Published in the 2016 Mining History Journal

By Larry Godwin

Click here to download the notes for this article

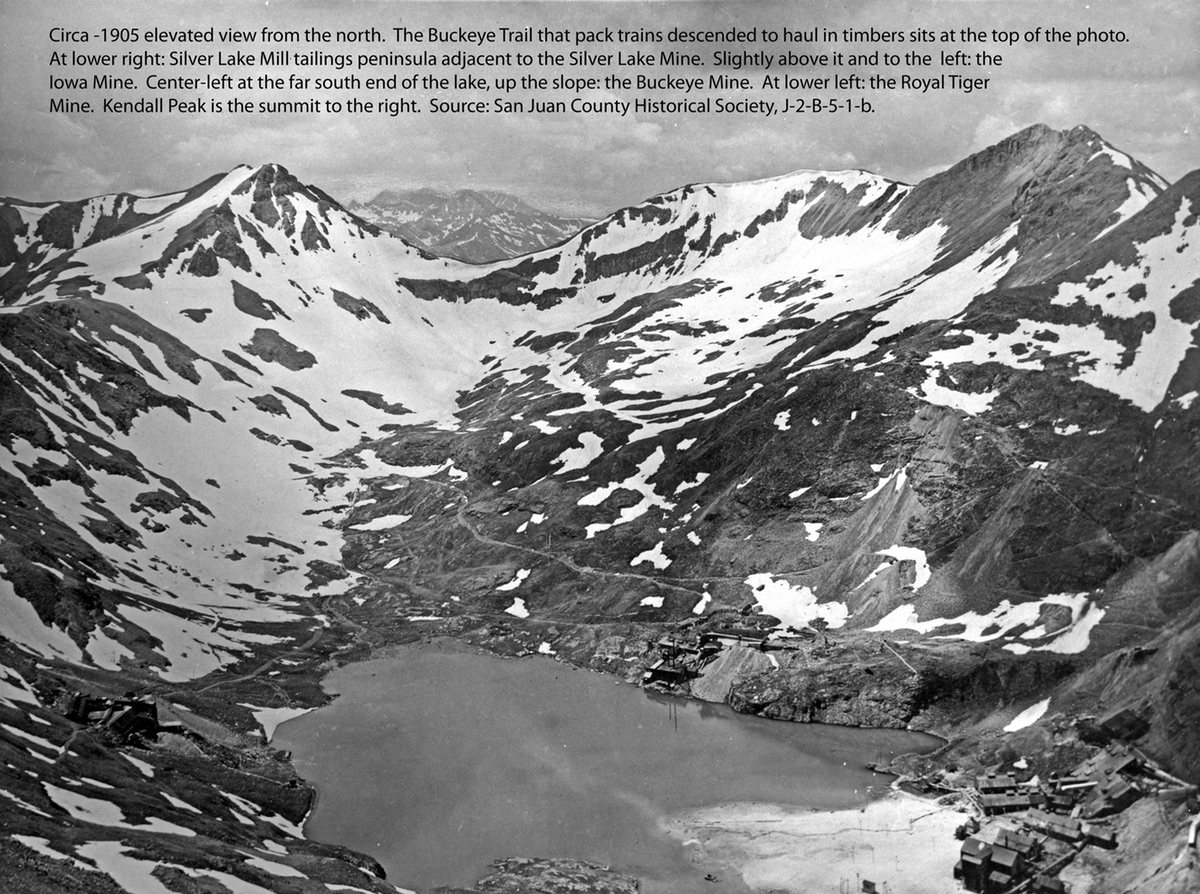

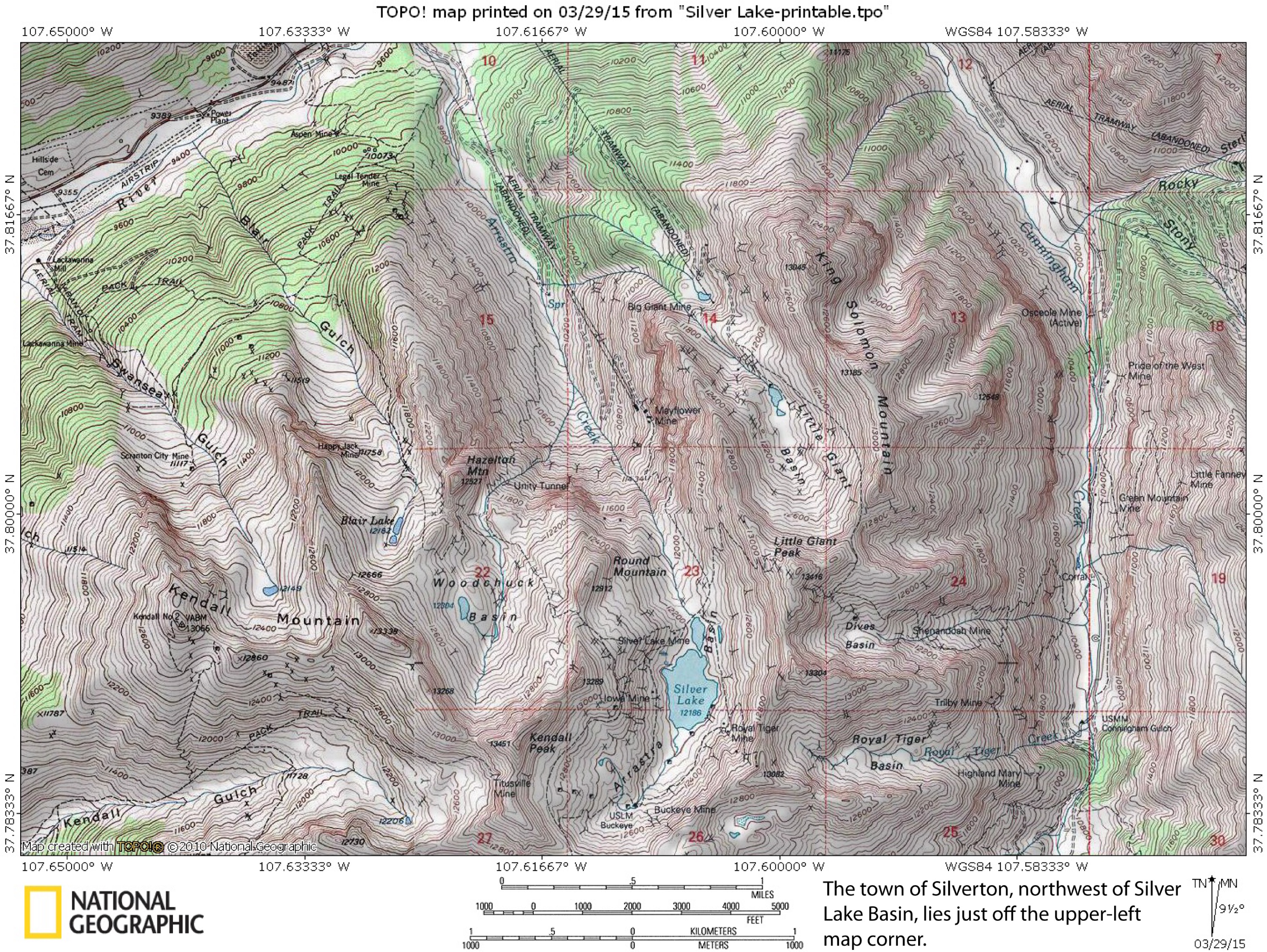

Silver Lake, which early settlers called Arrastra Lake, lies in a basin at the head of Arrastra Creek, four miles southeast of Silverton, Colorado, near the center of the Las Animas Mining District, in what was then part of La Plata County.

Early Prospecting and Mining

On June 15, 1871, prospectors created the Las Animas Mining District as a primitive form of frontier government to regulate claim activity throughout the vast Animas River drainage.1 During its first several years, explorers on the floor of Arrastra2 Gulch must have gazed up and south at the imposing headwall and wondered what lay beyond. Snow and ice locked in the precipice for all but a few months each year, discouraging exploration.

