By Jan MacKell Collins.

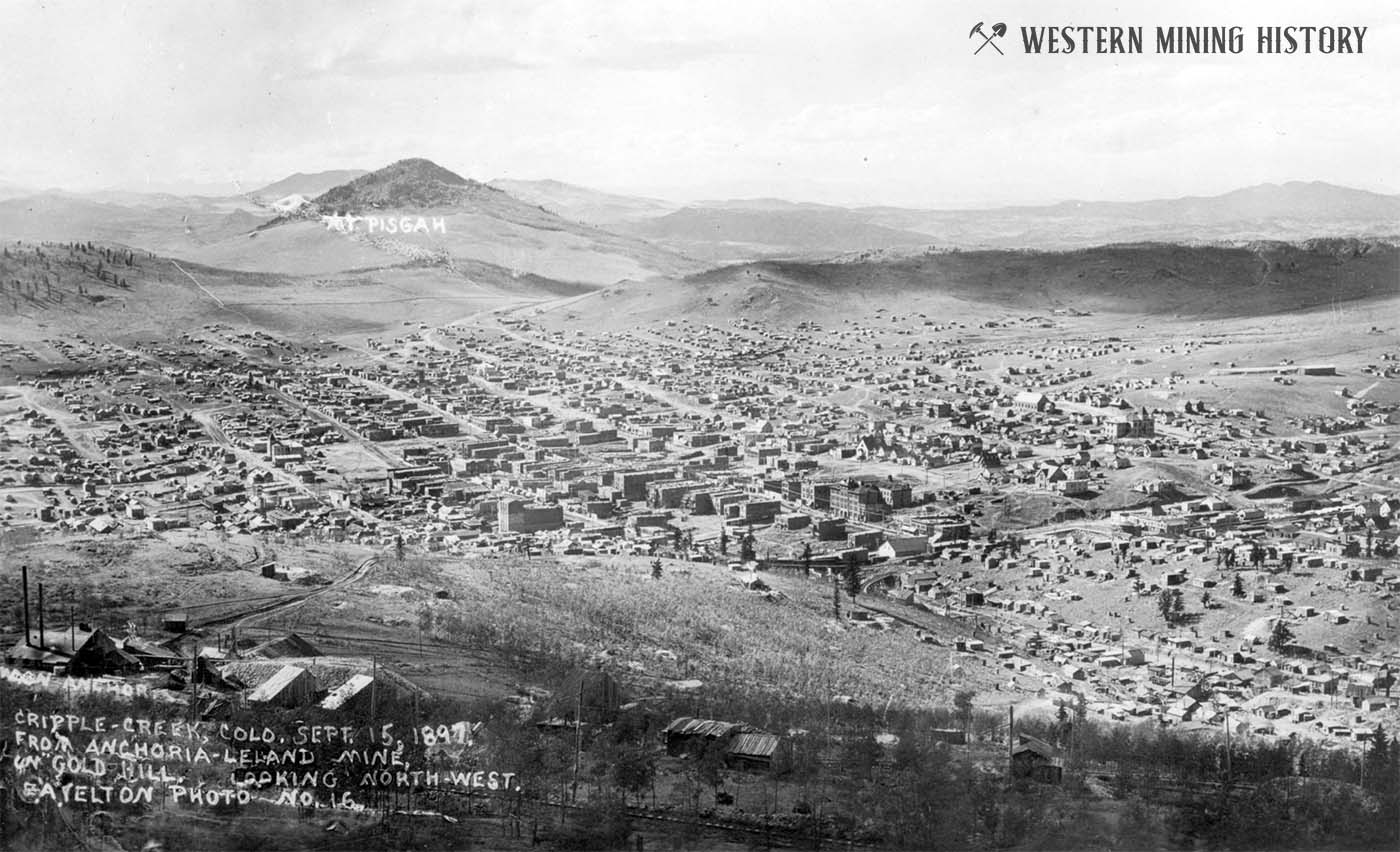

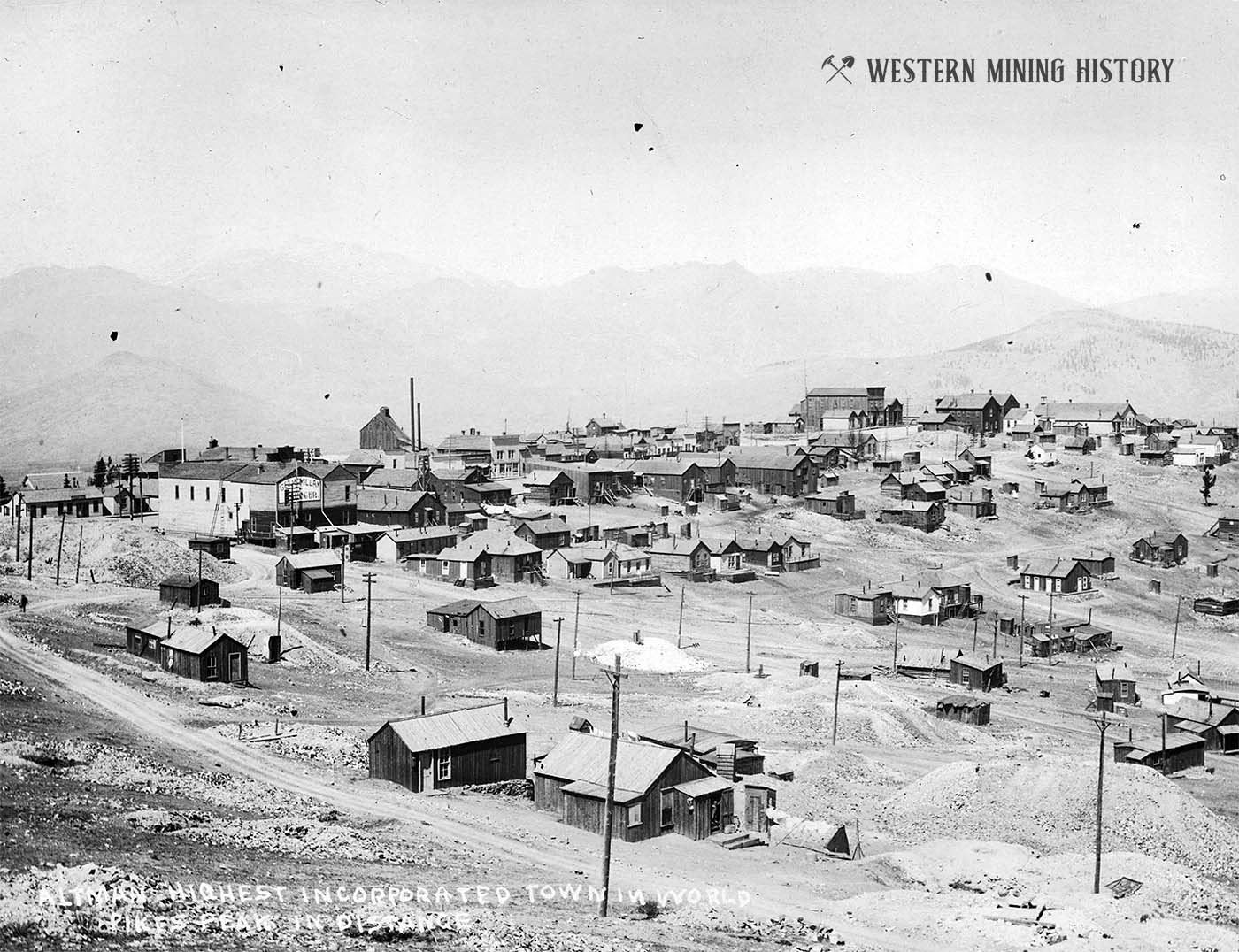

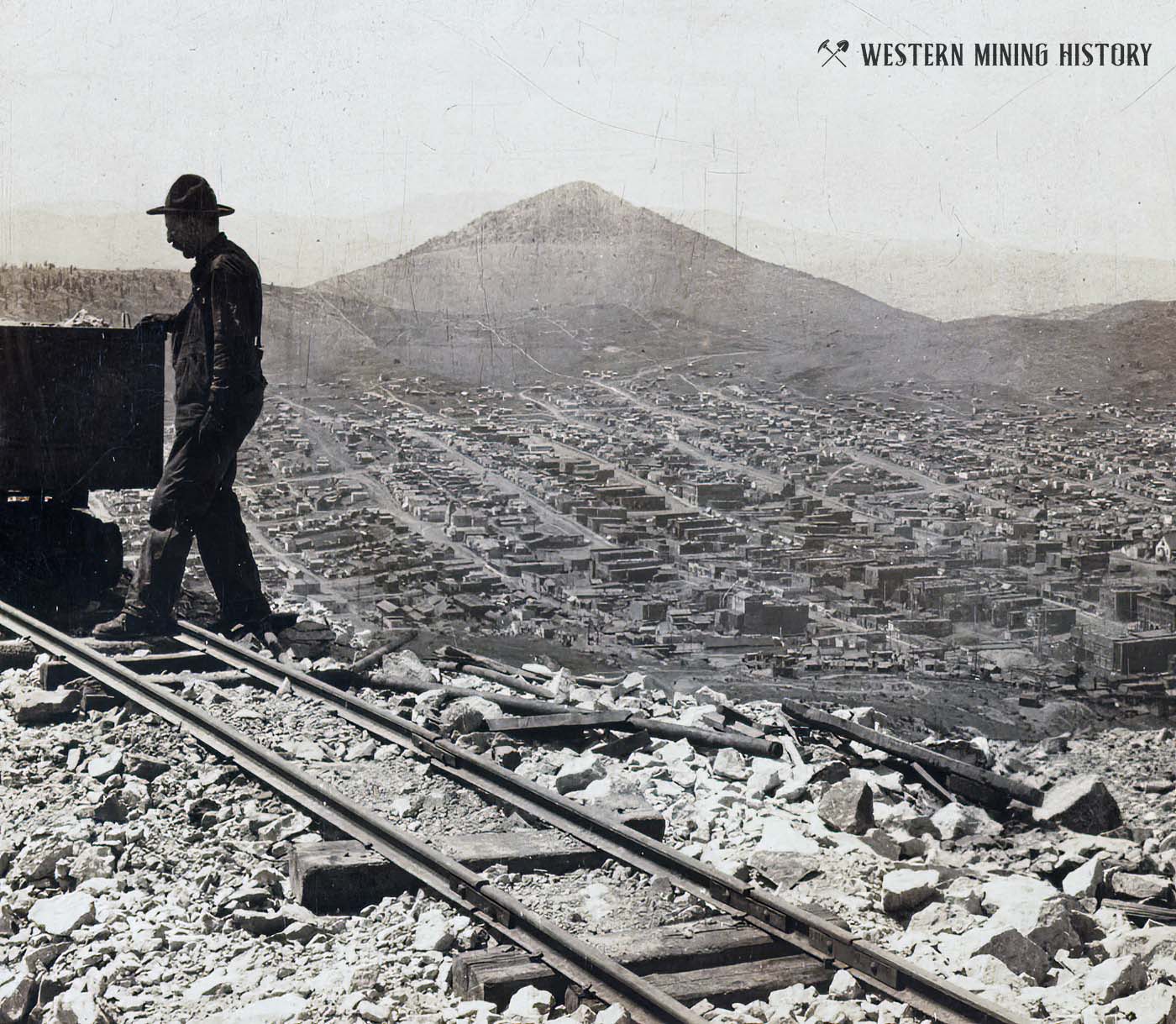

The last of Colorado’s great gold booms occurred in the Cripple Creek District, high on the backside of Pikes Peak, in 1891. Prior to that, the ranchers populating the area were hardly