Cripple Creek History

Colorado became a U.S. territory in 1861 and a state in 1876. Bob Womack and his brother William emigrated from Kentucky with their parents and sister to Colorado City (now Colorado Springs), a thriving town east of Pikes Peak. The brothers bought a ranch about forty miles to the southwest, on the west side of Pikes Peak in 1876.

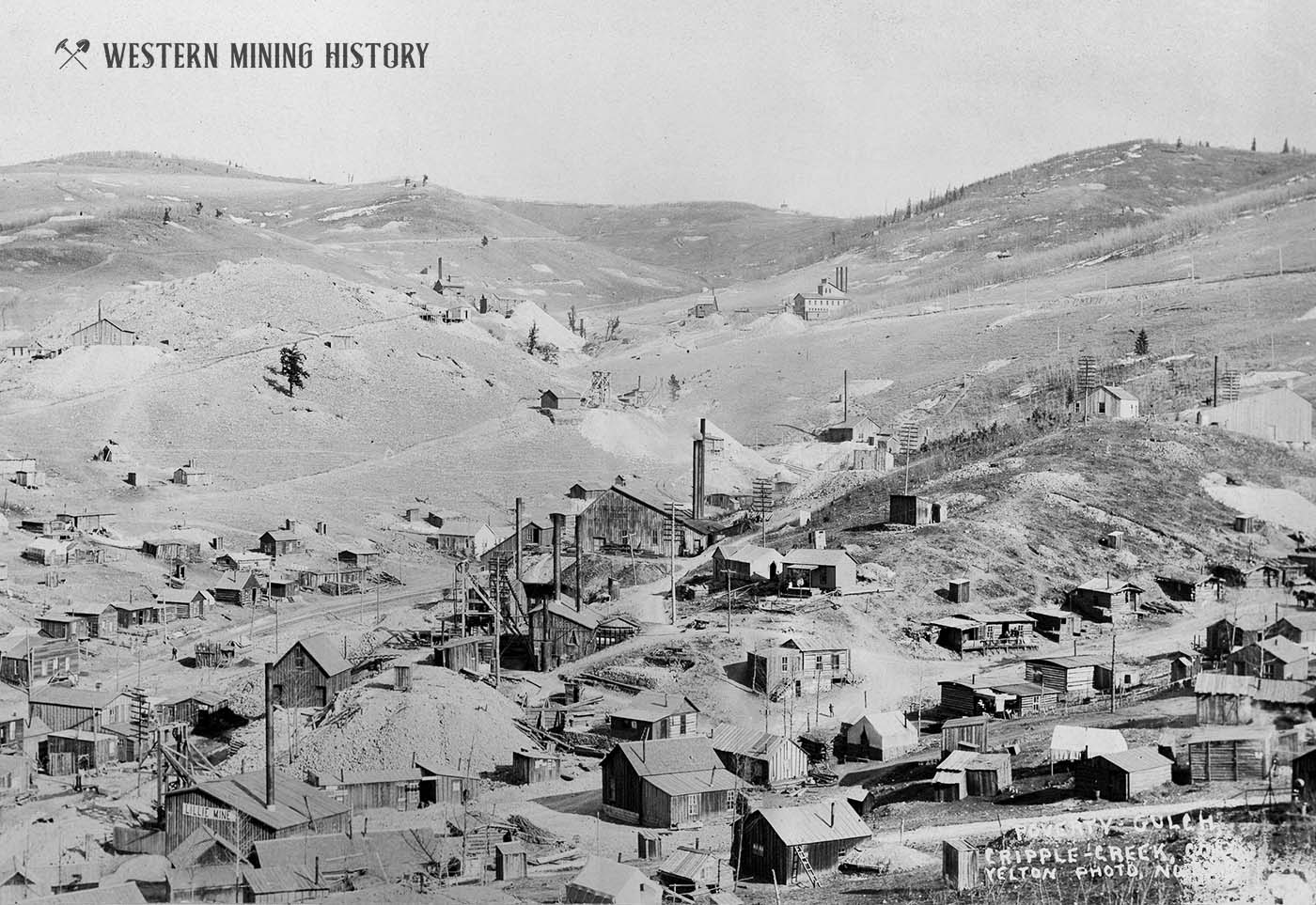

Bob worked on the ranch and prospected for gold in his spare time along the southwest slopes of Pikes Peak for years. He found minor amounts of gold in the local creeks but nothing to write home about, until striking gold in Poverty Gulch in October 1890. Bob filed his claim at the assay office at the county seat, Colorado City, calling his claim the El Paso Lode.

Not too many people took Bob seriously and none were willing to invest in exploratory digging. A gold mine found to be fake years earlier, with salted (planted) gold, may have tainted peoples’ minds to the region west of Pikes Peak.