In 1875 a handful of independent explorers made the dangerous ascent into the upper reaches of Arrastra Basin. The following year, John Reed became the first documented prospector to scout a route up the headwall. On the other side, he found a hanging valley carved by glaciers, between North Star and other summits to the east and Kendall Peak and Round Mountain to the west. Their flanks, with 1,000 feet of relief, were sheer and rugged, and the mountaintops presented a lacework of veins and dykes. At the valley’s center lay what was at that time a pristine glacial lake, about 40 acres in size, surrounded on most sides by exposed bedrock,3 with its outflow cascading northward until it roared over the valley’s craggy headwall into Arrastra Gulch.4

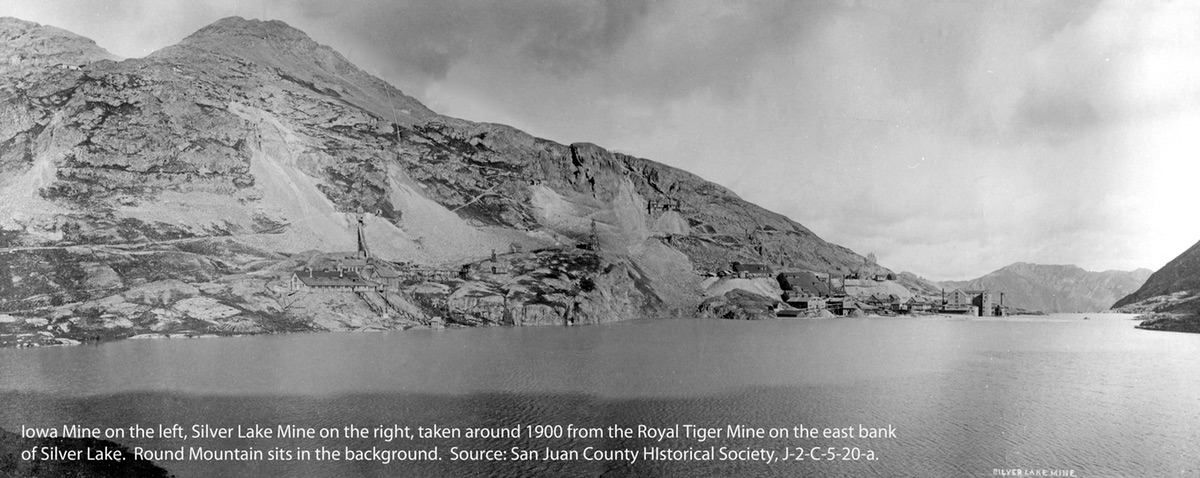

Examining the flank of Round Mountain on the valley’s west side, Reed quickly found several veins that carried silver, lead, and copper. He staked two claims on Round Mountain, which he named the Whale and the Round Mountain, as well as a third, the Silver Lake, on the northwest side of the lake.5

Also in 1876 an unknown prospector working at the hanging valley’s head identified a huge fault up Arrastra Gulch just south of the lake and traced it southwest, where it disclosed a vein he claimed as the Buckeye. During that summer, both he and Reed excavated shallow workings to prove ore and retain title to their properties, then left for the season. When the men returned the following year, Silver Lake Basin, as the valley came to be known, saw its first production, which the owners shipped by burro to the Greene Smelter just north of Silverton.6 However, the volume of payrock was insignificant considering the arduous and perilous approach, which hindered Reed and the other prospector from packing much out and from importing any beyond the most essential materials, limiting output.7

That year also saw Jonathan Crooke and his brother, Lewis,8 purchase the Royal Tiger claim9 on the southeast side of Silver Lake, which they began working in 1877. In 1878 they sold a controlling interest to McPherson Lemoyne. Meanwhile the original miners labored on the Buckeye for approximately three years and, although they had not exhausted the vein, that holding fell silent around 1879.10

Silver Lake Basin pulsed with activity in 1881. A few other prospectors made the hazardous ascent into the cirque, where they examined the east flank of Kendall Peak a short distance south of Reed’s ground. After climbing rock cornices,11 they found a rich vein directly west across the lake from the Royal Tiger,12 staked it with the Iowa and Stag claims, and blasted a tunnel and shaft to explore the lode at depth. At the end of the season, the party had samples assayed in Silverton. The report found the ore was rich not only with silver and industrial metals but also gold. The next year the group returned and began production. The members persuaded a crew of ten or so miners to make the sheer cliff at the Iowa their home for the working season and carried up all the supplies and lumber necessary to build a basic surface plant.13

By 1881 early prospectors had claimed the four significant properties in Silver Lake Basin: the Silver Lake, the Buckeye, the Royal Tiger, and the Iowa.

While the Iowa miners acclimated, John Reed toiled on his adjoining Silver Lake real estate a short distance to the north. During 1880 and 1881, he traced the Silver Lake vein for a considerable distance with shallow excavations hewed into solid bedrock. In the short working season of 1882 he generated several tons of ore from a tunnel he drove at a snail-like pace directly on the vein for a distance of around fifty feet. Remaining in the basin for the winter, with its heavy snows, would constitute a life-threatening event, forcing him and other miners down each autumn.14

During a stay in Silverton in 1883, Reed convinced John W. Collins that his Silver Lake and Round Mountain claims would pay well, if worked, but they required additional investment. For a share of the Silver Lake, Collins joined Reed to form a partnership, and that summer the men scrambled into the basin to resume production. They packed in enough lumber and equipment to build a small blacksmith shop and cabin, and hired three or four miners to begin a second tunnel. Once they reached the vein, the party extracted more or less five tons of material per day and hauled it down to Sweet’s Sampler15 in Silverton.16

About that time, on the east side of the basin, Julius Johnson cut a tunnel deep into the Royal Tiger claim. An old-time prospector, he had leased the property from McPherson Lemoyne. His contract ended in roughly 1883, when Lemoyne sold the Royal Tiger to Edward Innis, who hoped to approach his fabled lake of gold from the opposite side of King Solomon Mountain should his Highland Mary Mine, located at the east end of Royal Tiger Basin, fail to make a discovery.17

However, by 1885 activity in Silver Lake Basin had slowed, probably due to the national recession that began in March 1882 and lasted until May 1885, coupled with difficulties the extreme terrain posed. Reed and Collins stopped work at the Silver Lake Mine, and around that year the Iowa also became idle. The Royal Tiger remained the only active operation.18

Otto Mears, wagon-road and railroad magnate known as the Pathfinder of the San Juan, initiated his interest in the mining industry in 1886 by leasing the Buckeye, which had been dormant since around 1879. He constructed the best surface plant in the basin to sustain a crew of ten in order to produce all year long. Relative to the era, the Buckeye Mining Company was progressive, boasting a ventilation blower that forced air underground and warming boxes so miners could thaw frozen dynamite prior to use. The mine worked at full capacity in 1887 but two years later, Mears quit his contract and closed the property.19

In 1888 Benjamin W. Thayer and James H. Robin examined the Iowa Mine, located a few hundred feet above lake level directly south of the Silver Lake. They found a vein that offered an unusual combination of gold, silver, and galena, the principal ore of lead. The partners leased the ground the following year, began production, and benefited when Congress passed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890, which required the U.S. government to buy nearly twice as much of that metal as before for coining silver dollars.20 The legislation restored silver’s market price and raised the value of the Iowa’s ore. Thayer and Robin boosted their workforce to expedite development and then discovered a second vein of galena, which ensured greater profits.21

The Stoiber Era

In the Las Animas District, the key mining outfits that managed to survive the 1882 recession were among the first to boom in response to the positive climate of 1890, and several of these resided in Silver Lake Basin. What followed laid the groundwork for that small area to become one of the most advanced centers of mining technology in Colorado.22

While the Iowa was a confirmed bonanza, developments on the Silver Lake claims a short distance north soon overshadowed Robin and Thayer’s relatively simple operation. Sometime after 1885, Edward George Stoiber and Gustavus H. Stoiber apparently purchased the Silver Lake Mine from John Reed and John Collins. After running the Stoiber Brothers Sampling Works on the northwest edge of Silverton for four years, the owners had a significant disagreement in 1887 and divided their mutual assets. Gustavus assumed the sampler and Edward, the Silver Lake claims, which numbered two hundred.23 Gustavus’ choice was safer because the works provided a reliable source of income, whereas Edward based his decision on the belief the mine would afford great rewards for its high risk.24

After Edward took control of the Silver Lake property, he spent two years examining the geological features contained in the Whale,25 Silver Lake, and Round Mountain claims; conducting assays; staking more claims with the aid of his new wife, Lena; and calculating the optimal manner of development. Unlike most mine owners, Edward took a primary interest in the bountiful low-grade ore and considered the high-grade a bonus. However, he faced the problem that the costs of shipping inferior payrock out of the basin and processing it at the sampling works would exceed returns. Stoiber realized that if he could mine and concentrate the ore in large volumes with a highly efficient system, economies of scale would render the low-quality material profitable at a nominal cost per ton. By 1890, at the age of only 35, the German engineer had designed a plan.26