concerned with crime. The busy bustle of city life had yet to descend on the area.

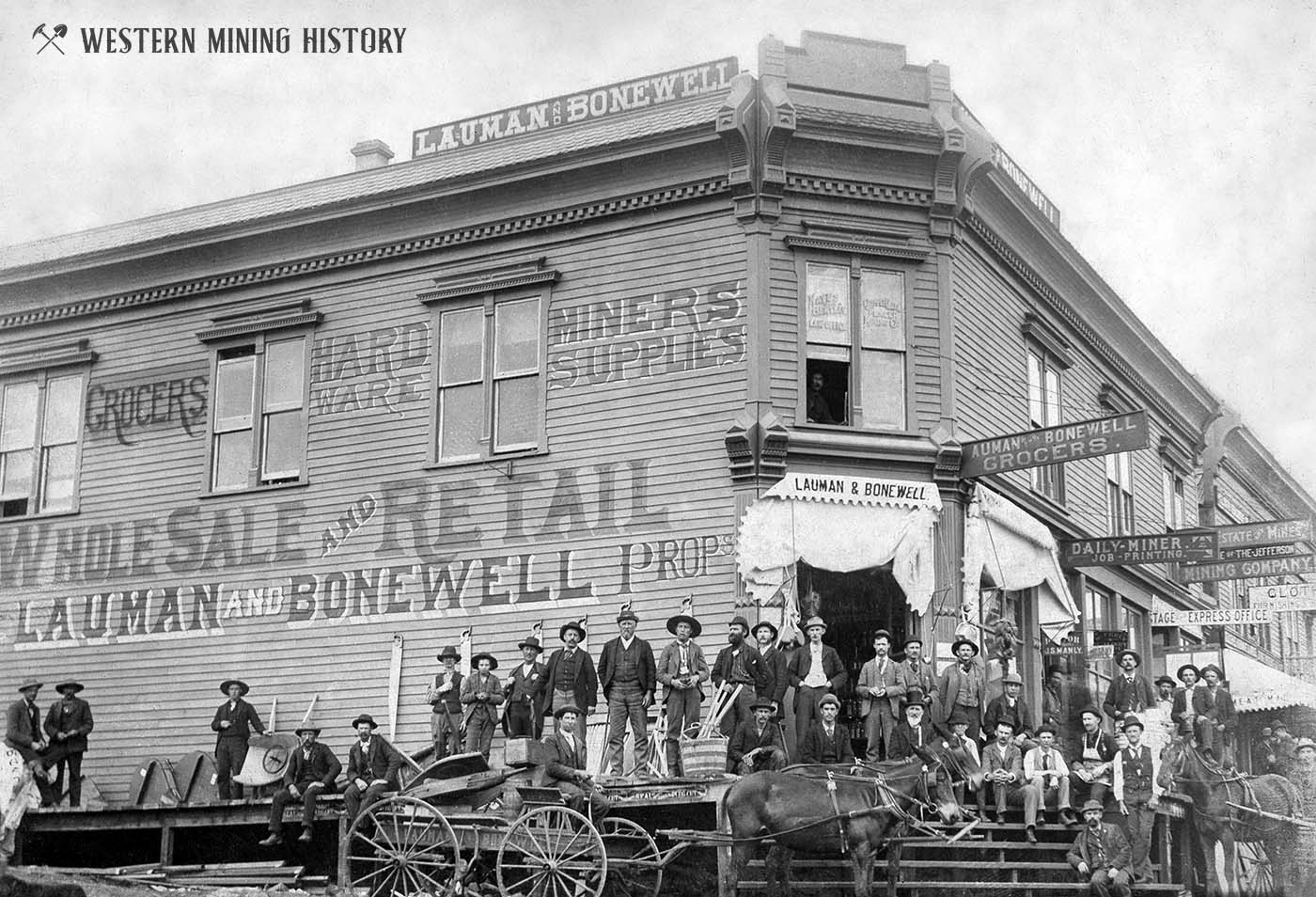

With the discovery of gold, however, the region’s status quickly turned from that of quiet cow camps and homesteads to several rollicking boomtowns within a short distance, each complete with the accompanying evils.

