Bisbee History

In the 1870s, the Arizona Territory was a vast and sparsely populated area that was hostile in terms of weather, terrain, and the natives that had called the area home for centuries.

Mineral development in the region had proceeded slowly since the 1860s, and often rich strikes were abandoned due to hostilities with the fierce Apache tribes, not to be rediscovered until many years later.

These circumstances resulted in prospectors often working in conjunction with the military, and sometimes it was the troops themselves that made the discoveries. This was the case with the initial discoveries in the Mule Mountains of southeast Arizona that would later be the site of the great copper camp of Bisbee.

In 1877, members of an Army search party from Fort Bowie staked the first claim in what would be known as the Warren district. The initial settlement was called Mule Gulch, and the focus of the miners at that time was gold and silver.

The area was too remote to develop and transport copper ore, and nationwide demand for copper was not yet strong enough to warrant large investments in remote copper mines.

That situation would change rapidly however as electrification would begin sweeping the nation in the early 1880s and Arizona mine owners wanted to be ready to meet the demand. In August of 1880 the Copper Queen Mine was capitalized for $2.5 million dollars.

The Mule Gulch camp was renamed Bisbee after DeWitt Bisbee, a San Francisco attorney and one of the Copper Queen investors. Mr. Bisbee is said to have never made the trip to see his namesake town.

Bisbee Rises as a Great Copper Camp

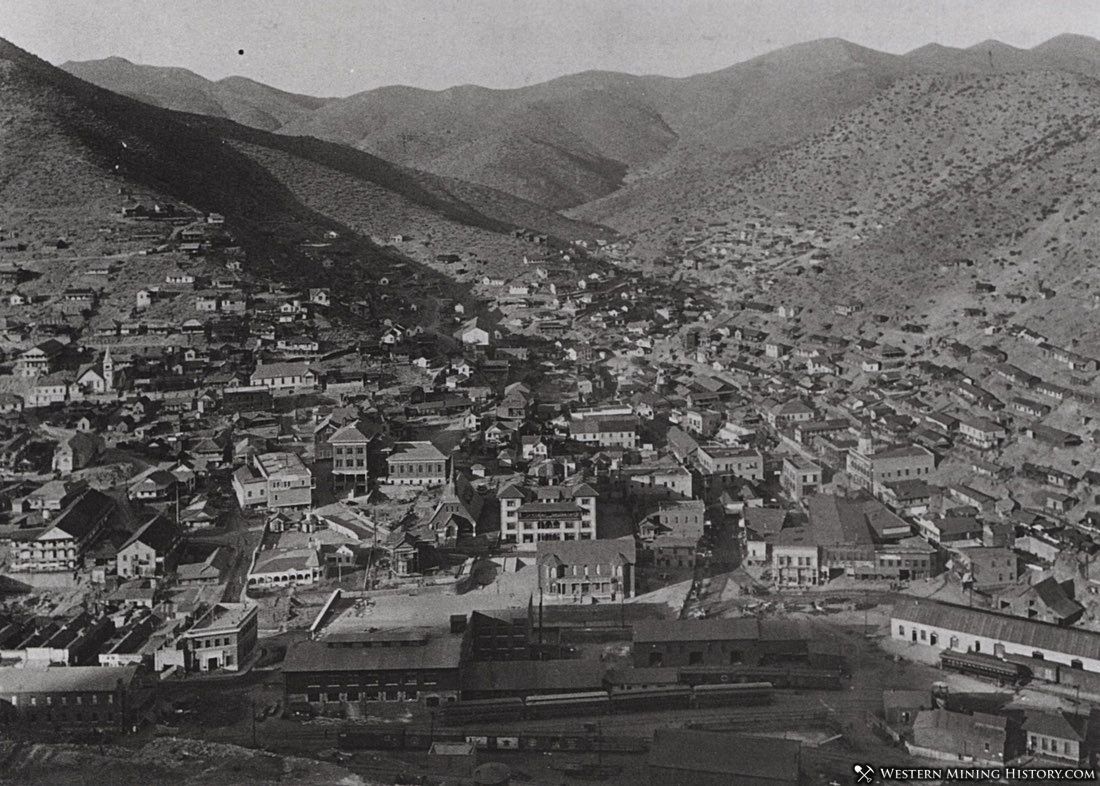

The Bisbee of the late 1870s was a camp of just a few hundred people. The town was eclipsed by its neighbor to the north, Tombstone, which grew to be a boom town with thousands of residents. Tombstone’s silver mines initially allowed for more rapid growth than Bisbee could manage, but it would not be long before copper was king in Arizona, and Bisbee would become one of the great mining cities of the West.

The Phelps Dodge Company entered the Bisbee mining scene in 1881 with the purchase of the Atlanta claim. In 1885, the company merged the Atlanta with the adjacent Copper Queen, and the resulting operation would become the second largest producer of copper in the nation during the last two decades of the 1800s, behind the Anaconda operation in Butte, Montana.

