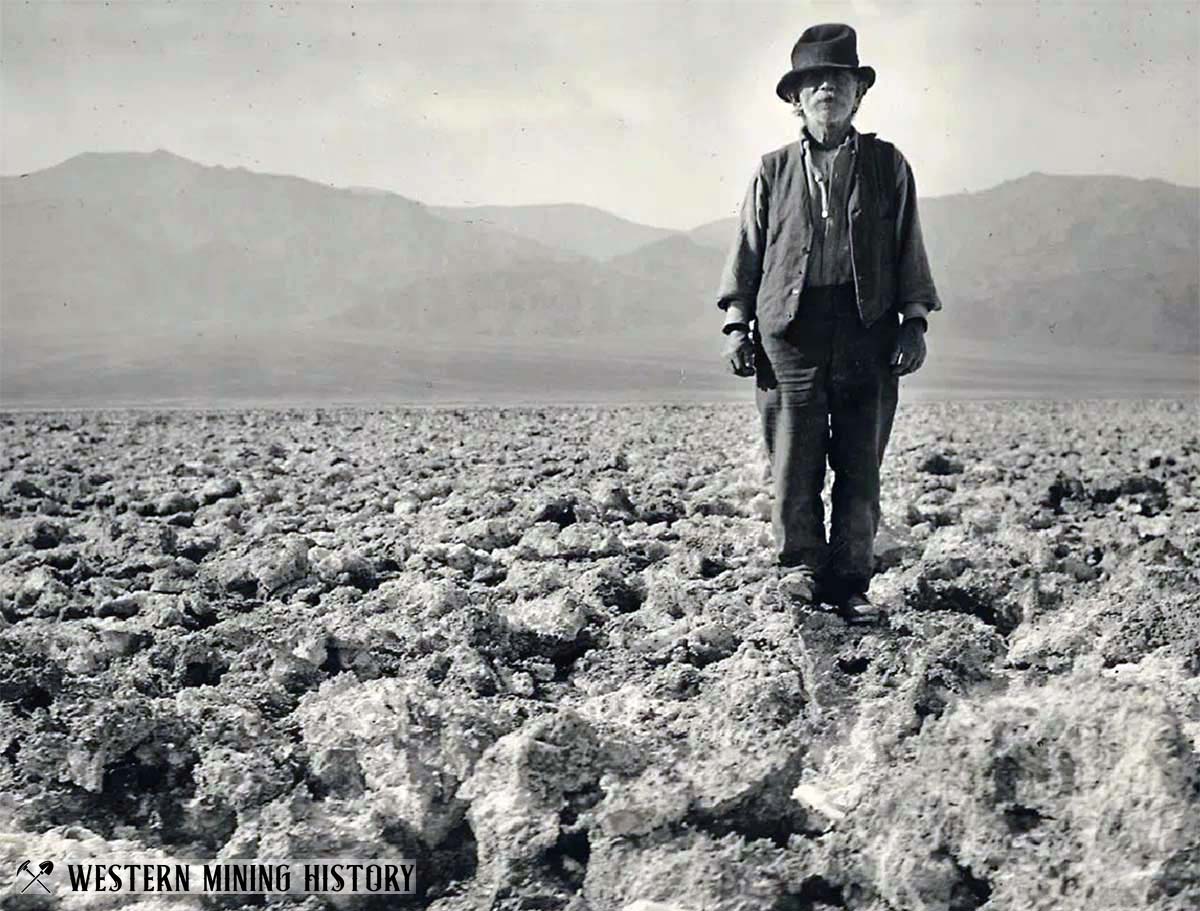

Frank “Shorty” Harris is one of the West’s most famous prospectors. There have been many notable prospectors that have made bigger strikes than Harris over the years, so what is it about him that has captured so much attention?

According to the Death Valley National Park Service “Shorty Harris was one of the greatest, and most colorful, of the old time prospectors. Shorty was responsible for some of the region’s most famous gold strikes and most famous gold rushes.”