The growth of crime in the newly founded Cripple Creek District grew in proportion to the swelling population as prospectors, merchants, doctors, attorneys and a fair amount of miscreants descended upon the area. Marshal Henry Dana of Colorado Springs once joked that crime was down in his city because the law-breakers had all moved to Cripple Creek. He wasn’t far off.

Already, rumors had circulated for some time that the Dalton Gang of Kansas had used the area as an outlaw hideout. As the district grew, the Dalton’s moved on to their fateful end in Coffeyville, Kansas.

But for every outlaw who left the area, there was another one to take his place. Bunco artists, robbers, thieves and scammers soon descended upon the district in great numbers. The Cripple Creek District was still in its infancy and would lack proper law enforcement for some time.

Only after Cripple Creek ruffian Charles Hudspeth accidentally killed piano player Reuben Miller while attempting to shoot the bartender at the Ironclad Dance Hall did the city ban guns for a short time. But it was already too late. Cripple Creek’s outlaws were already blazing their own bloody path through history.

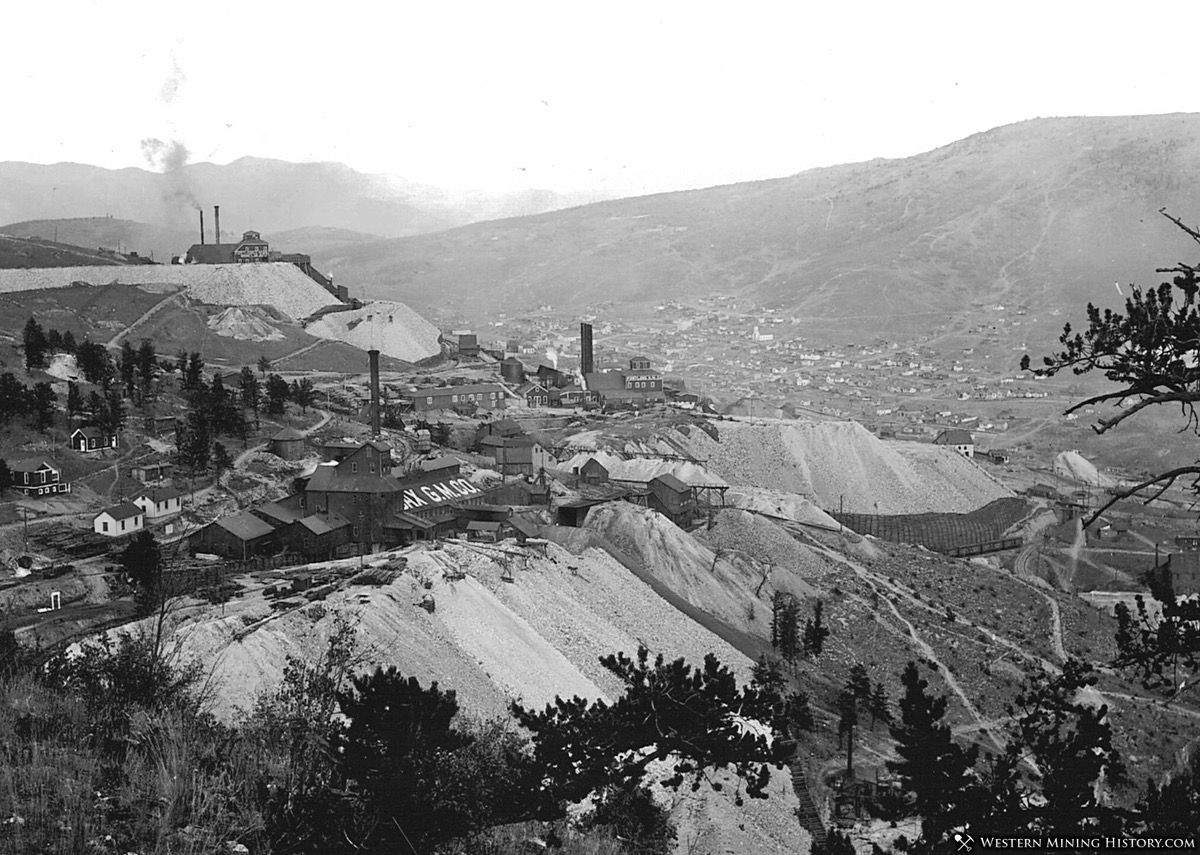

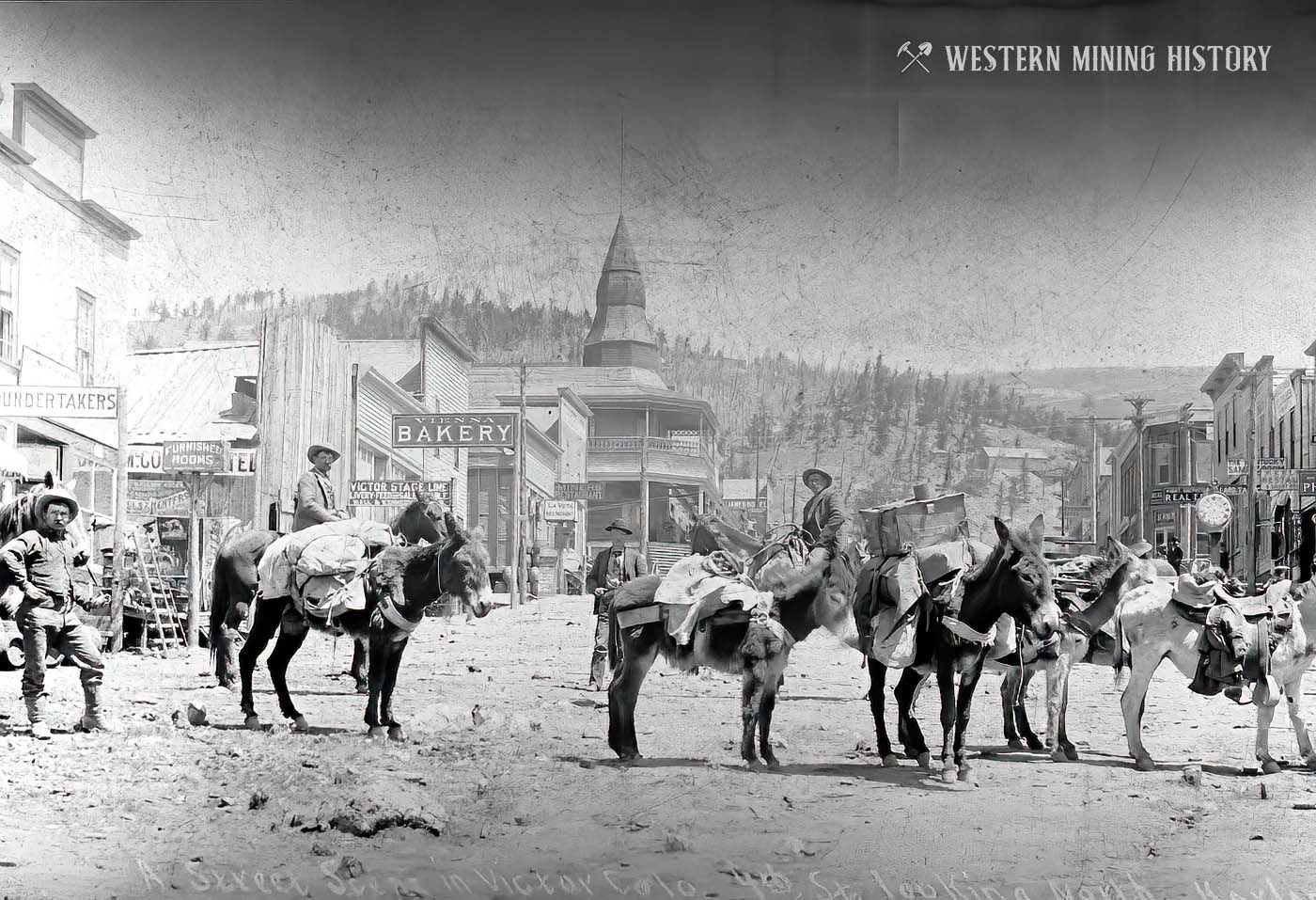

By 1894, gangs and undesirables were running rampant throughout the district. “Dynamite Shorty” McLain was one of the first bad guys to make the papers for blowing up the Strong Mine in the district city of Victor during labor strikes.

The Crumley Gang

There was a gang hanging around Victor too, headed by the Crumley brothers. Grant, Sherman and Newt Crumley, lately of Pueblo, found the pickings quite ripe and soon fell in with outlaw Bob Taylor and his sister Nell, Mrs. Hailie Miller, Kid Wallace and O.C. Wilder.

Sherman Crumley was especially susceptible to running with would-be robbers. In May of 1895, he and Kid Wallace were arrested after five armed men robbed the newly formed Florence and Cripple Creek Railroad. Apparently a “toady” named Louis Vanneck squealed after receiving less than his share of the loot, which primarily consisted of money taken from passengers. Wallace went to jail, but the popular Crumley was acquitted.

Following the incident, the Crumley gang contented themselves with cheating at poker and rolling gamblers in the alleys. Sherman was also a known thief, often stashing his loot in abandoned buildings around smaller communities like Spring Creek just over Mineral Hill from Cripple Creek.

The Crumleys remained in the Cripple Creek District for some time, until Grant shot mining millionaire Sam Strong to death at the Newport Saloon in Cripple Creek in 1902. Grant was not without good reason, for Strong had suddenly pulled a gun on him and accused him of running a crooked roulette wheel.