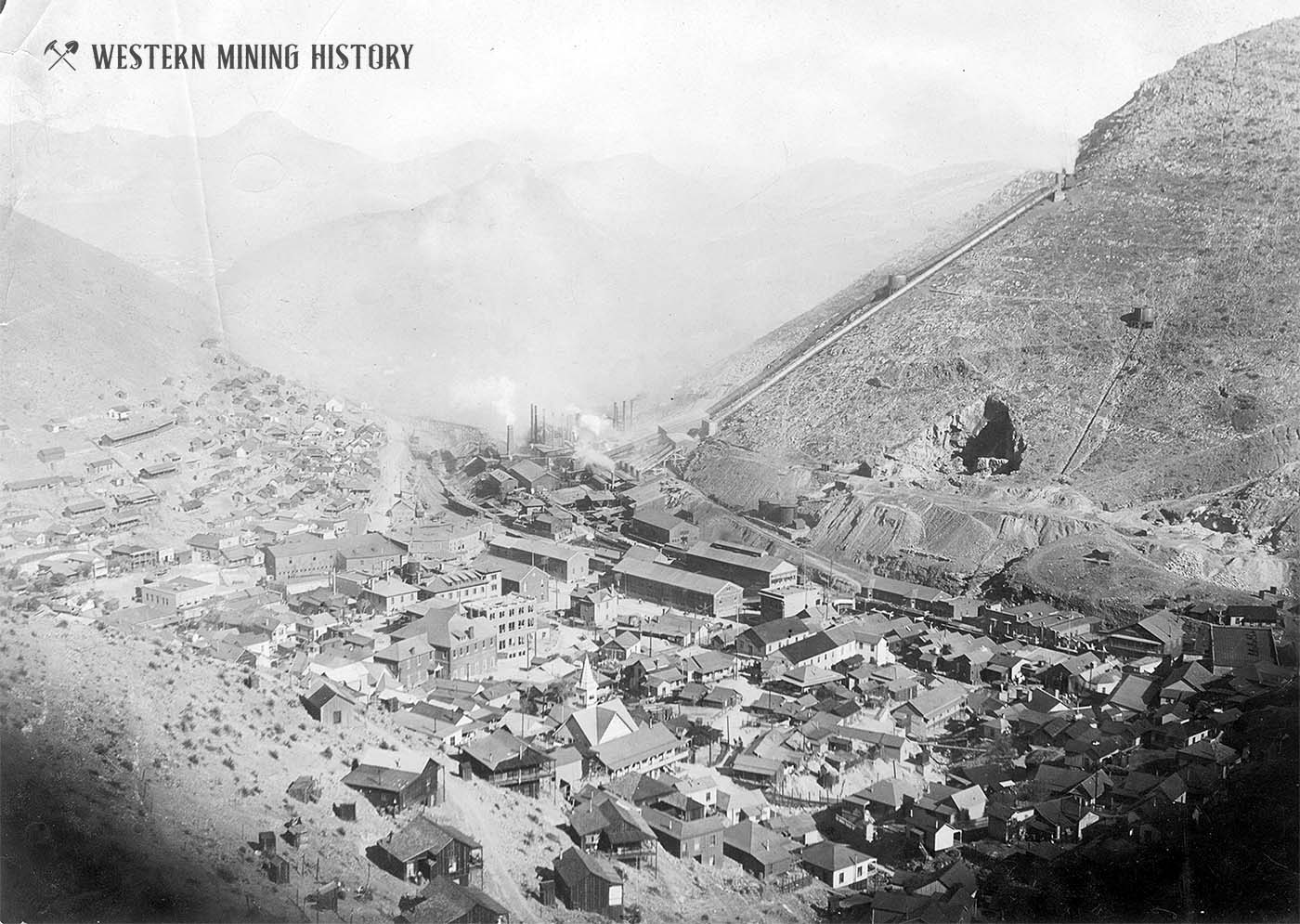

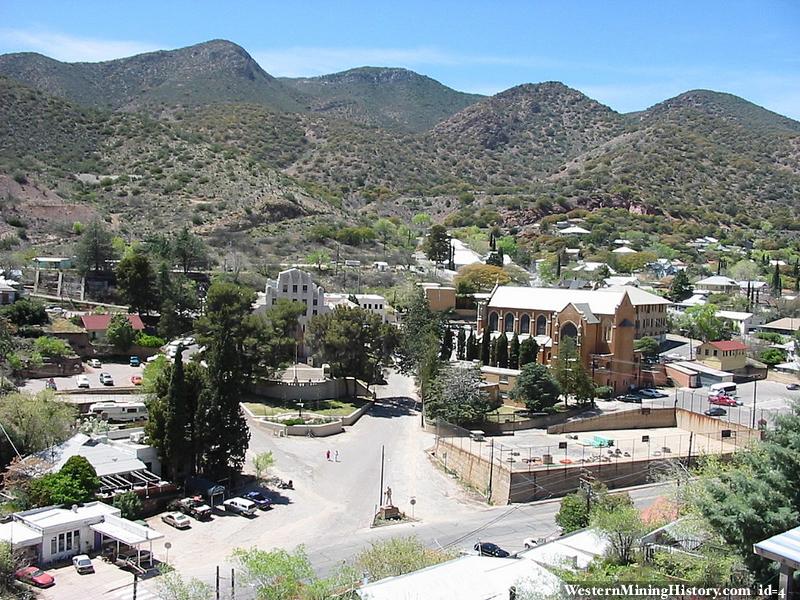

Bisbee experienced rapid growth with the success of its copper mines and the arrival of the railroad in 1889. From 1899 to 1918, the towns population grew from around 4,000 to a peak of over 25,000 residents (this figure includes all the towns in the district including Warren and Lowell). In 1902, the year that Bisbee was incorporated, the population stood at around 8,000.