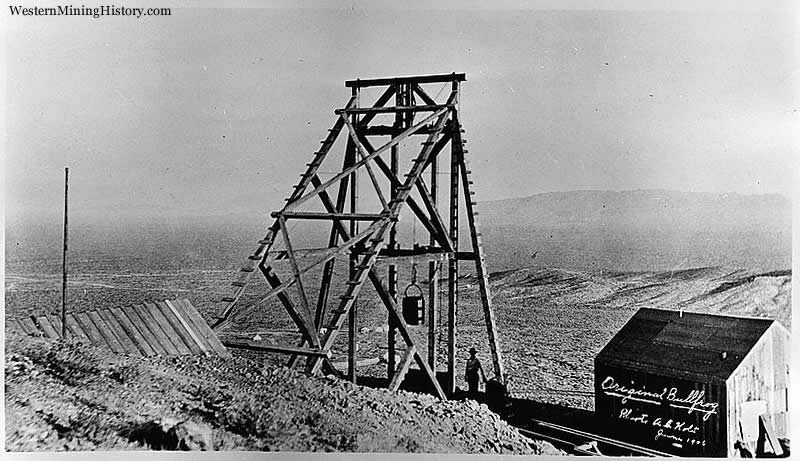

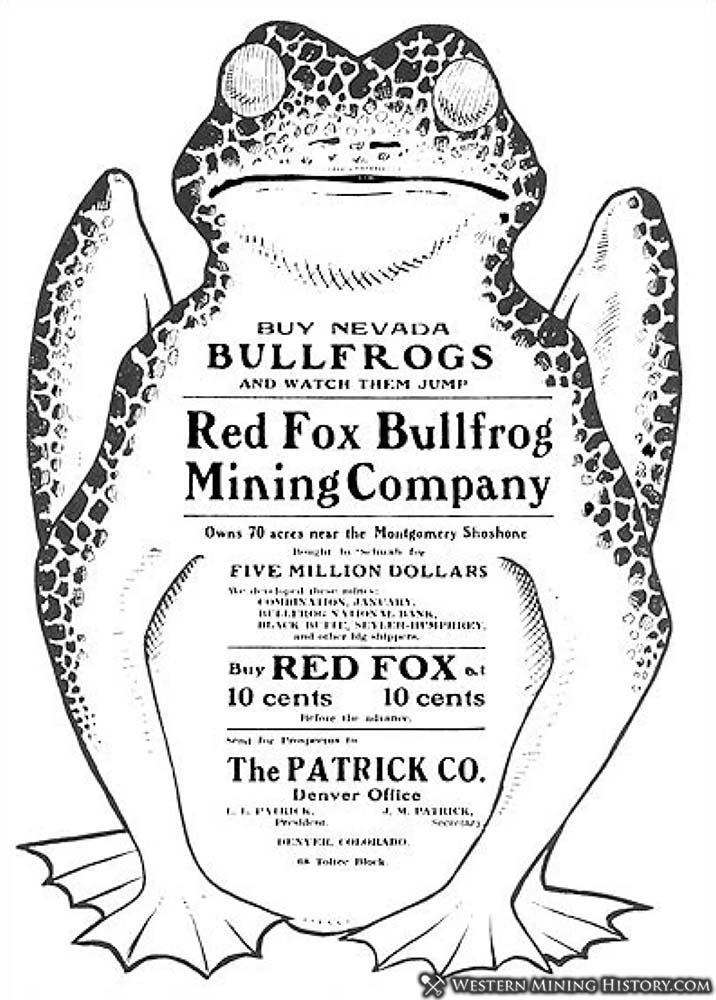

Shorty’s primary source of fame was his 1904 discovery of the Bullfrog claim that resulted in the frenzied rush to Rhyolite in Nevada ( a detailed account of this discovery is included below). That discovery made him famous, and in subsequent years anything notable that he did ended up getting mentioned in newspapers throughout the Southwest and California where he became a bit of a legend.

What also made him noteworthy is that he never gave up the life of a prospector, and lived most of days in California’s Death Valley region. He was one of Ballarat‘s last residents, living his latter years in a crude adobe building–a simple life that many found interesting even well after his death in 1934.

Who Was Shorty Harris?

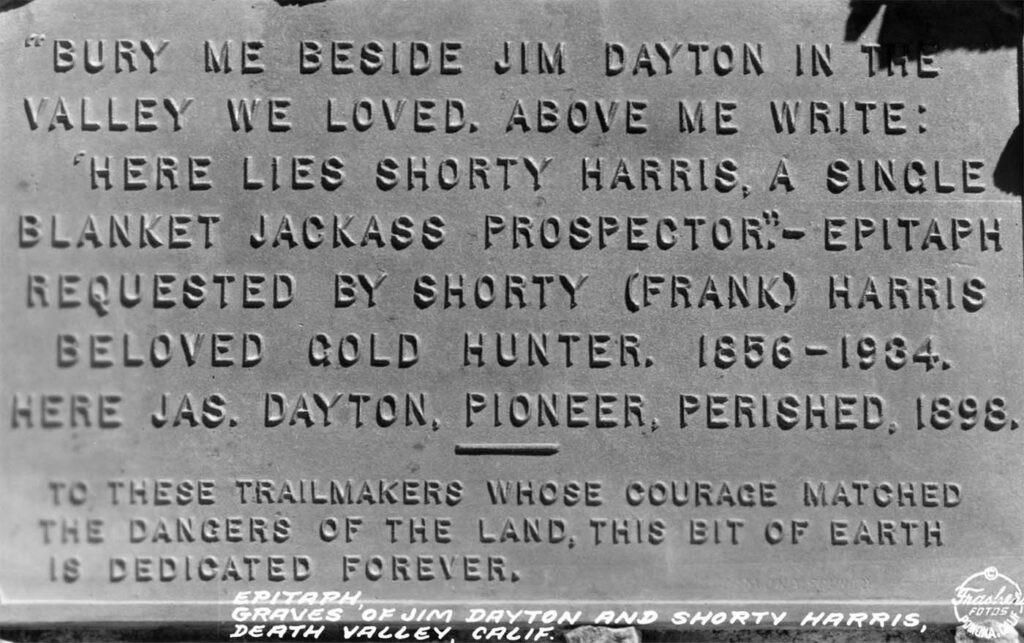

The most concise answer to this question comes from Shorty himself: “A single-blanket jackass prospector,” which were the words he requested be put on his grave marker. He is described as a man short in stature, always wearing clothes several sizes too big. He was popular in the region and was known for always helping someone in need.

He was also known for his love of whiskey, admitting that most of his lost wealth was the result excessive drinking.

In 1931 Shorty spent a some time in a Los Angeles hospital for unknown reasons, and while he was there he was interviewed for a front-page article in the Los Angeles Record, in which he tells the story of his life and lists some of the notable places he lived while wandering the West as a prospector. The following are excerpts from that interview:

‘Shorty’ came out of New England to California 54 years ago. He was an orphan boy who had run away from home and deadly drudgery in a calico mill. Perhaps he heard of Horace Greeley’s profound advice, for he went west.

As the years passed he became one of the most colorful figures of the old frontier. He prospected from Coeur d’Alene to Leadville and on to Ballarat.

He made fabulous strikes, including the spot where the famous Bullfrog mine was later located and where the ghost town of Rhyolite grew and flourished and died away.

Fortunes in magic yellow gold came his way and slipped through his fingers after the easy manner of the old west.

Shorty Harris lived on the plains and in the mountains during the fabled days when a barking sixgun and a lynching rope were the only law.