Still, the killing of a man was not a reputation the Crumley’s wished to sustain, and the threesome quickly moved on to Tonopah and Goldfield, Nevada. Grant quickly earned a fine reputation as a man about town, while Newt became quite respectable and even owned the fabulous, four-story Goldfield Hotel for a time. His son, Newt Jr., would become a state senator.

“General” Jack Smith

The activities of the Crumleys were actually quite minor compared to those of “General” Jack Smith and his followers at the district town of Altman. Miner, poet and Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph columnist Rufus Porter (aka the “Hard Rock Poet”) once wrote a ballad about the town’s first marshal, Mike McKinnon. The honorable lawman died following a gunfight with six Texans (but not, allegedly, before he killed all six outlaws).

Porter may have actually been recalling an incident from May 1895, when outlaw General Jack Smith dueled it out with Marshal Jack Kelley. Smith had been running amuck for some time and had been warned by Kelley to stop trying “to run the town in his usual style.” On May 14, Smith wrapped up a night of drinking by shooting the locks off the Altman jail, thereby freeing two of his buddies, who were already incarcerated for drunkenness.

Smith wisely left town, but the next day, a constable named Lupton and one Frank Vanneck located him in a Victor saloon. “I want you, Jack,” Lupton said, to which Smith replied, “If you want me, then read your warrant.” Lupton began reading the warrant, but Smith appeared to go for his gun. The constable quickly pinned the outlaw’s arms while Vanneck shoved a gun to Smith’s chest. Smith was arrested with a bond of $300.

He managed to pay the bond quickly, however, and was next seen riding toward Altman “with the open declaration of doing up the marshal who swore the complaint.” Altman authorities were notified as Lupton and Victor deputy sheriff Benton headed for the town. By then, Smith had already gathered a small force of men, including one named George Popst.

The bunch headed to Gavin and Toohey’s Saloon, where Smith started ordering one drink after another. Outside, Lupton and Benton met up with Marshal Kelley and set out in search of the General. Kelley “had just lifted the latch of Lavine and Touhey’s [sic] saloon, when ‘crack’ went a gun from the inside. The ball struck the latch and glanced off.” Kelley threw the door open and shot Smith just below the heart. From the floor, Smith fired and emptied his own gun as Kelley continued shooting him.

Outside, Benton fired a shot through the window that hit Popst. “The latter may recover,” predicted the newspaper, “but Smith is certain to die.” Popst also died, about a week later.