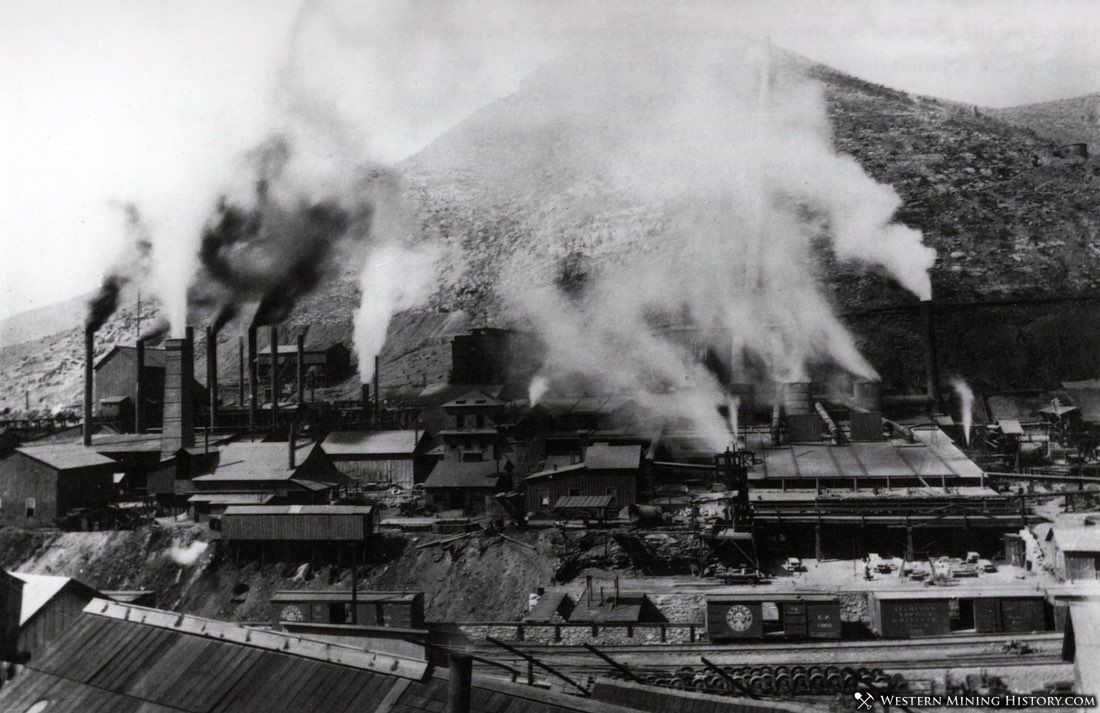

Smelting in Bisbee started in the early 1880s. The hills around the town were once covered in trees, but the thousands of cords of wood needed by the smelters each year quickly stripped the hills of trees and smelter fumes killed off much of the remaining vegetation.

