The Colorado Gold Rush, originally known as the Pikes Peak Gold Rush, started in 1858 and was the second largest mining excitement in United States history after the great California Gold Rush a decade earlier.

Over 100,000 people participated in this rush and were known as “Fifty-Niners”, a reference to 1859, the year the rush to Colorado peaked.

At the time of the rush, Colorado was still part of Kansas and Nebraska territory.

The Colorado Gold Rush resulted in a dramatic influx of emigrants into the Rocky Mountain Region. “Pikes Peak or Bust” was the motto of many of the emigrants, a reference to the mountain in the Front Range that guided many early prospectors westward over the Great Plains.

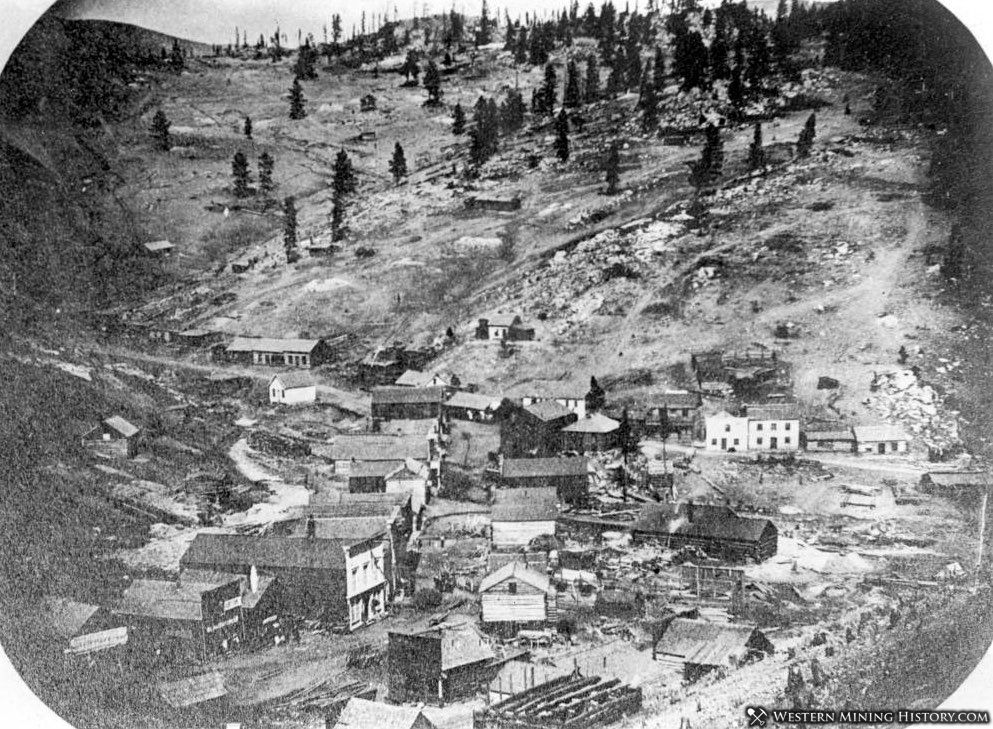

The prospectors were the first major non-native population that entered region, leading to the creation of many early towns, including Denver, Boulder, Golden, and numerous smaller mining towns, some of which are still active communities today.

As prospectors flooded the region in search of quick riches, the rapid population growth led to the creation of the Colorado Territory in 1861 and to the U.S. state of Colorado in 1876.

The initial gold discoveries were made below the confluence of Cherry Creek and the South Platte River, which is now the location of downtown Denver. Denver City was established near the gold discoveries in late 1858. There was not a lot of gold here, but news of the strike was enough to cause a buzz back east that started a full-blown gold rush the following year.

The first decade of the boom was largely concentrated along the South Platte River at the base of the mountains, the canyon of Clear Creek in the mountains west of Golden, South Park, and just over the Continental Divide in the Breckenridge area.