Shootings and Robberies

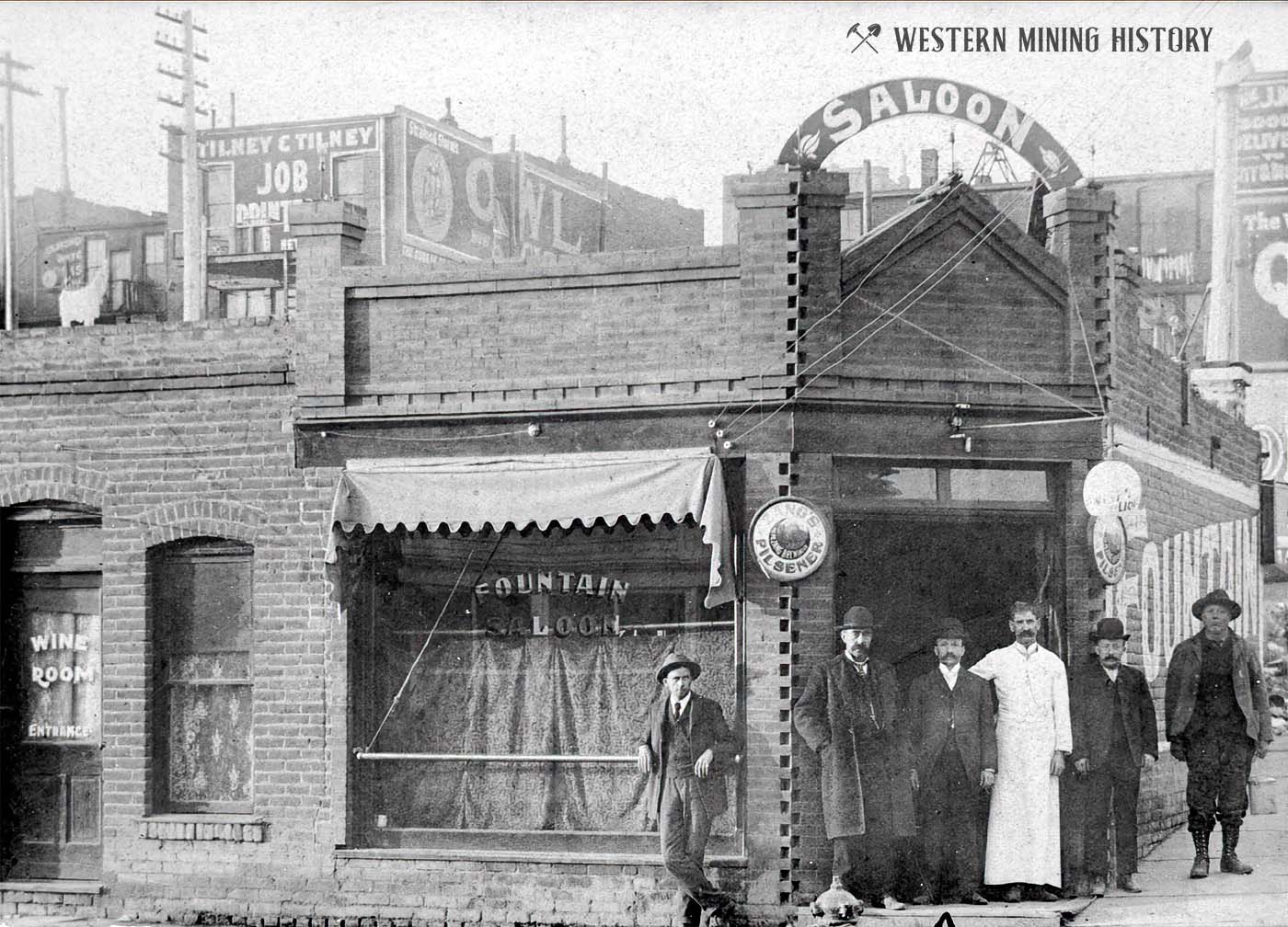

Saloon shootings in the Cripple Creek District occurred with such frequency that sometimes, they were hardly regarded as newsworthy. An 1895 article in the Colorado Springs Gazette reported half-heartedly that Joe Hertz, a.k.a. Tiger Alley Joe, was shot above the Denver Beer Hall in Cripple Creek by Clem Schmidt. Hertz staggered down to the bar exclaiming, “That crazy Dutchman shot me!” A few minutes later, he fell to the floor and died.

The Gazette neglected to follow up on the crime or make comment on its effect in Cripple Creek. The year 1896 did not prove much better for the lawmen of the district. General Jack Smith’s widow, a prostitute known as “Hook and Ladder Kate,” masterminded the robbery of a stagecoach outside of Victor. In early April, Coroner Marlowe was contending with the likes of J.S. Schoklin, who dropped his loaded gun in a saloon and subsequently fatally shot himself in the side.

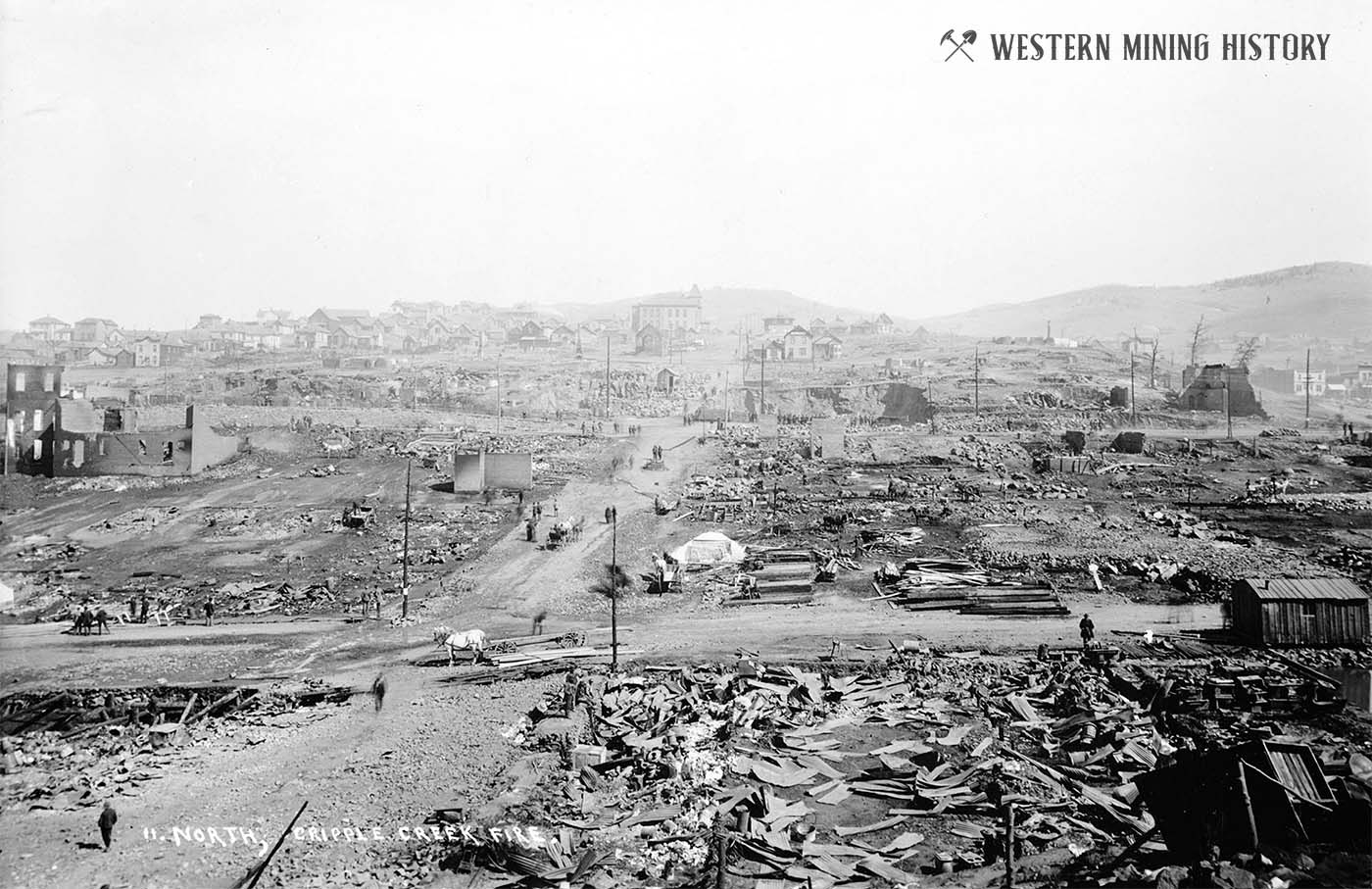

On April 25 and again on April 29 of the year 1896, Cripple Creek suffered two devastating fires that sent residents into a full blown panic as much of the downtown area and hundreds of homes burned. Folks hurried to rescue what they could in the wake of the flames.

Thousands of goods and pieces of furniture were piled high in the streets. It was prime picking for looters and arsonists, the latter whom set even more fires to instill further panic so they could rob and steal. In response, firemen, police and good Samaritans beat, clubbed or shot the law-breakers as a way to restore order.