He also talks about spending time in Tombstone in 1885, describing it as “almost as hell-roaring a place as Leadville. The boys were all decorated with six-guns and believe me, they knew how to use them. The handiest on the draw stayed in town, but those that were too slow made a one-way trip to Boot-Hill”

Later in the interview Shorty is quoted as saying “While things were going strong I made several fortunes—and spent ’em all. The interest from all that money, if I had it now, would put me up with some of the big fellows in the city; but I’m a lot happier out there in the desert, where I’ve always lived.”

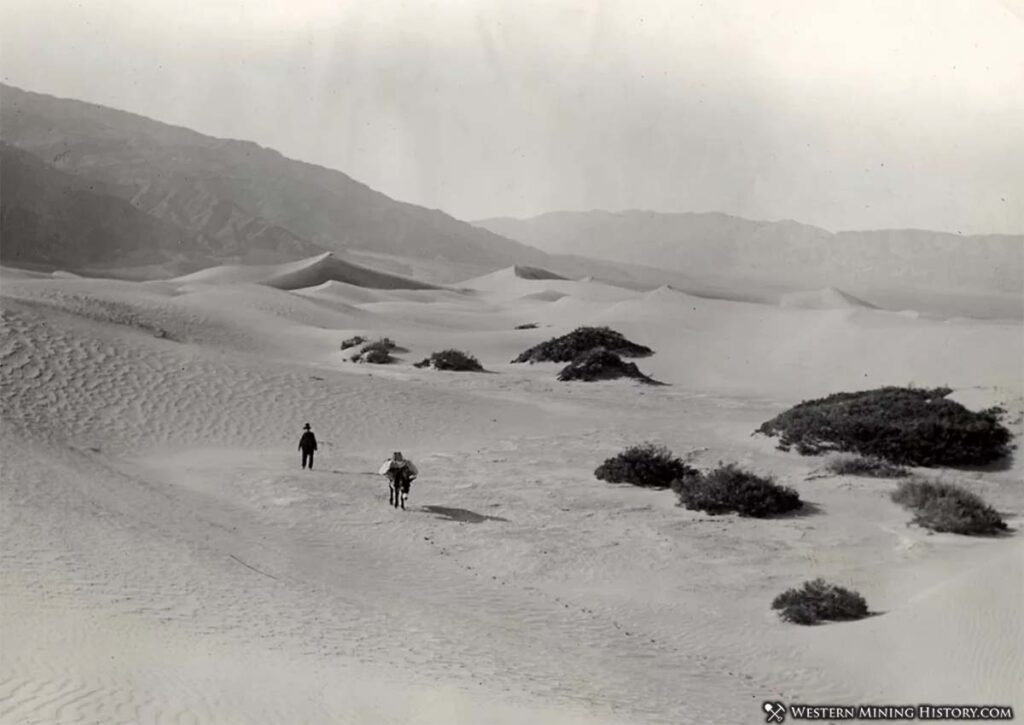

Death Valley Was a Dangerous Place for Prospectors

Death Valley is a region of extremes–some of the hottest temperatures on earth at low elevations and snowy peaks at higher elevations. Water is always scarce, and many prospectors found themselves in serious trouble while traveling in the area.

Shorty encountered as many dead or dying men while prospecting as he did valuable mineral deposits. Two of the more notable incidents are described below.

The July 2, 1905 edition of the San Francisco Call reported that Harris discovered two dead miners, and two more that had “lost their minds”. The article stated:

Shorty Harris, the discoverer of the original Bullfrog mines, came upon the dead men and the two crazy prospectors while going across the desert. He was attracted to the spot where the dead bodies were found by the yelping of a number of coyotes engaged in eating the flesh from the bones of the dead prospectors.

Harris states that the dead men undoubtedly were murdered, as he found a canteen of water on a burro near the scene of the discovery, thus proving that the men did not die of thirst.

The demented men were wandering on the desert a few miles from the dead men and were in a nude condition. Their tongues were swollen with thirst and they were unable to speak. They were taken into Bull Frog, where they are being cared for, but they are not expected to live.

Another incident involving Harris appeared in July 1907, when he encountered “a bunch of six miners who nearly met death from drinking wood alcohol.” According to press accounts, the men were in serious condition when Harris found them. He administered what aid he could and then summoned a physician from a nearby camp. The miners had mistaken the alcohol for a drinkable spirit and soon learned otherwise, narrowly escaping death as a result.

Shorty’s Fame Runs Short

Harris was a man of some renown following his Bullfrog discovery, and newspapers often reported on his adventures.

An August 1907 article reported that Harris spent several months prospecting in northern Nevada and Oregon:

Frank Harris, the veteran prospector and locator of Bullfrog, returned to Goldfield yesterday after a three months’ prospecting trip in northern Nevada and Oregon. “I am going to stay in this part of the state hereafter,” he said at the Esmeralda. “I was out three months and I did hot make a single location. I was in Seven Troughs, Pactolus, Berlin, and many other places.

In May 1909, Harris was shot during a dispute with a Mexican man with whom he had been playing cards. Many newspapers reported that he had been fatally wounded, and at least one paper even declared him dead. One account stated, “Harris struck the Mexican in the face, knocking him down. The latter then secured a pistol from the rear of the saloon. Both men drew weapons at the same instant, the Mexican shooting first.”

No articles could be found that corrected the reports of his death, and very few mentions are made of Harris after this incident. It is likely he spent many months recovering, but for how long or where remains a mystery. A 1913 article reported that he made a significant tungsten discovery in the Death Valley region, but this appears to be the final recorded mention of any discoveries attributed to him as a prospector.