Gregory Gulch and Central City

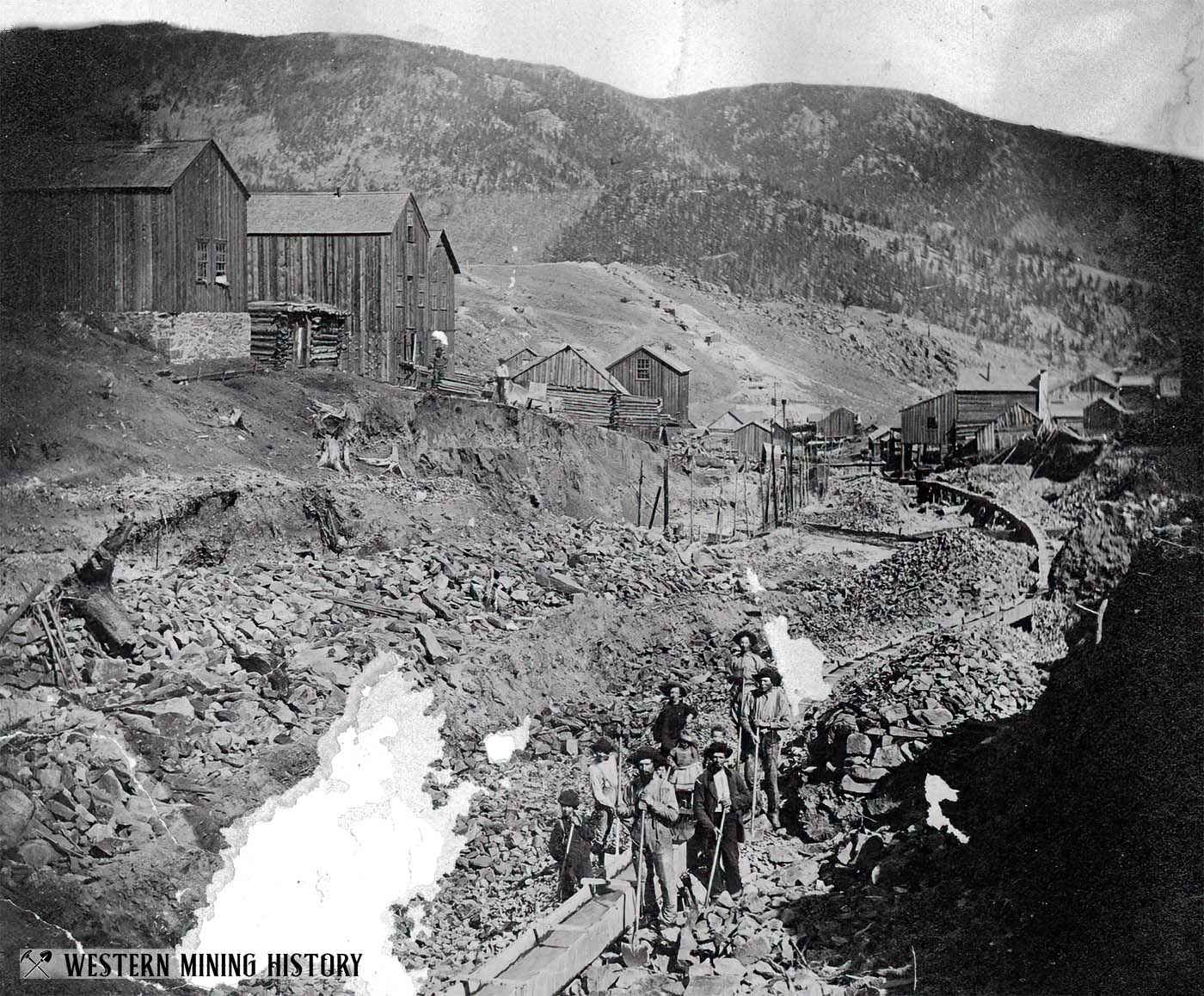

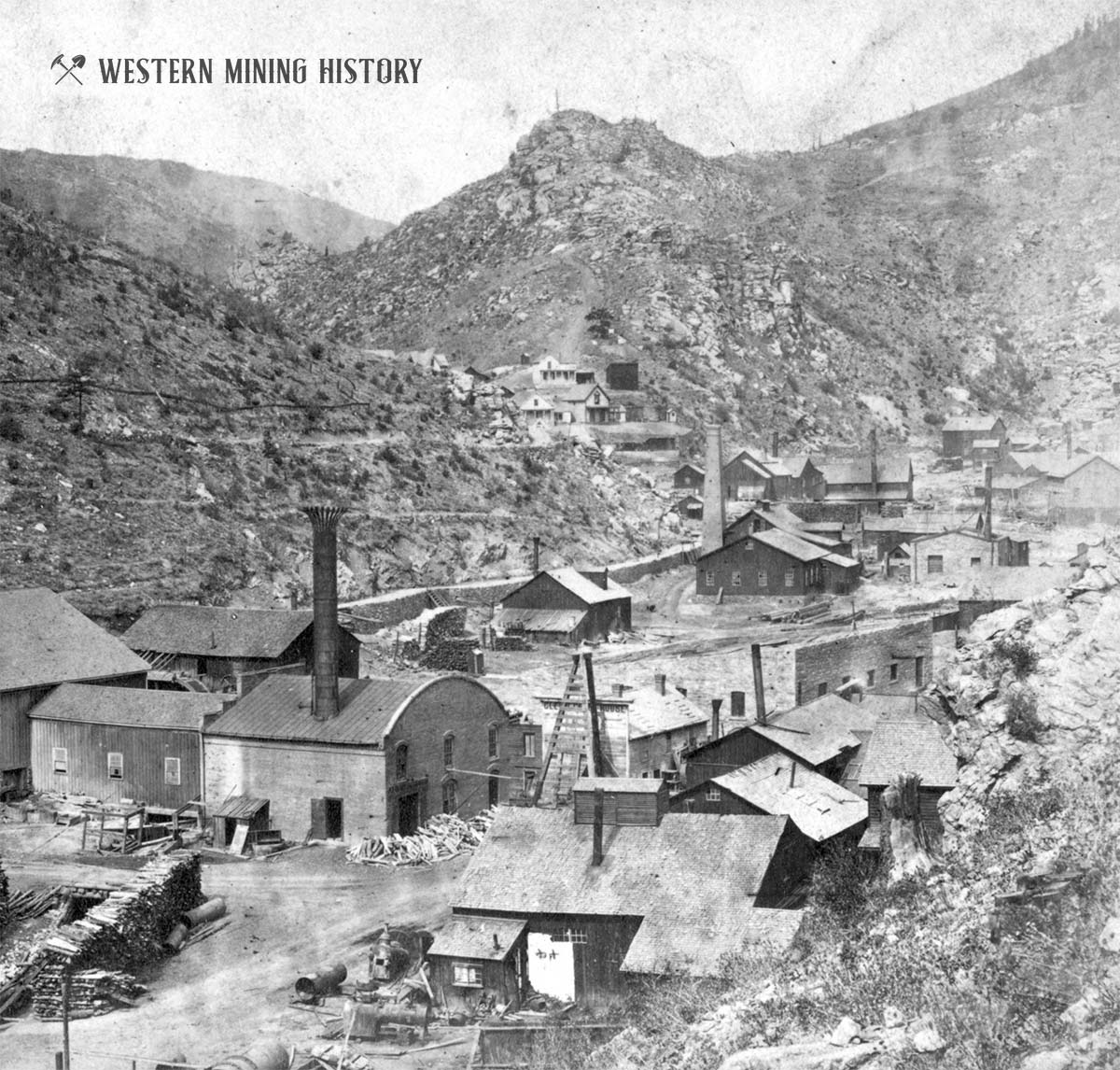

The first “bonanza” of rich gold placers was discovered by a prospecting party from Georgia led by John Gregory, at a site that was first named “Gregory Gulch”, but would soon be the site of the Central City mining district. This district became the economic center of Colorado for almost two decades, and became known as “The Richest Square Mile on Earth”.

An interesting story from the early days of the rush is that of William Greeneberry Russell, more commonly known as Green Russel. Russell was a rival of Gregory from Georgia, and was the leader of the large prospecting party that made some of the earliest gold discoveries in the Cherry Creek area in 1858.

News of Green’s discoveries made their way to Eastern newspapers, and those stories are credited as the stimulus that caused the frenzied rush to the Pikes Peak region in 1859.

Gregory, who showed up after Russell, by chance stumbled on to the rich gold placers at Gregory Gulch and became the central character in the Pike’s Peak Gold rush story. Not long after Gregory’s discovery, Russell and his party (by that time over 200 men), visited the gulch. It is said that Russell and Gregory, who had some kind of rivalry back home, did not acknowledge each other, and Russell’s party moved on in search of a new strike.

Ultimately Russell and his men did strike gold, just a few miles up the gulch from Central. The town they established was named Russell Gulch, and although it was not nearly as rich as the diggings discovered by Gregory, it did become the center of a district that was active for decades.