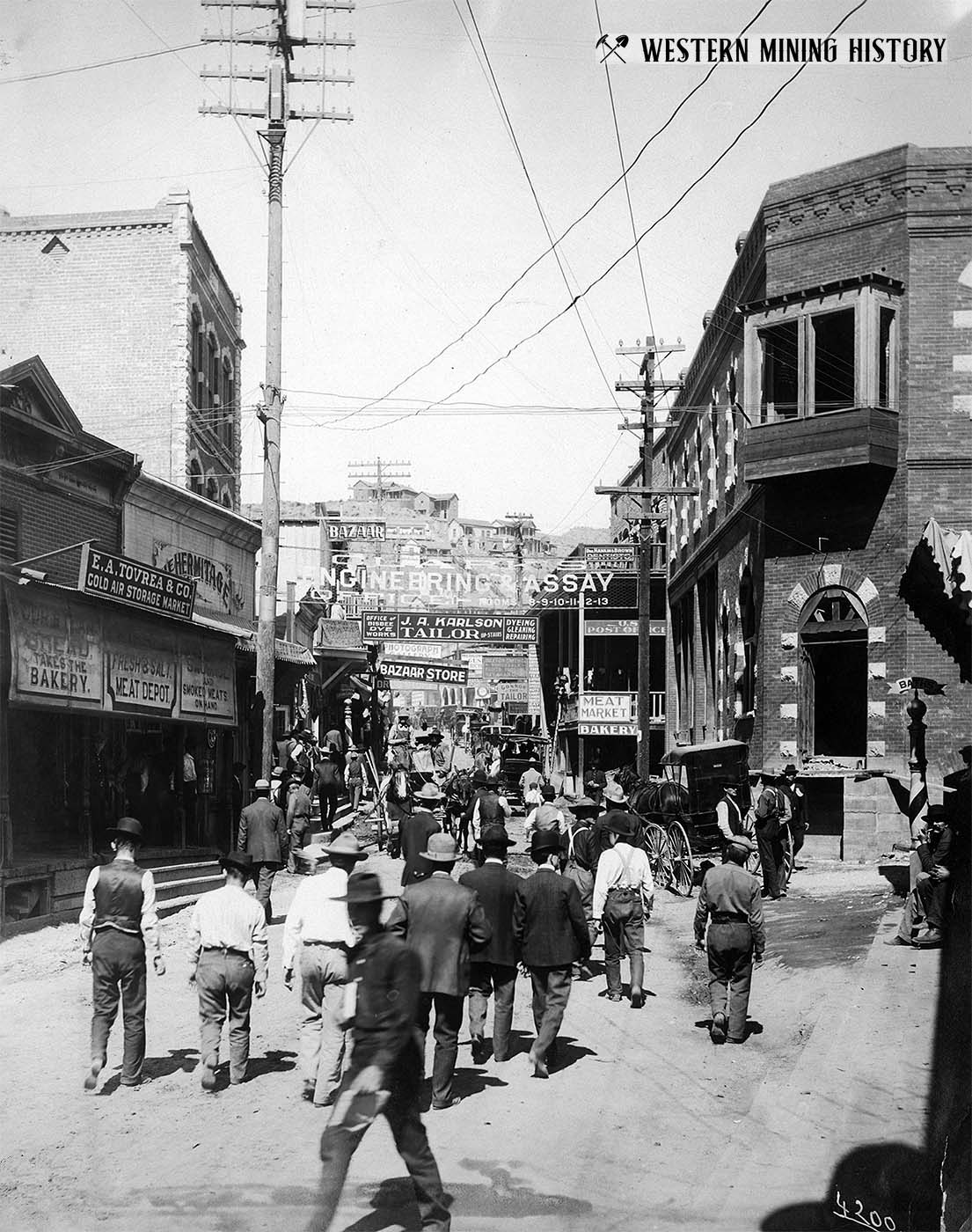

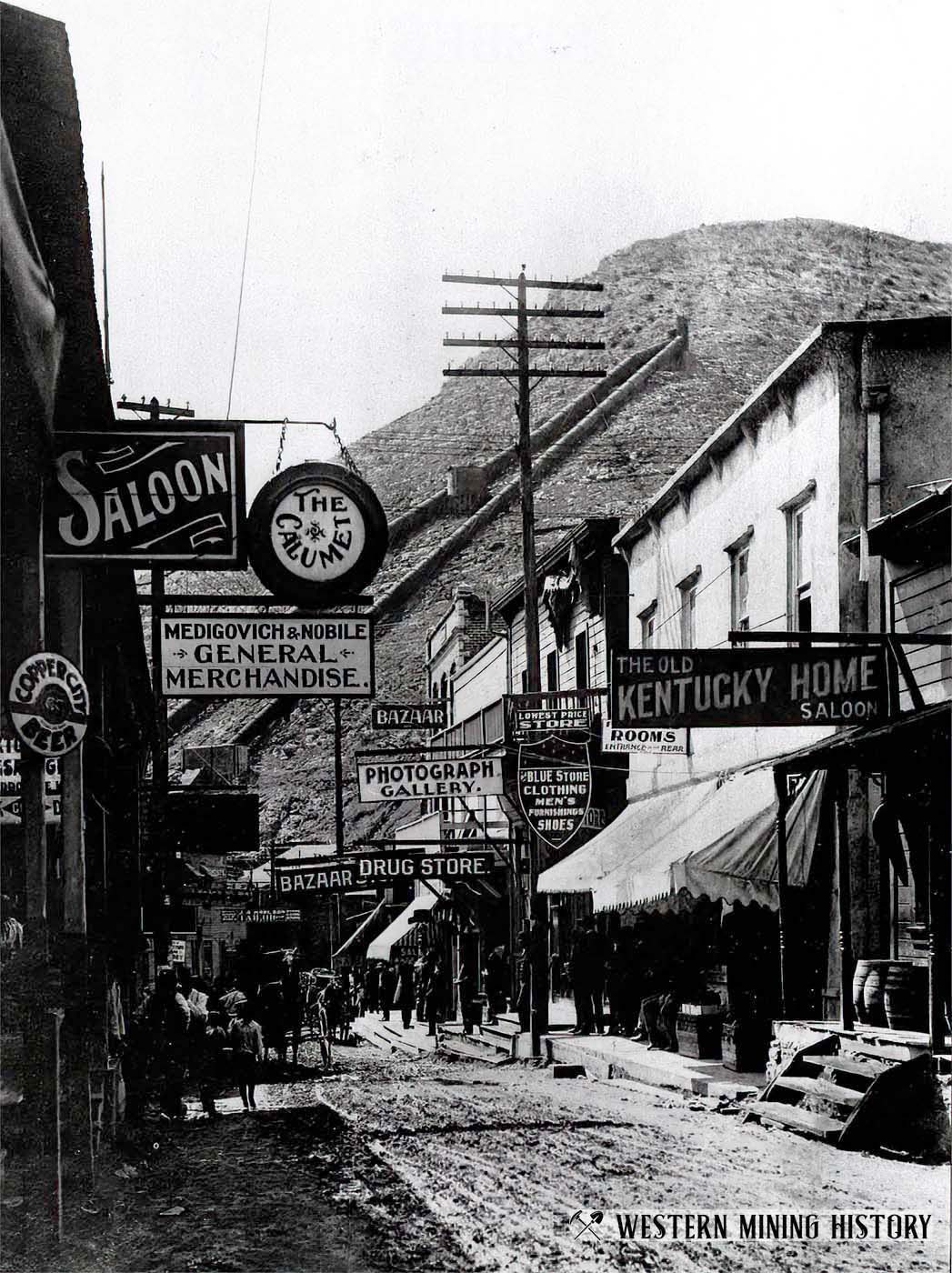

Bisbee of the 1890s was described as being a dirty and smoke filled camp. One can imagine how a frontier industrial boomtown with no regulations or public services would devolve, especially a town of thousands built in narrow canyons of the Mule Mountains.

Drunkenness and violence were common. Prior to 1900 Bisbee had up to 50 saloons as well as gambling halls and houses of prostitution. Trash was thrown in the streets and open sewage pits added stench to the already noxious air. The carcasses of animals lay in the streets.