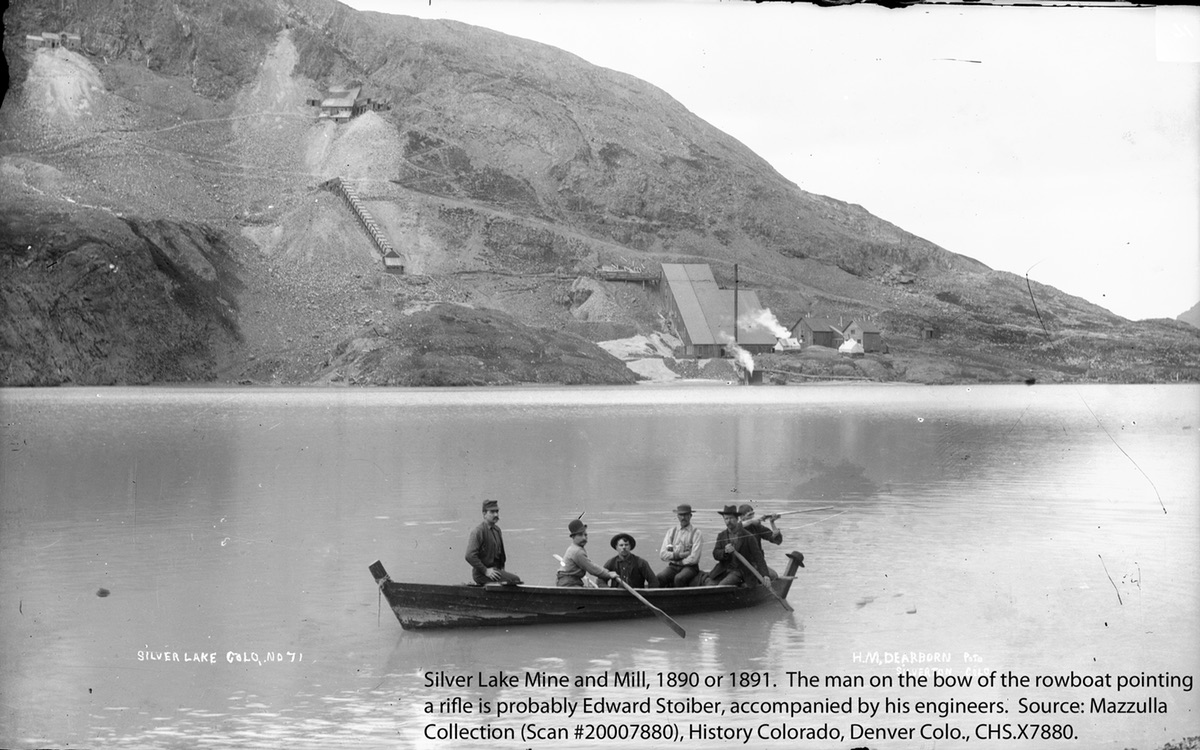

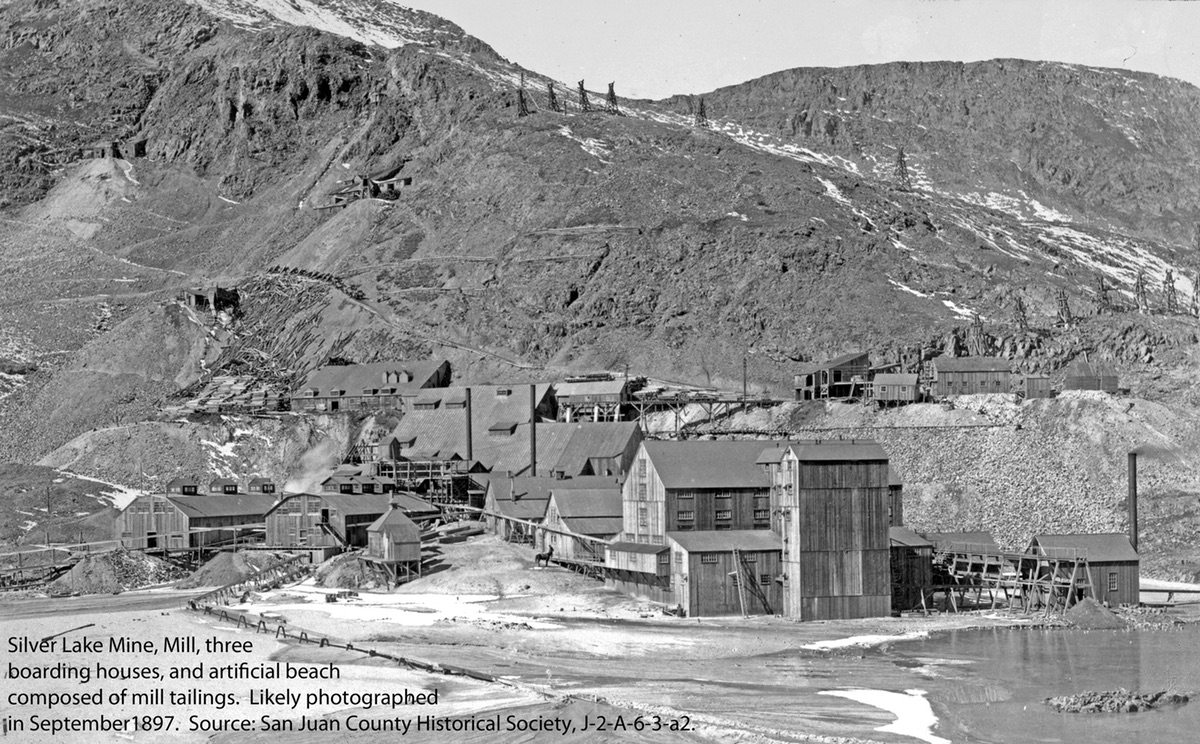

During the late spring of that year, when Silver Lake Basin’s snow blockade consolidated, a small army of workers with mule trains packed in thousands of board feet of lumber, tons of construction hardware and bricks, and the basic necessities of life to Stoiber’s mine. There, at lake level, far above timberline at an elevation of 12,250 feet, they assembled the largest surface plant and mill27 yet in the Las Animas Mining District. Mules drew ore cars on rails from the mine’s underground stations to the mill,28 the first built at that altitude. A new story-and-a-half boarding house accommodated a crew of fifty. Workers manipulated heavy timbers for a stout tunnel house that would enclose a blacksmith shop for sharpening drill steels,29 which miners dulled on a daily basis, in addition to carpentry and machine shops.30

Laborers at this original Silver Lake Mill, adjacent to the mine on the northwest side of the lake, first separated out the larger, heavier pieces of solid “shipping ore.” Then from pulverizing the rest of the low-grade product, they generated fifty tons of concentrates per day, which translated into five railroad cars of freight and provided Stoiber his economy of scale. Constructed on at least three stair-step terraces, the mill used gravity, with the aid of water pumped from the adjacent lake, to draw the material through treatment, after which workers dried the slurry31 and sacked it for shipment. Half the value of the output32 came from gold and the remainder, from silver, lead, and copper.

Stoiber implemented several innovations that set his mill apart from others in the area. Its enclosed coal-fired power plant created enough steam to heat that structure as well as the boarding house.33 Also, a flume carried at least 500,000 tons of piped mill tailings34 directly into Silver Lake’s north end, creating an artificial beach and a long peninsula that separated the northern and southern lake portions. Unfortunately, this operation, along with those of the mine’s neighbors, killed the aquatic life.35

Around 1891 Edward Stoiber built his own AC power plant, evidently the second in the state, down on the Animas River. Power lines transported electricity two miles, too far for DC (direct current), up to his property at Silver Lake Basin. This facility lit the remote building interiors and ran, to perfection, some small motors in the mill. Also, over the course of the summer, muleskinners hauled up supplies and coal so the mine and mill could run through the winter.36

The Silver Lake Mines Company reported 1891 revenues of $254,90837 (about $6,800,000 in 2015) to the United States Mint; it constituted approximately twenty-five percent of the total production of San Juan County.38 Of course, the company’s heavy expenses offset much of this total, resulting in a smaller profit figure.