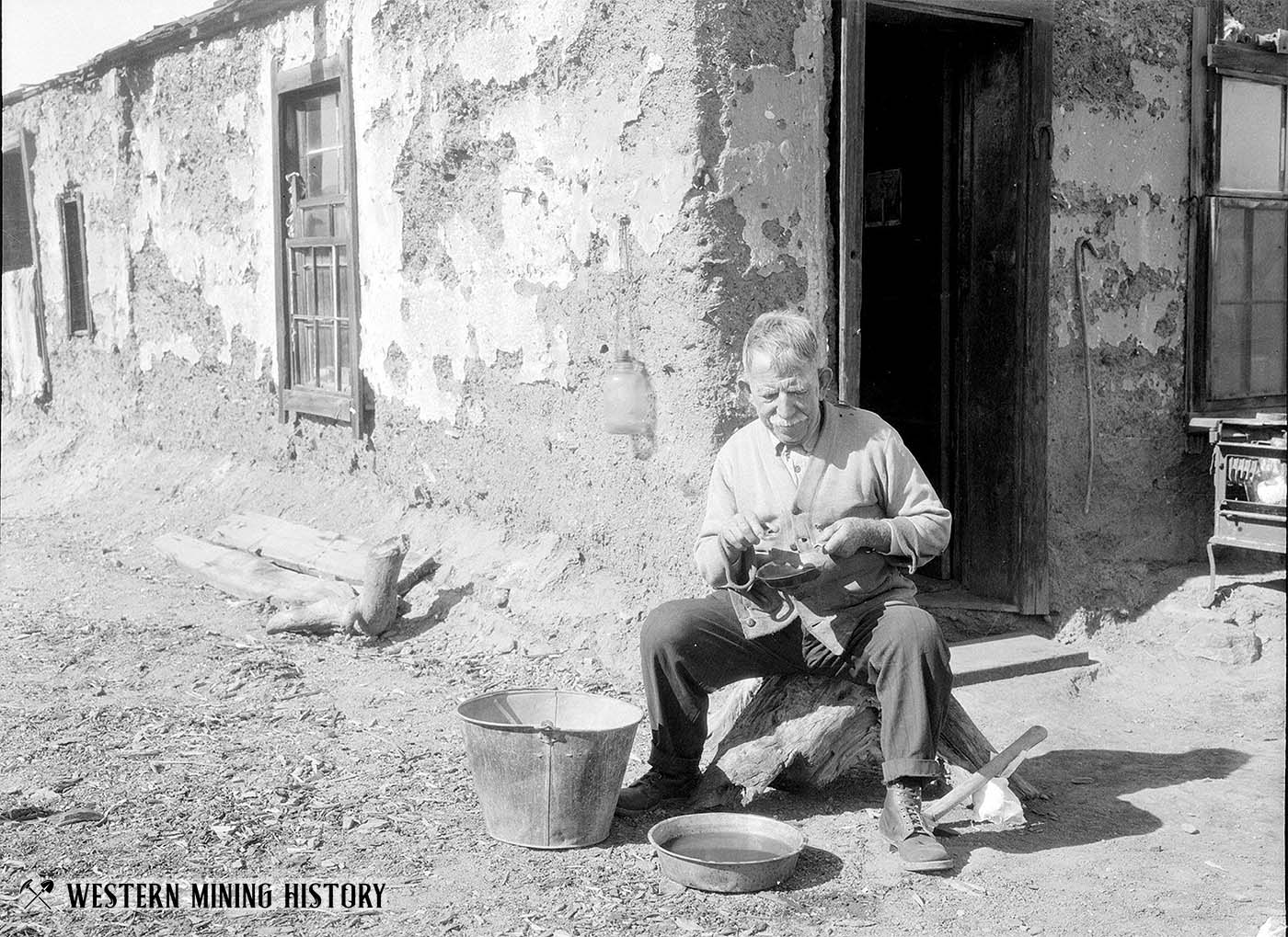

In the 1920s, Shorty toured the Death Valley region by automobile, revisiting many of the places he had frequented during his prospecting years, including the ruins of Rhyolite at the site of his famous Bullfrog discovery. He took photographs during the trip, one of which is shown above.