With little vegetation to slow the cascade of water during the summer monsoon season, disastrous floods became a common occurrence.

At the turn of the century, demand for copper continued to rise and Bisbee continued to grow. The frontier town would soon transition into one of the great industrial cities of the West, and conditions in the town would improve accordingly.

Bisbee Enters the 20th Century as a Modern City

While the Bisbee of the late 1800s was described as a dirty and raucous town, after 1900 many changes took place that improved conditions in the town.

By 1905 two more copper companies were operating in Bisbee alongside Phelps Dodge; Calumet & Arizona and Shattuck-Arizona companies. Copper was now big business, and the city of Bisbee needed upgrades to accommodate the influx of miners and their families.

Flood control measures were implemented that helped mitigate (bot not eliminate entirely) the danger of regular flooding. Phelps Dodge moved its massive smelter from Bisbee to Douglas, drastically improving air quality.

A sewer system was built in 1908, eliminating the problem of the open waste pits. A pipeline was built to bring fresh water from springs six miles away, replacing the need to haul water to town by burro.

Many of the hastily built ramshackle buildings from the 1880s and 1890s were being replaced by substantial buildings built of brick and stone. The luxurious seventy-two room Copper Queen Hotel was completed in 1902 and still operates today.

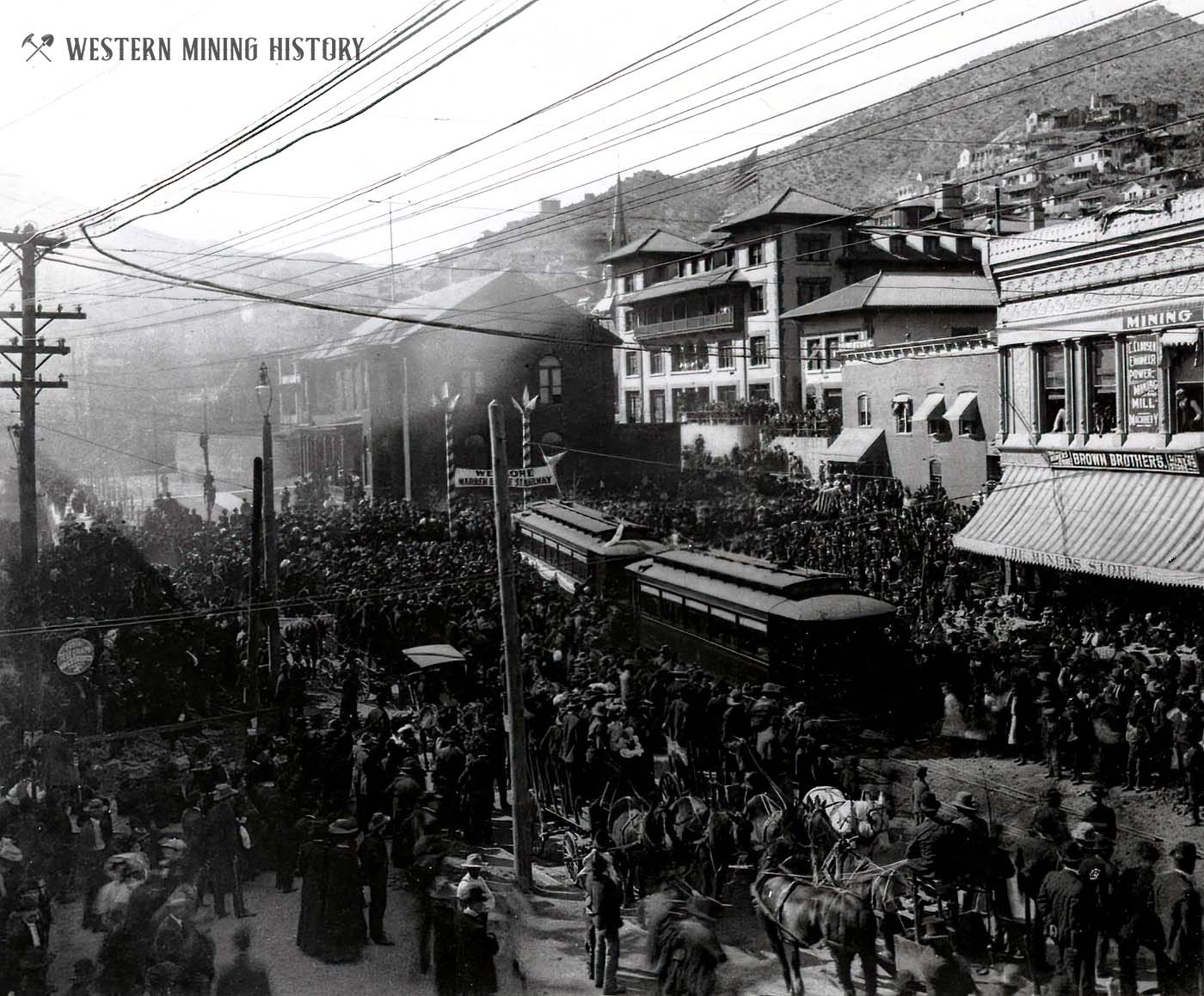

Electrical and telephone service were expanded to most parts of town. In 1908, a streetcar line was built between Bisbee and the satellite town of Warren.

As more families arrived in Bisbee, the desire and will to clean up the town only increased. The first ordinance passed after the city was incorporated in 1902 was to ban women from saloons. By 1910 gambling and prostitution had been outlawed.

