles (mileage accounts vary) from the Hassayampa River wells near Seymour to the mine site.

Steam was used to provide pumping power in some places but a 320 foot rise was the highest that water needed to be pushed. From that height it flowed mainly by gravity over a relatively flat desert surface to a reservoir near the mine and new mill site.

The Central Arizona Mining Company apparently was so certain of the project and the potential of the Vulture that company reportedly spent around $380.000, with close to $30,000 of that for pipeline. William Phipps Blake, a mining consultant of some renown arrived at the mine in 1879-80, and Cusenbary told him the cost was $2100 per mile but that the initial outlay of capitol would be quickly recouped by the reduction in expenses.

There is a scarcity of information as to the construction of and needs of workers who laid the pipeline. The following accounts of pipeline construction are assumptions made by the author from old newspapers, and much historical research.

Water pipes of seven-nine inch diameter steel with different gauges and thirty inches in length were manufactured with rivets and in straight sections. Slip joints were used to connect portions. Incredibly all of the pipe was straight with no elbow bends. Much of it but not all was buried to a depth of about 12”. In areas where it was necessary to bridge the many desert washes, rock trestles were built to carry the pipe from one side to the next.

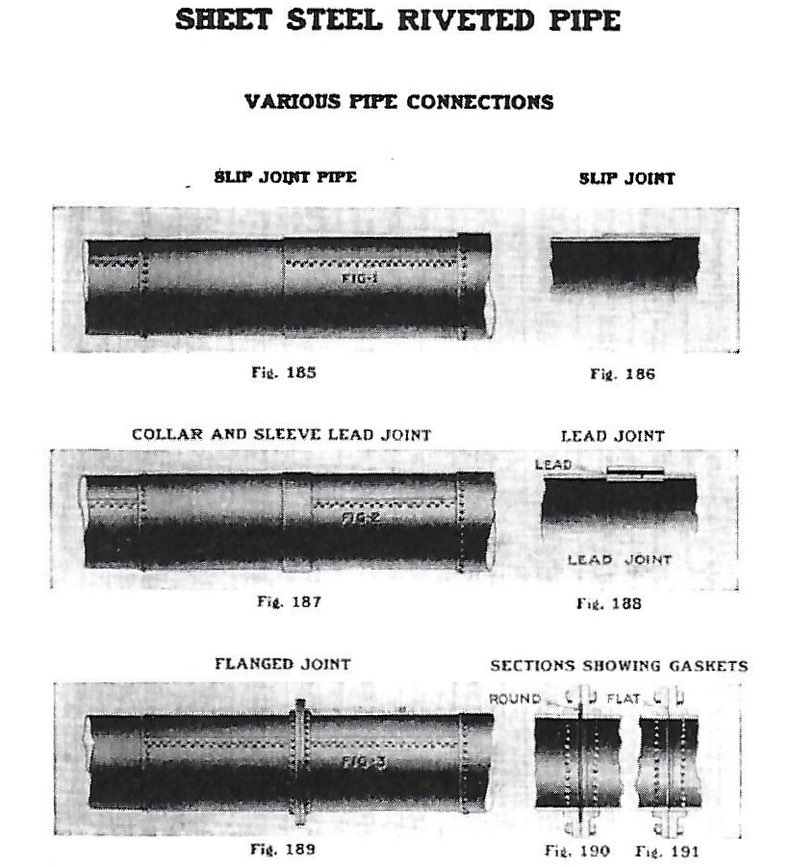

Sheet steel riveted pipe is now largely used for conducting water considerable distances for power purposes.

The pipe is made up by rolling light sheet steel plates into cylindrical form and riveting them together as shown. The sections are usually made in lengths of 20 feet for convenience in transportation, but if the occasion demands they may be made as short as 5 feet. The various styles of joints employed are clearly illustrated, the pressure involved determining which is best adapted.

The connection most commonly used is the “slip joint” shown in Figures 185-186. This is extremely simple and may be likened to the old-fashioned stovepipe connection, being put together without skilled labor. The joint is made by having one end of each section slightly tapered, slipping one section in to the other and driving it tight. A perfectly safe joint is thus made, which is good for heads up to 400 ft.

Parties are urged to submit full details of their proposition, together with a profile or sketch of the pipe line if possible, as this will enable the Company to calculate accurately the size of the pipe required, and to economically distribute the various thicknesses of pipe according to the pressure involved in the line.

The pipe was made in New York (why not SF?) and shipped by rail to either the station at Gila Bend or Maricopa (Wells). Each one had a trail/wagon road that came to Seymour the origin of the pipeline. Pipe needed to be off loaded from the train, reloaded on freight wagons and hauled overland to the work sites. It is not known if the pipes arrived in one very large shipment or were delivered over a period of time. In any event both railroad stations are around 75 miles from Seymour and innumerable trips and freight wagons would have been needed.

Crews of men would dig trenches, build rock trestles where needed, lay pipe, and cover it over. The pipes were coated with a thin layer of tar for protection. t is not known if that was applied in the field or at the factory. A surveyor and assistant would undoubtably have been along with the work gang. Even now dirt roads in this area of desert are ungraded, uneven, and rocky. Loaded freight wagon would have had a chore.

As the work progressed food and supplies were either brought to workers each day or more likely food, supplies and movable tents and camp spots set up. Further putting the project and men to test was the fact that the pipeline was not finished and operating until Nov. of 1880, and while the exact start date is not known the bulk of the work was done during the hot summer months.

Eventually, despite the initial capital expenditure, the project proved to be a financial success for the Central Arizona Mining Company and between 1880 and 84 they took out over $2 million until a reduction in ore grade and a major fault cut off the lode. The CAMC began a slow downturn after 1884 and eventually leased the property which was later bought by Lyman Elmore and then in 1887 by the famed Colorado Silver King, Horace Tabor.

The laying of the line to the mine was more than just a construction and engineering success. The ability of the Vulture Mine to be profitable provided all of Central Arizona with the means to begin to develop and flourish. In 1880, Phoenix had a population of less than 2,500, and the railroad did not reach into the southern areas of Phoenix until 1887.

An early report in the Arizona Republic sums up the importance of the Vultures operation to the area. March 14,1901-“ It has been a big mine, and when I first came here all of the money we could see was from Vulture gold.” Another—“if it were not for the Vulture Mine, Phoenix would not be what it is today, it was a big feeder for the town and many people and businesses would not have been successful if not for the Vulture Mine.”

Of course, Wickenburg’s fortunes and population rose and fell with the Vultures success or failure. At the mine site it was not until the pipeline and the mill operated there (1880) that the term Vulture City began to be used. Prior to this mail was addressed to “Vulture”. Instead of just hard scrabble miners living in bunk houses, families and businesses began to come and the area became known as Vulture City (actually this was the 2nd Vulture City as the first was the area that built up around the early mill sites, near Wickenburg, on the Hassayampa.)

The end for the pipeline was quick, and final. In 1890, the Walnut Grove Dam built on the upper reaches of the river failed and sent what is described as a 40’ wall of water down river, through Wickenburg, Smiths Mill and the Seymour area. Exact number of deaths are estimated between 70 and 100. Most of the homes, farms and buildings along the river were swept away.

About 5 miles of the pipeline near Seymour and inland were destroyed and because of costs never rebuilt. After 1888, the Vulture was often idle and in disrepair, or being worked by small time lease operators. Water was found at the 300 level of the mine and was sufficient for the small amount of milling that was done.

Vulture City rapidly declined and it was not until 1908 when a new company took over, did exploratory and development work, drilled a successful well that the mine entered its last real productive time of underground mining.

Related: Vulture Mine – History, Fact, and Fiction