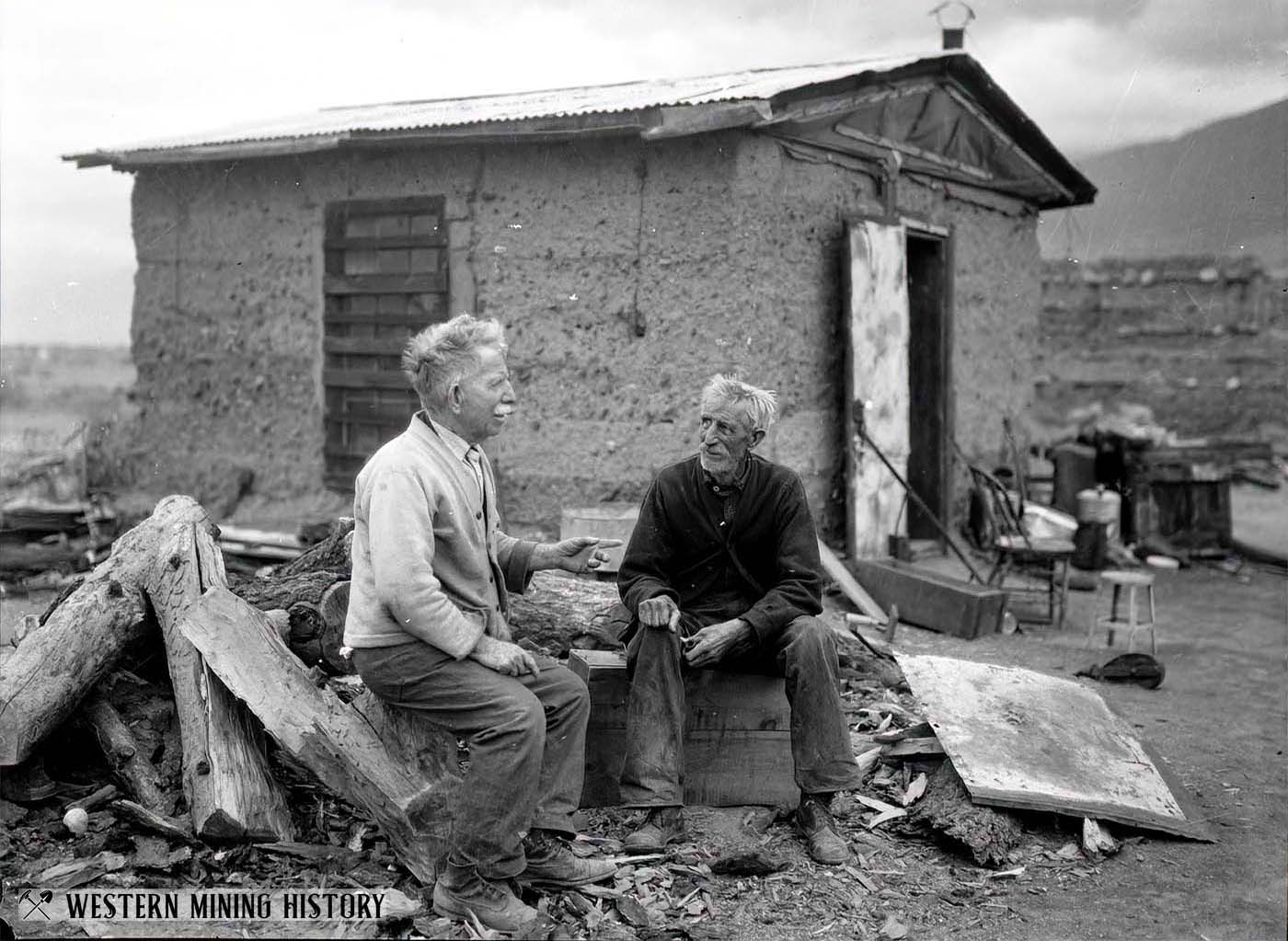

Starting around 1930, Harris, now in his 70s and still living in Ballarat, starting appearing in newspapers again. The public became interested in the story of this famous prospector as he neared the end of his life. Interviews from this period reveal many details of Shorty’s life that might have otherwise never been told.

In the 1931 Los Angeles Record article, Shorty remarked “I do some road work for the county, and earn enough to buy grub, and my rent doesn’t cost me a cent, because I live in the old schoolhouse and don’t have to pay any taxes. These old wheels of mine are pretty flat with rheumatism, but I’m still able to keep going and have a good time.”

An article from April, 1933 states that he was still living in Ballarat, which was “truly a ghost town, with only four or five persons, including “Shorty” Harris, famous mining man, living there now.”

Short spent his last months in the town of Lone Pine, and died in 1934 at the age of 78. At his request he was buried in Death Valley, next to the grave of his friend Jim Dayton.

Shorty and the Bullfrog Claim

The following text is from the October 1930 edition of the American Automobile Association of Southern California, and gives a first-hand account of Shorty’s discovery of the Bullfrog claim.

The best strike I ever made was in 1904 when I discovered the Rhyolite and Bullfrog district. I went into Boundary Canyon with five burros and plenty of grub, figuring to look over the country northeast from there. When I stopped at Keane Wonder Mine, Ed Cross was there waiting for his partner, Frank Howard, to bring some supplies from the inside. For some reason Howard had been delayed, and Cross was low on grub.

“Shorty,” he said, “I’m up against it, and the Lord knows when Howard will come back. How are the chances of going with you?”

“Sure, come right along,” I told him, “I’ve got enough to keep us eating for a couple of months.”

So we left the Keane Wonder, went through Boundary Canyon, and made camp at Buck Springs, five miles from a ranch on the Amargosa where a squaw man by the name of Monte Beatty lived. The next morning while Ed was cooking, I went after the burros. They were feeding on the side of a mountain near our camp, and about half a mile from the spring. I carried my pick, as all prospectors do, even when they are looking for their jacks—a man never knows just when he is going to locate pay-ore.

When I reached the burros, they were right on the spot where the Bullfrog mine was afterwards located. Two hundred feet away was a ledge of rock with some copper stains on it. I walked over and broke off a piece with my pick—and gosh, I couldn’t believe my own eyes. The chunks of gold were so big that I could see them at arm’s length—regular jewelry stone! In fact, a lot of that ore was sent to jewelers in this country and England, and they set it in rings, it was that pretty! Right then, it seemed to me that the whole mountain was gold.

I let out a yell, and Ed knew something had happened; so he came running up as fast as he could. When he got close enough to hear, I yelled again: “Ed we’ve got the world by the tail, or else we’re coppered!”

We broke off several more pieces, and they were like the first—just lousy with gold. The rock was green, almost like turquoise, spotted with big chunks of yellow metal, and looked a lot like the back of a frog. This gave us an idea for naming our claim, so we called it the Bullfrog. The formation had a good dip, too. It looked like a real fissure vein; the kind that goes deep and has lots of real stuff in it. We hunted over the mountain for more outcroppings, but there were no other like that one the burros led me to. We had tumbled into the cream pitcher on the first one—so why waste time looking for skimmed milk?

That night we built a hot fire with greasewood, and melted the gold out of the specimens. We wanted to see how much was copper, and how much was the real stuff. And when the pan got red hot, and the gold ran out and formed a button, we knew that our strike was a big one, and that we were rich.

“How many claims do you figure on staking out?” Ed asked me.

“One ought to be plenty,” I told him. “If there ain’t and I found a ledge of it southwest of Bill ain’t if I Shorty made it Beatty’s—but they had a hell of a time!