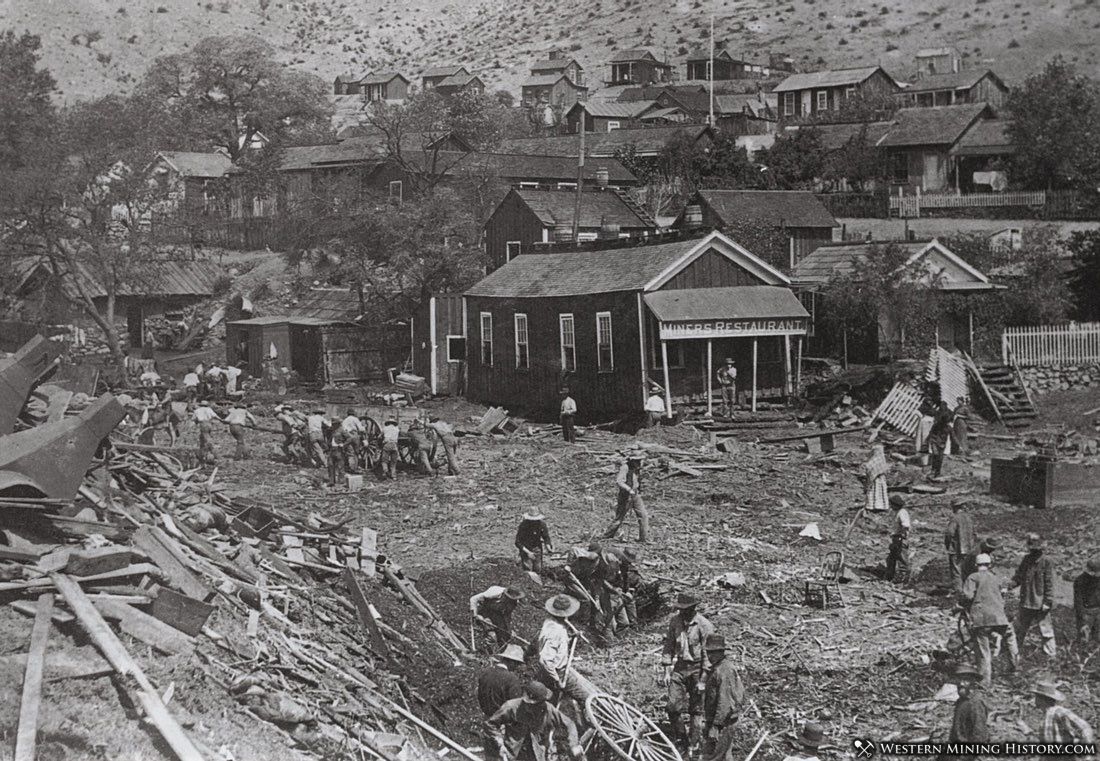

Bisbee experienced a devastating setback with the great fire of 1908, which left hundreds homeless and burned half of the commercial district. However, with the great mines of Bisbee still employing thousands of men, the city was quickly rebuilt.

With the goal of processing lower grade ore profitably, Phelps Dodge began open-pit mining. Sacramento Hill, an iconic landmark at Bisbee, was first blasted in 1917 and would become the Sacramento Pit, one of the first open-pit mines in the United States.

The Sacramento Pit would be excavated until 1929 when the operation ended. In 1950 a second, larger pit was started that would become known as the Lavender Pit. The Lavender Pit operation lasted until 1974. The pit is now a major landmark just outside of the town of Bisbee.

The Bisbee Deportation of 1917

The onset of World War I caused a dramatic rise in the price of copper. While increased commodity prices were generally seen as a positive development in western mining towns, the reality was that miners were expected to work harder and sometimes longer hours, often for the same pay.

The influx of new miners to a booming mining town would drive up the cost of living, further exacerbating the grievances of the thousands of miners working in the district.

In May of 1917, the miner’s unions, one of which was affiliated with the radical Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), presented a list of demands to the Phelps Dodge company. These demands were rejected by Phelps Dodge, and a strike was inevitable.

Around 3,000 miners began to strike on June 27. The strike was peaceable but the mine owners feared that the IWW members would start trouble. While the IWW had been responsible for violence and sabotage in other districts, less than twenty percent of the strikers at Bisbee were IWW members.

Phelps Dodge used the presence of IWW members as cause for drastic and unprecedented action against the striking miners. The company conducted a trial run of the deportation at Jerome on July 10. Sixty-seven members of the IWW were rounded up and deported by rail to Needles, California.

The deportation at Bisbee would be much greater in scope, the largest such action ever taken in the West.