Early Gold Rush Towns

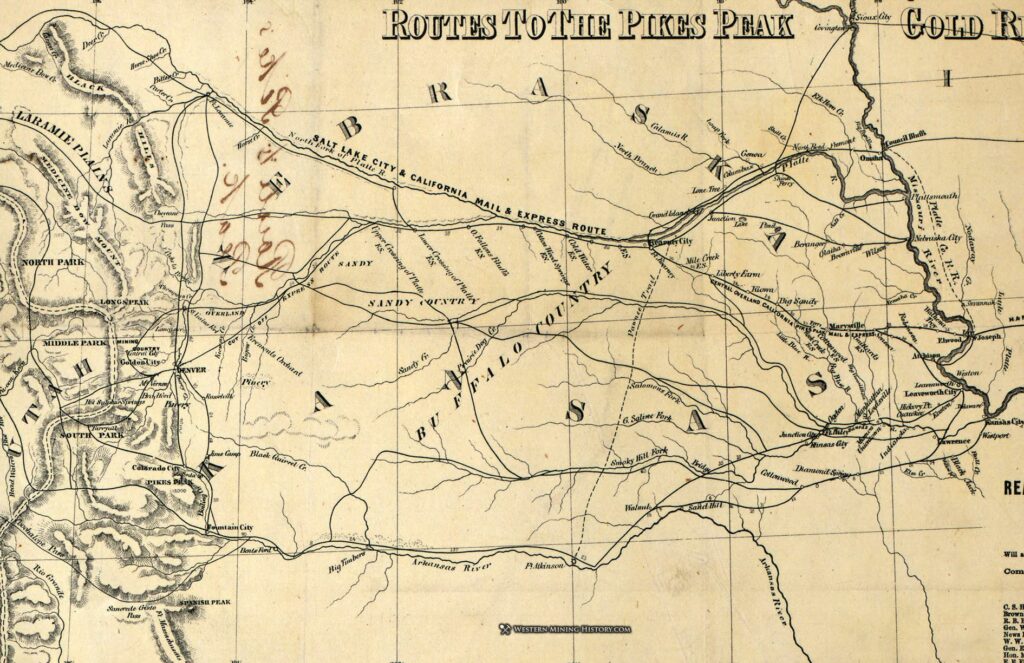

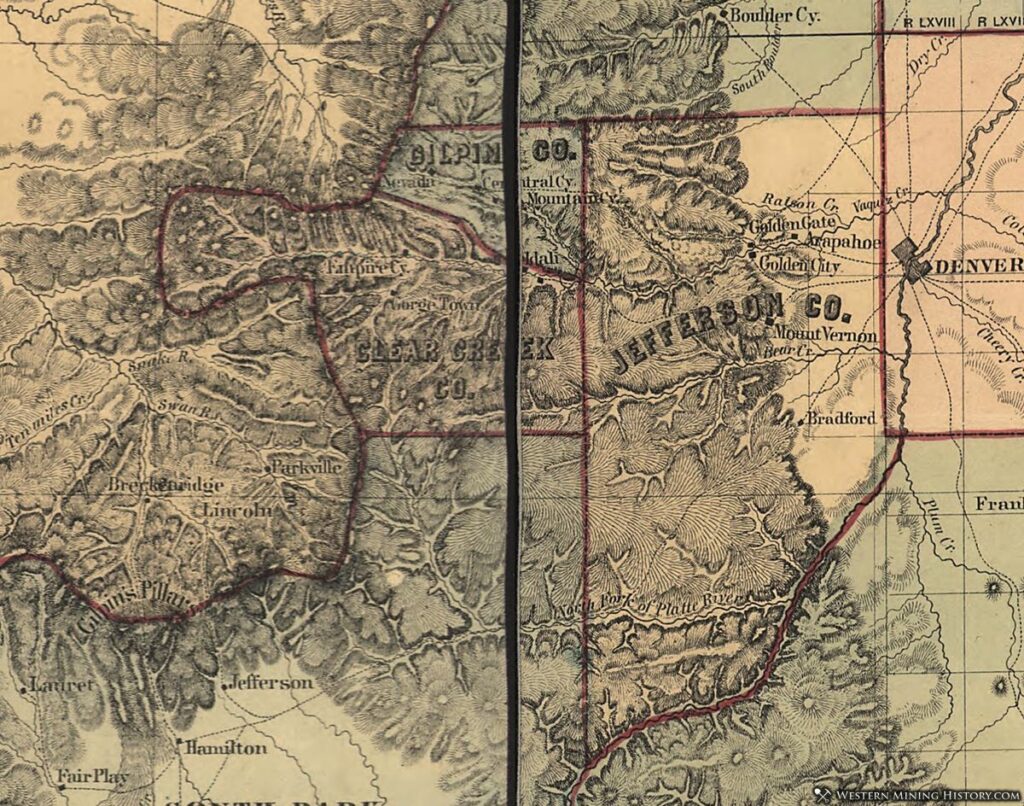

Many towns were settled during the Colorado Gold Rush – some have grown into important cities, but many became ghost towns long ago. The following map was published in 1862 and shows many of Colorado’s oldest towns and cities.

Golden City (now Golden) was an important supply center for the mines and camps of early gold rush Colorado. It was the first territorial capital from 1860 until 1867 when it was moved 12 miles east to Denver.

Denver is now the capital of Colorado and the state’s largest city. In 1859 however it was just a supply stop on the way to the gold mines. A November 1859 newspaper stated “Denver City is an unimportant place, being a sort of fitting out station for Pike’s Peak”.