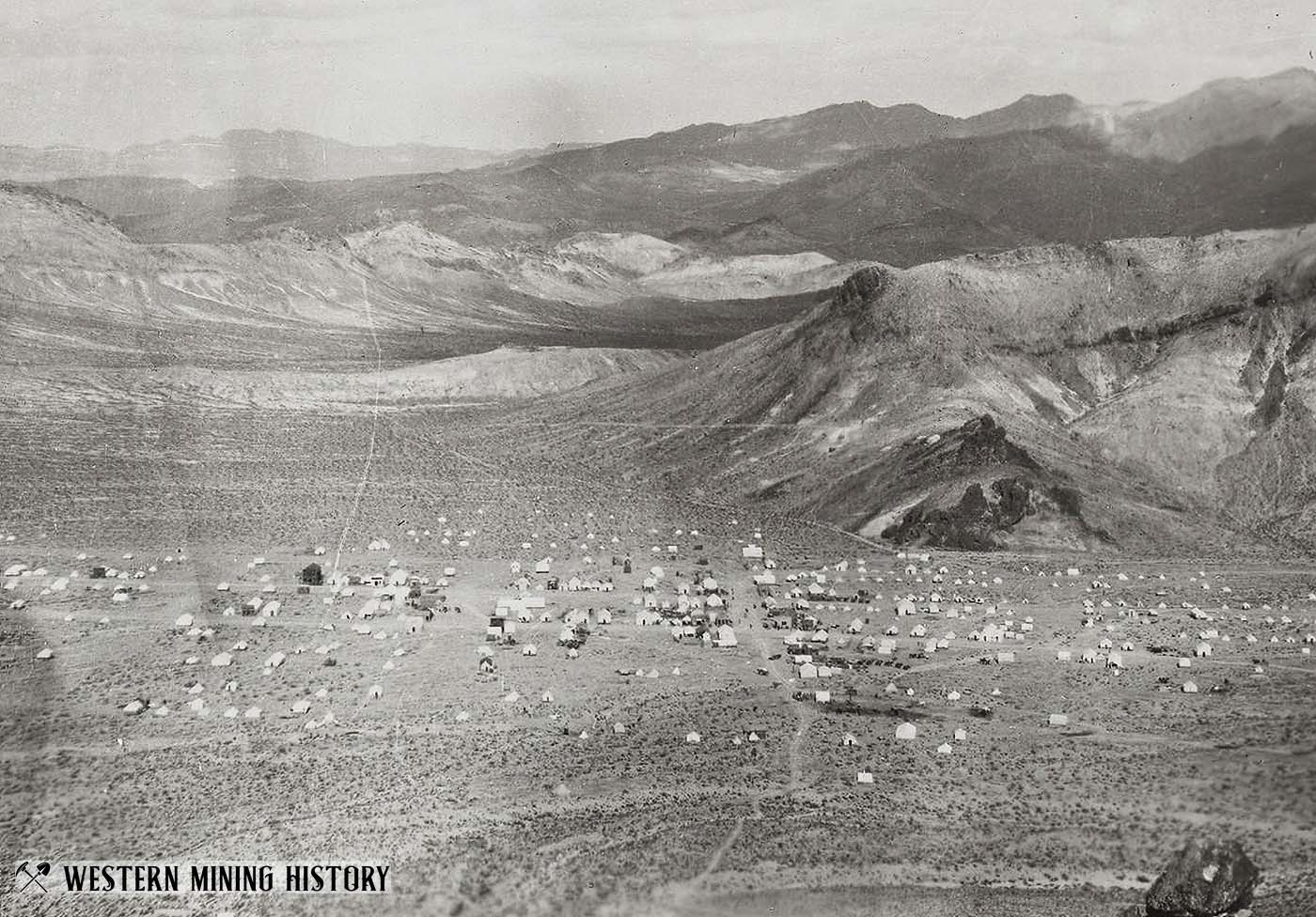

When Ed and I got back to our claim a week later, more than a thousand men were camped around it, and they were coming in every day. A few had tents, but most of ‘Shorty were in open camps. One man had brought a wagon load of whiskey, pitched a tent, and made a bar by laying a plank across two barrels. He was serving the liquor in tin cups, and doing a fine business.