Petty crimes and robberies continued intermittently for the next few years, and brawls and gunfights were common throughout the district. Crimes increased dramatically when the Cripple Creek District rallied against Colorado Springs to form Teller County in 1899. El Paso County clearly did not want to lose its lucrative tax base from the rich mines of the district.

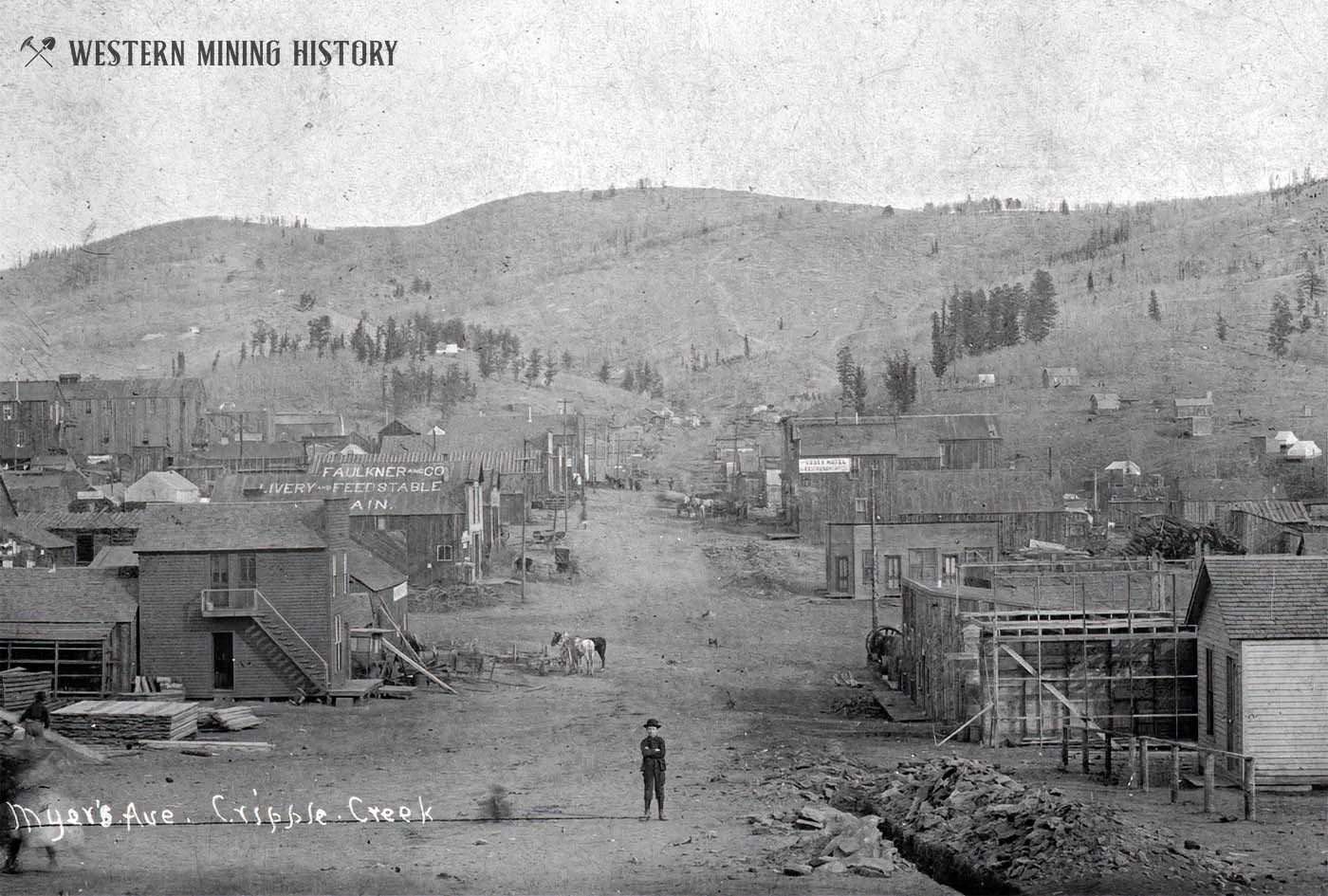

Arguments over the matter turned into all-out screaming matches, fights, and shootings. Thus the newly formed county, with Cripple Creek as the county seat, found itself besieged with lawlessness, free-for-all fights in the saloons along Myers Avenue, and high-grading of gold which was so widespread it was hardly thought illegal.

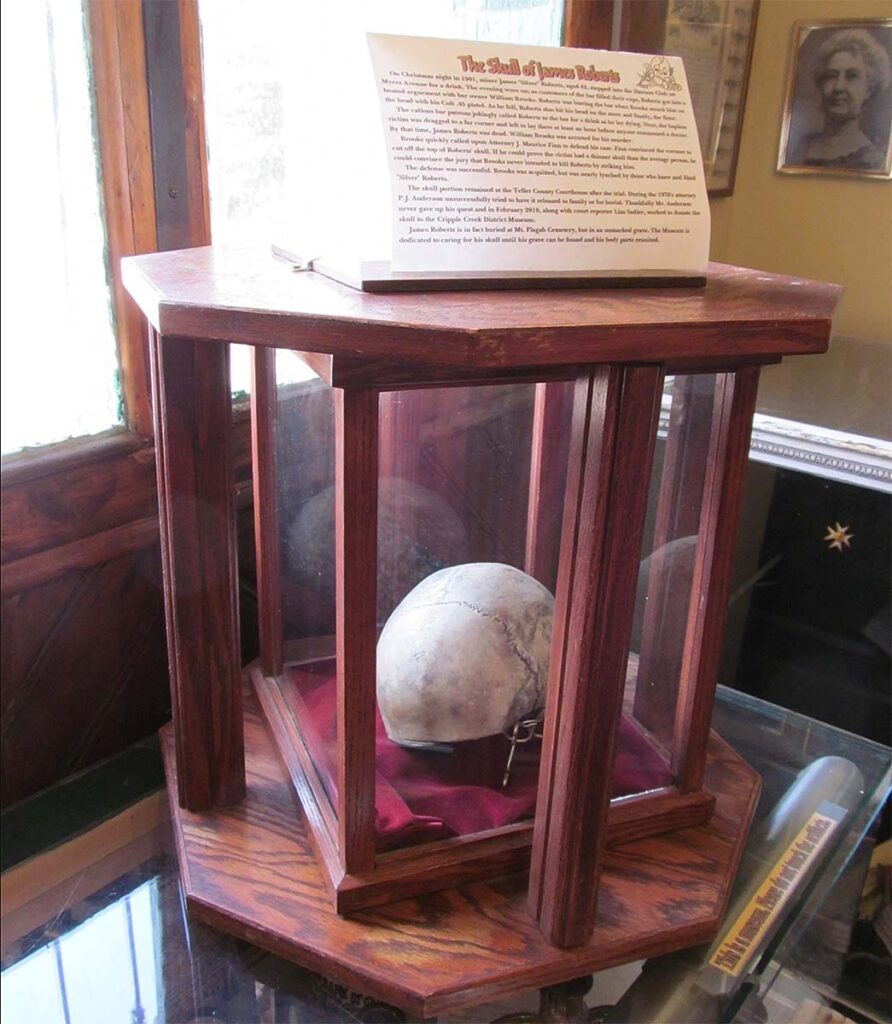

For several more years, law enforcement continued grappling with the outlaw elements around the district. Incidents making the papers included the death of James Roberts, who was clubbed with a gun and left to die on the floor of the Dawson Club as other patrons urged him to the bar for a drink (a portion of Roberts’ skull, used in testimony against his killer, is on display at the Cripple Creek District Museum).