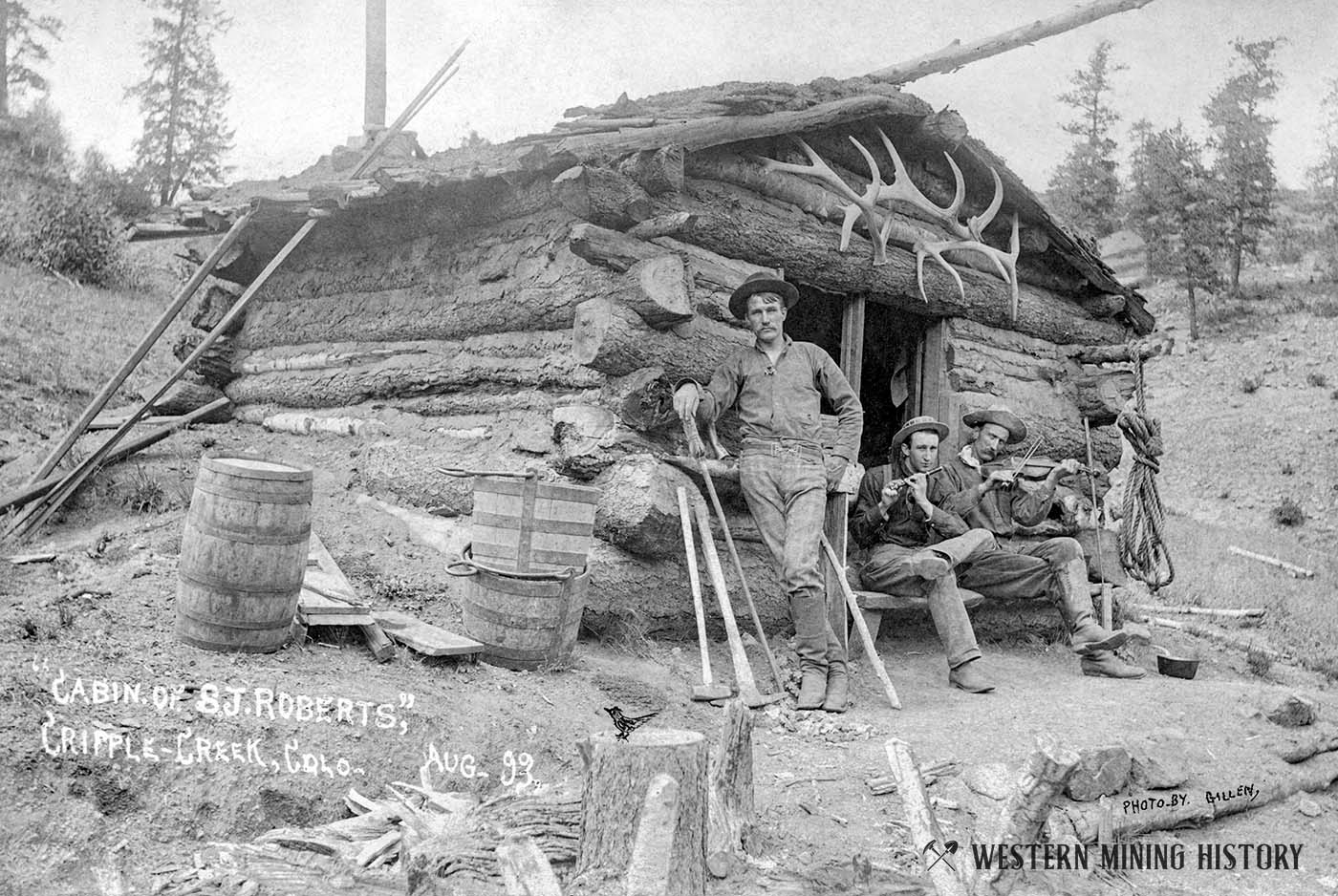

It took discoveries by a few other miners in 1891 to start the greatest gold rush in Colorado history. Word spread quickly, and soon the hills around Poverty Gulch were covered with hopeful miners. You would think that Bob would have become a millionaire, but he sold his claim too early, for only $300. Womack died in 1909 in poor health and far from wealthy.

Winfield S. Stratton was one of the early believers in Bob’s story and ventured over to the Poverty Gulch area. A carpenter from Indiana living in Colorado City, he was interested in mining and had taken some courses in geology at the Colorado School of Mines.

After a few months of exploring the hills, Stratton struck gold on Battle Mountain (near Victor) on July 4th, 1891, naming it the Stratton Independence Mine. Stratton became one of the elite group of millionaires resulting from the area’s gold riches.