After two successful years of mining and milling, Edward Stoiber expanded operations in 1893. Lena, the company’s personnel manager, increased the workforce to 130 and had her husband build a second boarding house, which provided amenities heretofore unseen in the Las Animas Mining District. These included a dining hall, a kitchen equipped with a brick oven, and a water tower suspended in the rafters. Thus the building offered running hot and cold water as well as flush toilets, and steam radiators furnished heat.39

But that year the Colorado mining economic climate worsened. The Panic of 1893 prompted Congress to repeal the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, causing the Silver Crash of that year,40 and as a result, almost every mining company in the Las Animas District closed. Most of the mines that continued operating from the early 1890s into the ensuing depression, including the Iowa and the Silver Lake, were proven gold producers. Edward Stoiber, along with a handful of other mine owners, responded to the Crash not by curtailing operations but by taking the opposite approach. They poured capital into underground development, mechanization, and mill improvements on a scale the county had not yet seen. Their purpose was to extract and concentrate product in economies of scale great enough to dramatically reduce the cost per ton, rendering low-value ores profitable to mine even during the financial decline.41

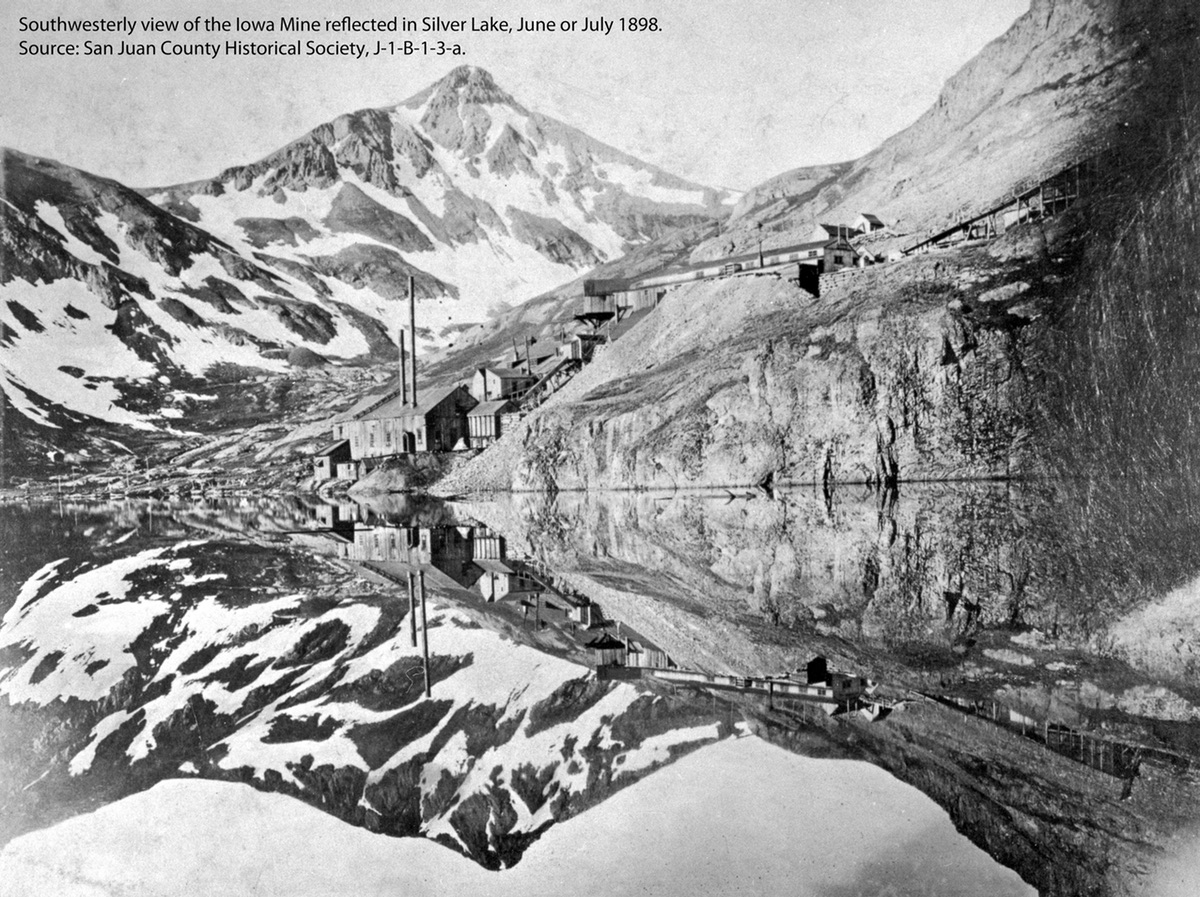

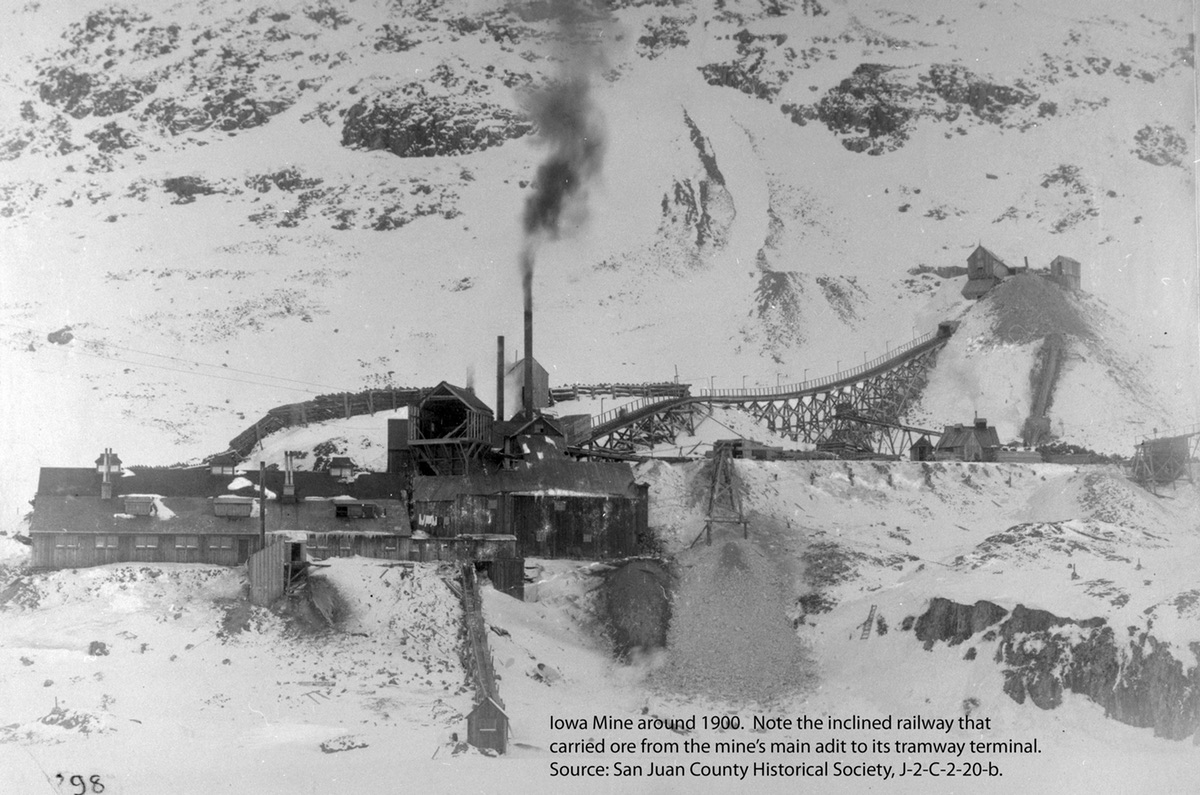

Meanwhile at the Iowa, in 1893 Edward’s Stoiber’s brother, Gustavus, joined Robin, Thayer, and two more investors, H. W. King and R. W. Watson, in organizing the Iowa Gold Mining and Milling Company to labor at that Silver Lake Basin property. This consolidation made the Iowa second only to the Silver Lake in terms of implementing economies of scale, and an enlarged workforce drove two adits into the vein system in order to work it simultaneously at different levels.42

Edward Stoiber built a second AC power plant on the Animas River, which also furnished current to his brother’s Iowa Mine, in 1894.43 Waterwheels ran dynamos to generate electricity for hoisting and pumping and for lighting the remote mines and buildings.44 At the same time, at the Iowa, Gustavus installed the most advanced compressed-air system in the Las Animas District, which provided energy to the piston rock-drills at that mine and, later, the Silver Lake. Gustavus convinced the U.S. Postal Service to locate the misspelled Arastra Post Office at the Iowa in 1895, while Edward housed most of the combined workforce at the Silver Lake.45