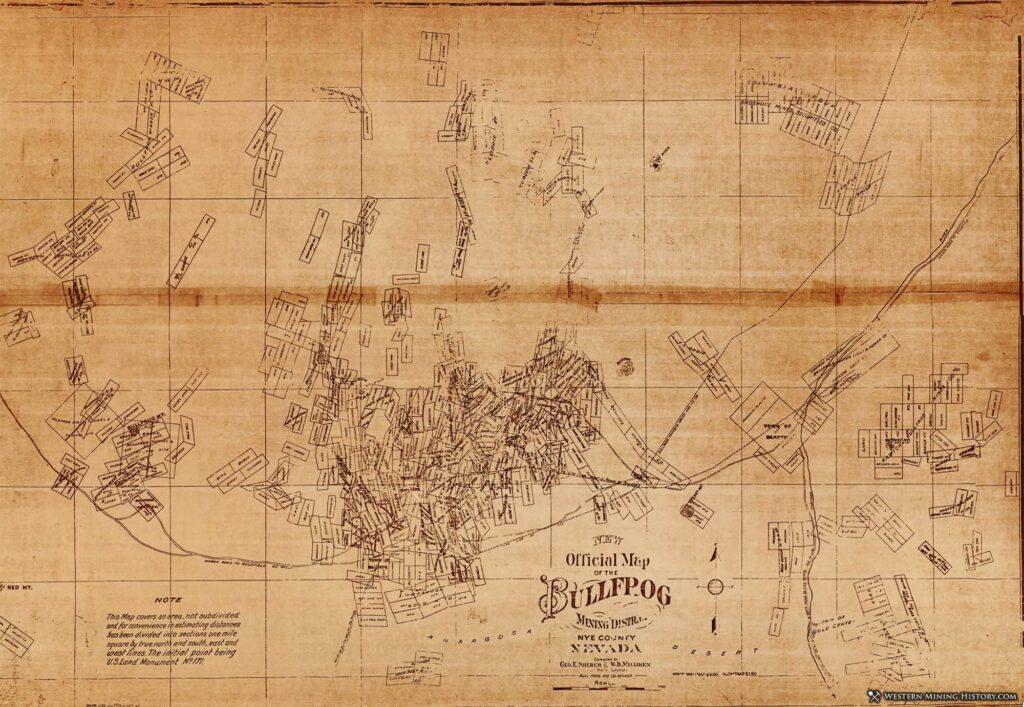

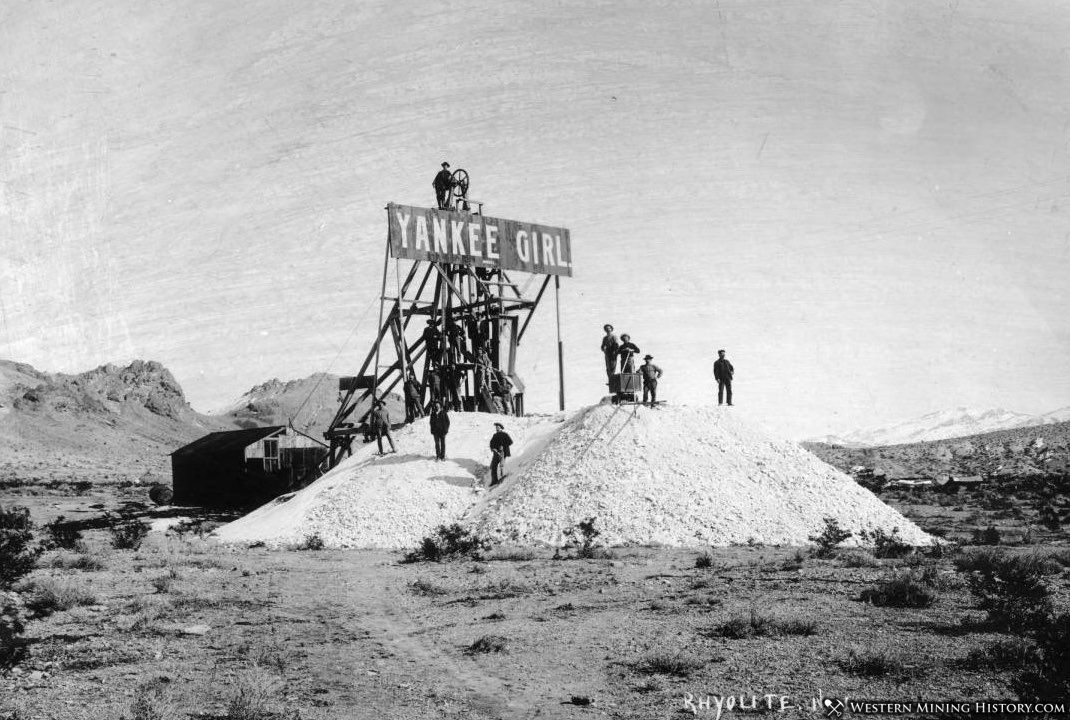

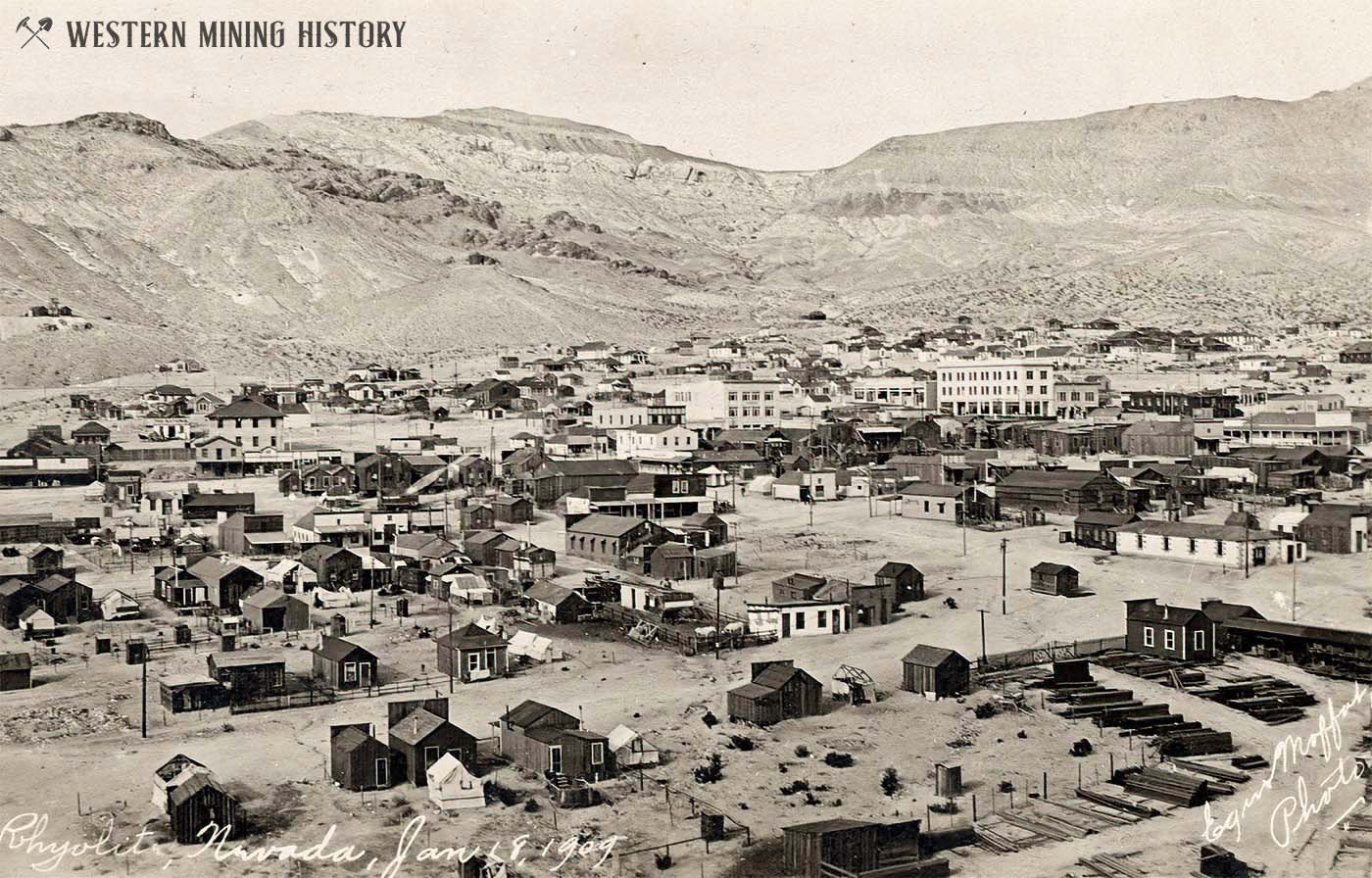

That was the start of Rhyolite, and from then on things moved so fast that it made even us ain’t dizzy. Men were swarming all over the mountains like ants, staking out claims, digging and blasting, and hurrying back to the county seat to record their holdings. There were extensions on all sides of our claim, and other claims covering the country in all directions.

In a few days, wagon loads of lumber began to arrive, and the first buildings were put up. These were called rag-houses because they were half boards and half canvas. But this building material was so expensive that lots of men made dugouts, which didn’t cost much more than plenty of sweat and blisters.

When the engineers and promoters began to come out, Ed and I got offers every day for our claim. But we just sat tight and watched the camp grow. We knew the price would go up after some of the others started to ship bullion. And as time went on, we saw that we were right. Frame shacks went up in the place of rag-houses and stores, saloons, and dance halls were being opened every day.

Bids for our property got better and better. The man who wanted to buy would treat with plenty of liquor before he talked business, and in that way, I got all I wanted to drink without spending a bean. Ed was wiser, though, and let the stuff alone—and it paid him to do it too, for when he did sell, he got much more for his half than I got for mine.

One night, when I was pretty well lit up, a man by the name of Bryan took me to his room and put me to bed. The next morning, when I woke up, I had a bad headache and wanted more liquor. Bryan had left several bottles of whiskey on a chair beside the bed, and locked the door. I helped myself, and went back to sleep. That was the start of the longest jag I ever went on; it lasted six days.

When I came to, Bryan showed me a bill of sale for the Bullfrog, and the price was only $25,000. I got plenty sore, but it didn’t do any good. There was my signature on the paper and beside it, the signatures of seven witnesses and the notary’s seal. And I felt a lot worse when I found out that Ed had been paid a hundred and twenty five thousand for his half, and had lit right out for Lone Pine, where he got married. Today he’s living in San Diego County, has a fine ranch, and is very well fixed.

As soon as I got the money, I went out for a good time. All the girls ate regularly while old em had the dough. As long as my stake lasted I could move and keep the band playing. And friends—I never knew I had so many! They’d jam a saloon to the doors, and every round of drinks cost me thirty or forty dollars.