Myers Avenue

Down in Cripple Creek’s infamous red-light district on Myers Avenue, prostitute Nell Worley was arrested for shooting at a man breaking down her front door. Nell was arrested because the bullet missed its mark and hit a musician on the way home from the Grand Opera House instead. Luckily he was only injured.

Indeed, Myers Avenue was peppered with illegal gamblers, pick pockets and drunks who felt free to wave and fire their guns at will. The red-light district spanned a full two blocks, offering everything from dance halls to cribs, from brothels above saloons to elite parlor houses.

Crimes, suicides, death from disease and frequent scuffles were the norm on Myers Avenue, where anything could happen – and eventually did. Today, Madam Pearl DeVere remains the best-known madam in Cripple Creek, and her fancy parlor house, the Old Homestead, remains one of the most unique museums in the west.

Theodore Roosevelt

Vice-presidential nominee Theodore Roosevelt visited Victor in 1900. Political tensions were high, and Roosevelt was attacked by an angry mob of protesters as he disembarked from the train. Cripple Creek postmaster Danny Sullivan is credited with keeping the crowd at bay with a two by four until Roosevelt was back on the train.

A year later Roosevelt visited again, then as Vice President. This time he was treated with much more respect, although the apologetic city council of Victor kept him entertained for so long that he barely had time to visit Cripple Creek before departing.

More Labor Trouble

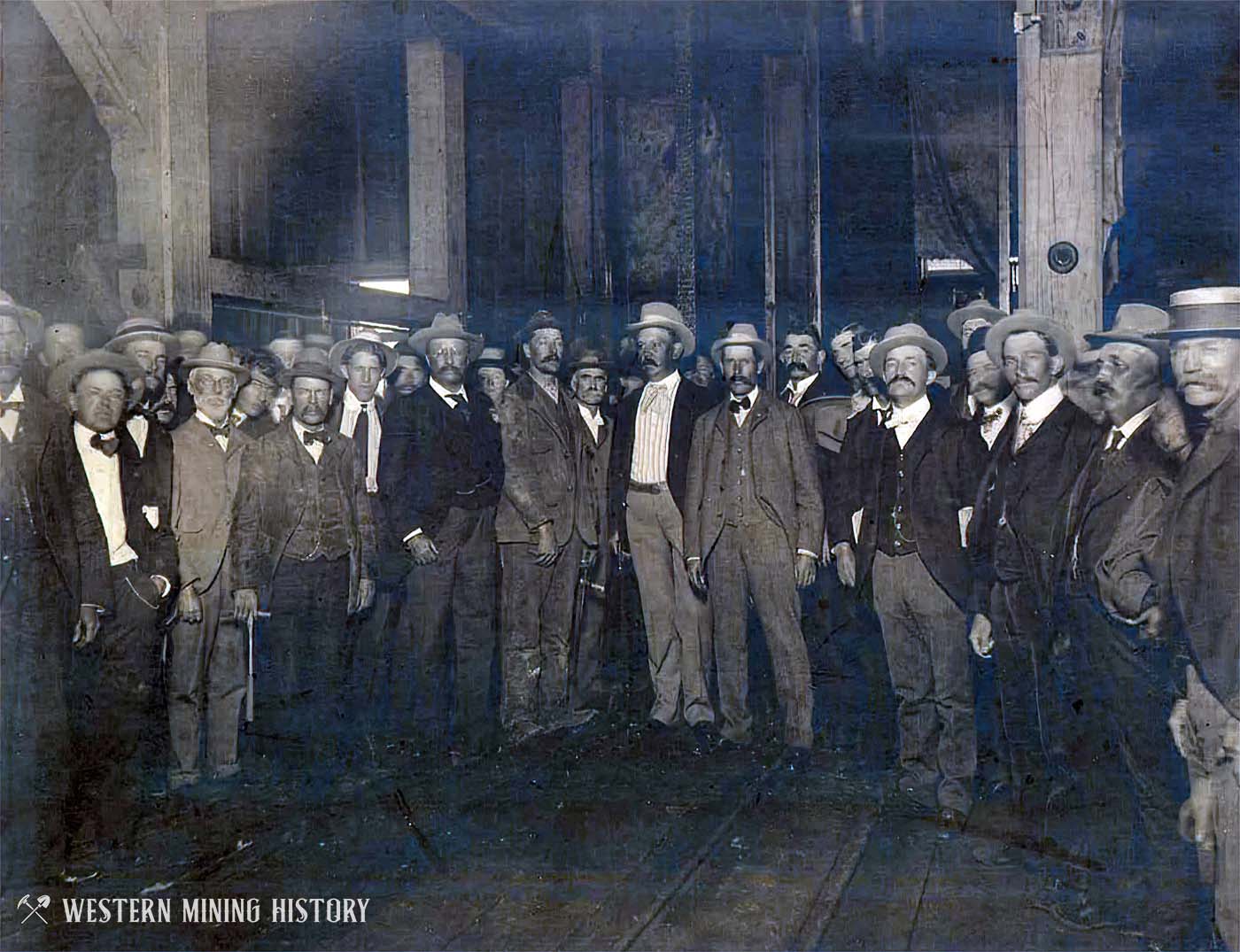

When labor strikes reared their ugly head once again in 1903, citizens of the district found themselves pitted against each other. Union and non-union miners fought against one another. Neighbors stopped speaking to each other. Down in the schoolyards, even children fought on the playground over a debate they actually knew little about.