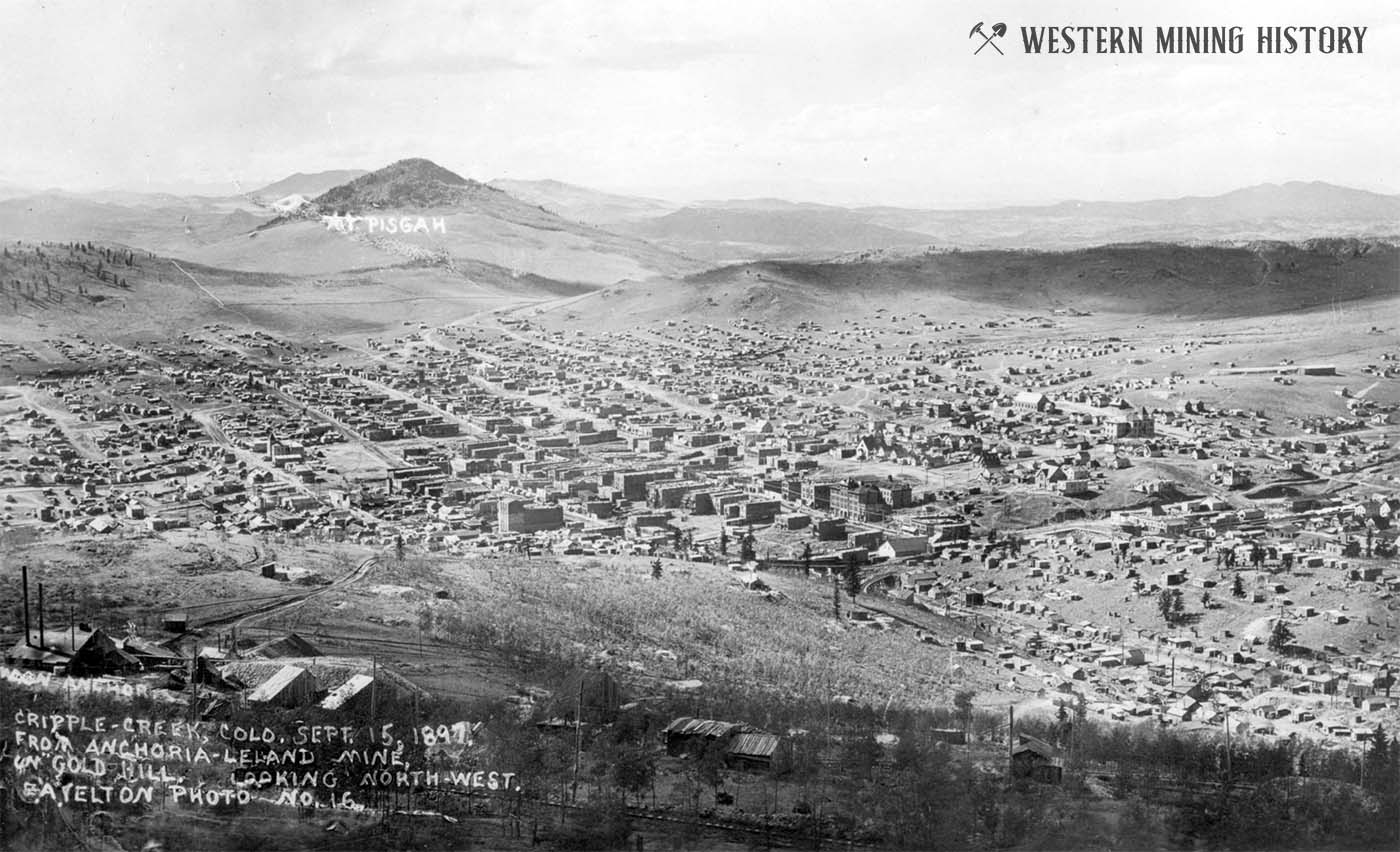

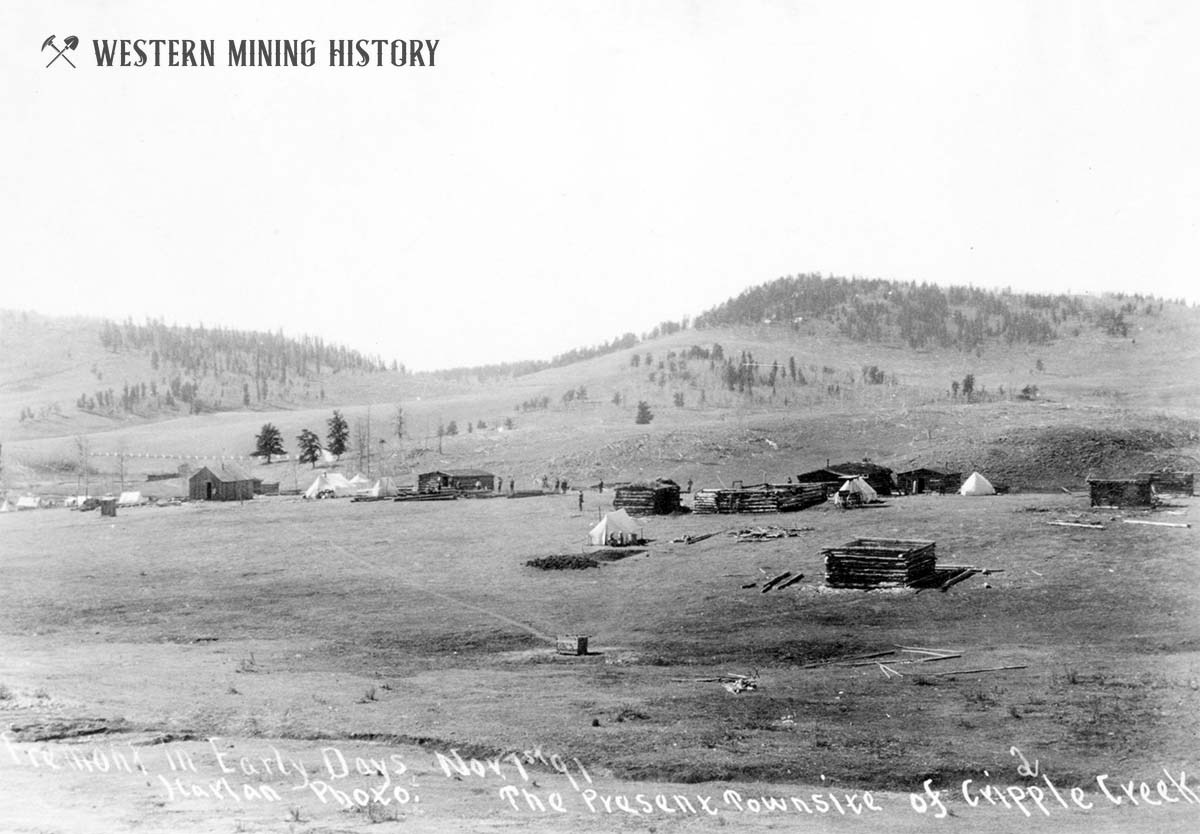

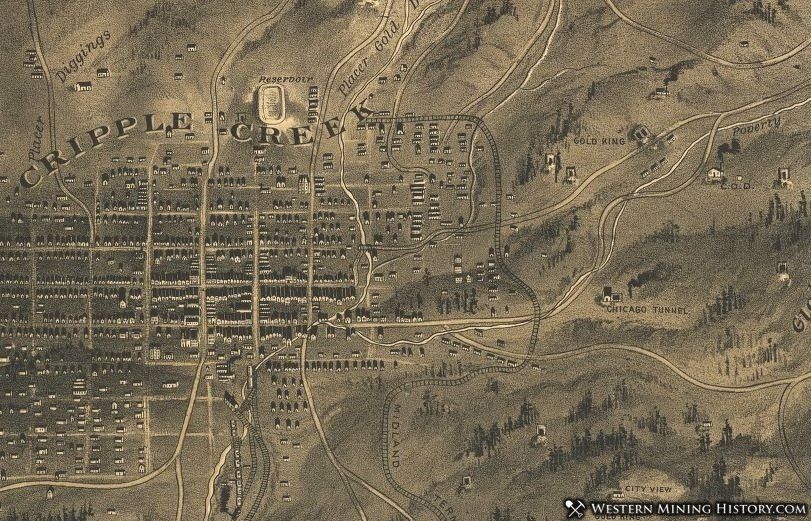

Horace Bennett and Julius Myers grazed cattle on their Broken Box Ranch after 1885 west of Poverty Gulch, near the base of Mount Pisgah. After the gold strikes, Bennett and Myers laid out a town on the ranch. The main street across the center of town was named for Bennett; Myers Avenue was the street to the south.