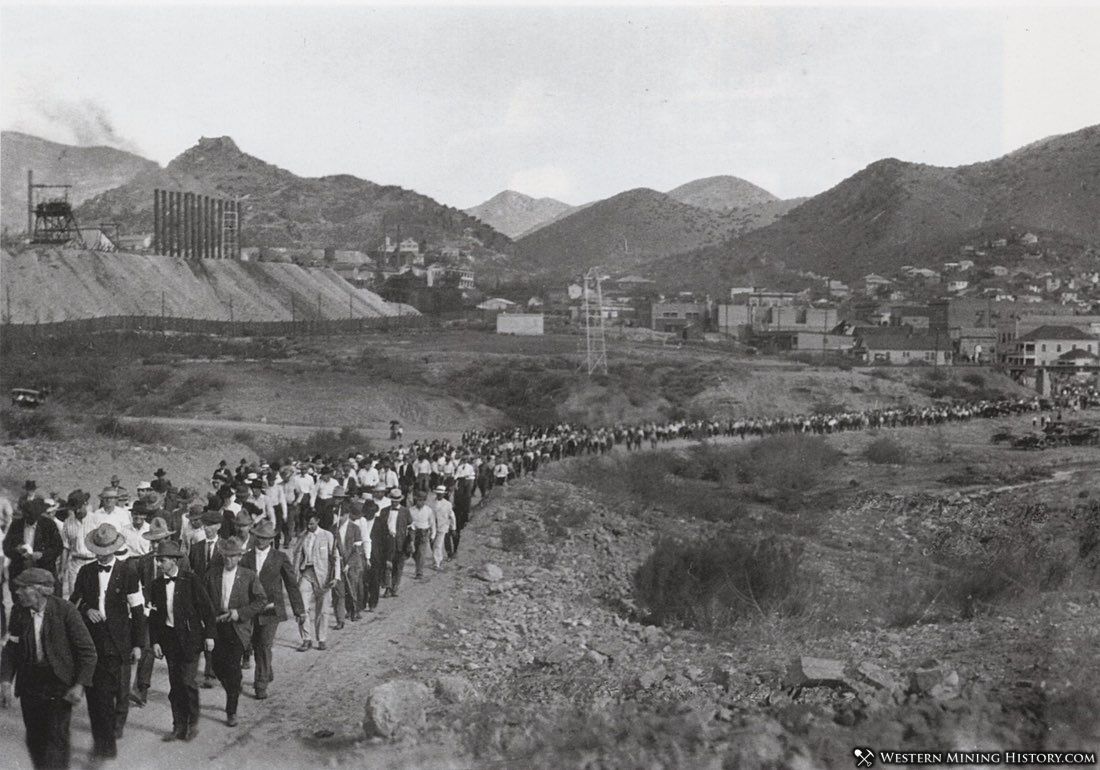

On July 12, 1917, a posse of 2,200 men led by Sheriff Wheeler dispersed through the streets of Bisbee in the early morning hours. The posse had a list of strikers and regular citizens who were thought to be sympathetic to the IWW.

Around 2,000 men were arrested, some of them local business owners. The men were marched two miles to the ballpark in Warren. The march was overseen by Sheriff Wheeler from a car outfitted with a belt-fed machine gun. Once at the ballpark the men were offered the chance to denounce the IWW, end the strike, and return to work. Around 700 men accepted this offer.

The remaining 1,286 detained men were forced by gunpoint onto 23 railroad cattle cars. The train carrying the strikers travelled east to Columbus, New Mexico where the strikers were to be unloaded. Officials in Columbus protested having the men dumped in their town, and the train turned around and travelled back to Hermanas, New Mexico, where it unloaded the men at 3:00 a.m.

During the more than twelve hours the men were on the train, much of the time in 90 degree heat, they were given little or no water and no food. With almost 1,300 penniless men stranded in the desert, New Mexico had a crisis to deal with.

The Governor of New Mexico Washington Ellsworth Lindsey contacted President Wilson and asked for assistance. Federal troops were sent to escort the deportees to Columbus where they were housed in tents for two months until September 17.

In October 1917, President Wilson appointed a commission to investigate the labor disputes in Arizona. The commission concluded "The deportation was wholly illegal and without authority in law, either State or Federal". In May of 1918, 21 executives of the Phelps Dodge company were arrested for their role in the deportation, but none were convicted. None of the deported men were allowed to return to their homes or jobs.

Bisbee’s Copper Legacy

Mining at the Lavender Pit stopped in late 1974, and for the first time in nearly a century no mining was taking place at Bisbee.

Bisbee produced around 8 billion pounds of copper over a period of almost 100 years. The mines also produced significant precious metals with 102 million ounces of silver and 2.8 million ounces of gold. Lead, zinc, and manganese were also produced in significant quantities.

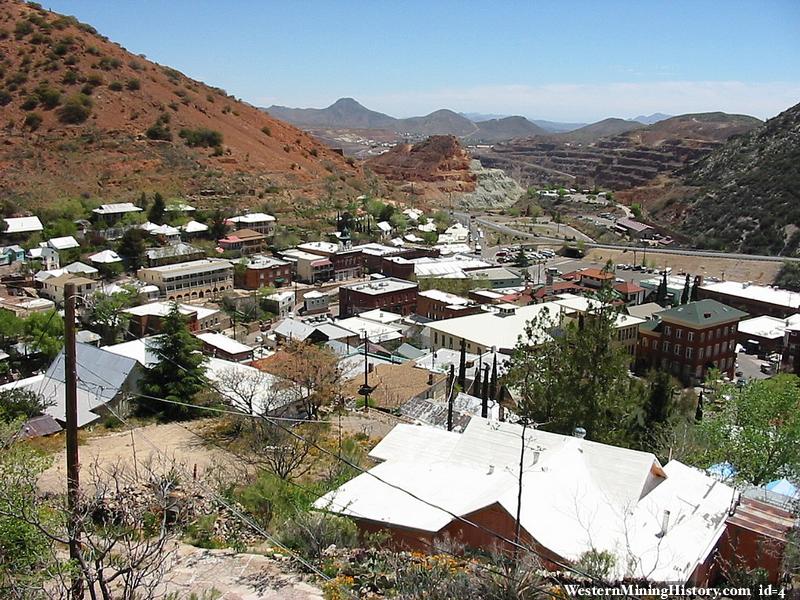

The great mines of the Warren district also left behind one of America’s most interesting and historic towns. Unlike other great copper camps in the West, Bisbee was spared complete destruction by open-pit mining. However, the town also had to survive the loss of its only industry.