Boulder City (now Boulder) was settled in 1858 as a supply center to the mines. In 1861, the Colorado General Assembly passed legislation to locate the University of Colorado in Boulder, a move that ensured Boulder would outlast the mines that it served in the early years of the Gold Rush. Today Boulder is a significant city.

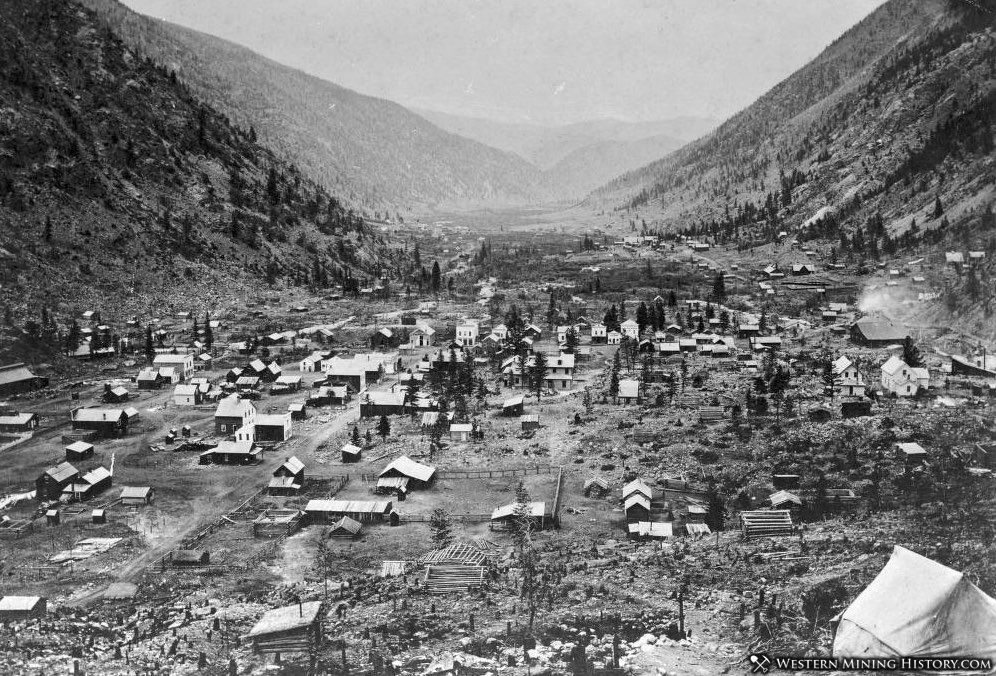

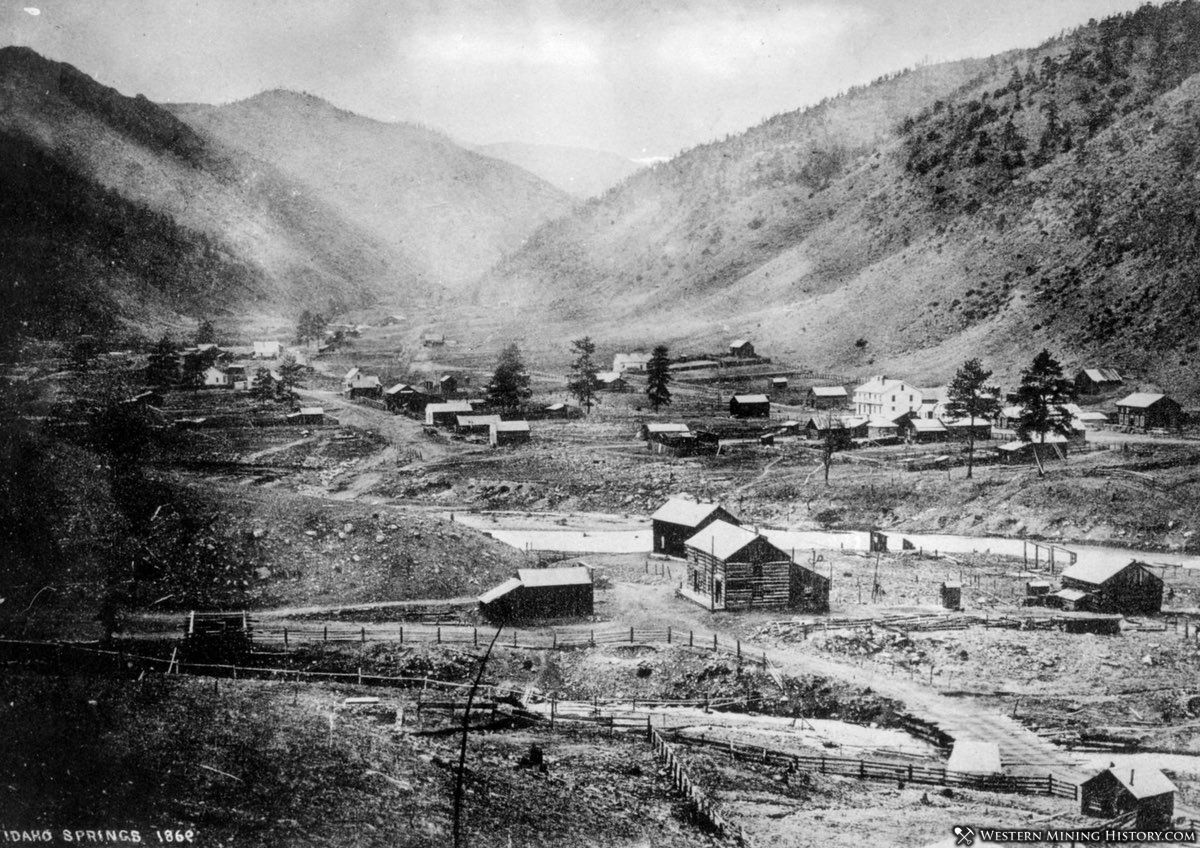

Other towns on the map did not become major cities, but remain viable communities today. Central City, Idaho (Idaho Springs), and Georgetown were important centers of mining as far back as the early 1860s, and all remain today as some of the best examples of historic 1800s mining towns in the entire West.

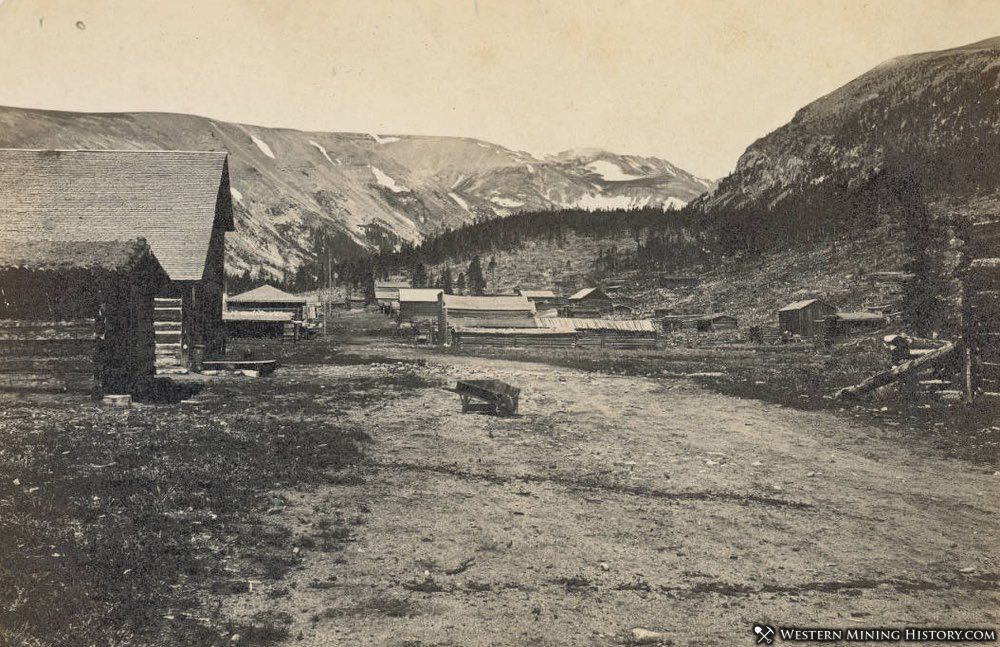

The map also reveals how far the prospectors pushed into the mountains early in the rush. The town of Fairplay was established in 1859 among rich placer mines at almost 10,000 feet in elevation. Miners pushed on that same year, crossing the Continental Divide and founding the town of Breckenridge, which became the state’s most important gold placer district.

Some of the towns on the map became ghost towns just a few years after they were founded.

Lauret (also known as Buckskin Joe), was the Park County seat from 1861 to 1866. Horace Tabor, who would go on to be one of the State’s richest mine owners at Leadville, operated a store and was the postmaster here. Buckskin Joe faded in the mid-1860s as the placer gold ran out, and soon became a ghost town.

Other early towns of importance that became ghost towns long ago include Parkville, Lincoln, Hamilton, and Jefferson. In the case of Hamilton and Jefferson, it seems that these early gold camps only lasted a short time, and later new mining camps emerged at different locations using the same names, only to become ghost towns for a second time.