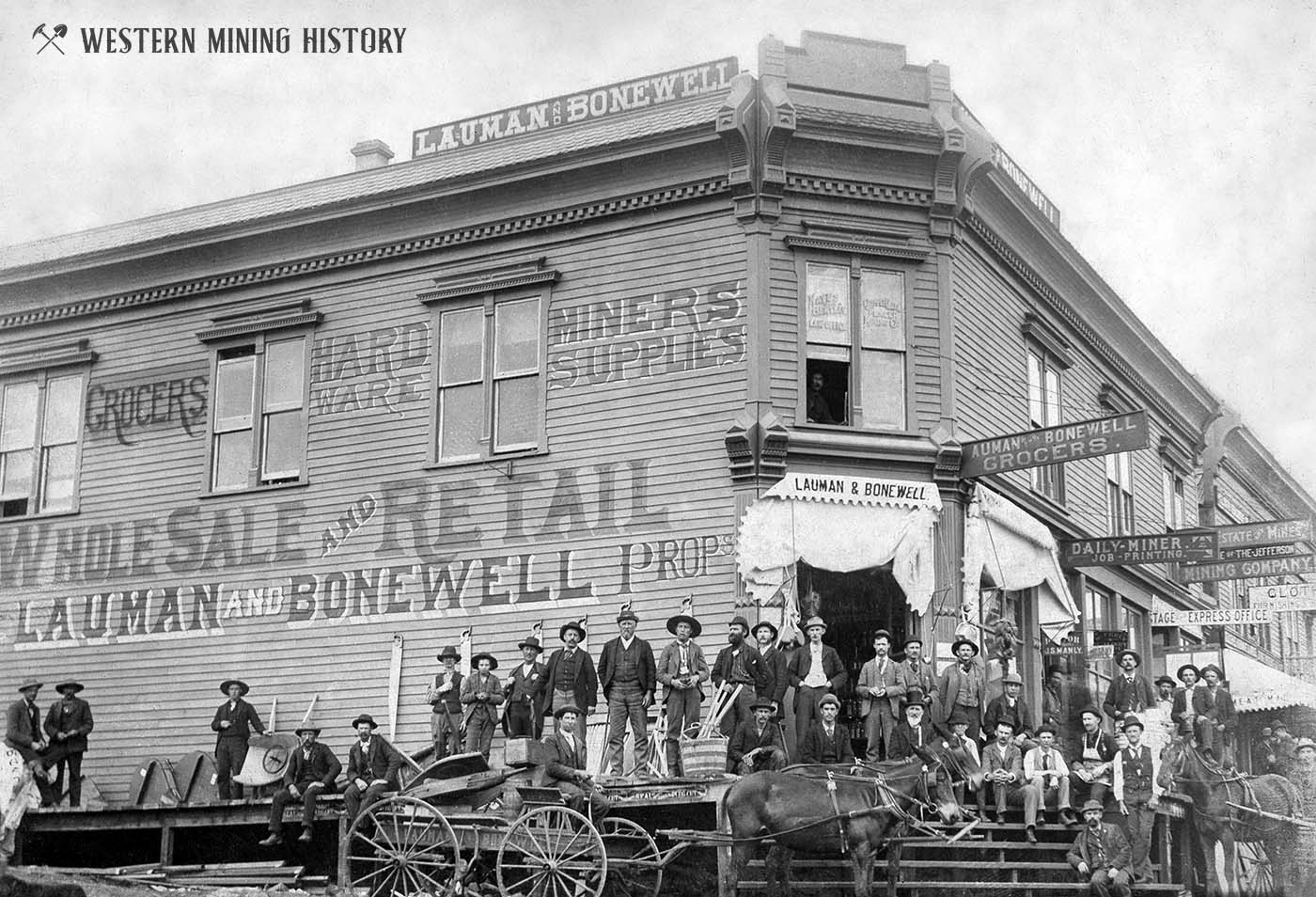

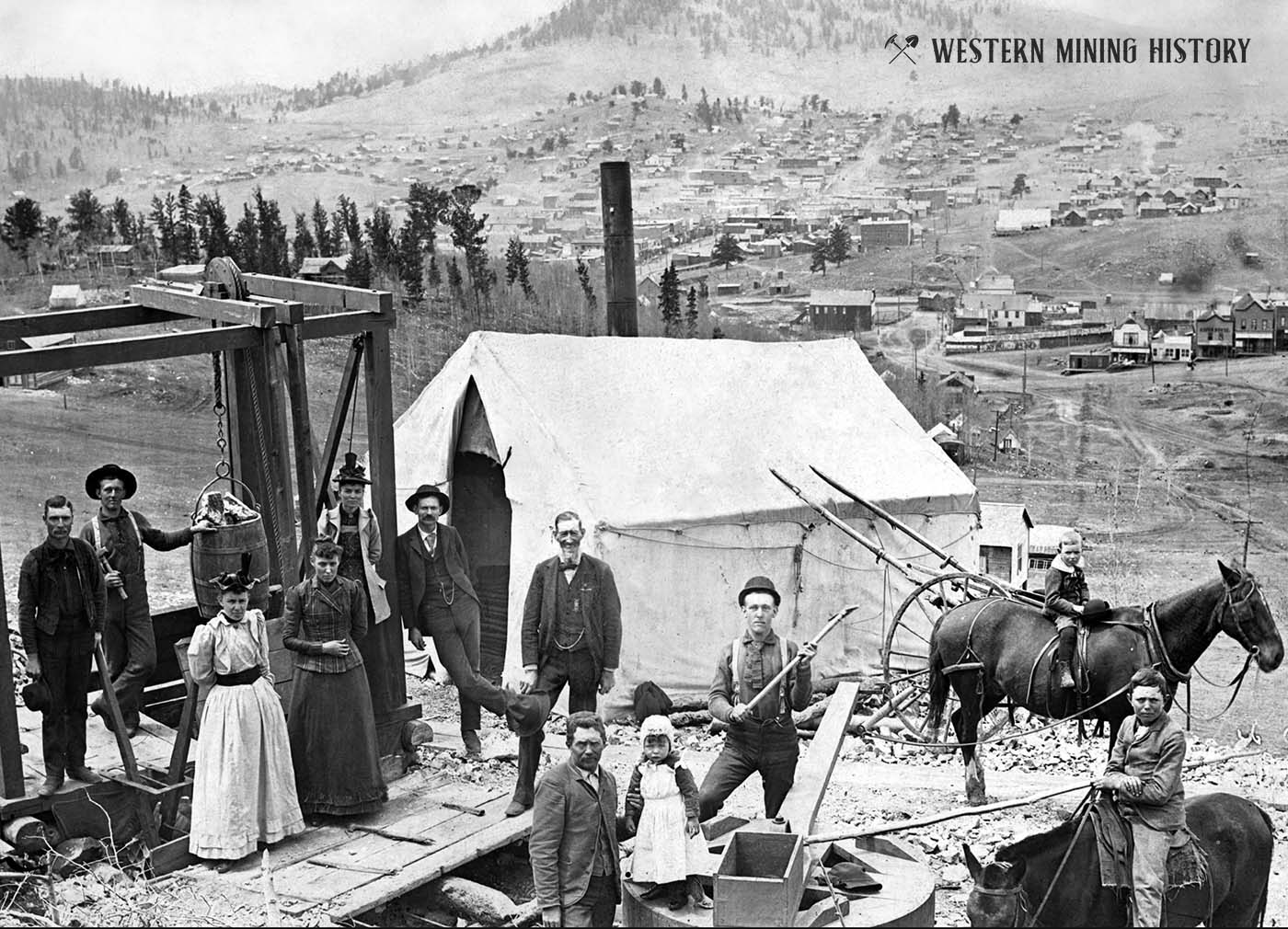

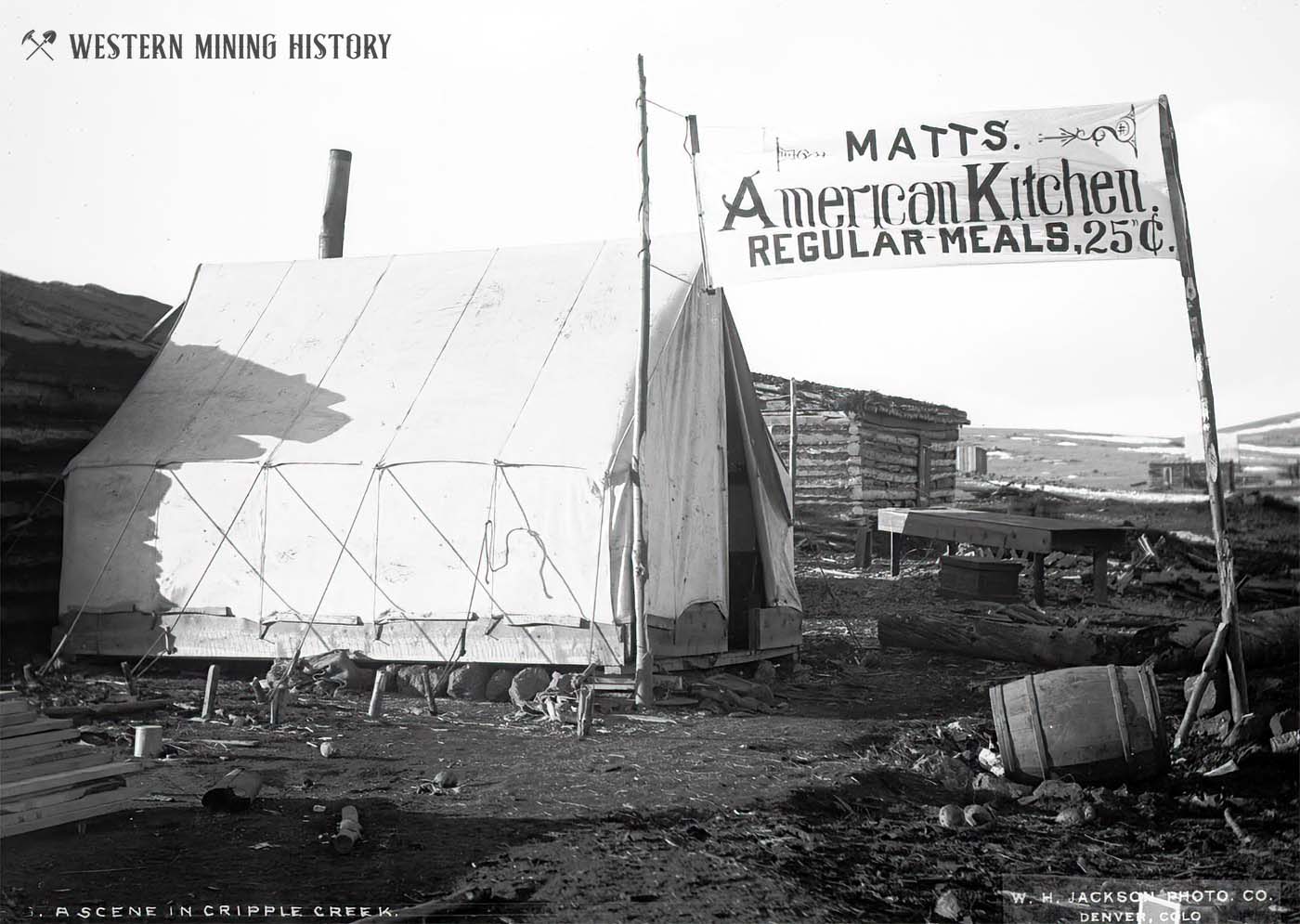

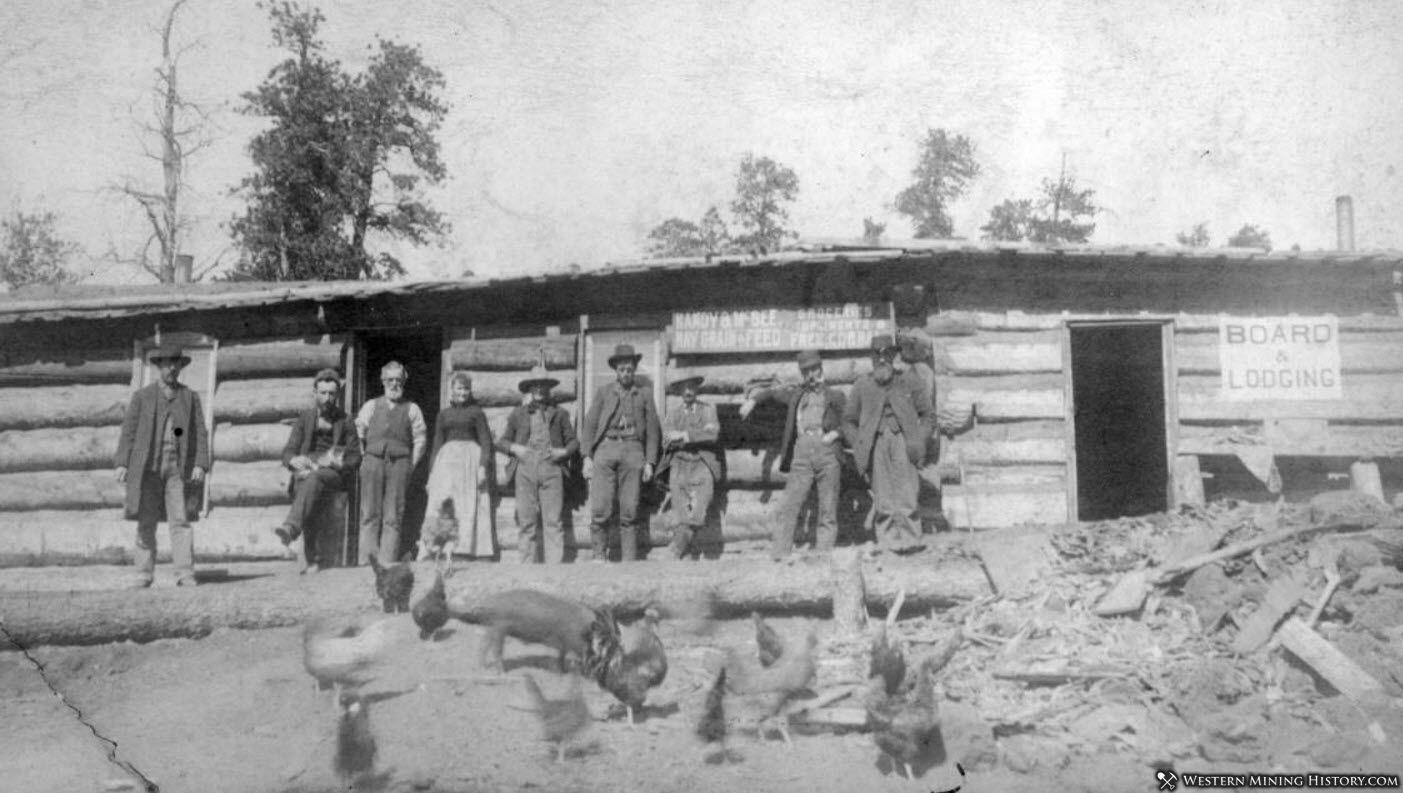

The town’s buildings were built hastily of wood frame or logs along the dirt streets; seas of tents sheltered businesses and many of the gold-seekers. One early name for the gold camp was Fremont, but the town became known as Cripple Creek. The name may be from cattle falling in the creek and injuring their legs, but nobody seems to know for sure. The town of Cripple Creek was formally incorporated in February 1892.

The main road in this era was a wagon road from Florissant; a stage coach connected the two by the fall of 1891. Cripple Creek was touted in local newspapers in 1892 as the “chance of a lifetime” and “not a health resort” but “a wealth resort” with “yellow gold found at grass roots and in the rock formation.” The town had about 6,000 residents by 1894.