During this period, the two Stoiber holdings ranked among the greatest producers in the region, thanks to the owners’ work ethic and, equally important, their frugality.46 They paid close attention to operating costs and squeezed efficiency at each opportunity.47 The brothers’ great success depended on a coordinated effort, which brought about reconciliation. Edward and Lena became two of the largest stockholders in the Iowa company.48

Edward Stoiber’s Silver Lake Mine boasted ten miles of underground passages at numerous adit49 levels to work the vertical veins simultaneously at different elevations, creating an ore factory that yielded silver, gold, lead, copper, and zinc. A central internal shaft linked the various levels.50

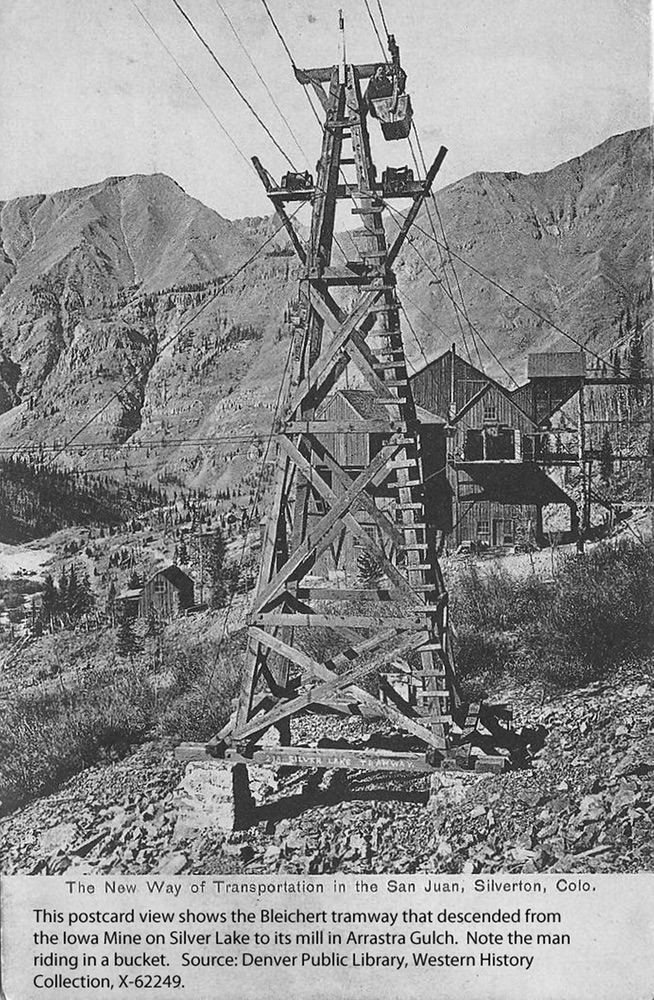

Although his venture earned a profit, Edward realized the need for a more efficient process. Workers could access his mine solely by a steep, mile-long trail that only mules could travel. So in 1895 he contracted with William M. Frey51 to construct an 8,640-foot Bleichert double-rope, gravity-drawn tramway,52 capable of moving five tons of crude ore and concentrates per hour from his mine to a shipping terminal he’d built earlier partway down Arrastra Gulch. Once completed, this tram segment attracted notice for its long spans, one of which stretched almost 2,200 feet across a snowslide area.53

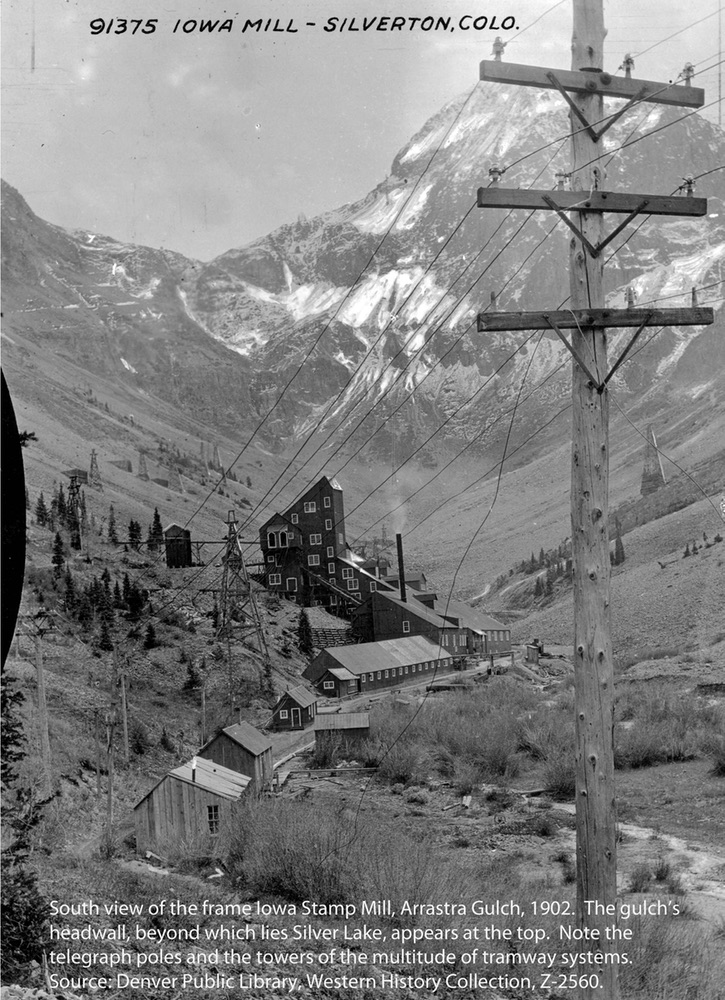

In 1896, with a labor force of 125, Gustavus Stoiber, Robin, and the other Iowa investors made significant progress toward building an empire as large as Edward’s Silver Lake. The partnership hired the Trenton Iron Works to construct its own Bleichert tramway. It ran parallel to the Silver Lake line, terminating at a concentration mill constructed the previous year at timberline in Arrastra Gulch, a mile or so up from the Animas River. The same year, the party gained advantage when it purchased the Tiger Mining & Milling Company, which had just be- gun work on the Royal Tiger Mine, the operation directly across Silver Lake from the Iowa on the lake’s east side. That group had done little with the property because it could not bear the development costs and was eager to sell. Like the Iowa, it yielded mainly lead. Once Gustavus and Robin had erected a surface plant and boarding house there, they invested in underground expansion and increased production.54

Edward Stoiber built a third boarding house at the Silver Lake, five stories high including the basement, which saw completion in 1897.55 At that time the mine employed about 300 workers, many of them immigrants from Austria, Italy, and Finland.56 The newest structure featured the same luxurious amenities as its predecessors and, in addition, a ventilation system, barbershop, laundry room, library, and reading room, as well as bathrooms and spacious “sleeping apartments” that accommodated no more than four men each. The dining room could seat 250 at a time. Stoiber piped in fresh water and collected and burned kitchen trash in a dedicated furnace. Dishwashing machines, drying tables, and two brick ovens ventilated by chimneys adorned the cooking area. The Silverton Standard proclaimed it “the best boarding house in the state, if not in the United States.”57

Unlike the other mine owners in the basin, Edward Stoiber was concerned58 enough with the lake’s water quality to install a primitive sewer system, virtually unknown on the mining frontier, for his boarding houses at the Silver Lake. Mill tailings covered the septic tanks.59

By the end of 1897, the Stoiber brothers had transformed Silver Lake Basin into an industrial landscape. Their three mines, from which an octopus of roads radiated outward, took on the appearance of massive factories, creating noise audible within all the surrounding basins.60

San Juan County’s well-capitalized mining companies, such as the Silver Lake, had utilized electric hoists for raising cages61 between the various levels within the vertical shafts as early as 1895. Ever the progressive, since his mine already had an electrical infrastructure, Edward Stoiber decided to experiment with innovative electric-model drills. By January 1899, miners at the Silver Lake were successfully using these tools in its stopes,62 drawing the attention of industry experts,63 although the machines, while portable and convenient, were somewhat too lightly constructed for the work required of them.64