Gold Rush to Mining Empire

The rush to the Colorado gold fields was prompted by the relatively easy to mine placer gold deposits found in various gulches and streams of the eastern part of the state. Most of these placer mines were exhausted in just a few years.

During the California Gold Rush, when the placer diggings played out, miners moved on to newly discovered gold fields, adapted new mining techniques like hydraulic mining, or located the source of the gold and transitioned to lode mining. These options were not easily attainable in Colorado.

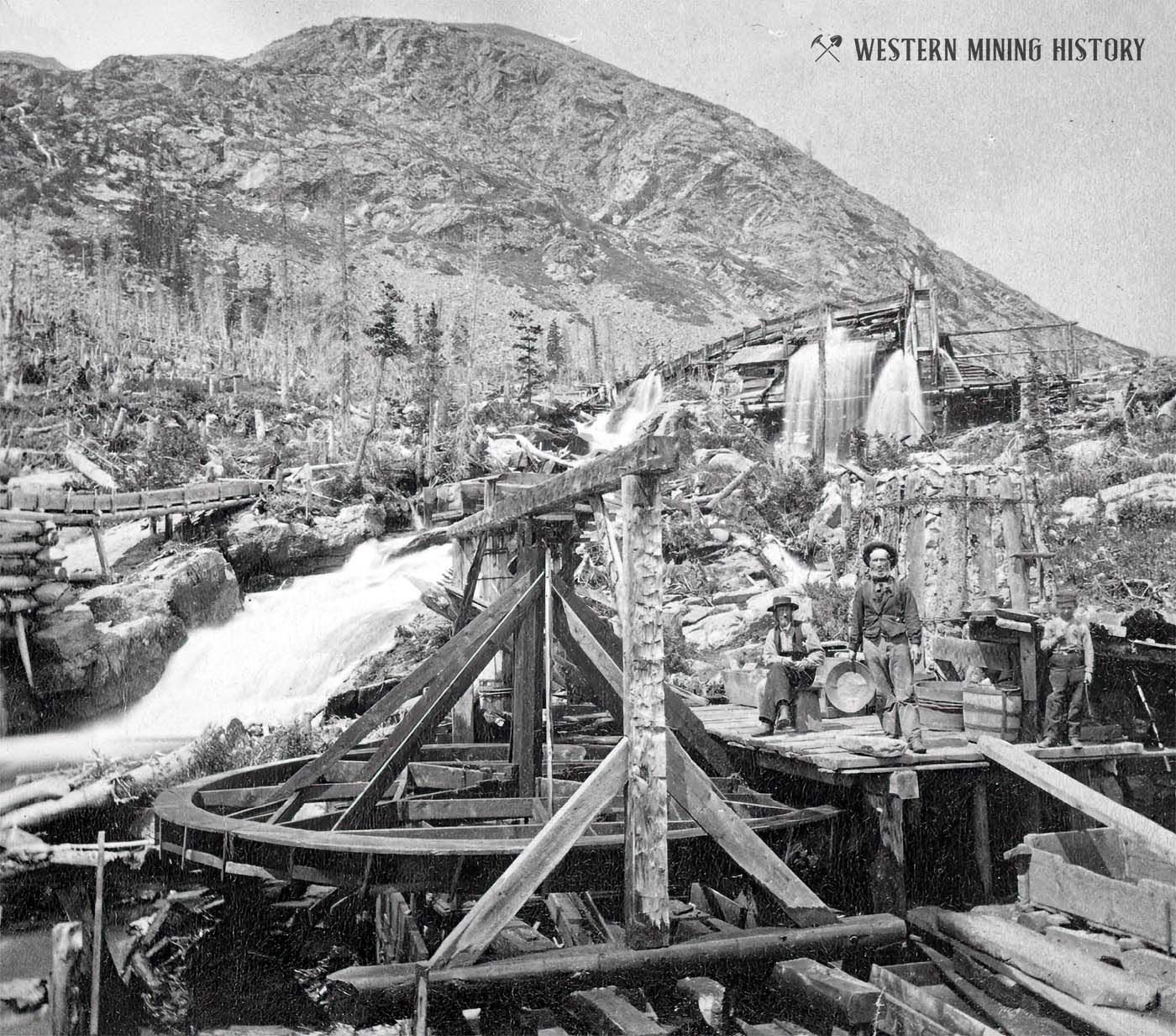

Colorado’s extremely difficult terrain and harsh winter weather made the search for new gold deposits challenging in the early years. Although hydraulic mining was practiced in the state, it was nowhere near the scale that was seen in the gold fields of California.