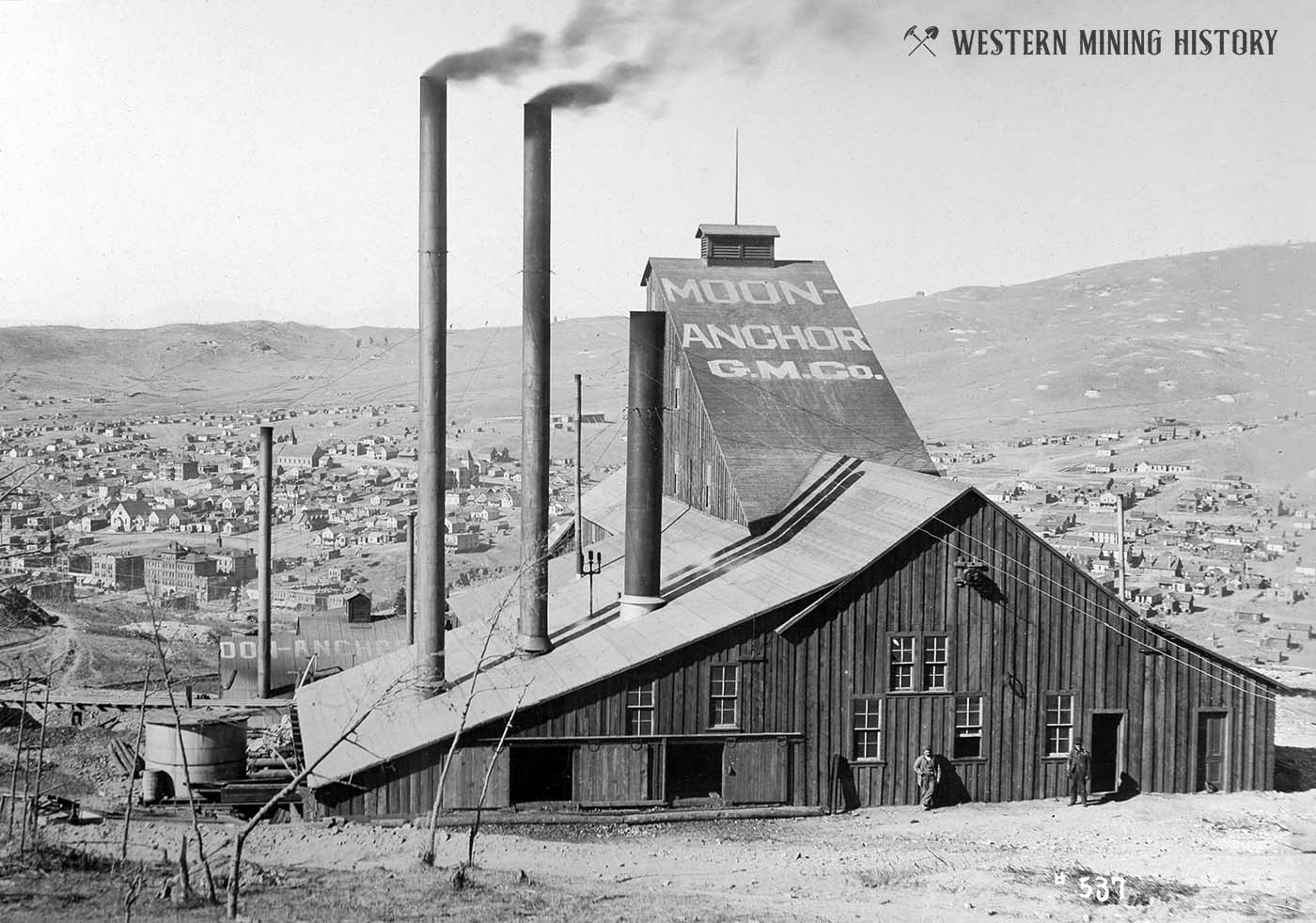

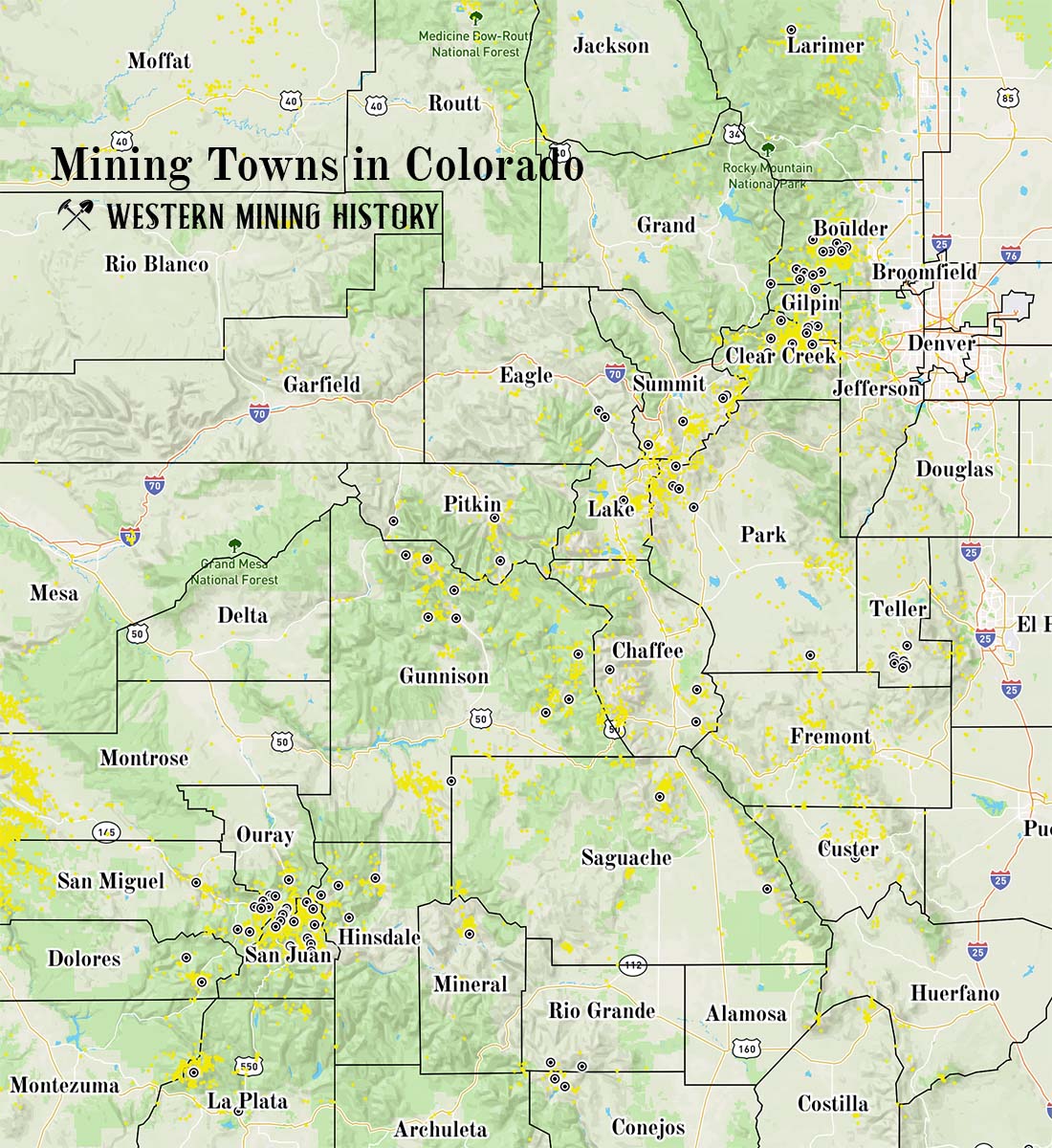

The town became part of the Cripple Creek Mining District, stretching for several miles east and south of Cripple Creek, including the smaller towns of Victor and Goldfield. Hundreds of mines in the district supplied a total of over 22 million ounces of gold in 25 years.

Welcome to Cripple Creek

A little girl named Mabel Barbee moved to Cripple Creek in 1892 when she was eight years old. Her prospector father couldn’t resist the call of gold when news spread about the strikes west of Pikes Peak.

She and her mother were sent from Utah to live with relatives in the Midwest while her father got settled in the new town. Finally, after trips by train and stage coach, the two were sandwiched like sardines in a coach drawn by six horses, just hours away from arriving in their new home.

The little girl was awakened by her mother and sleepily was led outside to stand in a line with the other stage coach riders. The stage had been struck by bandits, who moved down the line, confiscating valuables.

Mabel had been clutching a silver dollar and she was not going to let the outlaws find it in her pocket. But how could she keep them from discovering it? She faked a cough and sneakily pushed the coin from her fist into her mouth. The bandit seemed pretty amused after he got to Mabel, and she couldn’t figure out why. Then she realized her mouth was still open and the coin was visible!

The outlaw decided that he could afford to overlook this one coin. He took another silver dollar from his loot and placed that one in her mouth, too, laughing. Mabel wrote Cripple Creek Days, her memoirs of life in the town, in 1958.

Electric lights and telephone and telegraph lines reached the booming town in 1892. Two railroads competed to reach Cripple Creek first, with hundreds of men building the lines. The Midland Terminal Railway line connected Cripple Creek to Divide, to the north, by 1895.

A reduction mill was being built in Florence at the end of the Florence & Cripple Creek rail line, thirty miles to the south; this line won the race in 1894. The Colorado Springs & Cripple Creek District Railway (the Short Line) was built over the mountains, between the two towns in 1900.

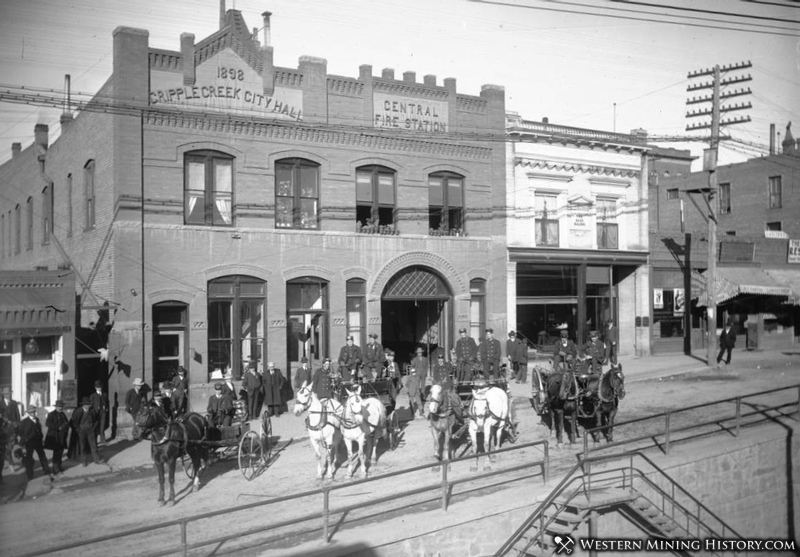

Two major fires devastated Cripple Creek in late April 1896, four days apart. The wooden buildings were no match for the blazes, even with a reservoir of water north of the town. The town was rebuilt mainly using brick to give some future protection from fire. Around 20,000 people lived in Cripple Creek before the fires, but many were left homeless and left on special trains to Colorado City.