Fortunately the historic homes and buildings in Bisbee attracted preservation-minded people. Actor John Wayne was a frequent visitor to the town and partnered in real estate ventures early in Bisbee’s transition from a mining economy.

Even though mining at the Lavendar Pit continued into the 1970s, open pit mining did not employ nearly as many people as the underground mines and thousands of jobs had been lost since the district’s peak years. The resulting reduction of population in the area made real estate very inexpensive, and cheap housing combined with an attractive climate and beautiful scenery attracted many artists and hippies during the 1960s and 1970s.

This repopulation kept Bisbee alive and helped preserve many of the town’s most historic structures and old miner’s homes. The town has become a popular home for retirees and a busy tourist destination. What might have become another dilapidated former mining camp has regained much of its splendor and is one of the best preserved historic mining towns in the West.

Arizona Mining Photos

View over 35 historic Arizona mining scenes at A Collection of Arizona Mining Photos.

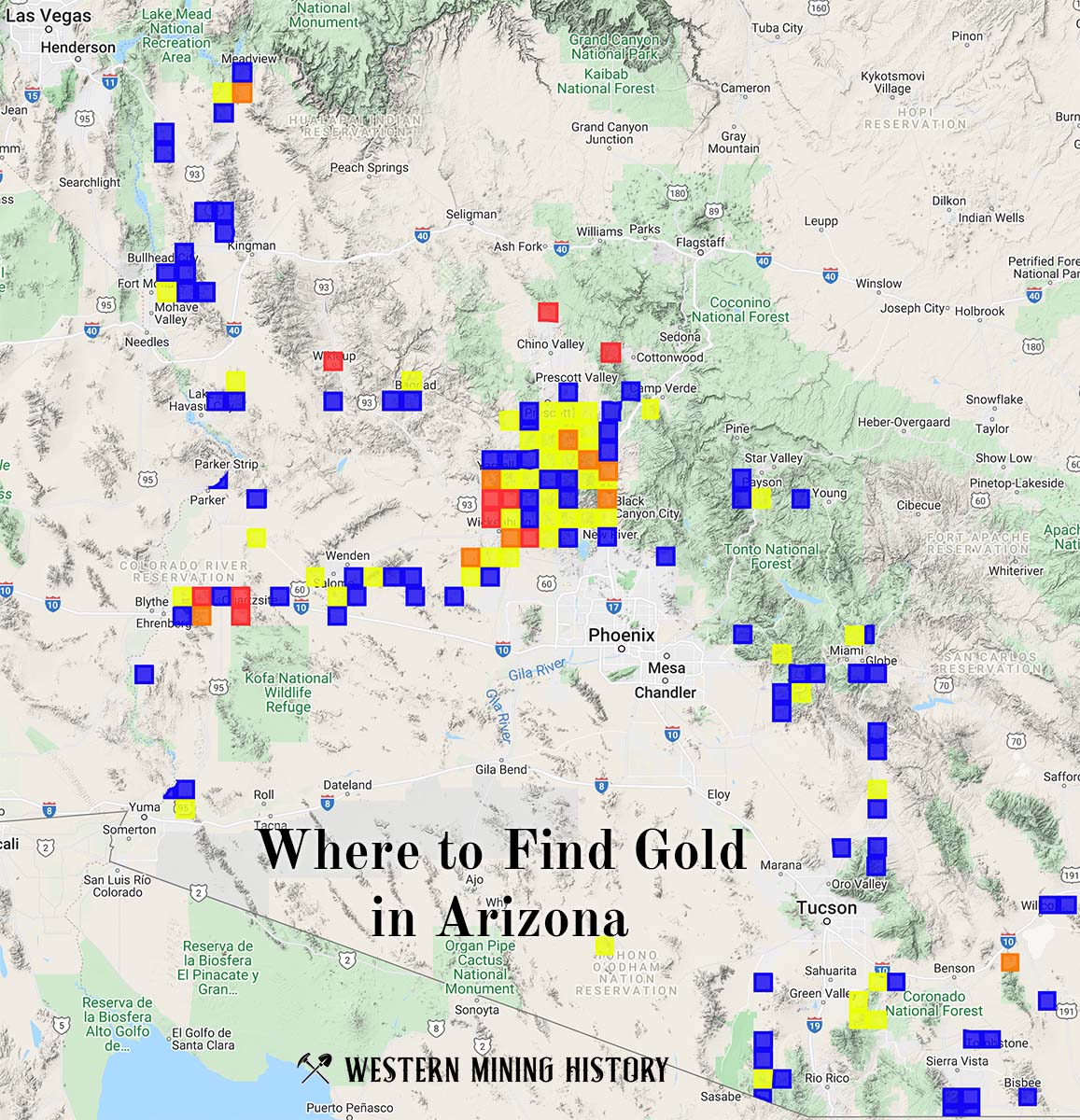

Arizona Gold

"Where to Find Gold in Arizona" looks at the density of modern placer mining claims along with historical gold mining locations and mining district descriptions to determine areas of high gold discovery potential in Arizona. Read more: Where to Find Gold in Arizona.