What Colorado did have was extensive and rich lode (hard rock) ore deposits, but most of the ore was not the easily processed “free milling” gold ore that was common in California mines.

By the mid 1860s, the Colorado mining industry had entered a depression. What was needed were scientific breakthroughs in ore processing techniques, and the capital to implement those breakthroughs in the form of mills and smelters. Capital was also needed to solve the state’s difficult transportation challenges, and to open new mining areas deep in the Rocky Mountains.

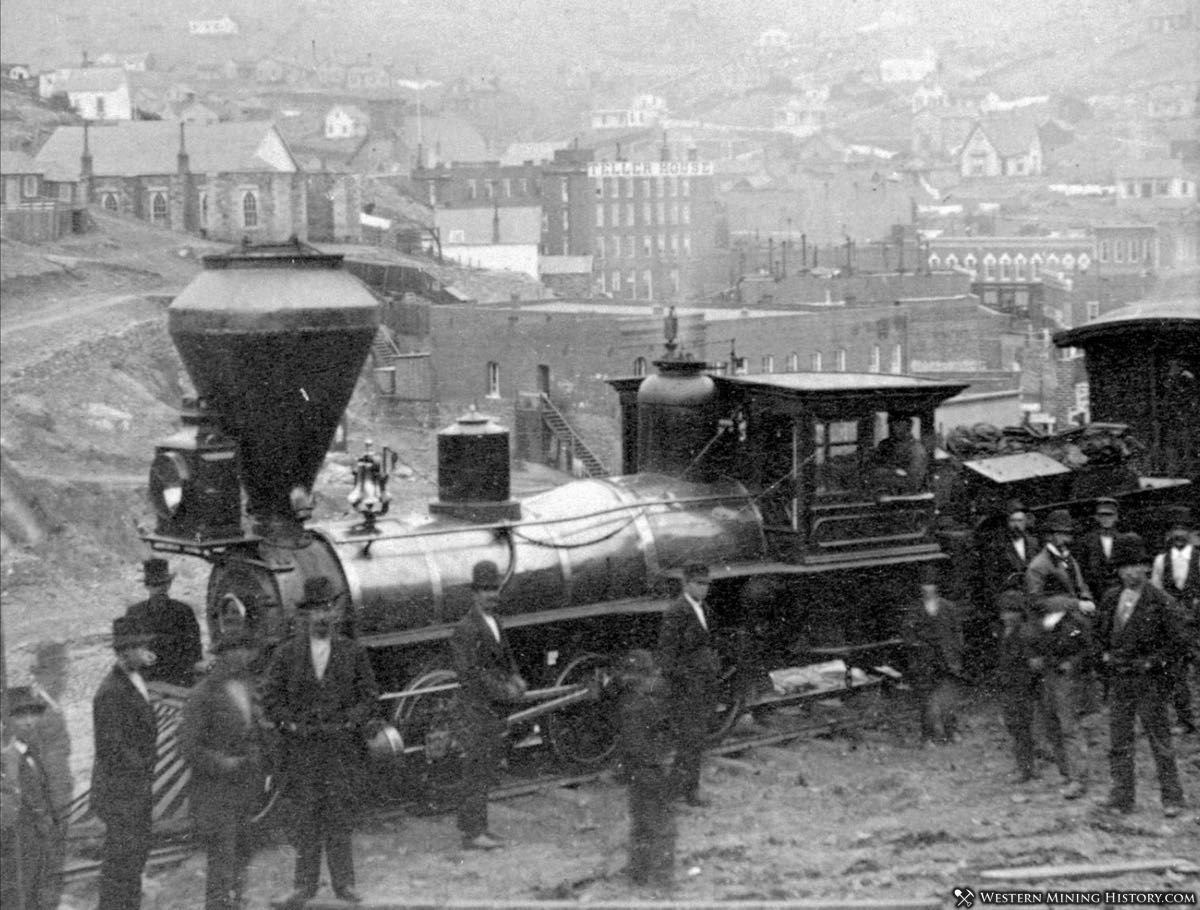

The end of the Civil War in 1865 resulted in eastern investors turning their attention to the potential of the Colorado mines. In 1869, just over a decade after the initial Gold Rush, the Denver Pacific railroad arrived in Denver, and within a decade railroads were serving all the state’s important mining districts.

By the 1870s Colorado’s Gold Rush days were over. However, capital investments, improvements in mining technology, and the arrival of the railroad greatly stimulated lode mining, starting an important new chapter in the state’s history.

Colorado Mining Photos

More of Colorado’s best historic mining photos: Incredible Photos of Colorado Mining Scenes.