In 1899, Stratton’s Independence mine near Victor was sold to a British group. He went on to buy a great amount of property in the Cripple Creek Mining District in 1900.

The southwestern corner of El Paso County, including the Cripple Creek Mining District, was separated into its own county in 1901. Cripple Creek became the county seat, and the Teller County Jail was built in 1901, now housing the Outlaws and Lawmen Jail Museum.

After 1900, gold production in the district tapered off, with temporary increases when a mine struck valuable ore. Population in the town - about 10,000 in 1900 - dropped over the next several decades.

Sam Strong was another of the men turned into millionaires by the Cripple Creek gold rush. He had staked out on early claim next to his friend from Colorado City, Winfield Stratton’s Independence Mine. He bought, sold, or leased out a number of successful mines and set up a money-loaning operation in Colorado Springs.

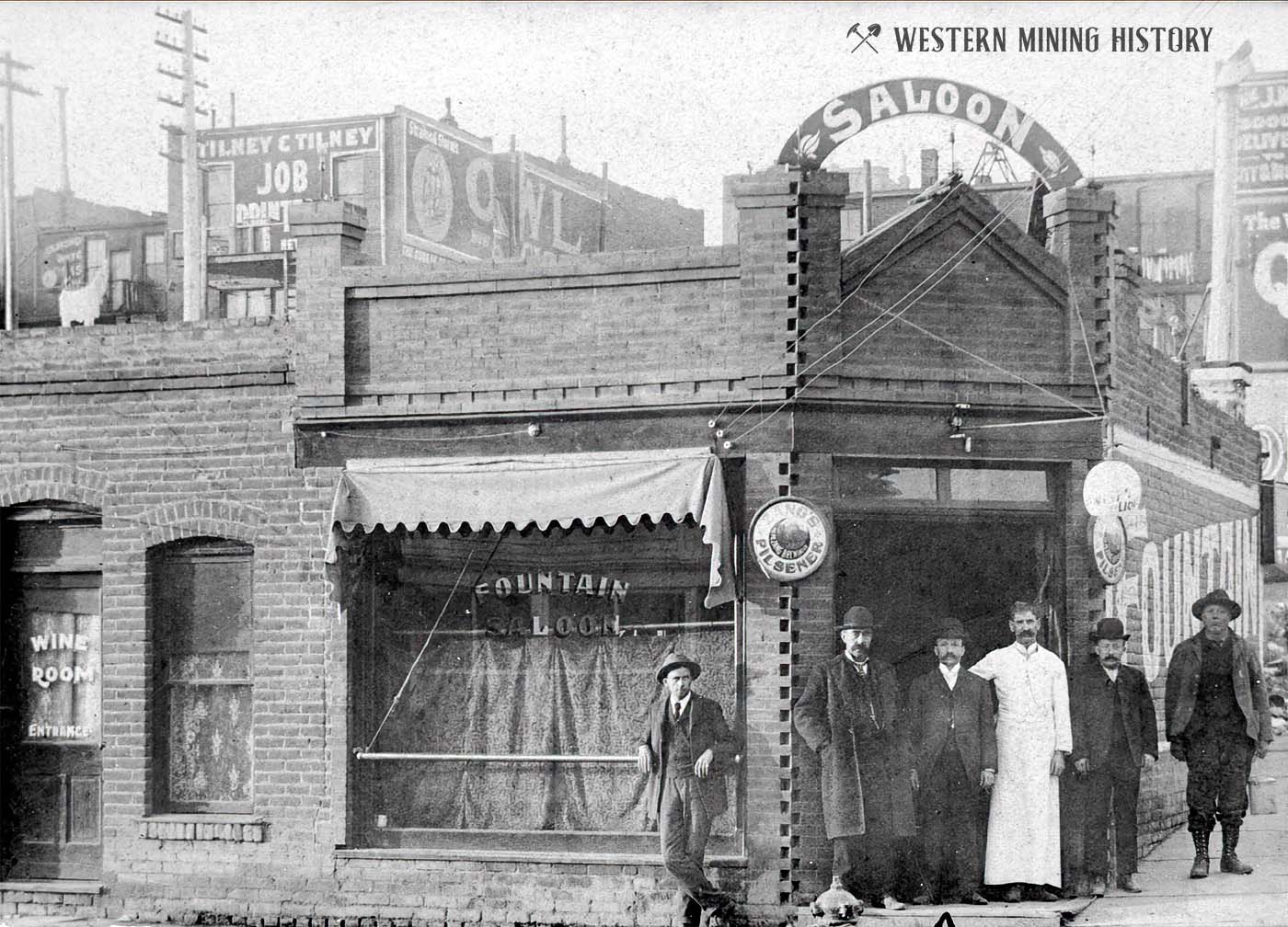

Sam was shot in a barroom brawl in the Newport Saloon in Cripple Creek in 1901 after a night of heavy drinking and gambling. The shooter, Grant Crumley, was co-owner of the bar and was accused of murder but pleaded self-defense and was later acquitted. The town doctor and mayor, F.J. Crane, soon banned the practice of carrying a concealed weapon (as gamblers often did) and banned gambling businesses as well.

Strong was notorious for his wild ways and was sued in 1901 by two ladies of the evening for abandoning them when he married a “respectable” woman. Nellie Lewis was awarded $50,000 in damages after a scandalous court case; Luella Vance’s claims were then settled out of court for the same amount.

Troubles in the Mines

Some of the local mine owners took advantage of a surplus of men looking for work early in 1894 and declared that the work day would be going up from eight to nine or ten hours, with no pay increase. Miners were given the option to keep the eight-hour day with a pay decrease of fifty cents a day.

A labor union, The Western Federation of Miners, called for a strike. Some mines closed and others were hit by explosions, including Strong’s mine. The miners who continued to work set aside ten percent of their wages to help the cause, and the union set up soup kitchens.

Local law enforcement either sided with the miners or wasn’t up to the task, and the governor sent in the state militia. After a year of unrest, negotiations ended up with the miners back to an eight-hour day with pay of three dollars for the day.

Another period of labor unrest shook up the local mining industry from 1903 to 1904. The Colorado National Guard was stationed at the mines by the governor, who declared martial law. Production was slashed in half, and fighting resulted in the deaths of a number of miners in the “Colorado Mining War”. Union miners were deported and organized labor was banned in the area.

The Myers Avenue Madams

Cripple Creek’s first madam, Blanche Burton, arrived in town in 1891 from Colorado City, soon followed by other enterprising ladies. The first brothels were in wooden shacks built along the town’s main street, Bennett Avenue, but later moved one street south, to Myers Avenue.

Cripple Creek soon offered four dance halls, eleven parlor houses, and twenty-six one-room “cribs.” Fines for prostitution in the early days of the town were only one dollar apiece annually for the ladies.

Prostitutes and madams flourished in Cripple Creek and numbered over 300 by 1896. The first of the two fires that nearly burned down all of the town’s businesses started in a brothel in 1896, when a lamp was kicked over. The Myers Avenue red light district was wiped off the map, but not for long, as bigger and better-made buildings went up.