In 1898 Edward commissioned Frey to build a 6,200-foot tramway extension65 from where the first segment ended at a temporary station just above the Iowa mill, to a massive, newly constructed ore-storage terminal on the south side of the Animas River, west of the mouth of Arrastra Gulch. The project increased the line’s capacity from five to thirty tons per hour. This terminal served as a base station for the Silver Lake Mine and included an assay shop and freight yard. The second tram section enabled Stoiber to haul concentrates from his mine on the lake all the way down to a branch of the Silverton Railroad that Otto Mears constructed especially for him. The two tramway segments together totaled almost 15,000 feet, making it one of the longest systems in the state.66

Despite the successful operation of his elongated tramway, Edward Stoiber’s mill on the lake proved uneconomical. As a result, in 1900 he built a second one at the site of his storage terminal and abandoned the original. The new mill building alone covered two acres and descended from ore-holding bins on flat ground at the top. The product, in various stages of crushing and concentration, proceeded via gravity down a series of ten stair-step terraces to the valley floor. The structure was able to treat 1,000 tons of payrock every twenty-four hours, more than many mines generated in a month.67

Because of Edward Stoiber’s advanced, enlightened concepts of mining, milling, and improving employee worker conditions, his Silver Lake became a model that similar companies across the West imitated by the late 1890s.68 He created a legacy by which his astute contemporaries could learn and profit.

Meanwhile, by 1898 miners at the Iowa had driven around 8,000 feet of underground workings on its four levels. The owners acquired the Black Diamond and other claims and initiated further underground development at their second property, the Royal Tiger. That year they built a tramway segment across the lake that allowed miners at the Royal Tiger, which had no mill, to send its product into the Iowa terminal, where workers coupled the buckets onto the main line. The mobile receptacles then coasted down to the Iowa Mill, where men emptied them and sent them back up to the Royal Tiger and Iowa for filling. In addition, the following year the Iowa partners added another section to their main tramway line. The lengthened system, known as the Iowa-Tiger, extended its reach from the Iowa mill to the company’s own ore-storage and – loading terminal located on the Animas River, where Otto Mears constructed a second spur to furnish direct service on his Silverton Railroad.69 By 1900 the Royal Tiger was producing a greater volume than the Iowa.70

During this period, Edward and Gustavus together drove the Unity Tunnel,71 actually an adit, likely named to reflect their fraternal cooperation. Via this ambitious project, the brothers penetrated 3,000 feet of solid rock to undercut the vein systems of both the Silver Lake and Iowa Mines. Their goal was to provide a platform for miners to stope72 the veins 700 feet upward to the existing operations and to also serve as a central artery through which workers could haul the deep ore out. Although they began boring in 1895, the Stoibers did not complete the connection with the deepest workings in the Silver Lake Mine until 1901. To service the adit, the brothers built another surface plant that included many of the same components found at the two mines.73 Then in 1900 they linked the portal with the main line by tramway.74

In 1899 an unnamed partnership leased the Buckeye Mine, the fourth player in Silver Lake Basin, idle since Mears quit his contract ten years earlier. The investors rehabilitated the critical excavations and began production, mainly of lead ore,75 and activity lasted several years. This venture marked the last known occupation of the site, which lacked a mill. However, individuals or small companies could have worked it some time after that.76

In early 1901, after completing the Unity Tunnel, Edward Stoiber sold his Silver Lake mining properties to the Guggenheim family’s exploration company for $2,350,00077 (about $67,708,000 in 2015). He stipulated the corporation would retain him as consultant until the new mill was finished and treating ore successfully, which proved true that May.78 Then he and Lena retired to Denver and traveled Europe.79

Subsequent Progress and Decline

Unfortunately the Guggenheims lacked the personal interest and purity of motive Edward Stoiber possessed. Furthermore, within three months of the sale, the principal vein at the Silver Lake pinched out,80 leaving the costly operation with much less payrock than the new owners had supposed. Whether Stoiber knew the situation before the sale remains uncertain. The new manager directed his miners to extract existing ore and drive new exploratory workings in search of the lost vein and others. These undertakings succeeded, exonerating Stoiber. Nevertheless, through 1902 the crew squeezed out just 260 tons of product per day, approximately one quarter of the new mill’s capacity.81

In 1903 the Guggenheim company merged with the giant American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCo),82 which some of the nation’s most powerful smelter men had organized in 1899.83 The combined entity controlled Edward Stoiber’s Silver Lake empire and operated it to both exploit the mine’s profitability and provide a source of ore for its Durango Smelter. But in October 1904 a blaze destroyed the tramway’s turning station above the Iowa Mill, pulling over a number of towers on the Silver Lake and Unity segments, and, in the process, dropping all their buckets. The accident resulted in halting the entire operation. The domain’s manager, Rowland Cox, could have brought the old mill at Silver Lake Basin back online but declined to do so.84

H. A. Guess, mill assayer, replaced Cox in 1905 and returned the Silver Lake Mine to full production. But April 20, 1906, an arsonist set fire to the new Silver Lake Mill on the Animas River, causing $250,000 in damage85 and destroying, as well, the lower tramway terminal. Guess ordered a second suspension of operations at the mine. On April 21, the day after the mill burned, at the age of 51, Edward Stoiber died of typhoid fever while on vacation with Lena in Paris.86

Later that year ASARCo initiated construction of a much smaller replacement mill on the same site and workers completed it in 1907.87 But then another national recession struck.88 The company closed its new facility in 1908 and leased out blocks of ground at the Silver Lake to small parties instead of working the mine itself.89

Over the next few years, a number of natural calamities took a toll. In 1909 the Silver Lake tramway’s turning station burned again and wrecked the system.90 Then in 1911 a series of avalanches took out towers on both the Silver Lake and Iowa tramways and started a fire at a transformer station.91 In 1912 another blaze that started at the Silver Lake’s blacksmith shop destroyed the upper tramway terminal in addition to virtually all the property’s buildings, except one of the boarding houses. As a result, the corporation gave up large-scale production but continued to farm out blocks of ground to small groups. Ironically, in contrast to Edward and Lena Stoiber, ASARCo never earned a profit from the Silver Lake, although the company employed competent engineers.92

Meanwhile, during the early 1900s the Iowa Gold Mining & Milling Company, second- largest outfit in the Las Animas Mining District and one of the county’s most profitable, experienced misfortunes that rivaled those at the Silver Lake. Gustavus Stoiber and James Robin discovered that the main problem with chiseling out ore in economies of scale was that a mine’s life was relatively short, since its reserves were limited. By 1901, after only six years of intensive mining, the Iowa showed signs of exhaustion, in contrast to more than fourteen at the Silver Lake.93

In response, the Iowa’s owners pursued an aggressive exploration and development campaign. But when that plan failed, they halted mill and tramway operations and leased out both the Iowa and Royal Tiger while seeking a buyer. Because of the meager output from both properties, no one, including the Guggenheims, seriously considered purchasing the complex. Although in 1902 miners working for Al Kunkle, lessee of the Royal Tiger, struck a new vein rich in gold and silver and over five feet wide, it lasted only a year before giving out. Consequently he, followed by the lessees at the Iowa, moved on to other endeavors.94

The stress of the Iowa’s rapid failure proved too much for the owners. James Robin shot himself in 1903. Two years later, an avalanche wrecked a significant portion of the Iowa Mill and soon after, Gustavus Stoiber died of a massive stroke.95

After these tragedies, Stoiber’s and Robin’s inheritors abandoned hopes the Iowa and Royal Tiger real estate would return to profitability. But in 1908 Otto Mears and Jack Slattery approached the heirs with a proposal to lease the entire idle operation, including the Iowa Mill. The owners accepted, and the lessees embarked on the beginning of a long-lasting, lucrative syndicate.96

Mears and Slattery rejected the conventional view that labor costs were an expense merely to be tolerated, believing instead their success hinged on the quality and loyalty of their miners. So they hired the most competent ones they could assemble and initiated a profit-sharing program to provide employees an incentive to find payrock and produce it efficiently. They also persuaded a number of other investors to join their company in order to finance repairs, improvements, and equipment. Then they rehabilitated the surface plant and underground workings at both the Royal Tiger and the Iowa and undertook an organized ore-exploration program.97