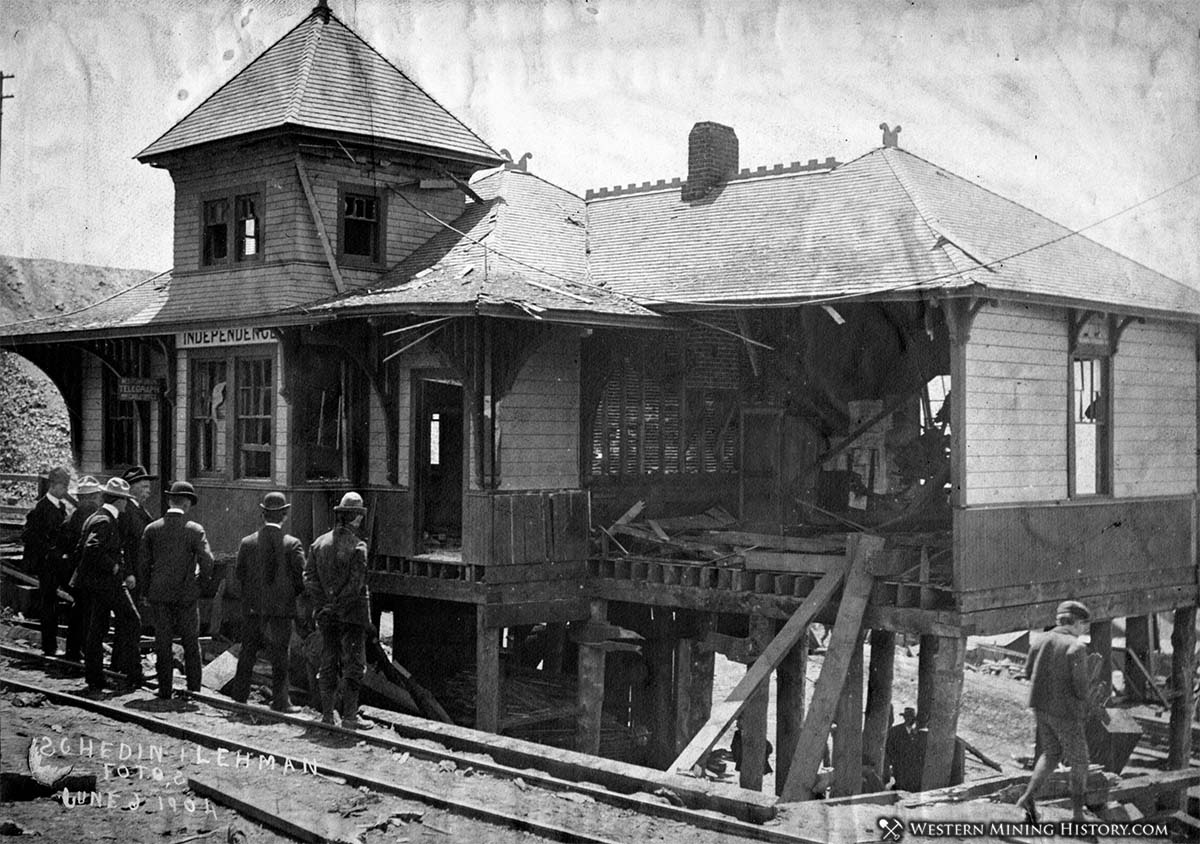

Soon, miners were being jailed and/or deported from the district, and one time the entire staff of the Victor Record newspaper was arrested for publishing an unpopular editorial. Things reached a head when professional assassin Harry Orchard set off a bomb at the Vindicator Mine and blew up the train depot at the district town of Independence.

During a heated election debate in the district town of Goldfield, deputy sheriff James Warford was hired to oversee the elections. According to Warford, Goldfield constables Isaac Leibo and Chris Miller were shot in self defense when they refused to “move on.” An examination of the bodies, however, revealed both were shot from behind.

Eight years later, long after the strikes had been settled, Warford was found beaten and shot to death on nearby Battle Mountain. His murder was never solved.

End of an Era

Eventually the Cripple Creek District’s mines began to decline from their peak years, and folks slowly began moving away. The sharks and scheisters moved on too, in search of fresh pigeons to pluck. It would be many more decades before legalized gambling would find its way to Cripple Creek, bringing a whole new, modern generation of eager residents, as well as the accompanying crimes.

For history buffs, there are still some mysteries remaining in the district yet. In Mt. Pisgah Cemetery at Cripple Creek, a wooden grave marker was once documented as reading, “He called Bill Smith a Liar.” Urban legend has it that after gambling was legalized, renovations of Johnny Nolon’s original casino in Cripple Creek revealed a body in a strange shaft under the building.

During the excavation of an outhouse pit at the ghost town of Mound City during the 1990s, remains of a perhaps quickly discarded revolver were found. These and other mysterious remnants still surface now and then, to remind us of the many other crimes the lively Cripple Creek District once witnessed.

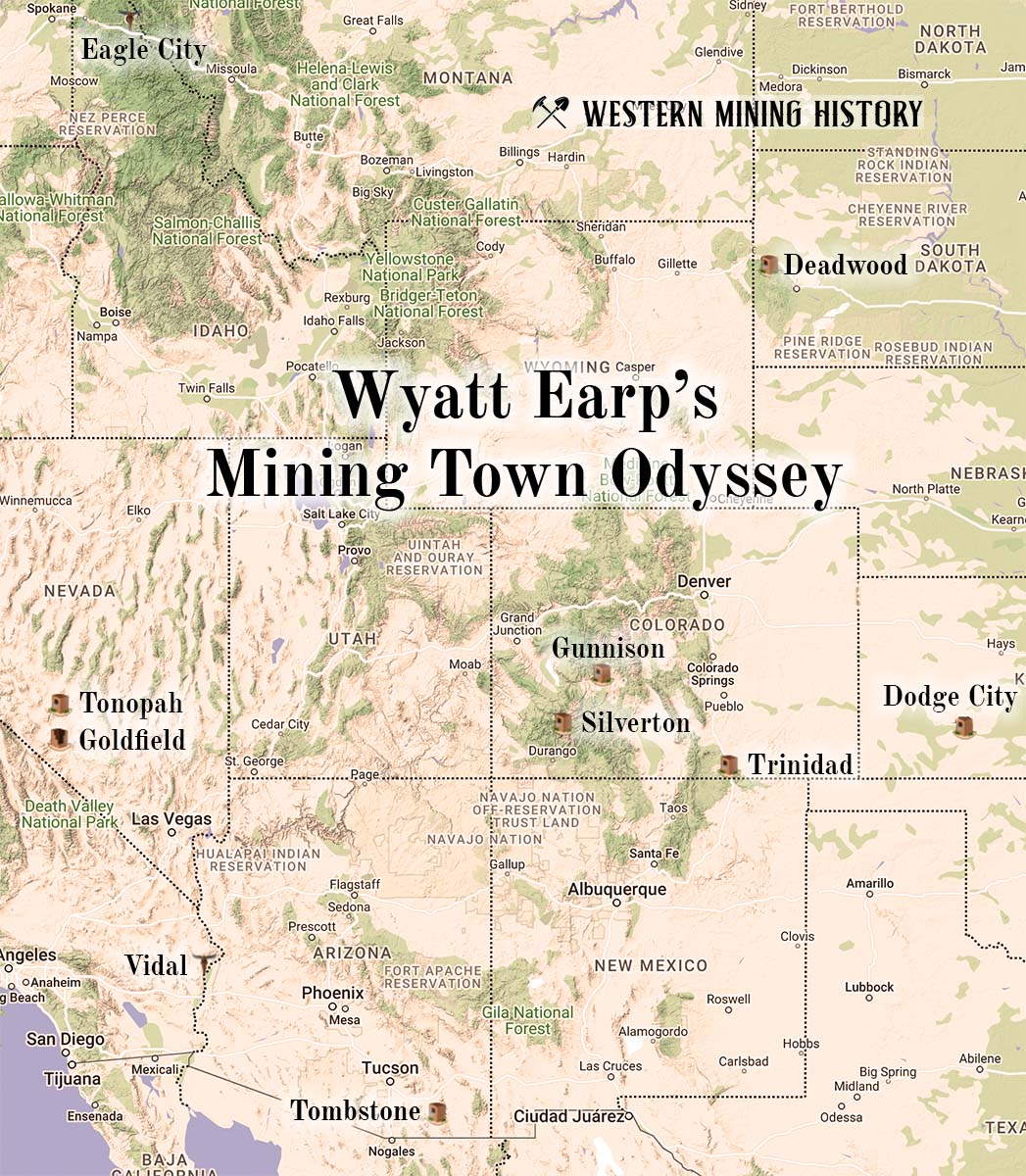

Wyatt Earp: A Mining Town Odyssey

Wyatt Earp spent most of his adult life moving between numerous gold rushes and mining excitements. In 1905 a newspaper described his wanderlust: “wherever was a new gold camp, a new oil field, a new place in which money was plentiful, there could be found Wyatt Earp, quiet, careful, but deadly in his own defense.” Read more…