One local madam, Pearl DeVere, rebuilt the Old Homestead parlor house on Myers Avenue offering the latest conveniences – electricity, a telephone, a bathroom, and running water. Pearl died of a morphine overdose in 1897 and her property was sold at auction.

Hazel Vernon, a madam, became the new owner of the Old Homestead in 1899. Vernon was listed as the proprietor in the 1902 Directory of the Cripple Creek District.

New ordinances against prostitution were passed in the early years of the twentieth century, and some establishments moved upstairs in buildings or created private membership clubs. New rules allowed the working girls one day per week that they could shop on Bennett Avenue, and they were prohibited from wearing skirts higher than six inches above their ankles.

Colorado enacted a law in 1915 making houses of prostitution illegal; it allowed for businesses to be raided and the building locked up for a year. An owner could have the building unlocked by promising not to allow prostitution there again. The Old Homestead Parlor House became a boarding house in 1917 and was turned into a brothel museum in 1958.

Gold mining made a comeback in the midst of the cash-strapped Great Depression era, when gold values soared. The 1930s was the only decade in the first seventy years of the twentieth century when the population of Cripple Creek increased. The federal government ordered gold mines closed during World War II as a non-essential industry; many mines never reopened.

The core of the historic town – both commercial and residential buildings – was declared a National Historical Landmark in 1961. The Cripple Creek Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

A building on East Bennett Avenue contained a family of five plus 23 roomers in 1910. The head of the house managed a restaurant. Some of the boarders – most of whom were male – also worked in a restaurant. Ten of the boarders were miners or machinists in mines. Their home was the Carr Building, a two-story brick structure built in 1896 and now containing fourteen hotel room suites. The main level commercial space probably contained the restaurant in 1910.

Home of the Donkey Derby and Legalized Gambling

To attract tourists, Cripple Creek created an event they called the Donkey Derby in the early 1930s. The tradition has been resurrected; the annual event features donkey races in the county fairgrounds. A world-class rodeo known as Top of the World and an ice festival with carved sculptures take place at Cripple Creek each year.

Colorado voters approved legalized, limited-stakes gambling for Cripple Creek in 1990. State and local historic preservation has benefited from some of the millions in annual tax proceeds, and many of the buildings built around the turn of the century have been adapted into casinos, hotels, and restaurants.

The population of Cripple Creek, which had dwindled to less than 200 before the vote, rebounded to 1,200 by 2010 as tourists hope to strike gold once again.

One mining operation is still active in the district – the Cripple Creek and Victor Gold Mine’s open pit mines have been uncovering silver and gold ore since 1994. The Mollie Kathleen Mine stopped production in 1994 and switched to offering tours of the underground mine. The tour lets you drop 1,000 feet below the ground and ride in a mine car.

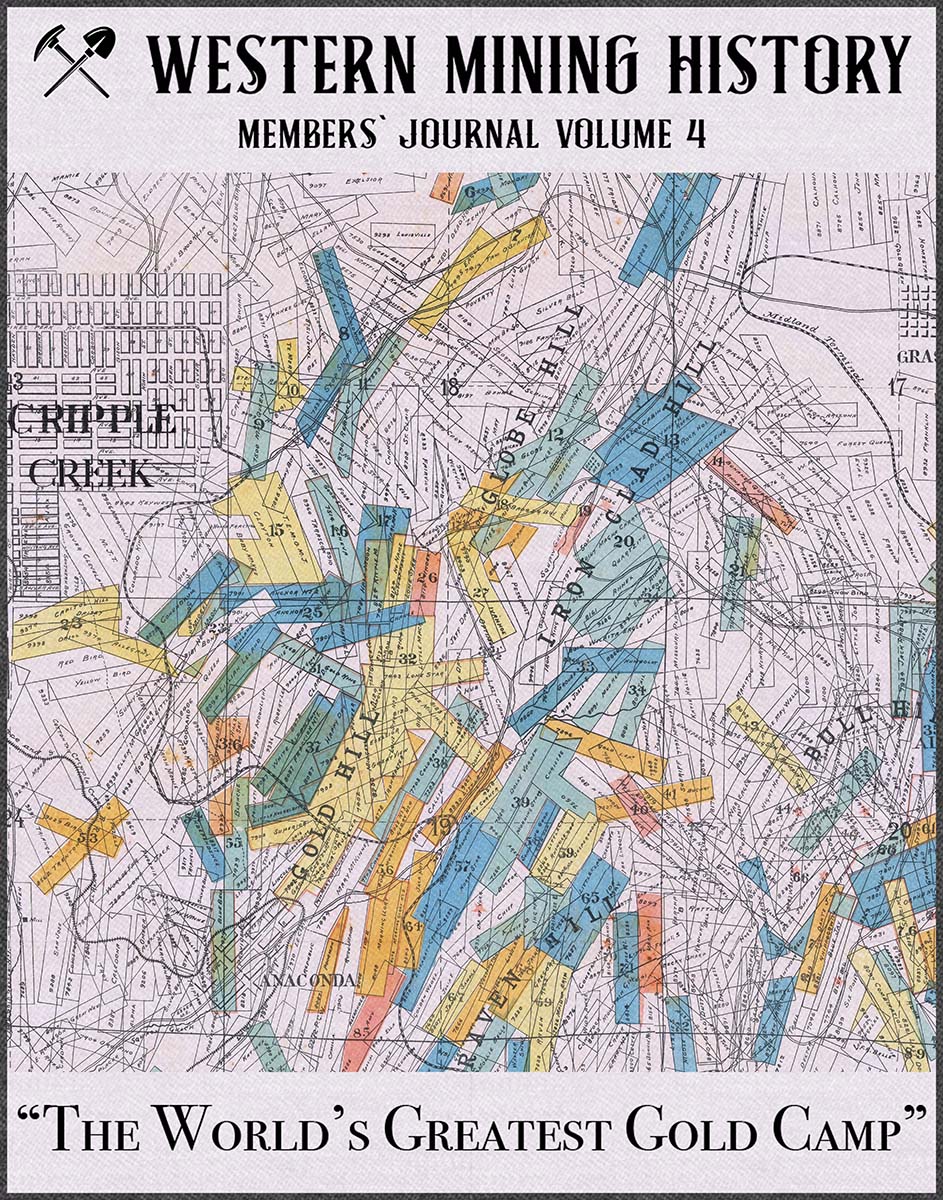

Cripple Creek “The World’s Greatest Gold Camp”

For members: "So thickly were the hillsides and gulches studded with homes, than one can easily say that the Cripple Creek district is one great city, covering thirty-six square miles." Cripple Creek – “The World’s Greatest Gold Camp” uses selected text from a 1903 special edition of the Cripple Creek Times, and over 50 images from various sources to illustrate the importance and magnitude of Cripple Creek during the district's peak years.

Bandits and Badmen: Crime in the Cripple Creek District

Within a few years of the 1890 gold discovery at Cripple Creek, the area had transformed into one of the world's fastest growing gold districts. Thieves, bandits and buncos were attracted to the towns of new district by the hundreds, and Cripple Creek became known for its lawlessness. Read more...

A Tour of Colorado Mining Towns

Explore over 100 Colorado mining towns: A tour of Colorado Mining Towns.

Colorado Mining Photos

More of Colorado's best historic mining photos: Incredible Photos of Colorado Mining Scenes.