In 1909 workers at the Iowa sank a shaft and discovered an extension of the valuable Melville Vein, whose upper levels Robin and Gustavus Stoiber had previously identified and mined. The following year, elsewhere in the excavations, another crew discovered a gold ore vein valued at $1,200 (about $30,900 in 2015) per ton. Later in 1910 the foreman at the Royal Tiger blasted a chamber out of a vein’s hanging wall;98 the shot revealed a hidden, parallel vein rich with free gold.99 The partners sent the newly discovered payrock via tramway down to the Iowa Mill for processing. Thus Mears and Slattery kept over one hundred employees busy through 1912. The miners made several more discoveries, too, and heavy production continued through 1913. But an avalanche destroyed the Royal Tiger boarding house that year and after five years of continuous yield, the lessees finally saw operations at the Iowa and Royal Tiger slow.100

To raise capital, Mears, Slattery, James Pitcher, and a few other investors organized another syndicate. In 1913 they leased the dormant Silver Lake from ASARCo and rehabilitated the Stoiber Tunnel, the mine’s principal entry, which Edward had constructed to intersect the Nevada vein. The partners generated low-grade ore through 1914 and contracted for additional ground. The burgeoning combined Iowa and Silver Lake workforce justified reopening the Arastra post office, which the government had closed in years past. The company maintained a constant but limited production into 1917, when experienced miners noticed an eight-foot-wide vein laden with copper, silver, and gold in the walls of the Stoiber Tunnel. They sent its material, along with the rest they extracted, down to the Iowa Mill for treatment.101

The Mears entity was not the only one to labor at the Silver Lake and Iowa Mines during the first years of World War I. Small parties of lessees, mostly Italians the Stoibers had previously employed, squeezed out modest output from their claims. The Unity Tunnel saw activity, as well, from groups that may have contracted directly with ASARCo to work ground above and below the tunnel level. Also, several partnerships pooled their capital and modified the idle Bleichert tramway at the Unity so that it terminated near the Iowa Mill, where the lessees sent their product for processing.102

At that time the Iowa Mill served as the center for ore concentration in and around Silver Lake Basin. To improve the recovery of metals, in 1915 Louis Bastian, former superintendent of the Silver Lake Mill, installed flotation equipment, which relied on oil or detergent to float metalliferous material off and away from waste. Then the facility attracted ore from miners located in the surrounding territory and in 1916 alone, produced 700 tons of concentrates from just the Iowa Mine.103

In 1913 Mears commissioned a novel project that involved the expansive original mill-tailings dump on the shore of Silver Lake, which, in essence, constituted a ready form of extremely low-grade ore. He hired Arthur Redman Wilfley to build a unique mill on the north side of the Animas River opposite Arrastra Gulch for processing the product with specialized equipment. Sand pumps mounted on a barge vacuumed up approximately eighty percent of the total and piped it as a slurry over to the outlet of Silver Lake, from which a wooden flume descended steeply down the headwall along the gulch’s west side. A trestle carried the flume out beyond the mouth of the gulch and over the river to the mill.104

But the enterprise ran into trouble in early 1915. The flume developed leaks because the slurry acted like liquid sandpaper, rapidly wearing the wood. In addition, Wilfley’s new mill machinery failed to perform as expected and Mears replaced it with flotation. He also lined the damaged plank trough with concrete. As a result of this troubleshooting, from 1915 through 1918 Mears’ railroad hauled away dozens of rail cars of concentrates from the treated tailings, garnering over $100,000 (about $2,058,000 in 2015) in the profitable operation. The structure functioned smoothly into 1919 when, having exhausted the richest and most debris-free material, Mears closed it.105

In 1917 and 1918 Mears’ syndicates continued to lease the Iowa and Silver Lake Mines, along with the nearby Mayflower and Highland Mary,106 located, respectively, to the north and east of Silver Lake Basin. World War I had boosted the demand for industrial metals. At the same time, because of its political and economic value abroad, silver increased in price to a level not seen since Congress passed the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890.107 During 1918 miners at both the Iowa and Silver Lake worked around the clock in three shifts.108

But in November Slattery suspended operations at all the syndicates’ mines following the outbreak of the Spanish influenza pandemic, which decimated the crews, and had the boarding house at the Silver Lake fumigated. He faced a difficult time finding replacement workers and reopened only the Iowa in 1919. At that juncture the Southwestern Mining Company and the Melville Leasing Company renewed their contracts for the Iowa, cutting the workforce to forty, but not those for the Silver Lake, in effect signaling an end to that mine’s run.109 The Iowa Mine then remained one of the Las Animas District’s best producers through 1920, when operations collapsed because its workings, like those of the Silver Lake, were running out of ore. As with the Silver Lake Mine, individuals and small companies leased portions of the Iowa until the mid-1920s, but major activity did not resume.110

Earnest Biondi and four other miners leased the Royal Tiger in 1923 and worked the mid- level stopes, marking its last recorded occupation. The Iowa Mine was the scene of the most sizable late-date effort, for in 1926, the Colorado-Mexico Mining Company employed seven miners there and continued limited work until at least 1931. Charles Chase, engineer at the Mayflower Mine, provided concentration services at the Iowa Mill.111

In 1937 or 1938, Chase commissioned the Silver Lake Cross Cut, a passage driven southwest from Little Giant Basin toward the deepest excavations in the Silver Lake Mine. He negotiated a lease with ASARCo, which still owned the ground. Using a jumbo rig with four automatic drills, his workers bored 24 hours a day until, after driving thousands of feet, by 1940 they reached the Silver Lake Vein. Some of the material they located was higher in grade than Chase had expected and he began production. Then the giant corporation decided it wanted to mine its own property and Chase secured a reverse lease, which afforded him royalties and compelled ASARCo to maintain the crosscut and finance additional development. The lucrative contract lasted eight years.112

* * *

Historically, the Silver Lake, Iowa, Royal Tiger, and Buckeye constituted the working mines in Silver Lake Basin. In their heyday, the Silver Lake Mines Co. and the Iowa Gold Mining and Milling Company owned most, but not all, the claims, of which some overlapped and some extended under the lake. In 1891 the claims under various ownerships carried these picturesque names:113 Yellow Jacket, North Star,114 Big Bear, Thornton, Ulysses, Good Fortune, Cross Cut, Little Shaver, Martha U.F., Arabian Boy, Silver Spur, Round Mountain, Gretchen, Maxwell, Black Diamond, Stag, Rochester, Whale, American Boy, J.W. Collins, Grip, Melville, White Diamond,115 Belle of the West, Keystone, Sinaloa, Eclipse, Pickwick, Silver Lake, Iowa, Royal Tiger, Royal Tiger No. 1, and Buckeye. By 1905 the number of claims in Silver Lake Basin had more than doubled.

Silver Lake Basin occupies a niche without parallel in Colorado mining history. Located only four air miles from Silverton, the region’s metropolis and trading center, the cirque lies in a site so remote that it hindered early exploration and development. It first saw prospectors in 1876, so production came well after documented activity as early as 1860 at the floor of adjacent Arrastra Gulch.116 Following the Silver Crash of 1893, the basin’s output defied the statewide trend and ranked among the greatest in the district.

Silver Lake Basin witnessed innovation, including the introduction of AC power to its mines, compressed-air systems, and electric-model drills, ahead of the rest of the San Juan area. Domestic amenities introduced at its boarding houses included flush toilets, dishwashers, and a septic system. Some of the longest tramways in the Las Animas Mining District served its mines.117 Despite the challenges that devastating fires, avalanches, legislation, and sickness posed, its miners persisted in extracting the riches their veins offered.

Edward and Gustavus Stoiber were paramount among a handful of pioneers who developed the practice of mining and milling low-grade ores in economies of scale, and they applied their expertise at Silver Lake Basin. For over a decade, they, with the aid of their partners, established a monopoly that expanded and controlled the locale’s output, an arrangement that at this time might violate antitrust laws. With their German work ethic, these two brothers epitomized the strike-it-rich success story on a scale their peers surely envied.