I’d have gone clean through the pay in a few weeks if Dave alright hadn’t given me hell. Dave and I had been partners in Colorado and Utah, and I thought a great deal of him. Today he’s living over in em Canyon, and going blind. Well, I had seven or eight thousand left when Dave talked to me.

“Oldtimers,” he said “If you don’t cut this out you’ll be broke in a damn short time and won’t have the price of a meal ticket!” I saw that he was right, and jumped on the water wagon then and there—and I haven’t fallen off since.

Rhyolite grew like a mushroom. Gold Center was started four miles away, and Shorty. They decided to make the town the finest in Nevada—and they came mighty near doing it. Driscol built a three-story office building out of cut stone—it must have cost him fifty thousand. The bank building had three stories too, and the bank was finished with marble and bronze. There were plenty of other fine business houses, and a railroad station that would look mighty good in any city.

Money was easy to get and easy to spend in those days. The miners and Wildrose threw it right and left when they had it. Many a time I’ve seen ‘Shorty eating bacon and beans, and drinking champagne. Wages were just a sideline with them—most of their money was made in mining stock.

Rhyolite was a great town, and no mistake—as live as the Colorado camps were thirty years before, but not so bad. We had a few gunfights, and several tough characters got their light shot out, which didn’t make the rest of us sore. I saw some of those fights myself, but I never took any part in the fireworks. “alright, the foot racer” was what they called me because I always ducked around the corner when the bullets began to fly. I knew they were not meant for me; but I wasn’t taking any chances.

There was plenty of gold in those mountains when I discovered the original Bullfrog, and there’s plenty there yet. A lot of it was taken out while Rhyolite was going strong—$6,000,000 or $7,000,000—but they quit before they got the best of it. Stock speculation—that’s what killed Rhyolite!

The promoters got impatient. They figured that money could be made faster by getting gold from the pockets of suckers than by digging it out of the hills. And so, when the operators of the Montgomery-Shoshone had a little trouble; when they ran into water and struck a Overbury ore which is muckers, and has to be cut and roasted to be turned into money—the bottom dropped out of the stock market and the town busted wide open, She died quick, too. Most of the tin horns lit out for other parts, and that’s a sure sign a mining camp is going on the rocks.

If the right people ever got hold of Rhyolite they’ll make a killing; but they’ll have to be real hard rock miners, and not the kind that do their work only on paper. Rhyolite is dead now—dead as she was before I made the big strike. Those fine buildings are standing out there on the desert, with the coyotes and jackrabbits playing hide and seek around them.