Silver Lake Basin Today

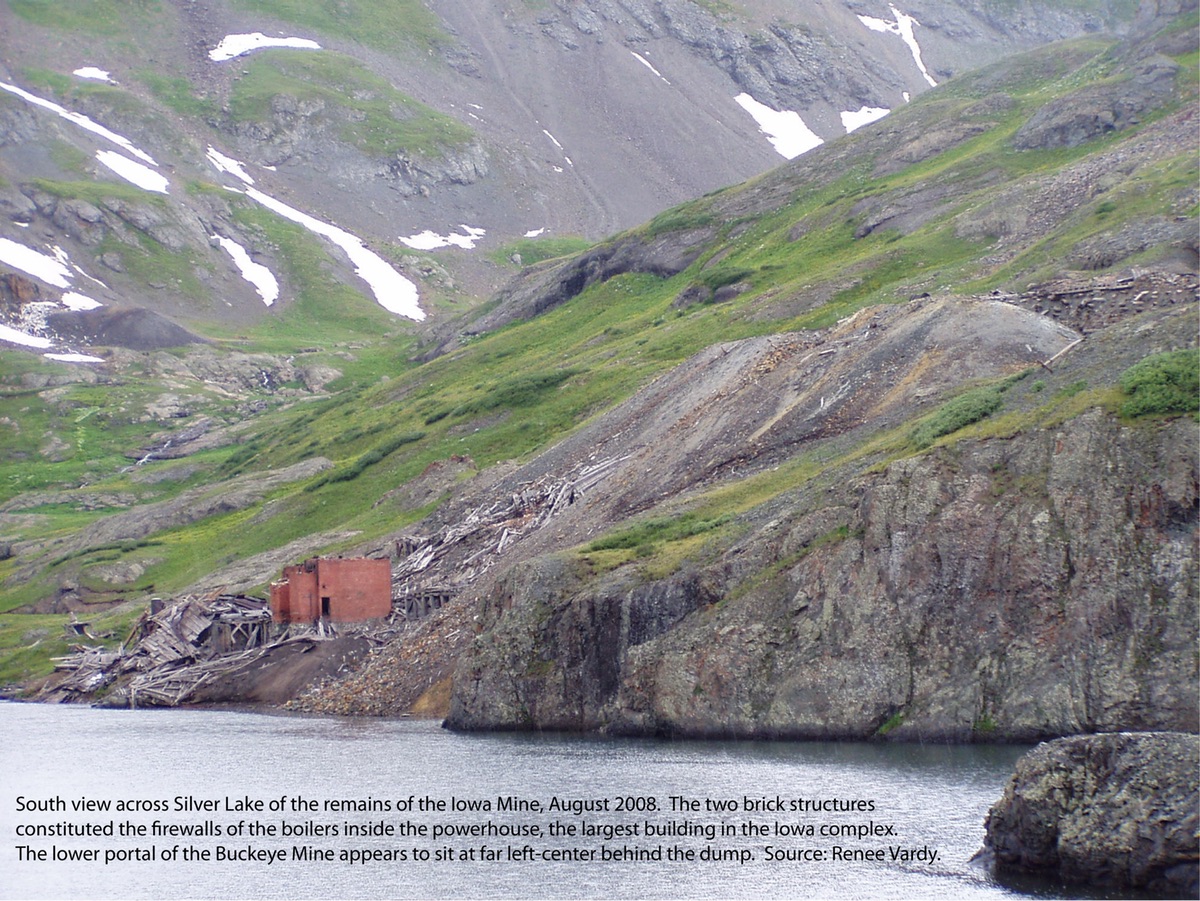

In 2015 ASARCo owned the claims that comprised the four mining properties situated at Silver Lake.118 Scant evidence of the basin’s once-abundant, state-of-the art surface structures remains, and the area constitutes an archaeological site.

Silver Lake holds contaminated water, with an increasing metal concentration at depth,119 resulting from the submerged mill tailings and mine dump rock. An analytical study published in 2009 identified the primary pollutants as lead, zinc, iron, aluminum, copper, and cadmium. But of these metals, only lead tested above the MCL120 (maximum contaminant level), the reading at which a toxin in drinking water poses a known or expected health risk. At the time of the study, water bugs made up the only evidence of life in the lake.121

Visiting Silver Lake Basin

Accessing Silver Lake today is scarcely easier than when John Reed staked his claims in 1876 because time has witnessed the passage of the tramways and most of the mule trails. Two options are available. The more direct route involves driving east of Silverton two miles along County Road 2. At the renovated Mayflower Mill, turn south and wind down a hill. Cross the wide bridge over the Animas River at the mouth of Arrastra Gulch and continue 2.5 miles or so, on foot or in a 4X4 or OHV (off-highway vehicle), to the Mayflower Mine site. You will en- counter several forks in the road; just follow the tramway towers, still standing, up to the mine. Then, from the trailhead where the road ends, hike about 1.25 miles to the top of the headwall and on down to Silver Lake. Allow at least four hours to make the trip from the mine up to the lake and back. This trail has several steep switchbacks that cut across scree (detritus) where cribbing122 has given out and a rope helps hikers navigate a rock ledge. Use extreme caution here. Generally, you can make the trip in late July but the prime times stretch from August through the beginning of October. Even then, huge avalanche debris fields that do not completely melt can cross the trail, requiring extra vigilance. The Silverton Visitors’ Center can provide further information for planning your trip.123

The second access option, safer but much longer, involves hiking or driving south (OHV or 4X4 vehicle only) from the Silverton city limits on County Road 33, the Kendall Mountain Road, which skirts the mountain’s base. You’ll find an old USGS topographical map along with a modern GPS unit helpful. Approximately two miles from Silverton, the road splits. The left fork proceeds up Kendall Gulch to the abandoned Titusville Mine, with a branch ascending close to the top of the mountain. Follow the right fork, County Road 33A, the Deer Park Road, which miners of old employed to haul in timbers to Silver Lake Basin by burro.124

Where Deer Park Road nears Deer Park Creek, you have two choices. Choice 1: You can continue driving on the road a quarter mile, then veer to the left on foot and hike east on a pack trail. Eventually it climbs steeply northeast and leads to the Buckeye Mine site above the south shore of Silver Lake.

Or, Choice 2, you can keep driving east on Deer Park Road, north of the creek, about a mile until you reach the marsh north of the Montana Mine site. Opposite the access road to this mine, leave Deer Park Road and take the Buckeye Trail, which heads north and becomes a braided elk path through the woods. In time it climbs northeast and intersects the pack trail referenced in Choice 1, taking you to the Buckeye Mine site.125

Obituary for Edward G. Stoiber126

Edward G. Stoiber, who died suddenly in Paris, France, April 21, was one of the leading mining men and metallurgists of Colorado. He was born in Germany in 1854, and graduated from the School of Mines in Freiberg. He came to Leadville from Germany as early as 1879, and for three years followed his profession as mining engineer. From there he went to Silverton,127 where he established a sampling plant, gradually drifting into the business on a large scale by acquiring several properties in that vicinity. These smaller claims he ultimately expanded into the immense Silver Lake property, which he sold to the Guggenheim Exploration company for $2,350,000 about four years ago. After the consummation of this deal, Mr. Stoiber withdrew from active business and practically lived a retired life. When not in Denver, he spent his time in European travel. He was in Port Arthur only a short time previous to the Russian-Japanese war, and returned from there over the Siberian railroad before the declaration of war.

During his active career Mr. Stoiber devoted himself closely to his work at Leadville and Silverton, and it may fairly be said that he was one of the first who was successful in the treatment of low-grade mixed sulphide ores at a profit. As an operator, Mr. Stoiber did everything in his power to improve and modernize the mining business. With him it was a science that required deep study. He was on the alert to put into practice new ideas that he believed would rebound to the benefit, not only of himself, but others. It is known that he made frequent trips to the most important concentrating plants in this country and Europe, taking copious notes and sketches of every new device that came before his observation. He introduced many improvements, some original with himself, and did not hesitate to experiment with new devices.

The debt which the mining industry of Colorado owes to Mr. Stoiber is recognized by the practical men who are engaged in it. More than to any other man is due to him the present prosperity in the San Juan region of that state. He had no patience with the irrational system which has filled so many gulches with useless mining plants; but with the soundness in reasoning that characterized the old Freiberg man, he adapted the process to the ore, instead of trying to adapt the ore to the process, and although neither a mine finder, nor an inventor, he solved difficult problems in ore treatment, in a practical way, made money for himself, and taught others how to do it.

As a philanthropist, Mr. Stoiber was always ready to contribute to any worthy cause. His benevolent deeds are well known to the charity workers in Denver. He was always kind and considerate to his employees and was highly esteemed by them. He was much interested in education and made large donations to its aid; he contributed the scientific section to the University Club library and made the gift of an elaborate set of instruments to the State School of Mines.

His ambition was to develop the mining resources of the state wherever practicable, and it may well be said of him that he devoted his life to the interests and welfare of the industry. His loss, at so early an age, will be regretted by a host of friends, among whom are included many who are engaged in the mining industry.